Tim O’Brien & Jan Fabricius‘ new album, Paper Flowers, represents something of a double collaboration. While O’Brien has achieved many accomplishments in his long career, Paper Flowers stands as his first official album collaboration with his wife, Jan, although she has written and performed with him over the past decade.

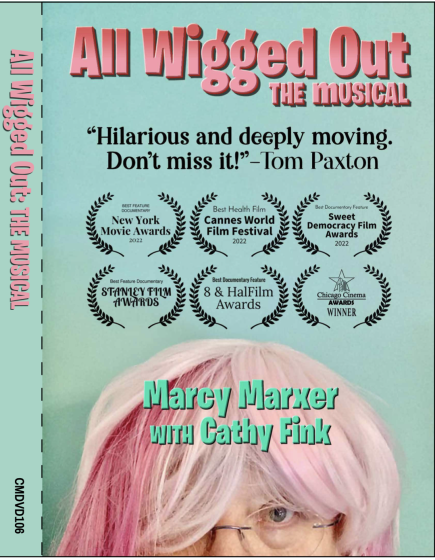

Secondly, Paper Flowers is the result of the couple’s ongoing collaboration with the legendary singer-songwriter Tom Paxton. Twelve of the album’s 15 songs are the product of these regular Zoom sessions. Paxton had known the couple for years from traveling in similar musical circles, but their virtual songwriting dates arose after mutual friends Cathy Fink and Jon Weisberger asked O’Brien and Fabricius if they would consider co-writing a song with Paxton for the Bluegrass Sings Paxton project that they were then just getting off the ground.

The first song the three of them wrote together, “You Took Me In,” wound up on that 2024 release. “We wrote the song really quickly and we’re really happy about it,” O’Brien shared on a phone call between concerts with Fabricius in New Mexico. “It did jump start the process.”

O’Brien has found this collaborative process particularly productive. “Writing songs on your own, for me, sometimes I labor over them for months,” he elaborates. “But with a co-write, it seems like your time is precious. The idea that you’re together in the same space…and you want to get to the crux really as quickly as possible. And in general, it’s a liberating process. It’s like fishing. You’re pulling these things out of the water and you see, ‘Oh, there’s a good one. Here’s a good, good size one.’”

You can easily sense the musical liberation on Paper Flowers. The album stands as perhaps O’Brien’s most musically diverse work across his celebrated career. While still securely rooted in an acoustic foundation, the record contains a variety of music styles, including the boogie-woogie jaunt “Blacktop Rag Top,” the gospel-tinged “Back To Eden,” and the New Wave-y rocker “Down to Burn.” Fabricius discovered that these songwriting sessions can lead to some interesting results.

“It amazes me how we’ll have an idea and then by the time the whole song’s molded and done, it may be totally different, take you down a different path than you thought you were going,” she says. One example of this twisty path of songwriting came when the couple shared with Paxton the story of an armadillo that they were battling in the yard of their Nashville home – including the animal’s miraculous escape from a raccoon trap. Paxton, who was at a laundromat at the time, immediately saw it as a song premise. The highly comical “Lonesome Armadillo” relates the misadventures of an armadillo that’s stranded in a laundromat. It’s trying to bum a quarter to get back to Amarillo after failed attempts to become a Nashville music star, including getting kicked out of the Ernest Tubb Record Shop and not getting to meet award-winning bassist (and longtime O’Brien collaborator) Mike Bub.

Fabricius also credits Paxton for coming up with a key lyrical detail – a peanut butter sandwich – in “Covenant,” a heartbreaking song about parents losing a child in a school shooting that was inspired by the 2023 Covenant School tragedy in Nashville. She recalls, “When he said, ‘Well, let’s say this kid has got a peanut butter sandwich in the backpack,’ at first I thought: ‘Huh?’ And then I thought, ‘Oh boy, that really does bring the reality to it.’ We’re just putting ourselves into the parents’ shoes a little bit, you know, and what can you say? It’s hard to put the words to it, so less was more.” O’Brien adds that these “visual references and physical details are sometimes better than trying to moralize or anything.” He also drew a parallel to the subtleties involved in cooking: “If you make cornbread, you don’t want to stir it up too much. It doesn’t work as well if you stir it up too much.”

Detailed lyric writing is something Paxton very much believes in. “It’s not just a tree; it’s an oak tree,” Paxton believes. “It’s not just a street, it’s Cornwall Street. You get them closer to life when you notice the particulars of life and the sandwich in the kid’s backpack is a given and it’s up to you to see it.”

The importance of details also was central in the creation of the track, “Yellow Hat.” Paxton came to one session stating that he wanted to write a song about a hat. Not just any hat, but a yellow hat. This sense of specificity certainly lent an air of realism to the tune, which deals with a couple aging gracefully. The lyrics come off as being so relatable and authentic that people think it is about O’Brien and Fabricius. O’Brien says that he has alerted audiences that it is not them in the song by announcing: “This is about an old couple, not us; (they’re) moving out of their house, not our house.”

“He hasn’t bought me a yellow hat!” Fabricius chimes in.

Paxton, in fact, often arrives to the Zoom with a premise or a phrase that he is eager to work on. Fabricius recalls him saying: “’This idea has been driving me nuts all week. It’s about a guy who really loves his wife but all he does is complain about her.’ And we were off and running.” After coming up with lyrics for this premise, O’Brien and Fabricius realized the next day that the song was very husband-sided, so they wrote a verse from the wife’s perspective. “And (Tom) was really happy with it,” Fabricius reveals. And well, he should be. The tune, “This Gal Of Mine” sits nicely with Tennessee Ernie Ford/Kay Starr’s “You’re My Sugar” and John Prine/Iris Dement’s “In Spite Of Ourselves” as a classic battling couples country tune.

There are times too when ideas come out of nowhere – or close to nowhere. At one of their virtual meetups, O’Brien was sitting around riffing on the guitar and, as he recalls, “Tom says, ‘Boy, the more you play that, the more it sounds like you’re playing ‘fat pile of puppies.’” And thus, the song “Fat Pile of Puppies” was born. While the tune may initially sound like a light romp simply about adorable little dogs, “Fat Pile of Puppies” (at one time considered for the album’s title) holds a deceptive depth to it. The crucial lyric “Falling in love is what I fear” could easily be describing the emotions for another human as much as for a dog.

“It’s kind of a love song in a way,” Fabricius confides. The writing of this song also came as O’Brien and she were still mourning the loss of their 17-year-old dog; however, they have since acquired a new pup named Nellie Kane (yes, after the O’Brien-penned Hot Rize track).

Real-life inspirations serve as the source for several other songs on this album. “Father of the Bride,” for example, was written for Fabricius’ son when his daughter was getting married. The humorous “Atchison” was inspired by a trip the couple took to Kansas, where Fabricius is from. She has a cousin who actually lives in Atchison, and during the visit, O’Brien exclaimed: “I have never been to Atchison.” The phrase stuck in their heads, giving rise to the album’s catchy lead-off track, which not only references the great train tune “On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe,” but also affords O’Brien the opportunity to break out a Jimmie Rodgers-like yodel.

It’s not surprising, however, that the couple wound up choosing “Paper Flowers” as their title track, because it serves as something like their courting song. The tune came about after they came across O’Brien’s old notebooks (the “little $2 notebooks you could put in your shirt pocket,” as he described them) in which he had written his early love notes to her. Fabricius saved the postcards and paper flowers that he had sent her. One of the notes contained the sentence: “one for you and one for me and one for the miles in between,” which got transformed into one of the song’s key lines.

“We still have the paper flowers on the mantle,” Fabricius shares. “And they made for good cover art.”

The tracks that the couple wrote without Paxton, “I Look Good in Blue” and “Down to Burn,” are both true stories, although not drawn from their own lives. “I Look Good in Blue” is a gin-soaked portrait of a honky-tonk piano player whose family told O’Brien and Fabricius about this woman whose wish was to “save that (Bombay) Sapphire bottle and pour my ashes in.” Another song drenched in alcohol, “Down to Burn” was written after the couple encountered a quintet of drunk women on a “girlfriends’ getaway.” The tune, which exudes an ’80s New Wave party vibe, provided O’Brien the chance to dust off his electric guitars. “The great part is seeing Tim in our music room putting electric guitar on (the song). He had more fun with that,” Fabricius shares. O’Brien admits, “I sweated over it more than I had fun. I did enjoy that. I have several electric guitars, and I don’t know how to operate them, and it made me try to learn more. I kind of got a couple of them working pretty good.”

O’Brien has won two GRAMMYs and made a lot of music in his over 50 years as a professional musician. Toward the end of our conversation, he shared some of his thoughts about the role of music and musicians in society. “The music is, in a broader sense, like the human song. It’s like creative force, like a tree growing or grass growing. It’s going to happen and we’re the vehicles – the musicians – the people who play music and we just organize it in some way to let it be there…

“The human race could not function without music,” he continues. “It’s used for various things. It’s used for ceremony. It’s used for dancing. It’s used for entertainment. It’s used for communication… I mean Bob Dylan, he wrote ‘Blowing in the Wind.’ He was writing what he saw, what was already going on. It wasn’t like he invented that. He’s the channel.” O’Brien then paused before adding, “It’s a nice thing to be in the channel and kind of push it along.”

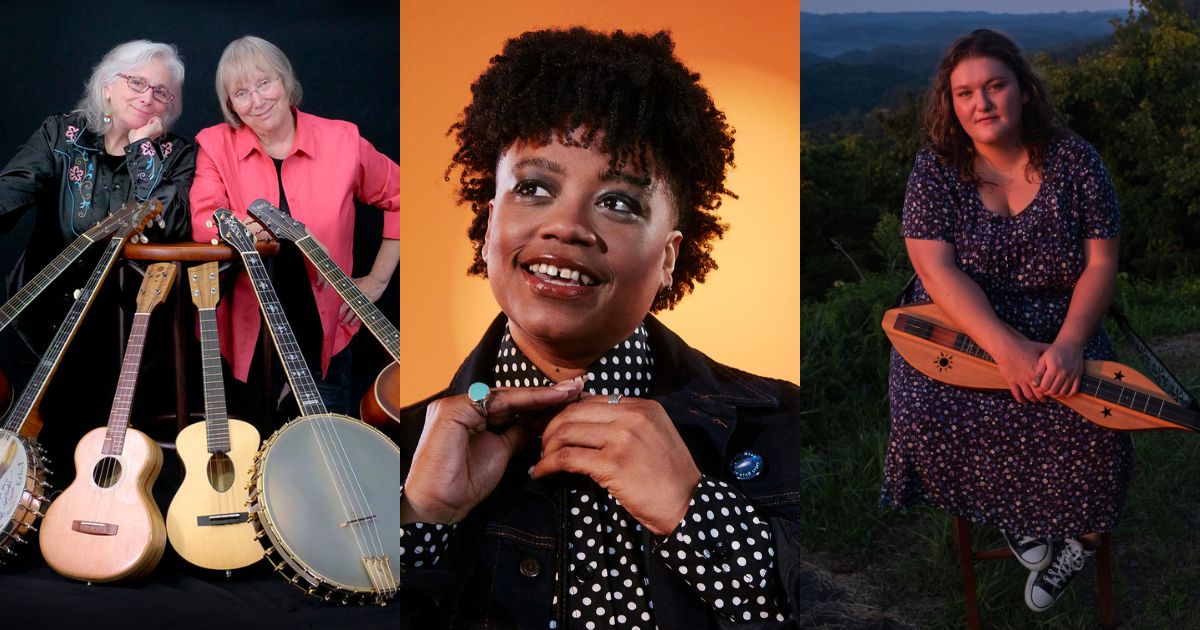

Photo Credit: Scott Simontacchi