It’s another full week of new releases and exciting premieres! Leading off our round up this time is young fiddlin’ phenom Carson Peters singing a Bob Seger classic, “Long Twin Silver Line.” Plus, don’t miss bluegrass tracks from our friends Unspoken Tradition and Meadow Mountain – the latter of whom debuted the first installment of their SkyTheory Sessions on BGS yesterday.

There’s also plenty of Good Country to find herein! Kyle McKearney is joined by bluegrass flatpicker Trey Hensley on “Lonesome,” Jessie Wilson brings us a new one, “Outlaw,” and Will Stewart & the Gold Band share a tune from their Live in Norway project. Plus, Jordie Lane brings us a new single, too.

Yesterday, Donovan Woods exclusively premiered a new Lori McKenna and Matt Nathanson co-write on BGS,. as well so don’t miss that! It’s all below and really, You Gotta Hear This!

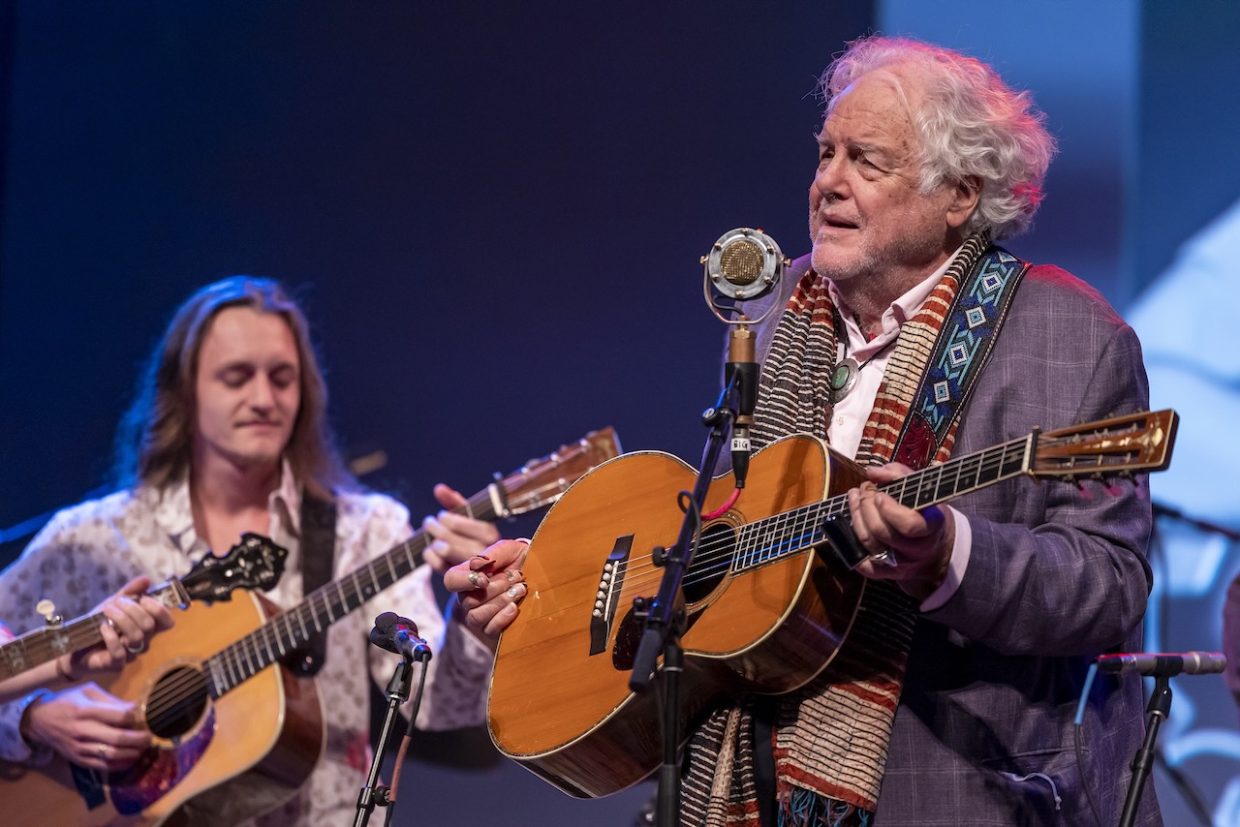

Carson Peters, “Long Twin Silver Line”

Artist: Carson Peters

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Long Twin Silver Line” (Bob Seger cover)

Album: Silver Bullet Bluegrass

Release Date: July 12, 2024

Label: Lonesome Day Records

In Their Words: “Randall Deaton approached me with this tribute project a while back, and I loved the idea and jumped at the chance to be included with the great artists that were already on board. I grew up listening to classic rock and roll music riding in my parents’ car. It definitely helped me appreciate all styles of music and I always enjoyed hearing Seger songs. Randall had most of the track ready for me when I came in to put vocals and fiddle on it, and his ideas and choices made this song even better than I imagined. We played around with arrangements for a fiddle break in the middle, but he was the brain behind the arrangement for sure. I think (and hope) that the youthfulness in my voice and aggressive style of fiddle playing suits this song well, and gives it a nice spin. I am working up a live version with my band so we can put into our shows.” – Carson Peters

Track Credits: Written and published by Bob Seger, Gear Publishing Company

Producer – Randall Deaton

Engineers – Randall Deaton, Jimmy Nutt

Tracked at Lonesome Day Recording Studio, Booneville, KY / The NuttHouse Recording Studio, Muscle Shoals, AL.

Mixed at The NuttHouse Recording Studio, Muscle Shoals, AL.

Guitar – Stephen Mougin, Gary Nichols

Mandolin – Darrell Webb

Banjo – Ned Luberecki

Bass – Mike Bub

Dobro – Jake Joines

Fiddle – Carson Peters

Harmony vocals – Sarah Borges

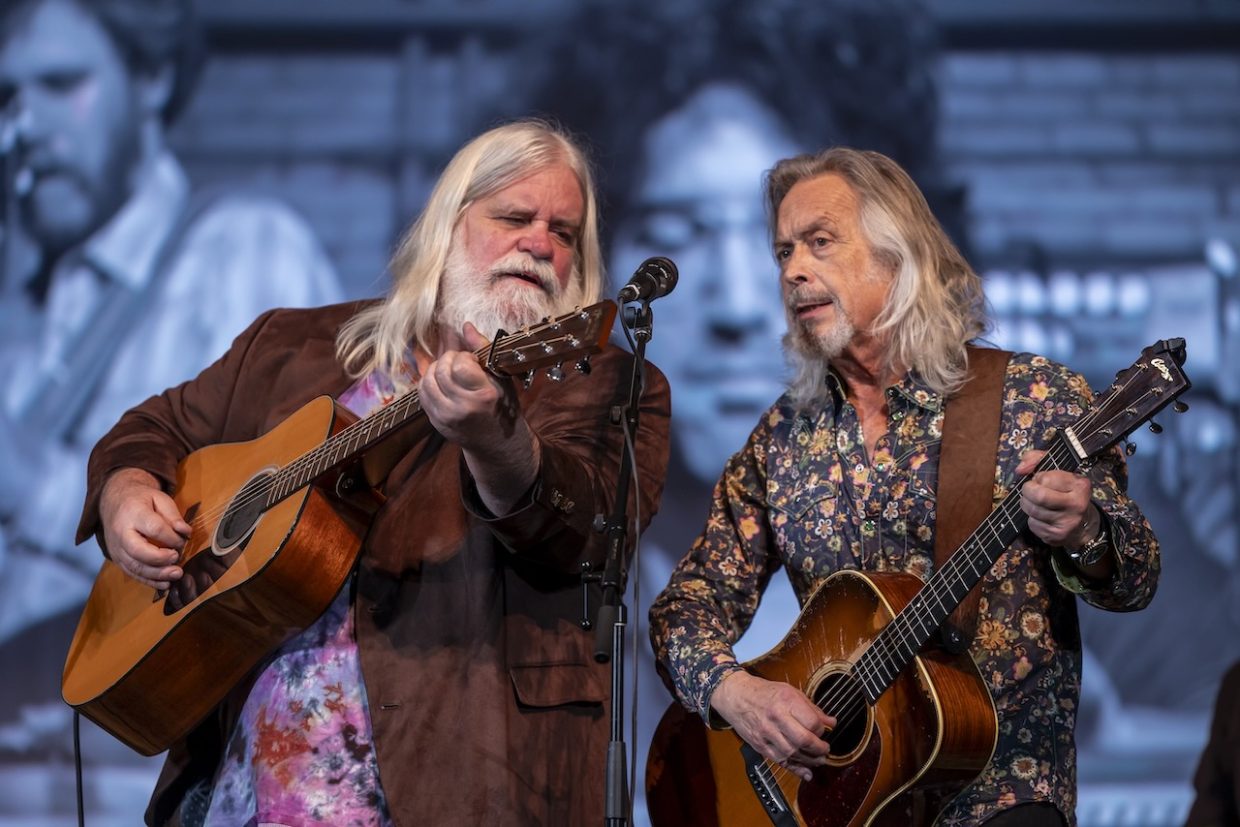

Kyle McKearney, “Lonesome” (Featuring Trey Hensley)

Artist: Kyle McKearney

Hometown: Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Song: “Lonesome” (featuring Trey Hensley)

Release Date: April 26, 2024

Label: Kyle McKearney Music

In Their Words: “I’ve been following Trey Hensley for years and have always been a huge fan of his playing, singing, and Southern charm. I got to meet Trey at a gig in Colorado and I was blown away to learn that had been a fan of mine as well. My keyboard player James and I wrote ‘Lonesome’ with Trey in mind, hoping that he’d jump on for a shred on his flattop. I love how this song turned out and am grateful to Trey and team for their contributions. I can’t wait for folks to hear this burning two stepper!” — Kyle McKearney

“I became a huge fan of Kyle McKearney the moment I heard his music several years ago. I became an even bigger fan when I got to meet him and hear him live out in Colorado last year. I knew then that I would love a chance to work on some music with him in the future. I was thrilled when the opportunity arose for me to go up to Alberta and record with Kyle for his new song ‘Lonesome.’ As soon as I heard the song, I immediately knew this was going to be a blast… and sure enough, it was an absolutely incredible experience. Kyle is such a phenomenally talented artist, and I’m beyond honored to be included on ‘Lonesome.’ I can’t wait for y’all to hear it!” — Trey Hensley

Jessie Wilson, “Outlaw”

Artist: Jessie Wilson

Hometown: Phenix City, Alabama

Song: “Outlaw”

Release Date: May 3, 2024 (single)

In Their Words: “‘Outlaw’ depicts a universal feeling – no matter what field you are in or where you’re at in life, almost everyone has felt like they weren’t good enough and wanted to fit into a certain group at some point or another. I wrote this song about Nashville; I’ve often wondered what I need to do to be wanted in this town and the music industry. Is it about dating the right person, or changing my morals – what’s the answer? This song was written from that state of mind. It took a lot of vulnerability for me to admit that there was a time when I would do anything to fit in and gain the love of others, because deep down I was so lonely and lost. It’s typical to want to compare yourself, but you have to steer your mind away from that idea. I’ve since learned that I don’t have to change who I am and that the right people and opportunities will come to me and love me for the person I am.” – Jessie Wilson

Track Credits:

Producer – David Dorn

Acoustic & electric guitar – Tim Galloway

Bass – Tim Denbo

Drums – Matt King

B3/Synthesizer – David Dorn

BGVs – Kristen Rogers and Caleb Lee Hutchinson

Recorded at Farmland Studios.

Mixing – Mark Lonsway

Mastering – Mayfield Mastering

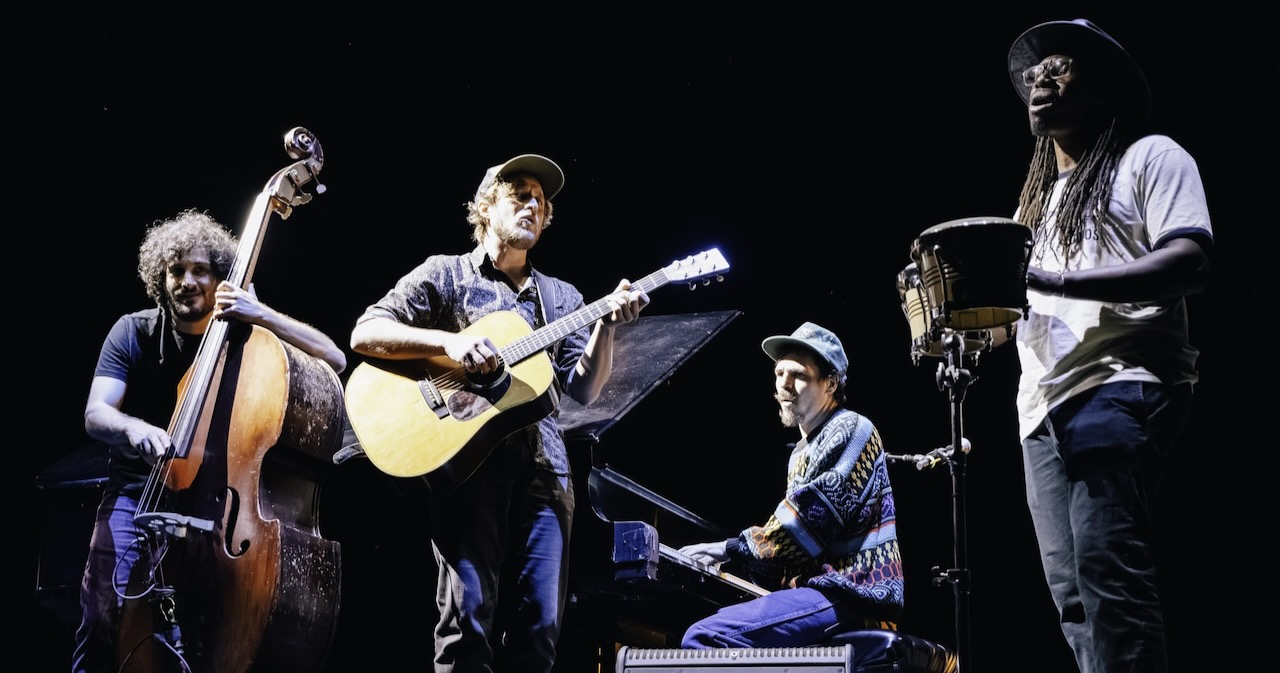

Will Stewart & The Gold Band, “Real Drag” (Live)

Artist: Will Stewart & The Gold Band

Hometown: Birmingham, Alabama

Song: “Real Drag” (Live)

Album: Will Stewart & The Gold Band Live in Norway

Release Date: June 7, 2024

Label: Cornelius Chapel Records

In Their Words: “Ross Parker, my longtime friend and bassist, sent me a rough demo of ‘Real Drag’ last year. I slightly tweaked the arrangement and melody and added a verse and it immediately became a staple in our live set. I get to throw in some jangle on this one, and Janet’s guitar playing compliments that in a nice way. The lyrics sort of speak for themselves, but it’s about a series of unfortunate events after a long night of being out, which seems to be a common theme in a lot of my songs, now that I’m thinking about it. It’s a combination of people and places that we’ve encountered over the years.” – Will Stewart

Track Credits:

Will Stewart – Guitar, vocals

Janet Simpson – Guitar, vocals

Tyler McGuire – Drums

Ross Parker – Bass

Recording Engineer – Harvard Soknes

Mixed by Brad Timko.

Mastered by Alex McCollough.

Jordie Lane, “The Changing Weather”

Artist: Jordie Lane

Hometown: Melbourne, Australia (Based in Nashville, Tennessee)

Song: “The Changing Weather”

Album: Tropical Depression

Release Date: May 2, 2024 (single); August 23, 2024 (album)

Label: Blood Thinner Records, under exclusive licence to ABC Music/The Orchard

In Their Words: “I had just got back to America after the terrible 2019-20 Australian bushfires when this massive EF-3 Tornado devastated our East Nashville neighborhood. Everything in my mind and body was kind of in shock about this severe weather, being so close to being hit. It scared the sh*t outta me. The song came after thinking about how people often complain about the very things that could and should be seen as a gift. Like the simple act of getting caught in the rain.

“Humans are remarkably good at denying the truth sometimes and covering it up with a bunch of other crap that we pretend is more important. We tend to just wanna get on with our lives, and not think about the scary things inside us, or with this planet we live on. This song is my take of an easy-breezy ’60s song to keep cruising along to, until the moment it’s all too late.” – Jordie Lane

Track Credits: Written by Jordie Lane.

Produced by Jordie Lane & Jon Estes.

Video Credits: Director, director of photography, editor – Korby Lenker

Aerial photography – Travis Nicholson

Producers, production designers – Jordie Lane & Clare Reynolds

Unspoken Tradition, “Georgia In Her Eyes”

Artist: Unspoken Tradition

Hometown: Cherryville, North Carolina

Song: “Georgia In Her Eyes”

Release Date: May 3, 2024

Label: Mountain Home Music Company

In Their Words: “‘Georgia In Her Eyes’ is a deeply personal song that I wrote in a fit of inspiration not long after meeting the woman who is now my wife. Looking through the perspective gained from 12 years together, the lyrics are even more meaningful. I’m excited that the guys in the band chose to help bring this song to life.” – Sav Sankaran, bass and songwriter

Track Credits:

Audie McGinnis – Acoustic, vocals

Sav Sankaran – Vocals, bass

Tim Gardner – Fiddle, vocals

Zane McGinnis – Banjo

Ty Gilpin – Mandolin

Donovan Woods, “Back For the Funeral”

Artist: Donovan Woods

Hometown: Sarnia, Ontario, Canada

Song: “Back For The Funeral”

Album: Things Were Never Good If They’re Not Good Now

Release Date: July 12, 2024

Label: End Times Music

In Their Words: “‘Back For The Funeral’ is a story that a lot of us end up experiencing. Big life events – deaths, births, divorces – seem to pull us out of the flow of time somehow. The days around these events can feel like a dream wherein the regular rules of our lives don’t apply. People fall back onto old habits or maybe construct a new temporary-self to shield them from grief or shock. What I like best about this song is that it reflects that dream-like feeling without sacrificing clarity. It feels the way those life-dividing days feel. I wrote it with Lori McKenna and Matt Nathanson. I’m about as proud of it as anything I’ve written. I hope it’s useful to people.” – Donovan Woods

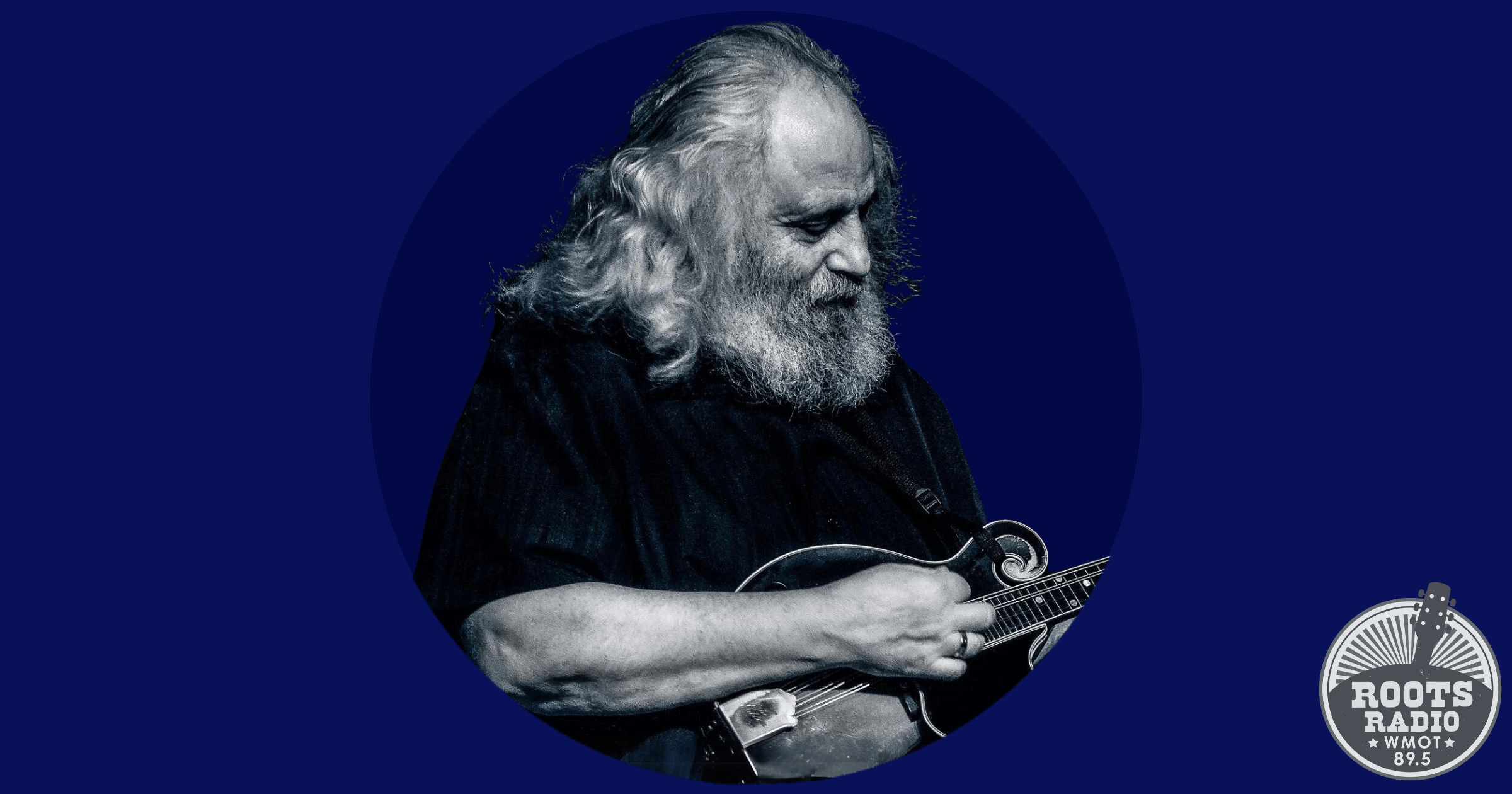

Meadow Mountain, “June Nights” (SkyTheory Sessions)

Artist: Meadow Mountain

Hometown: Denver, Colorado

Song: “June Nights”

Release Date: April 30, 2024 (single)

In Their Words: “It sometimes feels like my life is split up into eras – periods of a year or two that, upon looking back, have a distinct, overarching feeling. As I get older I’ve started to recognize when I’m on the edge of one era, moving into the next one, and I begin to get a sense of the overall color of my recent life. I had that feeling as spring moved into summer last year and wanted to document it in a song. It recounts moments in the Colorado wilderness, misadventures in love, and my abiding wish to be Sam Bush in the 1980’s.” – Jack Dunlevie, mandolin and songwriter

Photo Credit: Carson Peters by Cora Wagoner; Jessie Wilson by Sam Aldrich.