Saxophone, mountain dulcimer, mandolins, banjos – what else could you need? Our weekly new music round-up is here!

Today, we complete our mini-series with saxophonist Eddie Barbash with a video for “Fort Smith Breakdown,” an old-time fiddle tune performed exquisitely by Barbash on sax in a lovely, natural setting. You can find links to watch all four of Barbash’s live performance videos from his upcoming project Larkspur, below. On the other end of the roots instrument continuum, perhaps the South’s most accomplished and technical mountain dulcimer player Sarah Kate Morgan teams up with fiddler Leo Shannon on a new album, Featherbed, out today. To celebrate, we’re sharing their track “Belle of Lexington,” which they first sourced from a Library of Congress recording made in 1941 before crafting their own arrangement.

Bluegrass stalwarts Chris Jones & the Night Drivers offer a delightful play on words with “Under Over,” a song Jones wrote with broadcaster-songwriter Terry Herd. The uptempo, straight ahead bluegrass single is available today wherever you stream music. Jones’ labelmate, mandolinist and singer-songwriter Ashby Frank, also launches a new single today, too. “Mr. Engineer” is a Jimmy Martin and Paul Williams classic that Frank has performed for years, but only just recorded for the first time.

Alt-Americana rockers Keyland release their new EP today, so don’t miss the title track to Stand Up To You below. As you’ll hear, this soulful Oklahoman outfit blend so many roots genres together into a melting pot style all their own. Singer-songwriter Jon Danforth then takes us just across the state line to Arkansas with his new single, “Arkansas Sunrise,” which will be included on his upcoming 2026 album, Natural State. Dripping with childhood memories and nostalgia, it’s an homage to his home state and its moniker, from which he pulled the title of the new LP.

Plus, don’t miss the new music video for a just-released single from singer-songwriter Abby Hamilton, too. “Fried Green Tomatoes” was inspired by a line uttered by Idgie Threadgoode of the novel (and film) Fried Green Tomatoes. The vibey country-folk track explores relationships and friendships – and the parts of ourselves we display or keep hidden away.

There’s plenty to explore and enjoy from all corners of the roots music landscape! You Gotta Hear This…

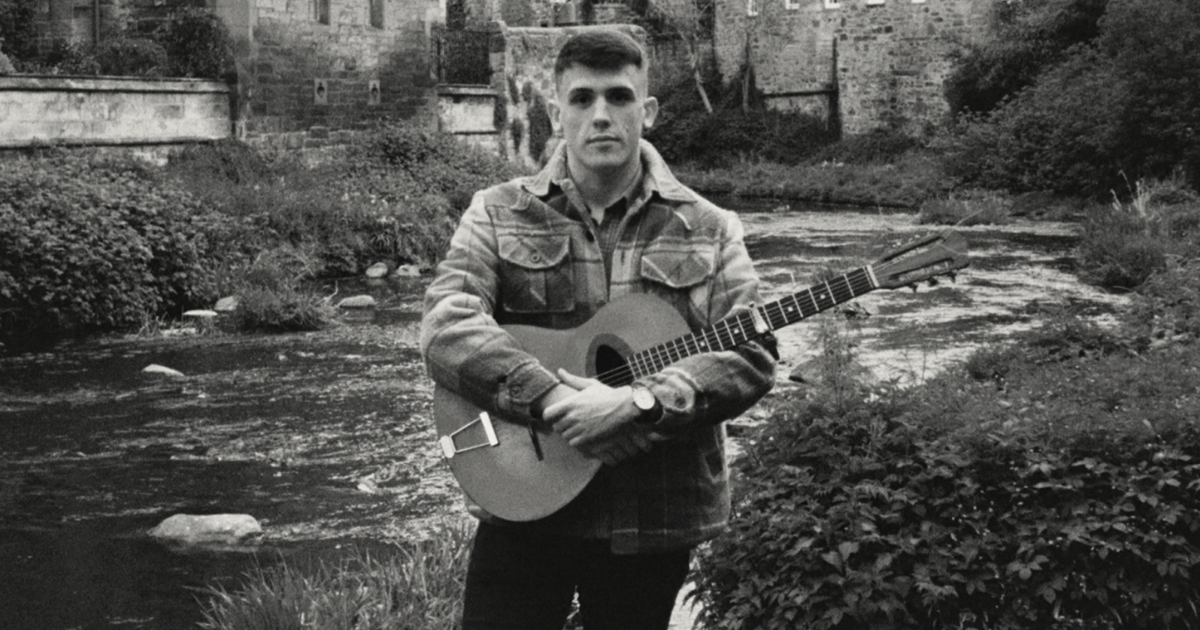

Eddie Barbash, “Fort Smith Breakdown”

Artist: Eddie Barbash

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Fort Smith Breakdown”

Album: Larkspur

Release Date: November 28, 2025 (The album will be released one song at a time with the last track coming out Nov. 28).

In Their Words: “I learned ‘Fort Smith Breakdown’ from a great Floyd, Virginia old-time fiddler named Earl White. My favorite old-time guitarist Danny Knicely was playing with him at the time and called it ‘that tune that goes to the 4 all of a sudden.’ This practice of adding or dropping beats in unexpected places is one of my favorite things about the old-time tradition. Four of the nine tunes that I chose for Larkspur are ‘crooked’ like this. We made this recording on a trail through the Larkspur Conservation area’s natural burial ground. After two days on the grounds, I’m completely sold on natural burial. I’d much rather feed the forest and donate my body to the preservation of wild land than to rot alone in a concrete box under a lifeless lawn.” – Eddie Barbash

(Editor’s Note: Watch all the videos in our mini-series with Eddie Barbash here, here, and here.)

Jon Danforth, “Arkansas Sunrise”

Artist: Jon Danforth

Hometown: Dallas, Texas

Song: “Arkansas Sunrise”

Album: Natural State

Release Date: October 24, 2025 (single); January 23, 2026 (album)

In Their Words: “‘Arkansas Sunrise’ is about the countless, lazy Saturday mornings I’ve spent in my home state with family and friends. Arkansas is a beautiful state and a wonderful place to be, especially in the fall when the hot temperatures finally drop. There is nothing better than waking up to cool weather, leaves changing, and bacon crackling alongside the people you love. My goal was to capture that warmth and nostalgia in a song that hopefully honors my home state.” – Jon Danforth

Track Credits:

Jon Danforth – Vocals, acoustic guitar, songwriter

Will Carmack – Bass

Aaron Carpenter – Drums, percussion

Bobby Orozco – Piano

Melissa Cox – Fiddle

Hannah Brooks – Background vocals

Ashby Frank, “Mr. Engineer”

Artist: Ashby Frank

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Mr. Engineer”

Release Date: October 24, 2025

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “I started performing this Jimmy Martin and Paul Williams classic on stage with Mashville Brigade years ago and recently started adding it to the set list of my Yachtgrass band’s shows. I have wanted to record it since I started singing it live and I am so proud of the finished product. I just love the old school vibe and super lonesome content of the lyrics and melody, and of course Matt Menefee (banjo) and Jim VanCleve (fiddle) added some wicked and bluesy solos that made the whole track gel. I can’t wait for everyone to hear it!” – Ashby Frank

Track Credits:

Ashby Frank – Mandolin, lead vocal, harmony vocal

Seth Taylor – Acoustic guitar

Travis Anderson – Upright bass

Matt Menefee – Banjo

Jim VanCleve – Fiddle

Jaelee Roberts – Harmony vocal

Abby Hamilton, “Fried Green Tomatoes”

Artist: Abby Hamilton

Hometown: Nicholasville, Kentucky

Song: “Fried Green Tomatoes”

Release Date: October 24, 2025

In Their Words: “‘I’m as settled as I’ll ever be,’ is the line from Idgie Threadgoode in Fried Green Tomatoes that inspired this song. It’s about the inner dialogue in relationships and friendships as you never show the world what you question from within. The world sees you as secure and confident, which you very well may be in some ways, but inside you feel a sense of doubt that no one else knows. Maybe just the most intimate of friendships or relationships get questioned. That in whatever you’re carrying on about inside or out, it’s still ‘look at those fried green tomatoes’ in the middle of ‘she’s trying to teach me how to cook.’ Chaos and joy and confusion. You can be all out of sorts about whatever’s in your brain and it’s still just ‘fried green tomatoes.’ The right person will make you laugh and ground you, remind you that you’re not so alone.” – Abby Hamilton

Chris Jones & the Night Drivers, “Under Over”

Artist: Chris Jones & The Night Drivers

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Under Over”

Release Date: October 24, 2025

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “I have no idea where the phrase ‘file it under over’ came from; it was just one of those things that popped into my head one day. Aside from the play on words, I just got to thinking about the idea of filing something away for good, whether it be a bad relationship or an addiction of some kind, and I pictured a file with ‘over’ on the tab. I’ve been friends with songwriter and bluegrass broadcaster Terry Herd for many years and he’s written all sorts of award-winning and hit bluegrass songs with a range of writers. But we had never written one together and it’s been something I’ve wanted to do for a long time. We discussed the song concept together when I was at his house in Nashville and we got right to work on it. He was the one who came up with the phrase ‘in a little box of pain,’ which I think is my favorite part of the song. The uptempo, straight ahead bluegrass feel really fit with the uplifting feeling of filing something negative away and moving on.” – Chris Jones

Track Credits:

Chris Jones – Acoustic guitar, lead vocal

Jon Weisberger – Bass

Mark Stoffel – Mandolin, harmony vocal

Grace van’t Hof – Banjo, harmony vocal

Tony Creasman – Drums

Carley Arrowood – Fiddle

Keyland, “Stand Up To You”

Artist: Keyland

Hometown: Tulsa, Oklahoma

Song: “Stand Up To You”

Album: Stand Up To You (EP)

Release Date: October 24, 2025

Label: One Riot

In Their Words: “I’m hoping this song feels like you’ve heard it before and you can’t remember where or from whom. I think most of my favorite music has this effect on me – whether it’s from 1965 or 2025. When I listen to music like this, I feel like I’ve known it forever. And not in a redundant, boring sense, but in a way that feels as though that particular song has just always existed in some deeper, elusive but still tangible reality. Like you’ve always known it, but you can’t exactly remember how.

“I’m unsure if we’ve actually accomplished that, but hopefully it is somewhat close. I also love music that makes you feel like you are in the same room as the artist. I think live-tracked recordings have a lot to do with this particular effect, so we leaned into that with this song – as well as a few others on this EP. I was listening to a lot of Ray Charles, Stones, and Faces (and will always be) when I wrote this one, so I’d guess that will come through as well. In the words of Taylor Goldsmith, ‘Anyone that’s making anything new only breaks something else…'” – Kyle Ross

Sarah Kate Morgan & Leo Shannon, “Belle of Lexington”

Artist: Sarah Kate Morgan & Leo Shannon

Hometown: Hindman, Kentucky (Sarah Kate); Whitesburg, Kentucky (Leo)

Song: “Belle Of Lexington”

Album: Featherbed

Release Date: October 24, 2025

Label: June Appal Recordings

In Their Words: “This is a very old fiddle tune which I learned as a teenager in my mom’s living room in Seattle, Washington. The source is a recording of fiddler Emmet Lundy made by the Library of Congress in Galax, Virginia in 1941. (Many thanks to the Slippery Hill archive for facilitating this transmission.) Eighty-four years later, our performance of the tune was recorded live at The Burl in Lexington, Kentucky by the intrepid Nick Petersen. We dedicate this track to all the beautiful people in all the Lexingtons around the world.” – Leo Shannon

Photo Credit: Eddie Barbash by Jeremy Stanley; Chris Jones & the Night Drivers by Brooke Stevens.