Though it’s not that hard to find some who will argue the point, bluegrass is widely held to have originated when banjo phenom Earl Scruggs joined Grand Ole Opry star Bill Monroe’s band in early December, 1945. Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys — the possessive wasn’t just there for show — were already among the anchors of the radio show’s cast, but contemporary accounts (and a handful of bootleg recordings) make clear that, to the ears of an almost instantly enraptured audience, Scruggs’ rapid-fire banjo playing elevated the group’s sound to a new level.

Almost instantly, groups sprang up — or reoriented themselves — in pursuit of the new sound, and although banjo players and fiddlers were the most obvious converts, the truth is that virtually all of the intricacies the band brought to their sound were soon emulated. By the time Scruggs and guitarist/lead singer Lester Flatt left the Blue Grass Boys at the beginning of 1948, the quintet’s live performances and a handful of recordings had already inspired some notable followers, who, out of artistic desire and commercial necessity, quickly busied themselves in developing their own distinctive takes on the sound of the “original bluegrass band.”

As we near the 75th anniversary of this foundational origin story, BGS will be looking back across the sweep of those years — and first up, of course, a clutch of true pioneers that share a common accomplishment: they are the acts honored by induction into the IBMA’s Hall of Fame in its first five years and their plaques proudly hang at the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky.

Bill Monroe (inducted 1991)

A complex personality with a skill set that included equal measures of innovation and synthesis, the mandolin-playing Monroe (b. 1911) moved from a mid-1930s duo with his brother to assembling a hot string band during World War II to fronting that original bluegrass band — an achievement which earned him his “Father of Bluegrass” title. Though it’s easy to discern the elements he brought together in that music — old fiddle tunes; Scotch-Irish ballads; African-American blues, jazz and gospel; western swing and more — his creativity extended beyond simply stirring them together and kept him a central figure from its inception until his death in 1996.

Indeed, while his early classics are essential to the bluegrass canon, even his late-life instrumental compositions have enjoyed a growing influence among today’s hottest young players. In fact, he collected his first Grammy for 1988’s “Southern Flavor.” Monroe was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1970, and as the composer of “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” he joined the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1971, received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys in 1993, and entered the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as an early influence in 1997.

Representative tracks: “Blue Yodel No. 4,” “I’m Going Back to Old Kentucky,” “Lord Protect My Soul,” “Midnight on the Stormy Deep,” “Southern Flavor”

Earl Scruggs (inducted 1991)

Though he wasn’t yet 22 years old when he joined Monroe’s band at the end of 1945, Earl Scruggs (b. 1924) was ready to step into the spotlight, and, with the exception of a stretch of ill health in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, he never relinquished it until his death in 2012. Unlike many instrumentalists who change their approach according to musical context, Scruggs believed that his picking style — built around right-hand patterns called “rolls” — could fit anywhere, and after his groundbreaking years with Monroe and then Lester Flatt, his career seemed devoted to proving the point.

Having created much of the musical vocabulary for bluegrass banjo picking, he moved on to playing with his sons in the Earl Scruggs Revue, a country-rock-bluegrass fusion band that was arguably more successful — at least in commercial terms — than Flatt & Scruggs had ever been. In the 21st century, Scruggs championed a broad variety of younger musicians while continuing to play those same sweet rolls he’d created as a young man. He was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Grammys in 2008.

Representative tracks: “Blue Ridge Cabin Home” (Flatt & Scruggs), “Foggy Mountain Chimes” (Flatt & Scruggs), “Travelin’ Prayer” (Earl Scruggs Revue), “The Engineers Don’t Wave From the Trains Anymore” (with Tom T. Hall), “The Angels” (with Melissa Etheridge)

Lester Flatt (inducted 1991)

With an expressive, emotive voice and an impressive array of demeanors that ranged from dry and sly to devout and down-home, rhythm guitarist Lester Flatt (b. 1914) was the perfect musical complement to Earl Scruggs, and their 1948-1969 output was at least as influential as Monroe’s. Flatt & Scruggs won a 1968 Grammy for their classic recording of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.”

But where Scruggs was not only interested in playing with his sons, but also interested in putting his banjo into a wider range of contexts, Flatt preferred sticking to the country side of bluegrass. In the aftermath of their breakup, Flatt’s drawl deepened and slowed as he presided over a series of gifted lineups that included peers like Josh Graves and Vassar Clements, alongside young up-and-comers from banjoist Kenny Ingram to a teenaged Marty Stuart. Flatt & Scruggs were inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1985.

Representative tracks: “I’ll Never Love Another” (Flatt & Scruggs), “I’ll Go Stepping Too” (Flatt & Scruggs), “On My Mind” (Flatt & Scruggs), “You Are My Flower” (Flatt & Scruggs), “Gonna Have Myself a Ball”

The Stanley Brothers (inducted 1992)

The career of Ralph Stanley (b. 1927) and Carter Stanley (b.1925) illustrates both the profound impact that the original bluegrass band had on their peers, as well as the complementary artistic and commercial drives that impelled those successors to create their own unique style. In their first recordings, made while Flatt and Scruggs were still Blue Grass Boys, you can hear the Virginia-born Stanley brothers revamp their old-time string band approach into an approximation of the pioneers’ sound, yet within a matter of months, they had found a compelling variant.

The Stanley sound was built in part around Ralph’s stolid but driving banjo and soulful tenor singing, but even more around Carter’s mournful lead vocals and powerful songs. Over the years, while they moved from the Nashville-based Columbia and Mercury labels to scrappy (and multi-racial) Cincinnati indie, King, their sound became even more recognizable, as owner Syd Nathan hectored them into de-emphasizing the fiddle and leaning more into the innovative work of flatpicking lead guitarists like George Shuffler. The brothers’ partnership came to an end in late 1966 with the early, alcohol-related death of Carter; Ralph would continue on with his own twist on the Stanley Brothers’ sound until his death in 2016.

Representative tracks: “The Lonesome River,” “Our Last Goodbye,” “Let Me Walk, Lord, By Your Side,” “I’ll Just Go Away,” “Pig in a Pen”

Reno & Smiley (inducted 1992)

The first banjo player to follow Scruggs, albeit briefly, in the Blue Grass Boys, Don Reno (b. 1926) deliberately sought to create a distinct and instantly recognizable style of his own on the instrument. By the time his partnership with singer-guitarist Red Smiley (b. 1925) had settled into regular recording for King Records in the early 1950s, he had succeeded completely, and for good measure had done the same with flatpicked guitar solos, too. As Grand Ole Opry announcer Eddie Stubbs once put it, Reno & Smiley were a country band with a banjo instead of a steel guitar.

Though Reno could and sometimes would blister a banjo solo, many of the band’s signature numbers were heart songs, country shuffles, earnest gospel outings and more, including occasional flashes of rockabilly and jazz. Reno wrote many of them, sang tenor and occasional leads, and shared the instrumental limelight with their steady fiddler, Mack Magaha, and occasionally with one or another mandolin player, including his son, Ronnie. The partners split for a few years in the mid-‘60s, then reunited for a brief period before Smiley’s death in 1972. Reno continued to record and perform with partners ranging from Bill Harrell to his sons until he passed away in 1984.

Representative tracks: “I’m Using My Bible for a Roadmap,” “I Know You’re Married,” “Little Rock Getaway,” “Please Remember That I Love You,” “Just About Then”

Jim & Jesse (inducted 1993)

Though Jim McReynolds (b. 1927) and Jesse McReynolds (b. 1929) were born just a few dozen miles from the Stanley Brothers, the music of Jim & Jesse could hardly have been a more different kind of bluegrass. The duo’s singing was smooth and refined — especially guitarist Jim’s silvery tenor — while the instrumental sound was driven by Jesse’s innovative mandolin cross-picking and their overall approach by the latter’s eclectic tastes and influences (he appeared, for instance, on The Doors’ 1969 album, The Soft Parade).

The brothers were comfortable in reaching for a more countrified sound, helped by banjo players like Allen Shelton and Carl Jackson, who were adept at playing radio-friendly licks on a dobro-banjo as well as ‘grassier fare when that was called for. Smart businessmen as well, the duo were among the first to appear on television in the early 1950s, recorded an entire album of Chuck Berry songs in the mid-1960s, started their own label in the early 1970s, and remained a popular fixture on the Grand Ole Opry until Jim’s death on the last day of 2002. As of this writing, Jesse McReynolds continues to perform — and to innovate, too, with releases like a 2010 Songs of the Grateful Dead collection.

Representative tracks: “Pardon Me,” “Are You Missing Me,” “She Left Me Standing on the Mountain,” “Cotton Mill Man,” “Memphis”

Mac Wiseman (inducted 1993)

Nicknamed “The Voice With a Heart,” Virginia’s Mac Wiseman (b. 1925) was a founding member of Flatt & Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys in 1948, but soon left to join Monroe (and Don Reno) in the Blue Grass Boys. By the early 1950s, he’d started his own career, recording for Gallatin, Tennessee’s Dot Records — and then going to work for the label. A consummate professional, he also served as a musicians’ union official for a time, and was a founding member of the Country Music Association. He frequently recorded material other than bluegrass, especially when rock ’n’ roll and the pop-country Nashville sound beckoned in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and throughout his career, he was never afraid to use a variety of instruments besides the archetypal bluegrass ones.

Still, as a performer, bluegrass was his bread and butter from the mid-1960s on, and rather than carry a band, he would recruit players from other acts (and occasionally skilled amateurs, too) and lead them on stage with a heavy guitar strum and a quick “watch me, boys!” Wiseman’s songbook included old folk numbers, songs he heard on the radio as a polio-stricken child, big band tunes, Music Row compositions and much more. In later years, he recorded several memorable projects that highlighted songs his mother had taught him and songs that told his life story, before his death in 2019.

Representative tracks: “I Still Write Your Name in the Sand,” “I Wonder How the Old Folks Are at Home,” “Mother Knows Best,” “My Little Home in Tennessee,” “’Tis Sweet to Be Remembered”

The Osborne Brothers (inducted 1994)

Bobby Osborne (b. 1931) and Sonny Osborne (b. 1937) were among the first of what might be called “semi-second generation” bluegrass artists; unlike those who preceded them in the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, neither had performed professionally before 1950. By 1954, though, they’d hooked up with Jimmy Martin for a memorable set of recordings, and 1956 found them signed on to MGM on their own. Together with singer-guitarist Red Allen, the Brothers — Bobby singing lead and playing mandolin, Sonny singing baritone and playing banjo — had come up with an inventive new vocal arrangement that put the spotlight pretty much on them alone.

Lest that sound too cold, it should be noted that they deserved it, for not only was Bobby a formidable lead singer and Sonny brilliant in the support role, but their fearless, try-anything (the two recorded separately with avant-garde jazz vibraphonist Gary Burton in the mid-’60s) instrumental skills were profoundly original. The Brothers joined the Grand Ole Opry and signed with Decca Records in 1964, and spent the next decade fusing bluegrass and country in a way that eventually earned them a CMA Vocal Group award. Irascible, opinionated, and both artistically and commercially successful, the Osborne Brothers were at the forefront of the music until Sonny’s 2005 retirement — and while Bobby continues to perform to this day, the influence of their duo continues to grow, too.

Representative tracks: “Once More,” “The Cuckoo Bird,” “Tennessee Hound Dog,” “Pathway of Teardrops,” “Sweethearts Again”

Jimmy Martin (inducted 1995)

East Tennessee native Jimmy Martin (b. 1927) hungered to perform with Bill Monroe as a youngster, then got his chance in 1949 when Mac Wiseman quit the Blue Grass Boys. As lead vocalist and guitarist, he helped to make some of Monroe’s most memorable recordings, then partnered in various settings with Bobby and Sonny Osborne before taking the helm of his Sunny Mountain Boys in the mid-1950s. A brash, colorful guy who could boast with the best and then back it up, Martin served in the cast of the Louisiana Hayride (alongside Elvis) and the Wheeling (W.V.) Jamboree before a growing bluegrass festival circuit threw him a lifeline in the absence of a Grand Ole Opry membership.

Among early Hall of Fame inductees, he may be considered more influential than most of his peers. Service in his Sunny Mountain Boys constituted the training ground for several generations of musicians, from banjo man J.D. Crowe to newgrass pioneer Alan Munde to Americana favorite Greg Garing — and his appearance on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s Will the Circle Be Unbroken was legendary. Martin was an unstoppable force of nature who knew exactly what he wanted from a musician, yet was unable to clearly explain it. Still, he did well enough that his records are instantly recognizable, even when you’ve never heard them before.

Representative tracks: “That’s How I Can Count on You” (with the Osborne Brothers), “Rock Hearts,” “You Don’t Know My Mind,” “Tennessee,” “Freeborn Man”

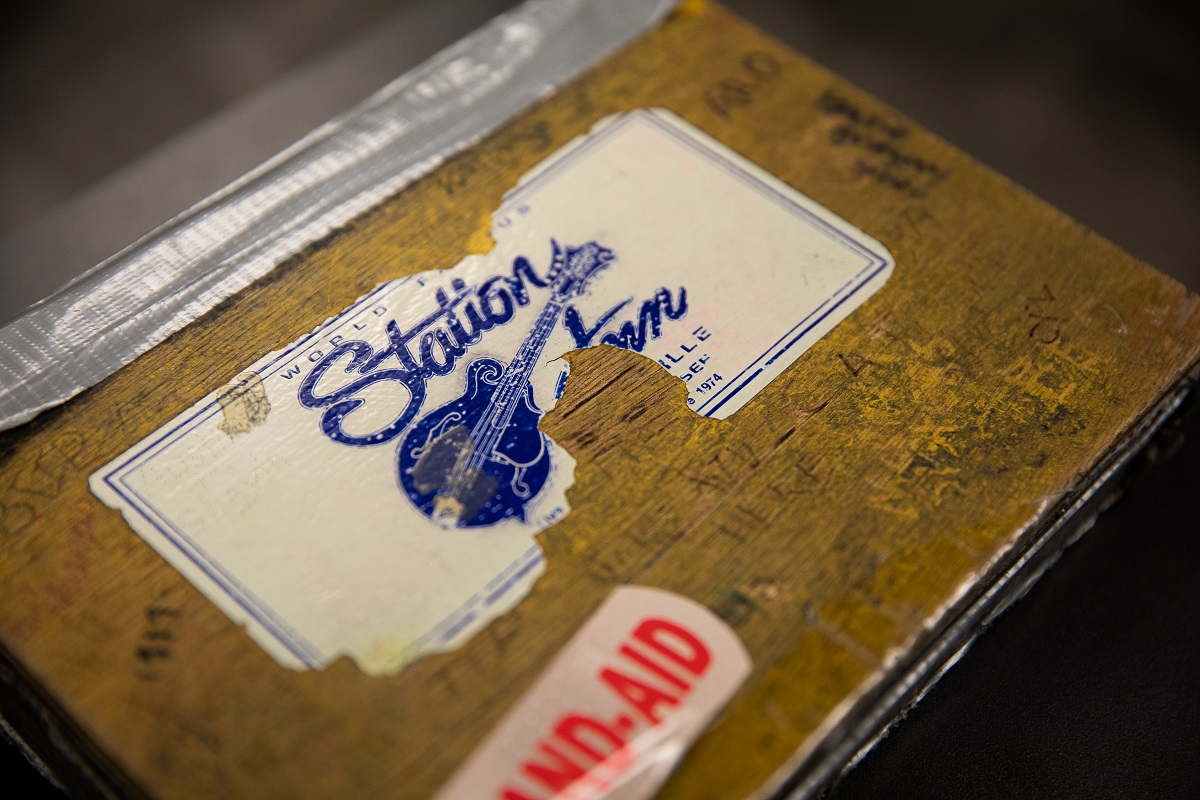

Pictured above, first row (L to R): Bill Monroe, The Osborne Brothers, Mac Wiseman, Jim & Jesse; Second row: Reno & Smiley, The Stanley Brothers, Jimmy Martin, Flatt & Scruggs