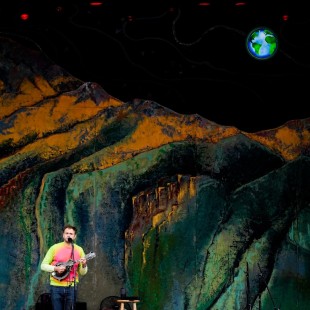

(Editor’s Notes: Headline image of Béla Fleck & the Flecktones. Scroll to see a photo gallery.

To mark Planet Bluegrass’s 50th annual Telluride Bluegrass Festival, we asked author and music journalist David Menconi to reflect on its impact – and the vibrant community that’s grown up around this iconic roots music event.)

The circuit of roots music festivals in America has some similarities to the Professional Golf Association. There’s at least one festival as well as one golf tournament pretty much every week of the spring, summer and fall. But a few stand out as special and even career-making – golf’s four major championships, and the handful of prestigious main-event music festivals. North Carolina’s MerleFest is like The Masters, the early-season springtime kickoff each April, while late-season festivals like San Francisco’s Hardly Strictly Bluegrass line up nicely with the British Open.

But there’s no question which music festival stands as the summit of the circuit, and not just because it’s in the mountains of Colorado. That’s the Telluride Bluegrass Festival, which marked its 50-year anniversary with the 2023 edition last weekend, June 15-18. The fact that Telluride has prospered for half a century makes Telluride something like golf’s U.S. Open championship, the big one that everybody wants to be a part of. Telluride’s status is something that the musicians who play it are well aware of.

“Festivals and musical trends come and go, and acoustic music has been through some serious peaks and valleys the last 50 years,” says Chris “Panda” Pandolfi, banjo player for Telluride regulars The Infamous Stringdusters, who were on this year’s lineup. “The one mainstay throughout has been Telluride Bluegrass Festival. When we started out, Telluride was the place to be and the definitive crossroads we aspired to, and it still is. Lasting 50 years is an amazing testament to its importance. Bluegrass is more popular than ever now, and Telluride is a big part of that.”

There are literally hundreds of music festivals spanning every style imaginable nowadays, including massive annual gatherings like Bonnaroo in Tennessee and Coachella in the California desert. But there were just a small handful of festivals when Telluride Bluegrass Festival started up in 1973 in the scenic Colorado mountain town that bears its name. And even though Telluride’s daily capacity of 10,000 fans is significantly smaller than a lot of the other major festivals on the circuit, it has still maintained its prestige status.

In spite of that smaller size, Telluride does have a few structural advantages that set it apart. One is a picturesque setting of surpassing natural beauty on the western edge of Southwestern Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. For performers as well as attendees, there’s not a better view anywhere than what you see at Telluride.

“The view from the crowd is amazing, but from the stage it’s the most incredible view imaginable as an artist,” says Pandolfi. “It’s this multi-layered inspirational snapshot of some of the best music fans, at the best-run festival, in the most beautiful environment in the world. I think a lot of people have this experience, knowing of Telluride as this iconic festival with an outsized reputation, but it more than lives up to the hype. First time we played there, I remember feeling intimidated because so many heavy-weight players we looked up to were there. But as soon as we got onstage, everything clicked.”

Another major difference between Telluride and its festival peers is scale, and not just in terms of the size of the crowds. Most festivals cram as many performers onto as many stages as possible, all of them running simultaneously, resulting in sensory overload as well as the fear that you’re missing out on something elsewhere. By contrast, Telluride still has just one stage. Every act gets a solo spotlight at Telluride.

“Every year’s festival lineup is an interesting thing,” says Craig Ferguson, who oversees Telluride Bluegrass Festival under the auspices of Planet Bluegrass. “I’ve always said, just watch and it will book itself, and that’s really true. Our process is unique because we have just the one stage and not a bunch of bands, so everybody in the crowd gets to have the same experience. There’s not 18 different stages, so we can create one festivarian experience that everyone shares. We do the booking one act at a time, and we often wind up with interesting combinations.”

Indeed, those interesting combinations can venture well beyond what you see at a typical folk or bluegrass festival. Along with Sam Bush, Emmylou Harris, Peter Rowan, Del McCoury and The Infamous Stringdusters doing a Sunday morning gospel set, this year’s lineup features ringers like the West African ngoni master Bassekou Koyate and the venerable jam band String Cheese Incident. Some of the anomalous acts from previous years include pop-star jazz pianist Norah Jones, the comedic folk duo Tenacious D and even singer/rapper/actress Janelle Monae. Even with the unlikely acts, the Telluride experience sells itself. It doesn’t take much convincing to get any artist to play.

“Janelle Monae was the most interesting person to talk to,” Ferguson says. “I snuck into her RV just as she was sitting down to a meal by herself, and I was able to sit and talk to her for an hour. I think she would’ve signed up to play every year if she could have, she was so enthralled by the fact that there were elk in the park. It was the most wonderful conversation, and she was great. We’re famous for our curveballs and she was the oddest, I’ll give you that.”

Apart from the change-ups, multiple generations of musicians in the world of acoustic music count Telluride among their major artistic, career and personal milestones. One of them is Sarah Jarosz, a four-time Grammy winner who first went to Telluride as a fan at age 14 and played it herself for the first time two years later. Telluride is where Jarosz first connected with idols and future peers like Gillian Welch and Abigail Washburn. It’s also where Gary Paczosa saw Jarosz for the first time at her 2007 Telluride debut. He subsequently signed her to Sugar Hill Records and produced her first four albums.

“It’s the quintessential place to see your heroes, and even get to jam with them,” says Jarosz, who is back on this year’s lineup. “You’ll hear, ‘There’s a jam at this house down the street after the shows.’ So I brought my mandolin and before I knew it, Chris Thile was showing up. Also Jerry Douglas, Tim O’Brien. That was really life-changing, this proximity to heroes that allowed me to become friends with them. And even though Telluride is rooted in bluegrass, they always bring in artists from beyond that world – Janelle Monae, Decemberists, Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. It feels like anything can happen, and the audience that goes is very supportive of that.”

Still, no matter how far afield the lineup wanders, Telluride is ultimately rooted in bluegrass.

“Bluegrass is a fable, and a team sport,” says Ferguson. “That informs how we create the lineup. Looking to the future, socially as well as musically, we think of bluegrass as an allegory. It’s a context that is invitational to all these other styles, country or jazz or classical, and it complements all of them. That remains the heart and soul of this festival, surrounding bluegrass with these other complimentary musics. We are fortunate to be of service to the festivarian community. It’s an annual privilege to see how much it brings to people’s lives, the connection to community.”

All photos by Maya Benko, courtesy of IVPR