Oftentimes keeping things simple yields the most profound results. Such is the case for accomplished fiddler Tammy Rogers of The SteelDrivers and well-traveled guitarist Thomm Jutz, the reigning IBMA Songwriter of the Year. Surely Will Be Singing, a new compilation of their co-writes, marks their first album together.

Having known of each other through bluegrass and roots music circles for years, the two finally met at a SESAC music industry dinner and awards show in 2016. Although neither won any awards that night, Rogers and Jutz were seated together, leading to the beginning of a long and fruitful friendship. After exchanging phone numbers on their way out of the gala while waiting in the valet line, the two met up at Rogers’ home the following week for their first songwriting session. Coming from that meet-up was “Old Railroads,” a song Jutz recorded for his 2017 album Crazy If You Let It as well as Eric Brace & Last Train Home’s Daytime Highs & Overnight Lows. Since then, Rogers and Jutz haven’t slowed down, writing on average one song per week for an cumulative total of over 140 songs and counting.

BGS: Considering you’ve written over 140 songs together, how’d you go about dwindling those down to the 12 that made it on the album?

Tammy Rogers: It’s a really hard process because we write so much together and love all the songs. They’re all like children to us. That being said, we don’t usually set out with the mindset of writing for Del McCoury or Tim McGraw. We just sit down and write whatever we’re feeling that day. Oftentimes a book, show, current events or just a random conversation will spark an idea. When we started talking about doing this record, the idea of keeping it simple kept coming up. Part of that was because when we began recording, we were still in serious lockdown mode. We knew we wouldn’t be able to get together in a big studio with our friends to record something really grand, so the simplicity was born out of necessity. The songs we chose lend themselves well to simple production.

Thomm Jutz: We also searched our catalogs for songs that would work well as duets. We’re also both big fans of the Carter Family, the Monroe Brothers, the Blue Sky Boys and other early country music. We didn’t necessarily want to make a full-band record. We wanted to have some bands on it, but at this point in my life with my own work I’m really intrigued by just whittling it down to duo and trio stuff with as much simplicity as possible.

Earlier y’all mentioned getting song inspiration from everything from current events to books and even television. Do you try to tie a lot of those themes back into your own lives with your songwriting or do you prefer going the fictional route? Or is it a bit of both?

Rogers: I don’t even know that I could even quantify how that would split because Thomm is the kind of writer who always has his antennas up. Whether he’s reading a book, watching a documentary or just letting his mind wander in conversation, I think he’s always listening for a phrase or thought that could turn into a song. I’m the same way. Just the other day I said something to a friend and immediately thought, “Hey, that’s a song!” I texted it to Thomm and he was on board. It’ll probably be the next song we work on. When you’re a writer and you’re really in the flow of it, anything can inspire. And if something catches your ear, whether it’s a fleshed-out story or a phrase that could be a title, you run with it. I do that all the time without thinking of a backstory. A phrase will pop into my head or I’ll say something and someone will follow up with something else and an idea snowballs from there.

Jutz: It’s important to pay attention. I think that’s the whole job description of a songwriter, or at least 90 percent of it. It’s also important to take good notes, whether it be a verse, one line, a title or just a general idea. I write all that stuff down, but like Tammy, I don’t try to overthink things. It’s important to keep an open mind because if you bring that into a co-writing session someone may interpret something completely different than you. But Tammy and I mostly write off of titles or general ideas. One of the nice things with bluegrass is that there’s a sort of vocabulary that goes with it. There are rules of what you say and how you say things that help us to focus on that structure when we’re writing. It’s like figure skating. You have to do certain poses or jumps to express yourself within the given parameters. That’s something I’ve always been intrigued about with bluegrass and American roots music. There’s a sense of structure already there and you have to try to do right by that.

Tammy, a moment ago you mentioned Thomm always having his antennas up. Going off that, what is it you each appreciate most about one another as songwriters and artists?

Tammy: One of the things I love most about writing with Thomm is that I’m from the Appalachian Mountains of East Tennessee and even though he’s from Germany, he’s studied my part of the world and is familiar with the culture. If I tell him we should try coming at something with a Carter Family approach or the Monroe and Stanley Brothers he knows exactly what I mean. That makes the process so fun and easy. I don’t think we’ve ever argued about a song and the direction it should go. It really allows us to get inside of a song and go to that place.

Jutz: I think what we both appreciate about each other is that we both take the work very seriously without taking ourselves too seriously. That’s not something that either of us came up with, but rather something that William Faulkner said when asked about writing for movies out in California. I think that mindset is a good recipe for a successful collaboration. In regards to Tammy, she’s just so musical. Not to say that other songwriters aren’t, but Tammy and I approach songwriting as instrumentalists. With that comes a different skill set that allows us to communicate differently than with people who work primarily as songwriters only. It’s very different writing with someone who’s a good instrumentalist, which Tammy obviously is.

That’s the second thing I find unique about our writing relationship, it just comes easy. We get along well and we’re close to the same age but have completely different life experiences. Tammy has children and I don’t, for example. Our lives are very similar and very different at the same time, which makes for a great exchange of ideas.

Speaking of the songwriting process, I love the song “Speakeasy Blues” and the Prohibition Era vibes it radiates. Can you tell me about the song’s story and how you pieced it together for the album?

Jutz: It doesn’t really tell the story of a book, but Tammy and I both had just read a book by North Carolina author Terry Roberts called The Holy Ghost Speakeasy and Revival. It’s a really cool story about the prohibition era and a preacher who had his own train and would recruit misfits to join his crew, preaching to them and selling them liquor. It’s a wild story. One day we were talking about it and I remember Tammy saying that “Speakeasy Blues” sounded like a good song idea, and we ran with it.

Rogers: That song is a great example of how Thomm and I write. We share a lot of books and always share stories we enjoy with one another. It’s fun making music with literary sources because not everyone who hears the song has read the book, which leaves some nuances of the song up to interpretation. On that song in particular, after framing it into the Prohibition Era, we sought to make sure it had a fast tempo and driving beat similar to a train because in the book that’s how they traveled. There’s stuff like that that’s almost subliminal that you may not catch as a listener but that we were aware of when constructing it. Those little easter eggs are fun.

Jutz: Another interesting side to that song is that the book’s author, Terry Roberts, wrote the liner notes for our record. After sending it over and asking him to write for us he said he first listened to it while in London and upon hearing the first line of “Speakeasy Blues” said, “That’s Jedediah. That’s the preacher from my book!”

Rogers: I just started reading another book of his called A Short Time to Stay Here. I really like the title, so maybe one day it’ll become a song, too.

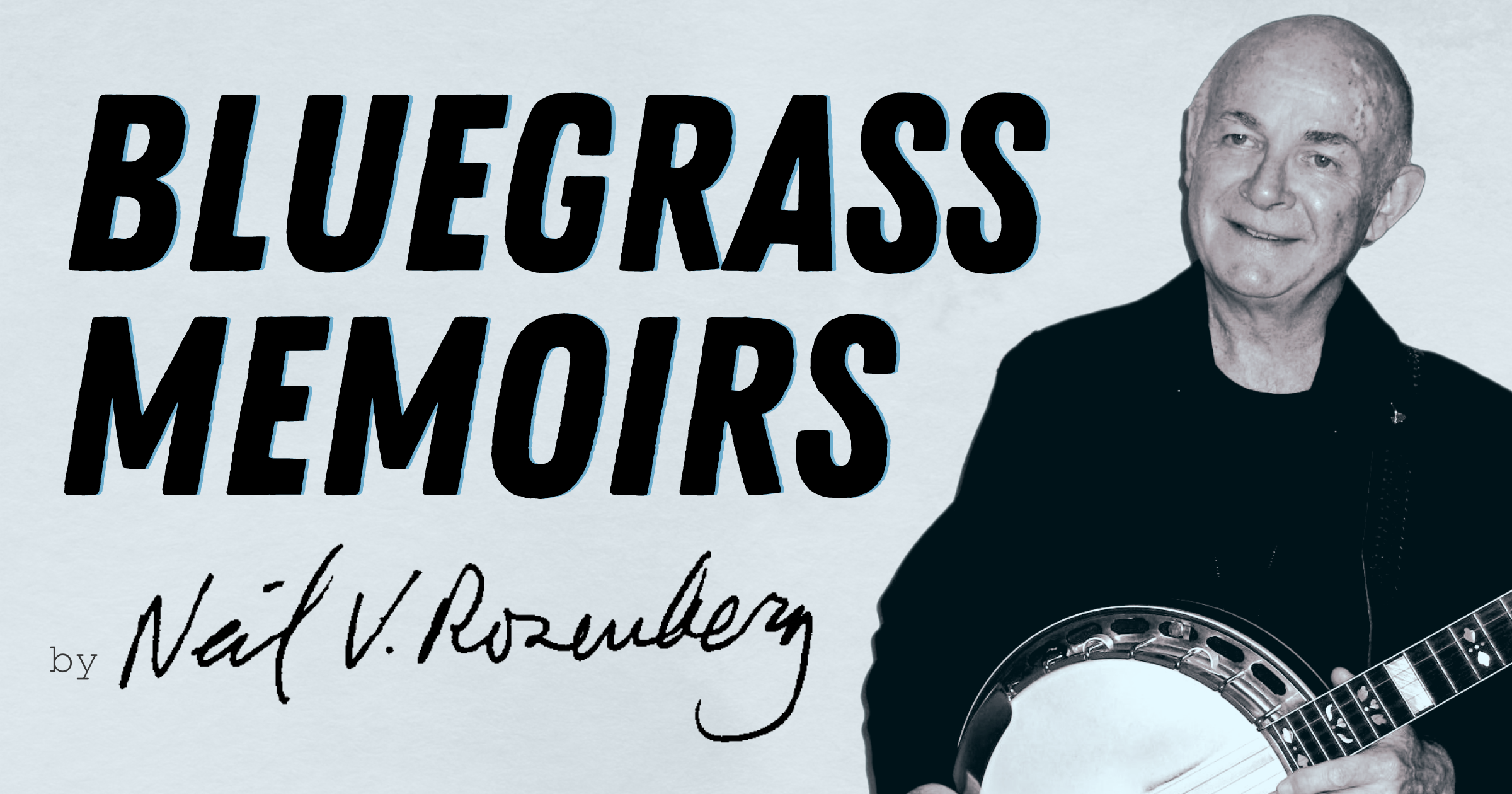

Photo Credit: Anthony Scarlati