With a new generation boasting unapologetic traditional influence, there’s more classic-sounding country in the mainstream today than in many years before. With his second album, When I Write the Song, Jake Worthington captures one specific aspect of honky-tonk history better than the rest – its sense of humor.

That’s definitely not to say Worthington’s new album is a joke. Far from it. Over 14 songs, the Texas native sinks down into the depths of sorrow and lets his heart believe in miracles all the same. His love of the classic country form is just as authentic as his barrel-chested vocal twang, and with producers Jon Randall and Chuck Ainley joining his team, it gets highlighted with more sincerity than ever. But right from the opening track, Worthington walks in the footsteps of artists like Johnny Paycheck or Jerry Reed; his down-home demeanor is as country as it gets.

Meanwhile, the solo-written title track is almost alarmingly personal and Worthington welcomes Miranda Lambert, Marty Stuart, and Mae Estes as special guests on other tracks. When I Write the Song arrived on September 12 and by touring through the end of the year with both Jon Pardi and Zach Top, Worthington adds even more evidence of an ongoing trad renaissance.

Good Country spoke with Worthington about writing the way he lives and chasing honky-tonk inspiration farther than ever. Plus, he reveals a secret appreciation fans might not suspect.

For fans who don’t necessarily know, you have always been a proud purveyor of the classic country arts. I think that’s pretty fair to say. Are fans going to get more of that on this record or what?

Jake Worthington: Damn right. Yes, sir. I guess that whole narrative don’t ever really change for me. I don’t ever want to make any other kind of music. When somebody listens to a record that I am a part of or put together, I hope they can have a definitive direction to point to and say “That’s what country music sounds like.”

I think that comes across for sure. Now, it’s good timing because there’s kind of a little traditional renaissance going on in the mainstream. Do you agree with that?

Damn right. Absolutely. I’ve never been more inspired in terms of our genre than I am right now. I think a lot of people are writing and singing and recording great country music and I think that folks of all ages are wanting to hear it. Another thing, too, is I don’t think it’s a fad of any sort. I find it interesting – you hear terms like “traditional” or the whole “’90s” deal or whatever. To me, it’s just country music getting made in 2025. I think that’s really exciting, to know that’s the case. It wasn’t like that just a couple years ago.

So you don’t think it’s people cosplaying country?

I know it’s genuine for me. I can’t control what other people do, but hey, if they want to play dress up, that don’t bother me none. I think it’s good for country music. I’m glad that they’re wanting to dress like a grownup.

One thing that I’ve always loved about classic country itself, and something that you do well on this record, is to have a touch of humor. That’s not around as much anymore, but you do that well.

Well, I think it’s funny. I have always struggled with the idea that I never wanted to not be taken serious as a singer or songwriter, but I still like to have fun. I still cut up and it ain’t all rain and storms all the time. I think country music allows room for all of that. There’s definitely a couple songs on this record that is lighthearted, and I guess I was all right with that.

There’s definitely some hardcore heartbreak in here, but the reason I ask is because of the opening track, “It Ain’t the Whiskey.” There are not many songs about getting pulled over and accused of a DUI these days – even fewer that are fun.

Well, some of us write from the research department, I guess. Unfortunately, I was just trying to make light of what was a really shitty situation for me at one point in time in my life. I’ve made some dumb decisions in my adolescence, I guess. That was a good way to look back and laugh at it.

How about “Two First Names”? This one reminds me of a little bit of Joe Diffie and the way he was able to merge classic country and a funny line.

Well, shoot man, thanks. That’s just about a country girl. I’ve got a handful of women I know and love in my life that got two first names and I love that we got away with writing it without ever saying an actual name. … There wasn’t one of us that wrote that song who ain’t from the country, and we’ve all got women we love and know that got two first names. We all love a country girl.

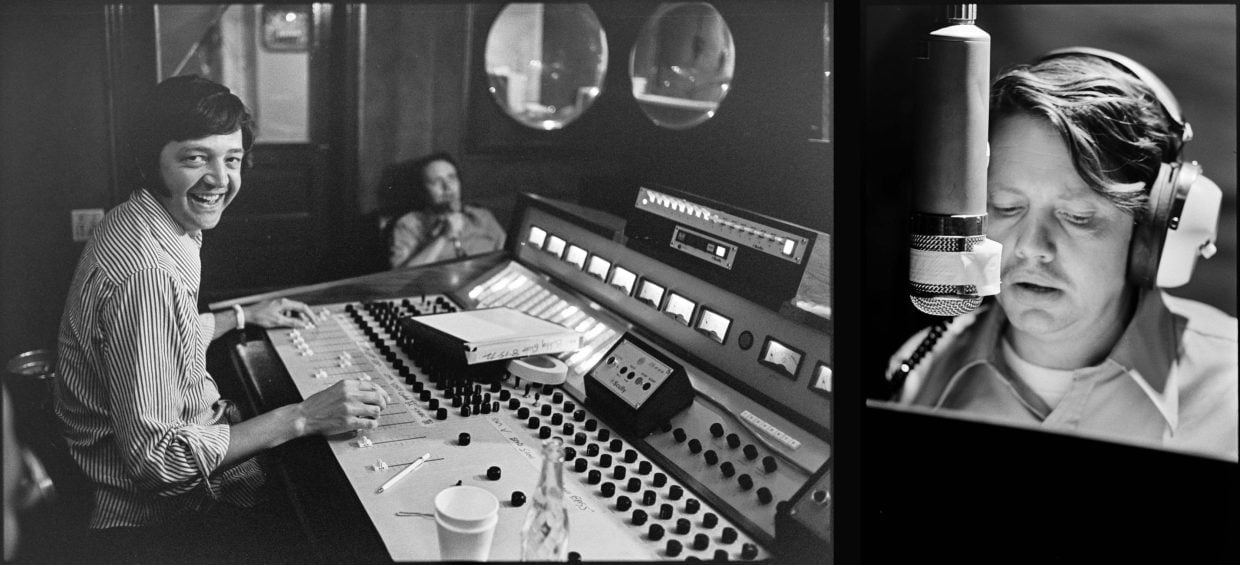

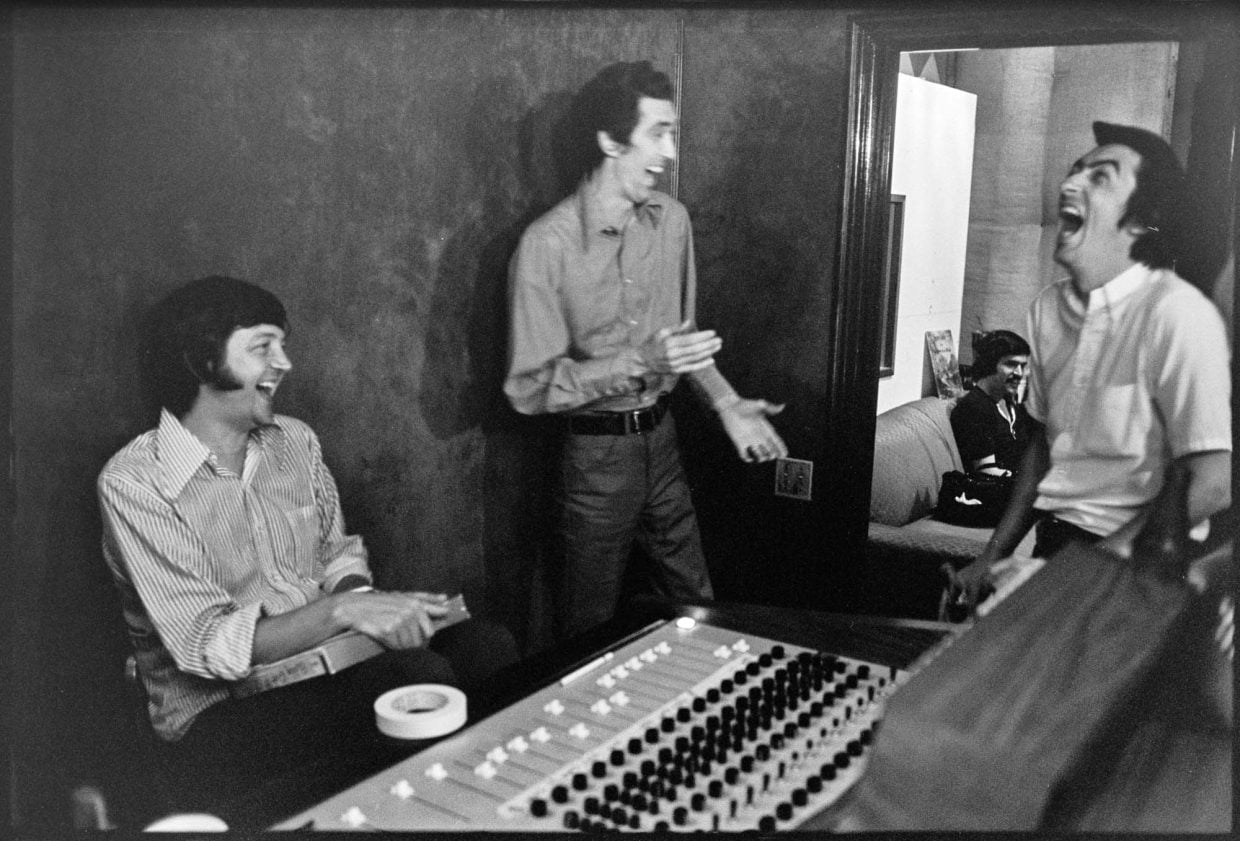

Hell yeah. Now, one thing about this record, you definitely got to work with some big names. You got Jon Randall and Chuck Ainley helping out on production, along with Joey Moi. I wonder with those two guys specifically, Jon and Chuck, did they help you move your sound or your style forward?

Definitely I think. There’s four tracks that I recorded top to bottom with Chuck and Jon … there’s a lot of really awesome things that I got to do through working with Joey. But I think for me, I wasn’t ever totally happy with the way things were ending up sonically. That was my biggest change that I was after, was just kind of where it landed sonically.

Really?

Especially with the vocal. I’m a very imperfect singer. I’m not a perfect singer. I want that to be heard. I don’t want to be masked.

Joey’s amazing, but he definitely comes from a different world sonically, right?

Yeah, and I wanted to work with guys that were making country records that inspired me. But again, I tracked nine of them songs with Joey and man, I love all of it. Chuck wound up mixing the record and Jon come in when we went to track the last four songs and it’s been a dream come true. I get to work with my heroes, man.

You also got to work with Miranda Lambert [plus Marty Stuart and Mae Estes]. Tell me about doing “Hello Shitty Day” with Miranda, it’s a cool broken-hearted waltz. Did you guys get to know each other?

Sure. I mean, I know it sounds a little simple, but she had texted me the song and I asked if I could cut it. She said yes and I said, “Would you sing on it?” And she said, “Hell yes,” so by God, that’s what we did. I don’t know, man. I wasn’t trying to get on the radio with that song. I just thought it was brilliant. I love that song.

One thing I’ve got to ask you, since this is BGS. Do you have any ties to bluegrass, or was that ever a part of what you listened to?

Where I’m from, oddly enough down there in Southeast Texas, we had to go find that stuff. There’s nooks and crannies in East Texas where these cats kinda start out in bluegrass and I think they find it through gospel music and stuff like that. But I wasn’t in the church or nothing – I was baptized in beer and I’m here to testify, you hear me?

Ha!

The great words of Kevin Fowler. But a lot of the stuff I loved the most was coming out of Ohio. When I discovered Dave Evans, that shit knocked me out.

Really?

Oh gosh. There’s something called “99 Years [Is Almost for Life].” One day I’d like to record it, but I understand that bluegrass is just as sacred as country music, so if you’re going to do it, you got to do it right and I think it starts with putting your heart and soul in it.

But I always loved Ralph Stanley. I’ve always loved Flatt & Scruggs and Bill Monroe. I mean, that might sound a little standard, but I love that stuff. Harley Allen’s one of my favorite songwriters and his daddy, Red Allen, I love the records he done. Ronnie Bowman and Lonesome River Band. I like that stuff.

Short answer – yes, sir. Hell yes. I love bluegrass.

That’s amazing. It sounds like you’re deep into it. I mean, maybe it doesn’t show up too much in what you’re doing right now, but maybe one day you ought to do a bluegrass record.

Oh, man. We’ll see, but right now all I want to do is what sounds like country music to me. I think it’s a matter of if you got electrics on it or not. It’s just soul music. It’s gotta come from the heart.

That’s a good segue because I wanted to ask you about the title track, “When I Write the Song,” and writing that solo. You were able to share your pain quite a bit. Where did that come from?

I don’t always wind up writing by myself. I think a lot of us writers sit down and try, and if we could, we would write a lot by ourselves. But that one just kind of fell out. I’d been six, seven years in [to my career] and I don’t know, I think I was a little hurt and kind of angry. I got a whole lot of, “You can’t sing that kind of music. That ain’t never going to work.” Sad songs and waltzes and whatnot. I don’t know why it’s so easy to write about the hard things or the bad things. It seems to be easier than it is to write about the good things sometimes. That’s just kind of where I was at with it.

When I wrote it, I was headed home from some gig and at the time I had been staying at my parents’. They had just got one of them push button door locks to the house with a code on it and I did not remember the damn code. There wasn’t no way I was getting in the house, so I had a guitar and a six pack of beer, a back porch, and plenty of time.

You’re kidding.

That’s what come out of that. I sat on that song for a long time. I was kind of scared of it. I wasn’t sure if it was for anybody. I wasn’t sure if it was any good. But I’m a songwriter and I think that’s just my way of showing it.

That’s real country music to me, so thank you for sharing the story. It’s funny that you got locked out – almost feels meant to be.

I’ve been locked out of a lot of things, hoss.

You’re going to be out on the road with Zach Top and Jon Pardi, right? In their own way, they both definitely inject some classic country into the mainstream, too. Are those tours a good fit for you?

Damn right, man. You tell me anywhere else, you’re going to see three steel guitars and three fiddle players in one stage. … I’m a fan of both of them guys and they know it, and I revere and respect the hell out of them. I’m grateful to get to go work with ‘em. That’s going to be a lot of band, buddy.

All right, Jake, thanks for the time, man. Let me leave you with the big picture. Just tell me what you hope people get from this record.

Well, take away a little piece of my heart while I’m giving it to you. Country music’s here to stay and I don’t think it ever left. I’m just grateful to be a little spoke in the wheels and I hope that when they hear this record, it’s something that they can go to and say, “This is what country music sounds like.”

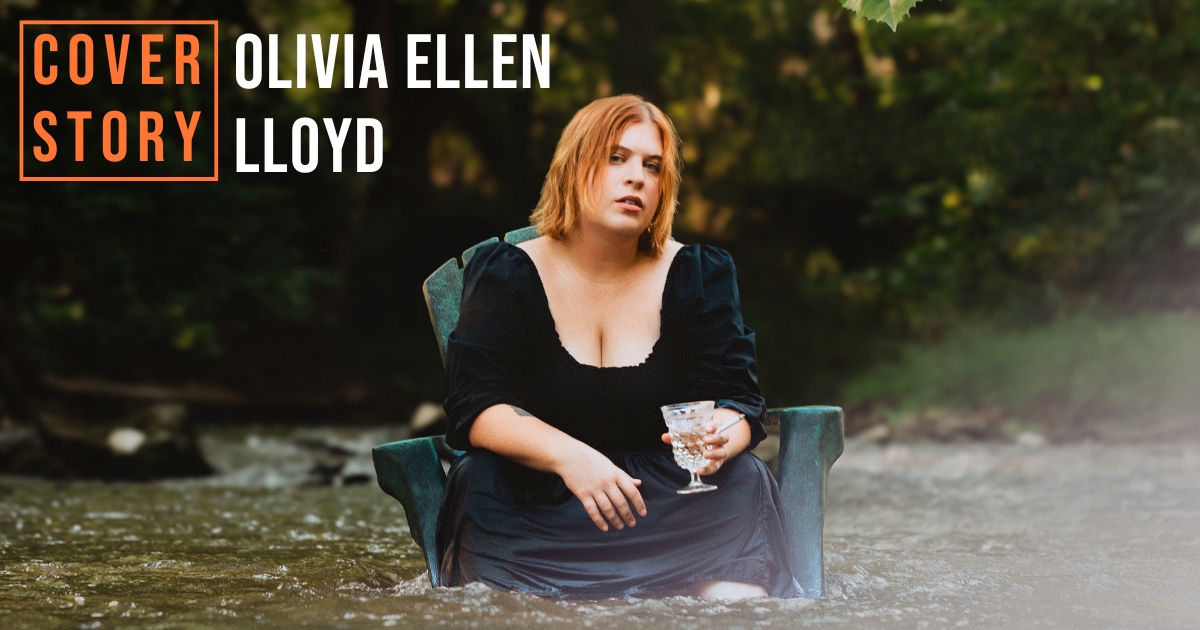

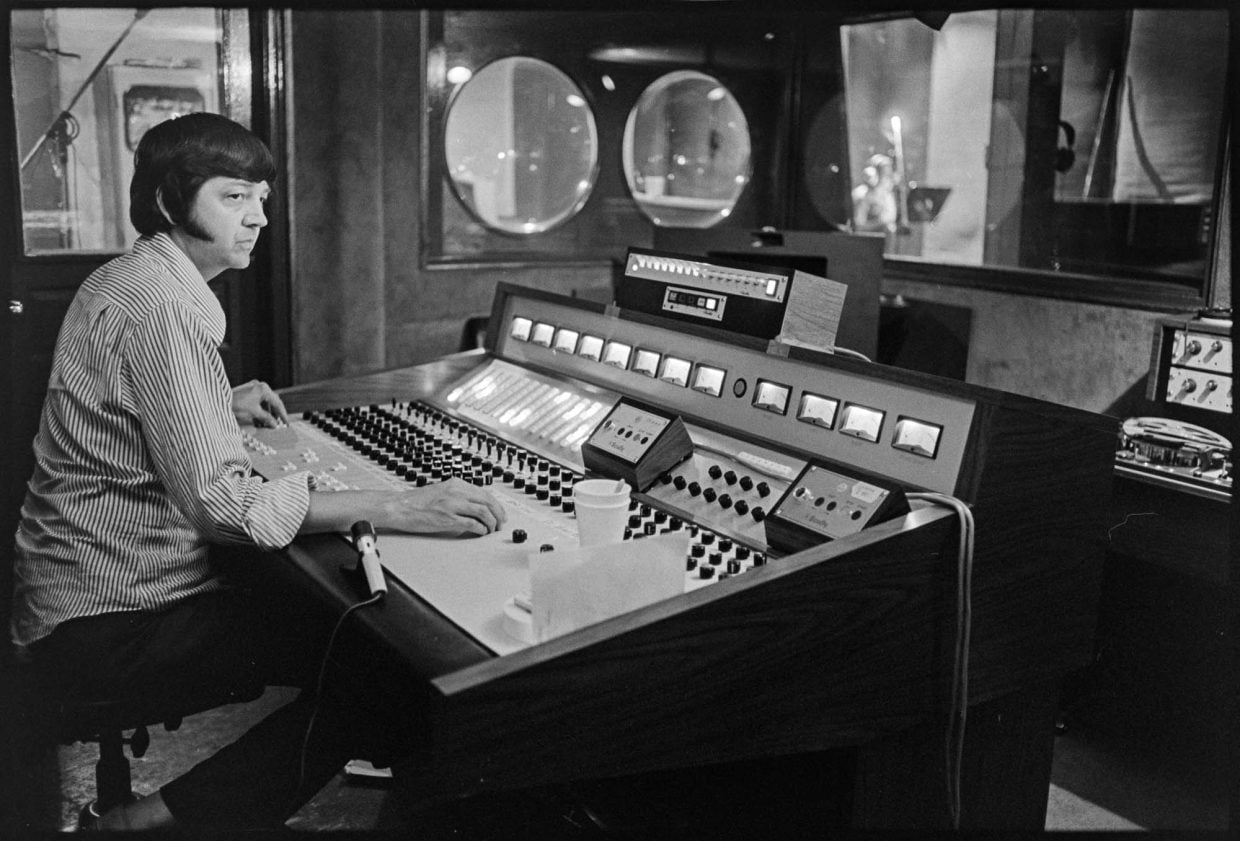

Photo Credit: Jim Wright