Folk artist Courtney Hartman is bringing it all back home in Glade, an introspective new album that’s named for the street that runs by the eight-acre farm where she grew up in Loveland, Colorado. As a former member of the roots band Della Mae and a duet partner of Robert Ellis and Taylor Ashton, Hartman is often a willing collaborator. Yet Glade found her working primarily in isolation, living in a trailer and later a barn to rediscover the spark of songwriting.

Now married and residing in Wisconsin, Hartman tells BGS about the process of crafting these new songs, her childhood immersion in bluegrass and the experience of recharging her creativity.

BGS: When I was listening to “Bright at My Back,” the first track on Glade, I noticed the recurring phrase of “I will be returning.” That seems like a good place to start in talking about this album. Can you describe what was going on in your life as this album was starting to take shape?

Hartman: Right around that time, I was in a season just after deciding to leave New York. I had been on the East Coast for about 10 years and felt a real draw to clean the slate and make some space for new things. I didn’t know what that was yet, but I knew that I needed to take some steps and make some clearing, so I left New York and the band that I’d been in for about seven years. I moved back to Colorado to live on the property where I grew up. I still had a couple of siblings there and my dad was there. I’d been away for about 10 years.

I needed to also do a bit of a reset, musically. I needed to find some new joy or new healing in what I was playing or creating. It felt like I had lost some of that over some time. I was at a point where I was willing to let it go if it couldn’t be those things, because it didn’t feel right to keep making music or performing if it wasn’t healing in some way. In creating work, in some way, we are putting it out there and asking to be heard, right? If we didn’t put it out, we wouldn’t be asking that question. So, when I started writing this one, that was right at the cusp of that changing and slowly beginning to write again.

When you went back to Colorado, were you living in the house you grew up in?

When I first went out, my sister had spent a summer rebuilding a camper and she was going to live in it and play music. Through some unexpected circumstances, she ended up with three beautiful foster children. So, she didn’t live in the camper. I ended up moving into the camper in the yard on the property and was present for those early months with those kids. I lived in that camper for a year or so, until it got too cold, and then eventually moved into one of the barns on the property. That was a living space, but it needed a lot of work, so I worked on that for a year and a half. I was there for about three years.

What did that work entail?

Some gutting of the downstairs, and with the help of some friends, moving some beams to open up space. Pretty basic building things, but to me they were very complex because I’ve never done them. (laughs) They were very complex and slow. I think in a similar way, when I knew I needed to return to Colorado and open up some space, I didn’t know why. Similarly, with the barn, I didn’t exactly know why I was preparing that space. I just knew I needed to do that. So, I did it.

I was listening to “Bright at My Back” and “Moontalk” back-to-back, and they both have that nocturnal imagery. Were you inspired by the nighttime?

Yeah. I haven’t drawn that parallel before, but I’m remembering right when I moved back that I was outside at night a lot. I remember being so comforted by seeing the sky, because being in the city, you didn’t have that. So, that felt like a comfort of home, being able to look up and experience the stars and the moon changing. And I wasn’t traveling, so there was something about being in one place and watching slow changes happen that also felt grounding.

“Wandering,” to me, feels like a love song. What was on your mind as you were writing it?

It felt like… Oh God, this is going to sound dorky, it felt like an all-encompassing love song. I felt like I was able to accept love from my family at that point for who I was, even though I was at a low place and a very humbling place. And maybe accept love from myself. But alongside that — looking back I can see now — I had met my now-husband just weeks prior. Just a very brief meeting at a festival and we had been talking. So that certainly played in, but it wasn’t a thing at that point. It was more like a just a broader internal opening, I think.

What were some of the formative albums or artists that guided you to this point?

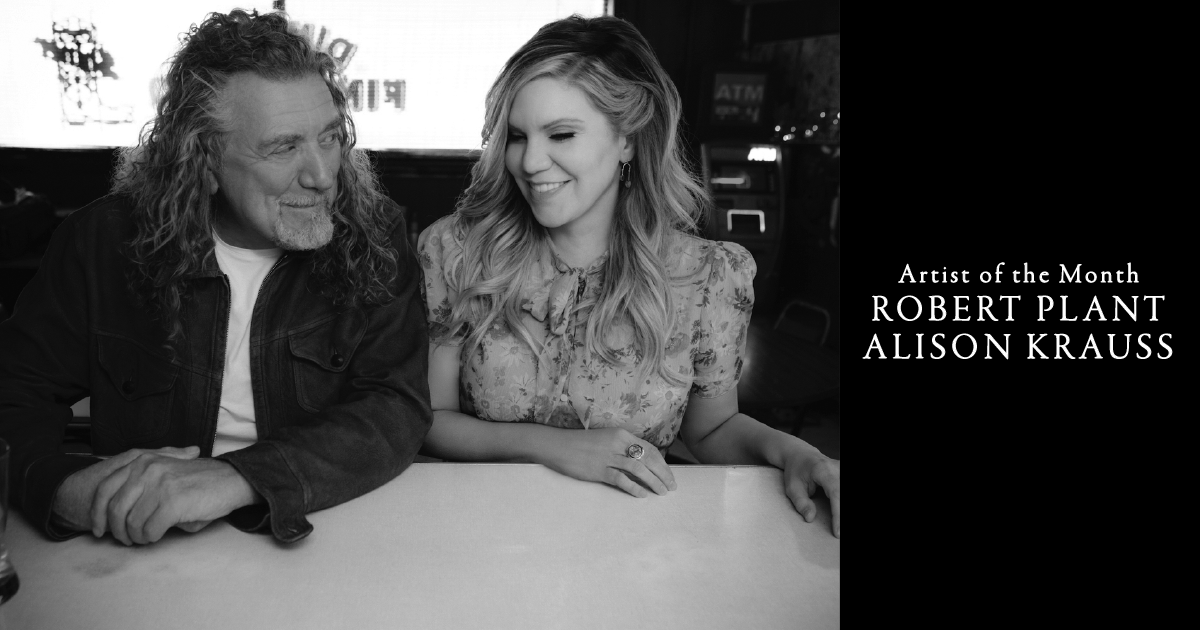

There was a Rounder Records compilation with Alison Krauss on the cover. I think she was probably 8 years old or so. My parents got that CD for me and a Yanni CD for me. I was 6 and I think I lost the Yanni CD pretty quickly, but I wore that other album out. It was pretty bluegrass, which was my background. Alison Krauss and Laurie Lewis were both on that. They were very influential. And as I got into that world, I think the singing of Tony Rice was a huge influence, besides his guitar playing obviously.

Did you get interested in bluegrass at some point, or was it just always there?

That was woven into me. My parents somehow got into it and I think they were really drawn into the familial piece of that community. They saw other families that were playing music together and I don’t know if they saw something there that they didn’t have in their childhood. I had grandparents who played music. My grandma played piano in the church, my other grandpa was a classical violinist. But they didn’t play much in their later years.

You know, the bluegrass festival is very friendly to the family unit, as far as places to go and places for kids to run around. My dad was just so patient. I wanted to run around and play in jams until one or two in the morning as a 12-year-old. And he would tag along with me. He was so kind and diligent in taking us to lessons. That was a lot to give. And it was something we could do together and not be off at soccer practice, or this or that, and be separate. … I grew up with nine siblings so there was a sort of limiting factor. We had to do things that we could do together, or at least the majority could do together.

As I was reading these liner notes, I saw that you are playing a lot of instruments on this record – guitar, bass, violin, and so on. Does that versatility come naturally to you?

Again, that was something that was woven in. I started on violin as my first instrument. My older sisters started playing when they were 12 and I was about 3 at the time. So, I started playing when I was 3, doing Suzuki. I played violin for a lot of years and that morphed into fiddle, then mandolin and guitar. My mom had a guitar. It wasn’t a forbidden instrument, but it wasn’t the instrument I was told to practice, so I inevitably got really into it.

There was a piano at the house, and all these strange instruments Dad would find on eBay. He loved buying instruments at auctions. One of the instruments he had around the house was a waterphone, which ended up on the record a good bit because it’s still at the house. And part of the playing a lot of things on this album is just the necessity of wanting a sound and being the only one working on it, so I had to figure out how to do it. I’m not a bass player by any means.

Did you just know the basics of the bass?

Enough. (laughs) I know when I play something, and it doesn’t work. And then it’s just finding something that does. It’s close enough to guitar, but with every new thing I was doing, it made me appreciate and value the people who do it really well. I value that in a different way now.

When you do listen to this record all the way through now, what goes through your mind?

I listened to the test pressing of the vinyl, which was last time I listened all the way through it. When I listen to it, in some ways it’s like depiction of a very specific time and season, and I’m so grateful for that. And of a place that’s very dear to me. Also, as much as it is that, I can hear all the learning that I have left to do. So, I’m content with it. I’m excited, too. It felt like carrying this thing for however many years, then setting it down. My arms are open again for whatever’s next, whatever that may be.

Photo Credit: Jo Babb