It all began way back, nearly seventy years ago in Memphis, Tennessee, when an almost unremarkable thing happened: A record store opened its doors.

That a record store might exist in the home of the blues in 1957 was itself no remarkable thing. But this store, Satellite Records, was quite literally a sister operation to the recording studio next door. Satellite’s owner, Estelle Axton, was the older sister of the studio’s founder, Jim Stewart.

Stewart was a fiddler with a passion for country music. Long before the dominance of indie labels, Stewart had the idea to start his own studio and label, to get his music out to the masses. As luck would have it, his original country songs were… just fine. Nothing groundbreaking. But his work sparked the imagination of a young musician named David Porter, who strode into the studio one day and asked if he could lay down some tracks.

Long story short, Porter recruited some other artists who became a band known as Booker T. and the M.G.s – eventually the studio’s de facto house band. Suddenly, the label – named STAX as a combination of Jim and Estelle’s last names – was off to the races.

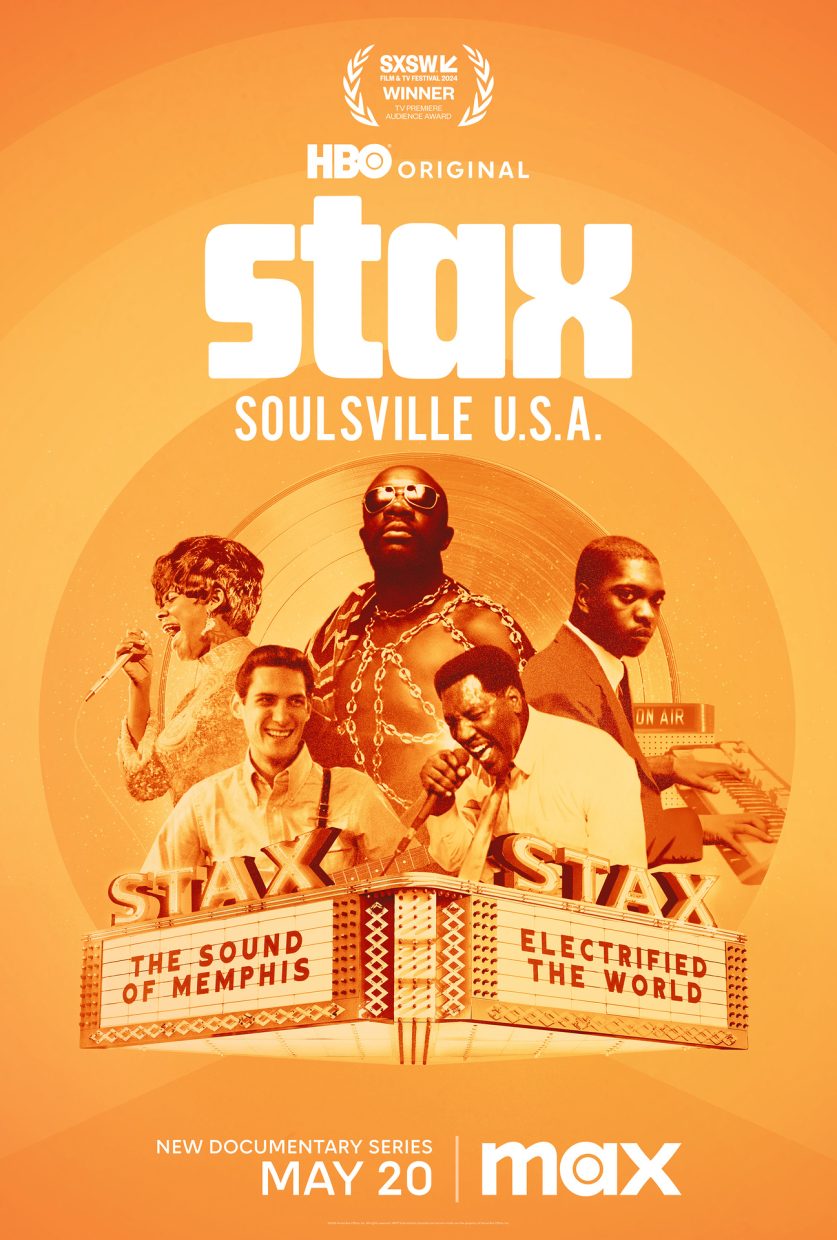

Now, a three-part docuseries from HBO titled STAX: Soulville USA is available for streaming on MAX. The series premiered at South by Southwest earlier this year and earned two Emmy Award nominations (Outstanding Documentary or Nonfiction Series and Outstanding Sound Mixing for a Nonfiction Program). While the series did not prevail in those categories, it is a powerful, thorough, emotional telling of the relationship between music, its makers, and the world in which they live.

The series’ director – Peabody, Emmy, and NAACP award-winner Jamila Wignot – strung together an incredible array of rare and never-before-shared footage of the rise and fall (and rise again) of STAX Records between 1961-1975. But footage isn’t just from inside the studio walls. We see musicians on their first trips to Europe, relaxing in the pool at the Lorraine Hotel – a frequent STAX hangout before it became the scene of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. There is footage from civil rights protests and speeches and moments of great grief and outrage. There are contemporary interviews with the musicians and staff of STAX and Satellite Records, including Axton and Stewart.

And always, at the heart of it all, there’s the music.

In a For Your Consideration panel also available on MAX, Mignot admitted that, when she was approached to direct the series, she was “really just into it for the music.”

“I thought it was going to be this great-big, beautiful music story,” she adds. “As I started to do more research, and particularly looking into the work that [STAX biographer] Rob Bowman had done, I understood that it was a much bigger story that touched on social issues, history, and [it] really was this beautiful story of these folks who were, I think, led by intuition and desire, and weren’t necessarily trying to do more than the things that they loved. But they were very responsive to the world that was around them.”

Of course, outside the walls of STAX studio and Satellite records, Black people were subject to the cultural and legal realities of living in the Jim Crow South.

“[Jim Crow] was too strong a system to tear down,” bandleader Booker T. notes. “In Memphis, you had to keep your mouth shut and hope for the best. Or fight.”

While that was the rule of the road outside, inside STAX studio, Booker T.’s band had two Black members and two white. Together, they developed an approach to Southern soul music that would become one of the most influential sounds of the 20th Century.

Granted, as the civil rights movement went through its various waves in Memphis and beyond, and STAX players marched on picket lines without their white bandmates beside them, this complicated interpersonal relationships in the studio. But the music continued to compel everyone forward. As a result, music fans got to find solace in some of the greatest roots recordings ever made.

The docuseries’ executive producer Michele Smith commented on the artists’ legacies in a recent phone conversation.

“Those artists were just teenagers who had a love for the music,” she says. “[They] just wanted to be heard. What they did not know at that time was they were forging a path to history. They were working, they did know that what they were doing was technically illegal in the Jim Crow South. … They were young people who just wanted to make music. And they did a whole lot more than that. Their music, to this day, will … outlive all of us. It’s globally renowned and it’s some of the best R&B soul music out there, sampled by young people today.”

Being able to watch this music get made is certainly one major draw of the series. Isaac Hayes and the Bar-Kays developing the “Theme from Shaft”; Sam & Dave rolling out “Soul Man” for a live audience the first time; and Otis Redding onstage at the Monterey Pop Festival.

In interview clips, STAX alumni recall how out-of-place Redding and his band were – sober and polished in their well-pressed suits – among the mostly white hippie, dropped-out crowd. Recognizing the one thread that connected him with his seemingly polar-opposite audience, Redding started his set by asking, “This is the love crowd, right? We all love each other, don’t we?” The crowd roared, so he closed his eyes and lit into “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” with a passion and emotional clarity that was absolutely intoxicating.

“Otis Redding hit the stage,” recalled trumpet player Wayne Jackson. “All those hippies got quiet. They ain’t seen anything like us.”

Though that was the truth, it often was in those days of STAX artists making the rounds with their groundbreaking sound. But, certainly, nobody present for any of it – no matter if STAX was on its way up or its way down – would ever forget the way the music turned their soul.

Watch STAX: Soulsville USA via MAX.

Images courtesy of HBO.