Ani DiFranco has long been a voice for social change, using her platform as a widely acclaimed songwriter, activist and record label owner — among the many other hats she wears — to bring attention to societal ills. Her incisive, insightful songwriting has made her into something of a progressive icon, as well as an artist mentioned in the same breath as fellow legends like Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie.

It’s a gift, then, that DiFranco would release a new album — the excellent Revolutionary Love — at a time marked by political unrest, protests for racial equity, and nearly a year into the global COVID-19 pandemic. DiFranco wrote Revolutionary Love before the coronavirus was a household term, but one can easily connect the troubles of our current moment to many of the album’s thoughtful, prescient tracks.

While the COVID-19 pandemic halted DiFranco’s touring, it did open up space for her to spend time with her family and to work on new ideas, like writing a children’s book, starting a free radio station and writing a musical about restorative justice. BGS caught up with DiFranco on the morning of Revolutionary Love‘s release to talk about these recent projects and beyond.

BGS: The album is out today. How are you feeling?

DiFranco: I’ve heard from a few friends. I actually woke up this morning not realizing it’s release day. I’m just trying to function as a human and a mom in a pandemic, and a person without a job, and this and that. Then my phone started dinging at me and it was just near and dear saying, ‘Yay! Woohoo!’ So, I’m all of a sudden feeling good. It’s finally out there and that does feel good.

To your point about trying to function during the pandemic, how have you been holding up? We’re nearly a year into this thing, which is wild. How has it been for you, particularly with how it’s affected the music industry?

It’s been very challenging. Like many people, my job disappeared, and my income took a big hit. So I’ve been figuring that out. But, for me personally, it’s a great blessing, because my job was to travel and travel and travel and keep traveling. Touring and playing live music is my bread and butter; it’s how I support my family, and a lot of other people. I work with a lot of people whose livelihoods depend on me going and going.

So I’ve been in this position for years now where I’ve been petitioning my team for a year off. I’ve felt like I need to step back from this endless touring, which I’ve rarely done in my life. Since I’ve started I’ve always not stopped… Then, boom. You get permission to stay home with your kids. That’s been an incredible blessing.

What did the early moments of inspiration and early songwriting sessions for Revolutionary Love look like for you?

A lot of these songs on this record were written just about a year ago, on my last tour. Of my life [laughs]. We were going up the West Coast last February… Most of my writing since the advent of my children 13 years ago comes on tour, because when I come home to my kids they just eat my head. They consume my head. And there’s nothing left for myself, for my guitar, for my muse. As any parent can probably relate, when I go on tour now it’s vacation…

So I was out on tour doing what I do, the last bunch of years, which is songwriting boot camp. So I was writing a lot of songs on this record… Two of the songs on the record preceded my writing my memoir [No Walls and the Recurring Dream]. I wrote “Chloroform” and “Metropolis” and then I sat down and tried to write a book. That consumed me. I was not able to write songs and write a book and wear all the other hats. So there was about a two-year break in writing songs, which is completely unique for me.

That sounds like quite a fruitful time, and like you were juggling a lot at once. Although that seems like something you’re used to doing at this point.

I do think the record is cohesive, because after this start-stop, wait a couple years… the actual recording of the record was of a moment. When it finally came down to documenting these songs and making this record, I spent two days tracking the songs with a drummer. Then we overdubbed another three days with the other musicians. There was a lot of immediacy. I think all of the disjointedness of it was erased by this very performative act of recording.

As I’ve spent time with the album, it’s hard for me not to hear resonance with much of what’s gone on in the last few months, which would obviously have occurred after you wrote the songs. Given that you’ve been revisiting the songs as you prepare for your release show, have you experienced that feeling yourself?

Pretty much every time, with every record, which has become increasingly fascinating to me over the course of my songwriting life. To my mind, it reveals so many deep and mysterious things. When the quantum physicists say, “Time is not linear,” I really do experience that, as an artist. When you are sort of tapping into whatever it is, if you are blessed in some way with an ability, when you get into the zone, whatever your zone is and you supersede your limited consciousness — something is fueling you, coming through you, that is bigger than you — then it is not of time. The future and past are just artifacts of our limited perception.

I’ve found so often over the course of 30 years that I write a song and it’s like, “What is that about?” Then six months or a year later, “Oh, that’s what that’s about.” I felt it coming. I don’t think I’m special in that way, or unique. I think we have a deep level of consciousness that we’re rarely able to access.

In reading to get ready to talk with you, there was a quotation from you that stuck with me; I believe it was in reference to the title, Revolutionary Love. You said, “It’s about carrying the energy of love and compassion into the center of our social movements and making it the driving force.” There are certainly forces like that at work right now — perhaps not as many as we’d like — but how do you see compassion at work in the world right now? And as you look to the end of the pandemic, whenever that is, how do you hope it will have grown?

I hope we collectively rebound from this culture of division and hate and “us” and “them” — these incredible wedges that have been driven into families, let alone communities, let alone our nation. I hope that collectively, and I suspect I’m not the only one, [that] we can use this as fuel to slay that beast, to finally dedicate ourselves to the work of unity, to the work of seeing ourselves in community, not as warring factions or “rugged individuals” or whatever [drives] these American myths and lies and the calculated propaganda that keeps us fighting each other against our own self-interests.

Will this be the breaking point? Will we really recognize each other as family, with different uniforms, or skin, or cultural aspects? Can we see through this, finally, and become this thing that America has been aching to become? I really hope so. There are so many people out there doing this work of community, of compassion. It’s all or none. You cannot succeed, you cannot transcend, you cannot be successful if you’re pushing other people down to do so. … When you step into that place of [politicians saying], “Let’s come together”… those who have been struggling for so long for basic civil rights, women included, it’s hard to take those words at face value. “Come together? Okay, when your boot’s off my neck.”

You have a collaborative and creative friendship with Valarie Kaur, and she provided some inspiration as you were crafting the album. What is it about her that makes her a kindred creative spirit for you?

After Trump’s installation by the Electoral College in 2016, I was reeling. We were all reeling. Somebody sent me a speech that Valarie gave on New Year’s Eve. So this is post-election, pre-inauguration of the Cheeto. Somebody sent me this speech she gave and here she is, in an African-American church in D.C. and there are all of these faith leaders, these powerful ministers — you can just feel this community of power and faith. And Valarie steps in and she speaks from her perspective. She is a Sikh American and she speaks from her faith, and she speaks to the moment so powerfully.

My friend sent me this knowing I’d appreciate it, and I said to myself, “I need to get in touch with this woman.” And I did. I found Valarie and lo and behold, she says, “I’m a huge fan. I’ve loved you since college.” So we were fans of each other. We just became allies. She has come and stayed with me. She was part of my BabeFest last year in New Orleans. I gave her feedback on her book when she was writing it, and vice versa. We are deeply kindred in our work and our coming together as friends felt like the universe brought us to each other so we could support each other.

One track I’d love to dig into is “Do or Die.” The arrangement has such a great groove and gets caught in your head. And it has a message that is inspiring but also incisive, which seems like it would be a difficult balance to strike when writing a song. How did you write that one?

What you’re reflecting back is what I’m talking about in terms of my goal as a writer these days: can I be no less incisive but have the light of hope, the light of possibility, shine through? I look back at some older songs of, say, the Bush era, and there are a lot of laments. It was the heaviness of the violence and the oppression and the wrongness. I thought that was as bad as it gets but lo and behold, he’s a good guy now! It’s really incredible how Trump has unified most of the rest of us. But that refrain of “Do or die / we can do this if we try,” I think that sentiment pervades the whole record. It’s like, “Oh, God, it’s hard. Oh, God, it’s dark out there. Do you ever want to just give up? Me too.” But I’m going to wake up tomorrow and do it anyway. This is the good work of the world. Joining all of the many people who do it is really the only thing I’ve got.

You mentioned earlier in our conversation that the recording experience you had was positive, possibly even cathartic. Tell me more about those few days you spent recording, and with such a great group of musicians.

I would say that the process of the record began when I showed up at the Eaux Claires Hiver festival in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. They do these epic gatherings. Somebody must just invest a lot of money and let it go. I was invited to a week-long gathering with many, many artists, tons of musicians, dancers, writers, photographers, designers, and it was all room and board paid, free beer at night, just have fun. … I showed up with ‘Valarie wants songs’ in my back pocket. Valarie said, ‘Ani, write me songs.’… It was very inspirational, being surrounded by this ad hoc community of artists. I met this wonderful producer, Brad Cook. … Then when I had a new album’s worth of songs and suddenly we’re in lockdown, it was all seeming suddenly not plausible.

I was thinking, “I want to make a record now. Damn it, what are we going to do?” I talked to Brad and he was like, “Listen, if you will get on a plane and fly to North Carolina, I’ll put a band together. We’ll track the songs.” So I just trusted this dude that I barely knew and I said, “This is all I got. I’m coming.” I came a week later. All his homies in Durham were on lockdown, so they were all home. And they’re all incredibly talented people, there in them hills.

You have several new projects in the works, like your radio station and your children’s book. As you look ahead to the coming months, what are you looking forward to and what can we expect to see from you?

Beyond the book and the radio programming, which is always expanding, I’m also working on a musical centered on restorative justice. It’s an alternative to our current justice system. It’s a different idea about what is to be done when violence occurs. I believe in it very deeply. I have been aware of the profound potential of restorative justice to actually end cycles of violence. I think mass incarceration, “tough on crime,” capital punishment — these are all continuations of cycles of violence. This isn’t healing. …

This musical I’m working on is centered on the story of my friend Lester Polk, who is in prison for life for a violent crime committed many years ago. Ten years after the crime he was brave enough to get together with one of the survivors of his crime — of course, this woman, the survivor, was an incredibly brave and powerful woman. … I feel that in Lester’s story is also a template for our whole society. There has been great violence committed. There are deep wounds that must be attended to. How do we do that?

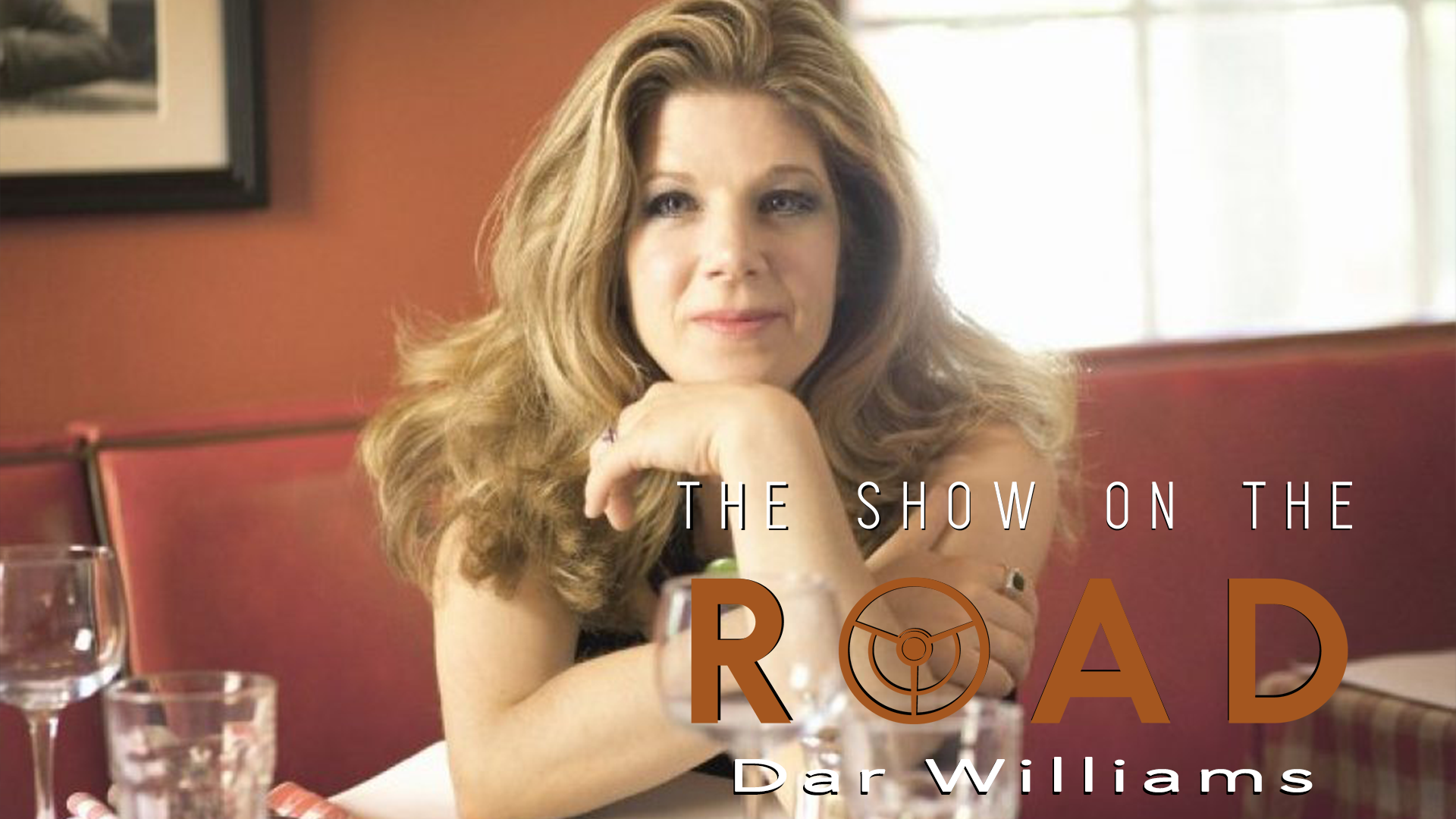

Photo Credit: Daymon Gardner