Because they have developed a fan base that stretches across genres and generations, it isn’t so easy to, ahem, segment Mandolin Orange into one specific category. But throughout a decade of performing together, bluegrass has been a major part of the music created by the duo’s Andrew Marlin and Emily Frantz. In the second part of our BGS cover story, they discuss their biggest bluegrass influences.

Editor’s Note: Read Part One of the BGS Cover Story with Mandolin Orange.

BGS: There’s a real country feel on “Lonely All the Time.” Are you classic country fans?

Andrew: Yeah. It’s not something I dig into, and really break apart, like I do with old-time and bluegrass music, but I think Emily and I both grew up listening to classic country. My dad is a country music fan, and that was a song that inadvertently got written from his perspective, living alone these days. I wanted to do a classic country duet sound for that, and Emily had the idea to do harmony all the way through it, like a George Jones and Melba Montgomery tune.

Emily: I think our road to classic country has been more roundabout. We listen to a lot of bluegrass, and when you listen to a lot of the older country, it’s a lot more acoustic and smaller-sounding, sonically. A lot of it is not very different than standard bluegrass tunes. It feels like that’s a natural path for us to go down with this band.

Andrew: Yeah. I like Hank Williams and early Johnny Cash, where it’s just a small ensemble playing the music.

Who are some of the bluegrass musicians you return to, just for enjoyment?

Emily: Andrew spends a ton of time listening to Bill Monroe, from a place of really digging into mandolin, and I guess for enjoyment too. But for listening pleasure, I would say a lot of the brother duets – the Stanley Brothers, the Louvin Brothers…

Andrew: Yeah, the Stanley Brothers for the songs, too. They were lonely, man. They were lonely dudes! I think the Stanley Brothers had a natural, bluesy feel, and their songs were so heavy and beautiful. Definitely, for songwriting, the Stanley Brothers would be a big influences, especially on our tune, “Suspended in Heaven,” on the new record. But also the Sam Bush and Tony Rice era. I listen to a lot of Sam Bush and Tony Rice, and just keep getting farther and farther into the Sam Bush catalog. I love his energy and what he brings to whatever ensemble he’s playing. It’s cool that he has a documentary out about him now. He’s getting the respect that he is due.

You may never emerge if you dive too deeply in Sam’s catalog. That stuff is so great, and sounds so good at festivals. He’s like the king of festivals.

Yeah, I think that’s because he’s able to maintain what he wants to do musically, but he’s still energetically appealing to mass audiences. That’s a hard to thing to do at a festival and I feel like he does it well.

That festival crowd can be tough. How many festivals have you all played over the last 10 years?

Andrew: We’ve played a bunch of ‘em. And playing quiet music. That can be an intimidating thing sometimes.

How did you overcome that?

Andrew: We shut our eyes and just hope they don’t mind hearing some quiet music. (laughs)

Emily: I think it was actually realizing that there is a place for that at festivals, even though it doesn’t seem like it. We’d get on stage and feel outgunned at the outset, but the more that we talked to people and realized that they appreciated having that in their festival experience, to offset all the crazy jamming going on. Everybody needs to balance out a bit. Once we realized that, we were able to own it a little more and recognize that that could be our role.

Andrew: It’s more like the hangover weed crowd than the late night drunk crowd, I would say.

I want to go back to “Suspended in Heaven.” It does have that Stanley Brothers sound, but it also has that church music sound, in a way. Are you influenced by music of the church?

Emily: Probably more in that we listen to and enjoy the old gospel tunes that are part of the bluegrass repertoire. We both grew up with church music but it wasn’t necessarily this kind of church music.

Andrew: My mom’s mom was the piano player for the church I went to, growing up, and then my mom took over her responsibilities, then my sister took over for a little while. So it’s like three generations of piano players at this church in Afton (North Carolina) that we went to, growing up. I was around a lot of old hymns and old gospel music, and you can’t really separate my mom from gospel music. I think in wanting to pay homage to her, and to her life, it made sense to write a standard old gospel tune. I guess the lyrics are not traditionally leaning but the sound definitely is.

Tell me how you became interested in bluegrass music.

Emily: For me, it was in the very beginning when I was taking Suzuki violin lessons as a kid. Our teachers didn’t give lessons in the summer but they did fiddle camps. I always played by ear but that was my first experience of being encouraged to learn to play by ear and not being forced to read sheet music. So I learned “Old Joe Clark” and “Bile ‘Em Cabbages Down” – all the first fiddle tunes you learn. And gradually I phased completely out of doing anything classical.

I was able to take more fiddle lessons and play in a local bluegrass band around the time I started high school. And learned a ton from the guys I was playing with, about how to sing tenor and what role the fiddle is supposed to play. It’s cool that traditional bluegrass has pretty hard-and-fast rules about what the given instruments are supposed to do, and I’m really glad that I learned that. We don’t play that way ourselves, on our own tunes necessarily, but it’s really fun to jump in and make a bluegrass song sound just like bluegrass-–if you know the rules.

Andrew, how about you?

Andrew: I’d only just started getting into bluegrass when Emily and I met each other, actually. I grew up with country and switched to rock ‘n’ roll, and then from there I fell into a metal zone. I was in a metal duo, actually, before I moved to Chapel Hill. I don’t think there are any recordings of that out there – hopefully not. I credit the Skaggs & Rice record a lot as being that switch for me that flipped me to bluegrass. When I heard that, I was like, ‘Who is this guitar player?” And the way they are singing together, it’s really quality. Especially Ricky Skaggs’ mandolin playing on that record.

So from there, I found out about Norman Blake and David Grisman and John Hartford and of course Sam Bush. I just fell in love with it, and especially the mandolin. So I think when Emily and I first met, I’d only been playing the mandolin for a year or so.

Emily: Andrew didn’t know very many bluegrass tunes. I was more of the source, at that point.

Andrew: She was showing me a bunch of fiddle tunes to learn on the mandolin, which really helped me figure the instrument out. I’m still figuring it out. So I’d say meeting Emily was a big part of my schooling in bluegrass, in a lot of ways.

After ten years of knowing each other, do you have a good intuition about what the other person is thinking?

Emily: I would say yeah, especially musically. I think all those years, too, of playing just the two of us, it becomes like a second language, and you don’t even necessarily realize it’s happening.

Was there a time when you did realize it was happening? Where you thought, “Wow, this is actually pretty good.”

Andrew: It depends on what we thought the other one was saying. (both laugh)

Emily: I remember reading an interview with Gillian Welch a long time ago, when she was talking about playing with a duo, about how it’s so much harder than playing with a full band, but also how it’s so much easier. And a lot of the things that she said about it made me realize how we were communicating, in a way that I didn’t necessarily realize before.

Andrew: I definitely love the spontaneity of playing in a duo, playing with just one other person. It’s really hard to make that split-second decision to vamp on a chord if you forget a lyric, or to extend a solo section, when there are four other people on stage with you. But when it’s just the two of us, we can kind of look at each other and give an eyebrow raise, and it’s like, “Oh yeah, I forgot the lyrics, so….”

Emily: It’s not even visual sometimes, but if somebody misses something, you automatically compensate for it in some way, and it’s not even conscious. I guess that’s probably possible in larger ensembles but it probably takes ten times as long to get there.

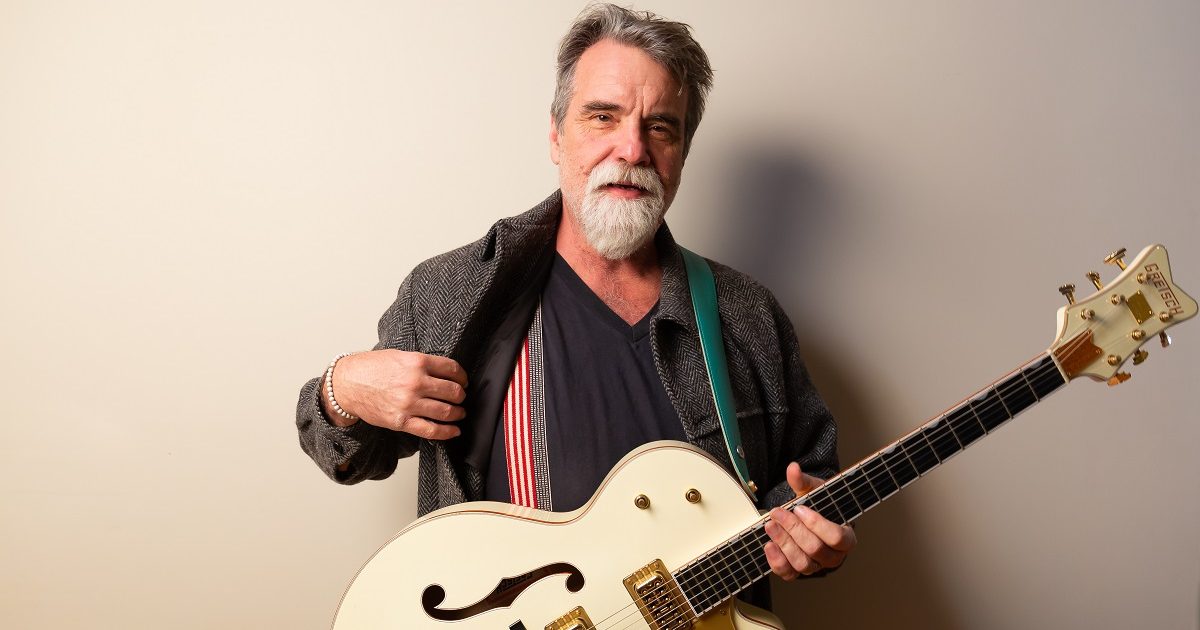

Photo credit: Kendall Bailey