Dale Ann Bradley has made a lasting impression with bluegrass listeners as a solo artist, as well as a member of the all-female band Sister Sadie. And before that, she recorded and performed with the New Coon Creek Girls in Renfro Valley, Kentucky, where she established a foundation that would carry to her multiple performances on the Grand Ole Opry and five IBMA awards in the female vocalist category.

An approachable artist who describes her audiences as “my people,” Bradley is quick to admit that her musical path hasn’t always been easy – in fact, her new album is named The Hard Way, a nod to the Jim Croce song she covers, “The Hard Way Every Time.” But in spite of that title, it’s a beautifully subdued project that stands among the most satisfying of the Kentucky native’s long career. That’s as much due to her gentle singing as her gift for finding songs that suit her.

Bradley invited the Bluegrass Situation to chat prior to a Nashville show earlier this month at the Station Inn.

BGS: I wanted to start by asking about the production on this record, because to me it sounds very crisp. It seems like there’s a “less is more” approach.

Bradley: It is. I have learned, on some things, that’s the correct approach. This one’s more guitar-oriented than a lot of them I’ve done – since [1997’s] East Kentucky Morning. Because I had such good guitarists play, it really didn’t need to be souped up. And the lyrics are so story-telling that the song, and the great musicians that I had, found their own way and their own place to be. … This is the third one I’ve produced and I’m always scared to death! I never take that for granted because it’s just like painting a picture or having a young’un! [Laughs] You don’t know what’s going to happen.

What is it about production that makes you want to keep coming back into that role?

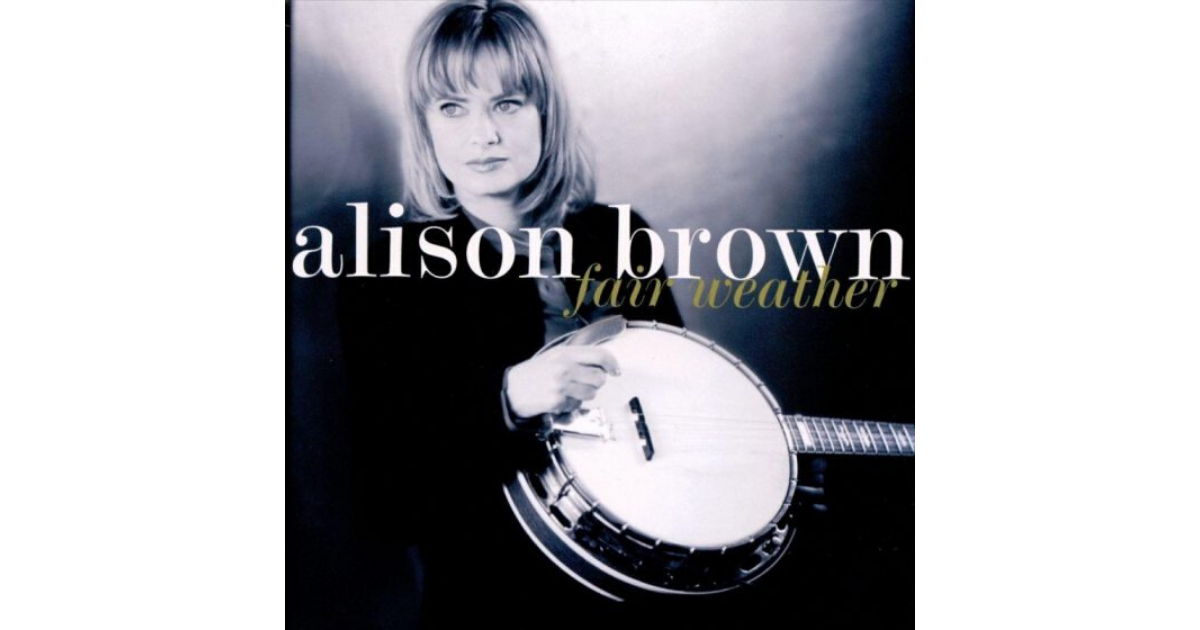

If I want to try something, to able to do it. Even though I know that sometimes it works and sometimes it don’t. I have the utmost respect for any producer that I’ve had because I’ve had the best there is. … From Sonny Osborne, I learned that a good performance is a lot better than everything being technically perfect. He drilled that into my head – it’s all about emotion. With Tim Austin, I learned drive and punch with the guitar, and he helped me a lot with my guitar playing. And with Alison Brown, I learned not to be afraid of creativity. Put it down, and if it works, it works. And if it don’t, then you’ll know not to do it the next time. She’s so creative. I’ve worked with three different producers with three different outlooks, and learned from all of them.

“The Hard Way Every Time” is a beautiful song, with a lot of truth in there.

It is for me. The generation that I come from, we’re all at that point where we’re looking back, and we think, “Well, I sure did that the hard way.” Kept doing it and kept doing it. I hope it reaches a young generation. It seems to be, but I think there’s something in there hopefully for everybody.

How do you find the songs you want to record?

All the memories… I may not be able to recall what I had for lunch or breakfast, but a song will stay with me. Songs that have been poignant in my life have been so much so that I’m never going to forget them. I don’t cut cover tunes just to be different. I do it because it shows how talented these musicians are. … And I want to show that in music it doesn’t really matter what genre it is. If it really breaks your heart or makes you happy, it’s all good. Then there are songs that I want to do in the bluegrass style because I didn’t want to do them in the other style.

I’ve often thought that there might not be any song that’s off limits for you. Is that true?

Well, it was close this time. I’ve never been as scared as I was with “Wheel in the Sky.” I really belabored it. Everybody was saying, “Let’s cut it,” but what do you do after Steve Perry’s cut something? Or Journey’s played it, you know? Then I got to looking at it some more. That was probably the last song that I picked. And I got to listening to those lyrics, and I thought, Bill Monroe would have wrote that: “Winter’s here again, O Lord…”

And I’ve done that with other songs, like “Summer Breeze.” The lyrics are just about life and emotions, and it’s important to me. I love novelty, funny little songs but I just really like the ones that have a message, or maybe leave one.

How did the guitar come to be your instrument?

It was probably going to be the only one that I had any possibility of getting. I would have loved to have had a banjo and mandolin, but I finally got a little ol’ cardboard, classical-style guitar that somebody ordered from a catalog. I knew I might get that one if I pressed enough. If I pressed too hard, I wasn’t going to get nothing! But I had a love for it. And still do.

I never was around anybody that played, is the thing. I had a friend who was my age, and we wrote songs together. He was very talented and he didn’t play bluegrass-style. He was a Jim Croce fan, so he would play that and I was so mesmerized, but that was the only guitar influence I had until I came to Renfro Valley. They were all seasoned Central Kentucky musicians and I learned so much from them.

You were at Renfro Valley for years, and then you became a bandleader. What do you remember most about that time? What was that transition like for you?

It was a transition that had to take place, before I would have ever gotten out of the community I was from. I learned a lot about the history. I learned Bradley Kincaid songs and who Bradley Kincaid was, and how Renfro Valley is such a treasure. I loved it and I got to perform country and gospel. I started singing traditional country there, and then the entertainment director would let me do traditional bluegrass songs with the country band. And that worked out good.

When that position with the Coon Creek Girls came open, I was tickled to death to get that. … Renfro Valley is in “The Hard Way Every Time.” Major, maybe over 50 percent! [Laughs] But I learned, and I’m thankful now that I learned those hard life lessons with good people that had hearts. I was thrilled to work there. The talent there in the late ‘80s and ‘90s – I’m telling you, it was as good as you’d hear anywhere.

And then you decided you wanted to be in front, and go on tour?

Well, what happened was, the Coon Creek Girls had been together for years and everybody got married and had babies. I still didn’t want to step completely out, so we called it Dale Ann Bradley and Coon Creek. And then things changed from there, and I signed with Compass, and then it grew its way into me totally being responsible. [Laughs] Good, bad, and indifferent!

What is some of the best business advice you’ve ever gotten.

[Laughs] Don’t spend your money! Cut corners, but not so much where you make somebody uncomfortable. But when you can, cut corners. Don’t buy what you can’t pay for. And work hard. Respect your money. I had to learn that the hard way, too — that’s the other 50 percent of The Hard Way!

Who would you say are some of your heroes?

Oh, Dolly Parton of course. I loved John Duffey and John Starling. What got me really hooked on bluegrass was that I’d hear Ralph Stanley and Bill Monroe on the radio — and Lester and Earl on The Beverly Hillbillies when I got to see that. Dolly was a hero, and the Seldom Scene, The Country Gentlemen, Charlie Waller, so many in the country field, too. Dolly could do anything. Bluegrass was naturally there, with her being 80 miles across the mountain from where I was from. And I loved Glen Campbell – he was another one that could do everything. So many that you can’t name.

So many of those artists you named have an incredible ear for a song.

They do, and it’s a gift that they can sing anything. And I adore Aretha Franklin, Stevie Wonder, and Ray Charles. You can’t stay on this earth and get any better than that.

You’ve won some IBMA Awards, and Sister Sadie earned a Grammy nomination this year. I would imagine that aspiring musicians may look to you as a role model. Do you see yourself that way?

Well, I don’t feel that I’m even worthy enough to put myself up as a role model. But if they like this style of music, I want to be somebody that makes them unafraid to express themselves. And I’ve always tried to treat people as good as I can. In those two ways, I hope that I am. In other ways, everyone’s got to walk their own journey, you know?

The IBMA Awards now have women winning the instrumental categories. As a woman in bluegrass yourself, what does an accomplishment like that mean to you?

Well, obviously it’s good that the mindset has changed, in order to really study the female musicians because some of them are quite great. The thing that worries me a little bit is that I don’t want it to matter if it’s male or female, if you’re a good player. I know so many females who are wonderful players and I don’t think we should get it just because we’re women. Let’s get it on our playing and our accomplishments. I don’t get into that (mentality of) “you’ve got to let me play because I’m a girl!” [Laughs] I’ve never been thrown out of a jam session, but I ain’t been in too many either.

Do you see a difference from when you started until now?

Definitely. I see girls cutting their gig, is what I see. Learning. And playing and singing and writing. I do see a female presence strongly coming in there. There was a time of course, I know not so very long ago: “Well… girls can’t sing bluegrass.” Now that needed to go!

I’d like to see the festival scene open those doors more.

Yeah, they’ve moved up to about two girl acts. And I didn’t really realize that was the case, because in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the Coon Creek Girls were the girl act. [Laughs] And I thought, “We’re getting hired, what’s the problem?” “Well, you’re the only girls!” [Laughs]

Going back to the title of this record for a second, I know there’s a lot of hard work that goes into a career like yours. But what would you say is the reward in that?

Oh gosh. There’s been so many. The reward was that I was able to do it. I was able to sing from the very first venue until now. I got the opportunity to sing and to write and to express myself in a musical way. I’ve met the most precious angels — and a lot of musicians have. They’re angels themselves. So many good friends that have been so good and gracious and merciful to me. And along with that, it provided a way for me to support myself and my son. That’s the reward. That right there is everything.

Photo credit: Pinecastle Records