Writer Marty Godby called it “The convergence of 1975.”

The elements: a band that would only be together for 10 months, a benevolent venture capitalist who loved bluegrass, and an upstart record label from Boston. The resulting product was unprecedented and unforgettable: The New South, Rounder Records 0044. Bluegrass fans know it simply as “0044.”

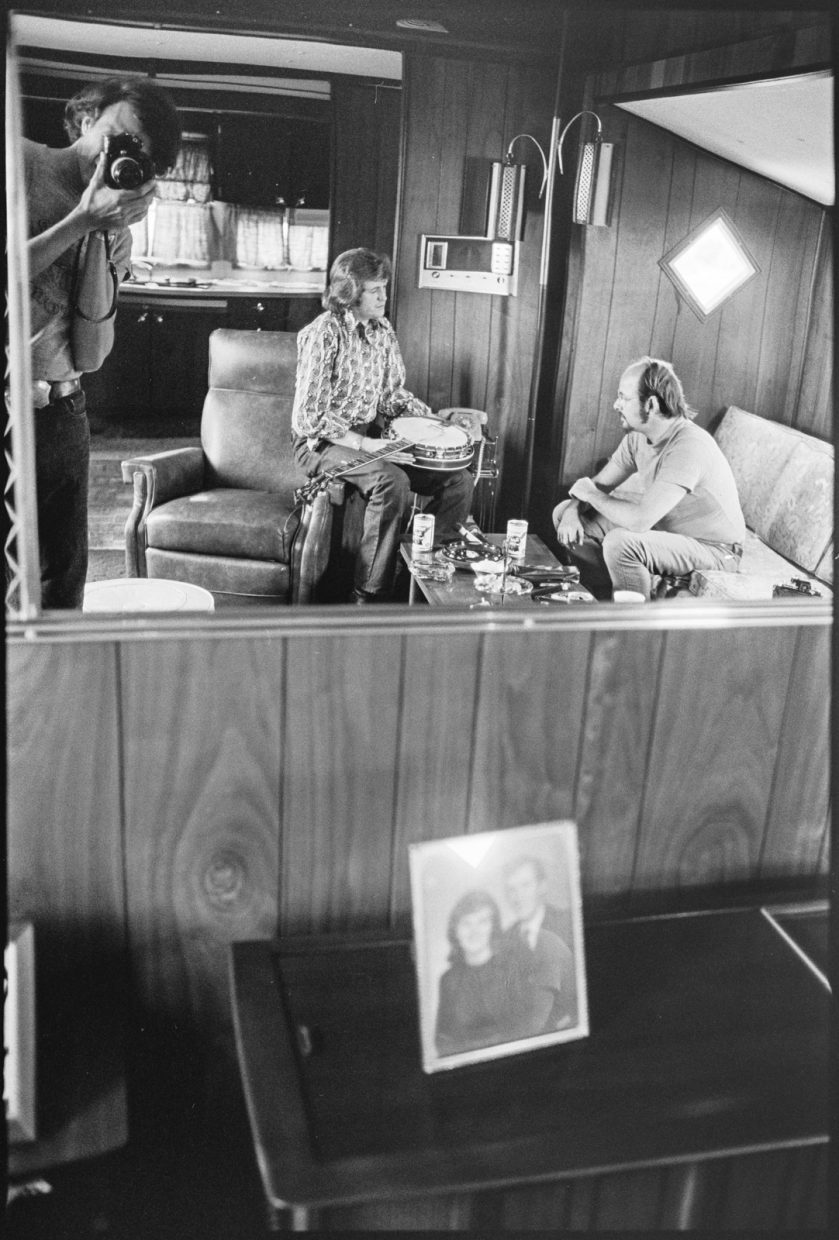

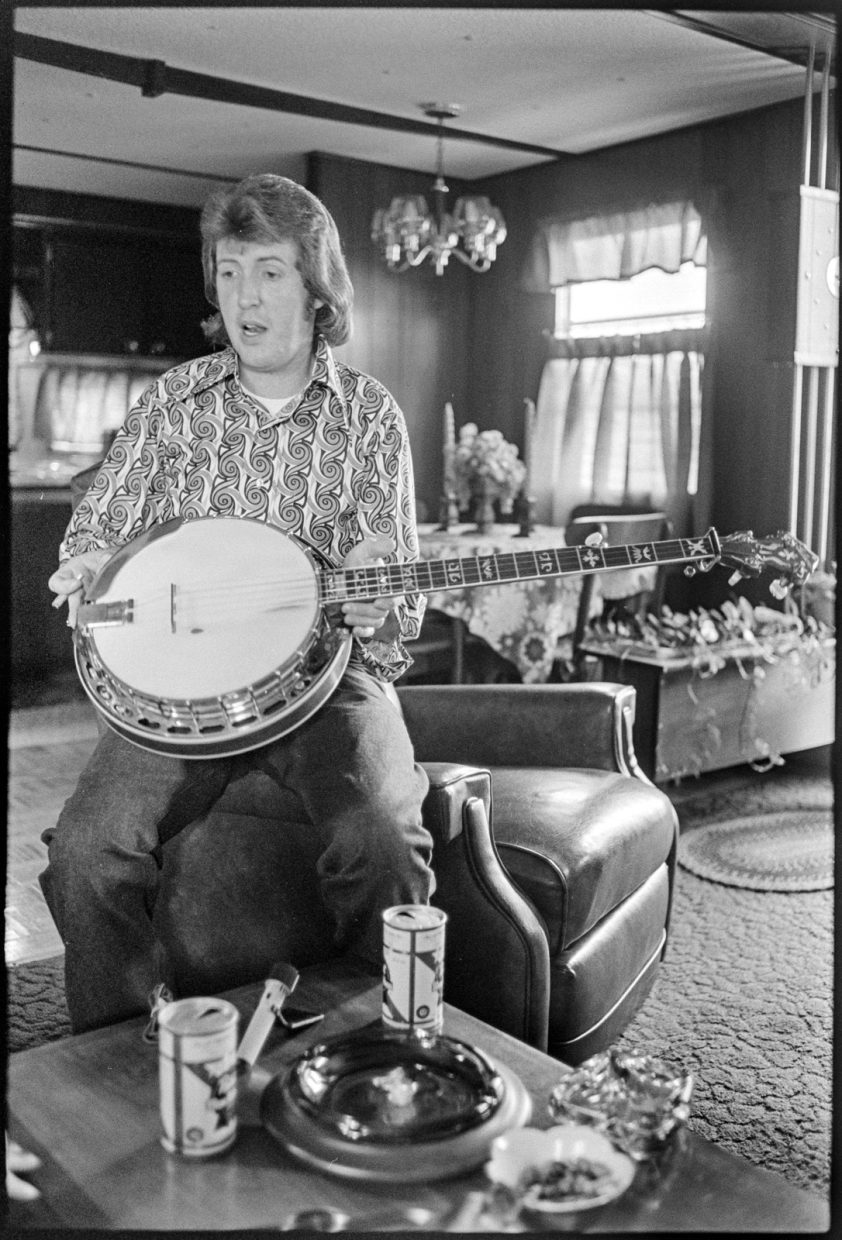

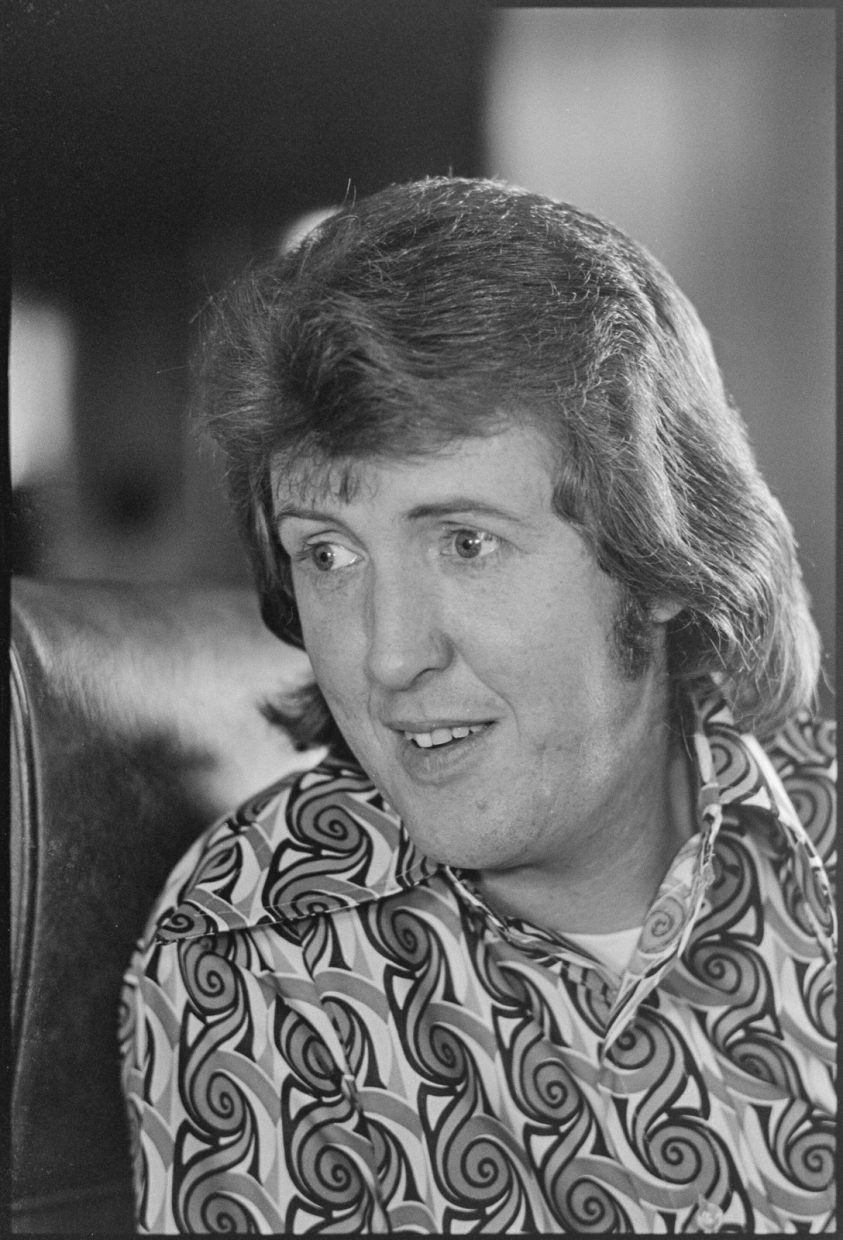

The New South of this recording was J.D. Crowe on banjo; Tony Rice on guitar; Ricky Skaggs on mandolin; Bobby Slone on bass; and Jerry Douglas on Dobro. The impact of that configuration and the album were stunning. Yet, within a year of the recording, Rice would leave to become a founding member of the David Grisman Quintet. Skaggs and Douglas formed Boone Creek. Crowe and Slone continued performing together for years.

Rounder 0044 was influential enough to be preserved in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry in 2024 and was awarded induction into the GRAMMY Hall of Fame this year. This month, Real Gone Music will re-release the album on vinyl, as will Craft Recordings later this year on compact disc.

Both the origin story and legacy of 0044 have inspired great narratives, probably more than any other bluegrass album. Bill Nowlin, one of the three founders of Rounder Records, wrote three articles for BGS on the album’s 40th anniversary. They offer a step-by-step look at what happened in 1974 and 75, plus hilarious and poignant anecdotes and quotes.

David Menconi dedicated a chapter of his excellent book, Oh, Didn’t They Ramble: Rounder Records and the Transformation of American Roots Music, to 0044. In 2016, radio host Daniel Mullins focused his college history capstone project on the album. Of course, it was 44 pages.

THE SHORT VERSION

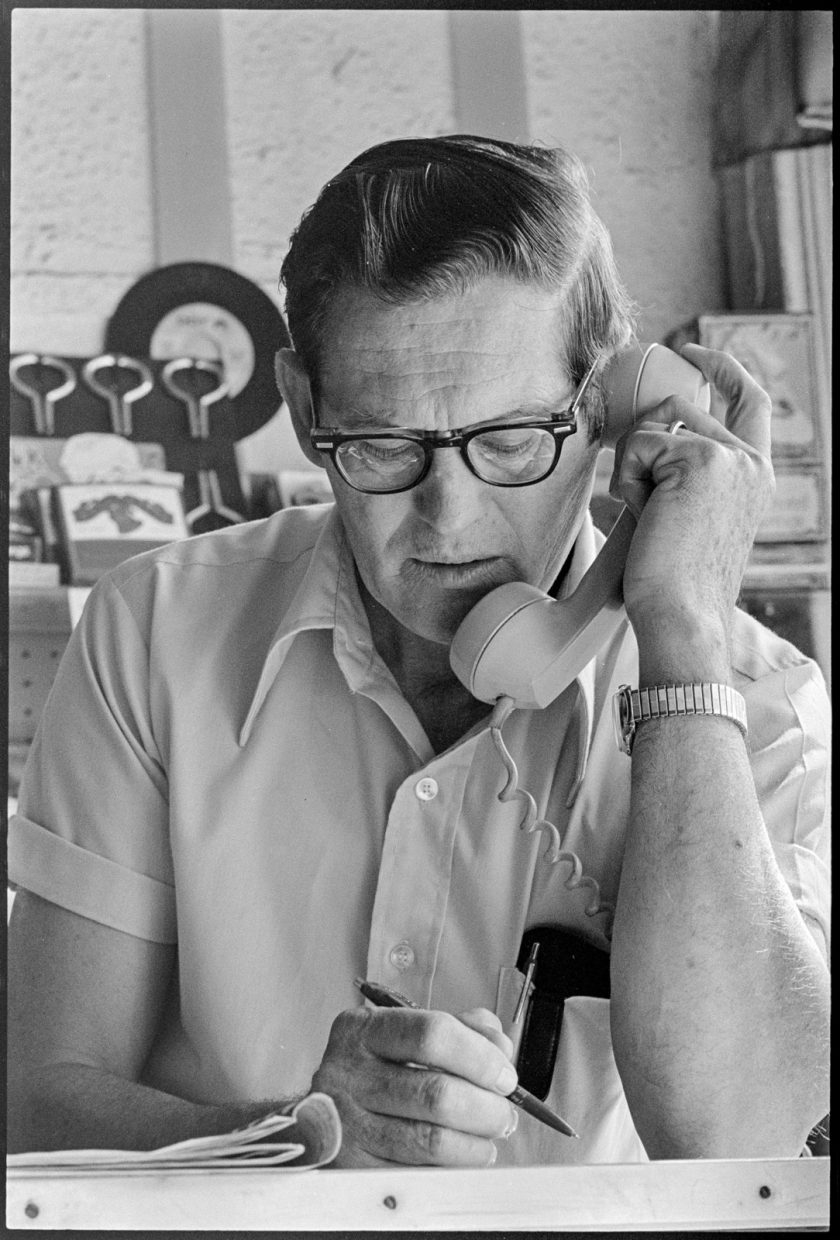

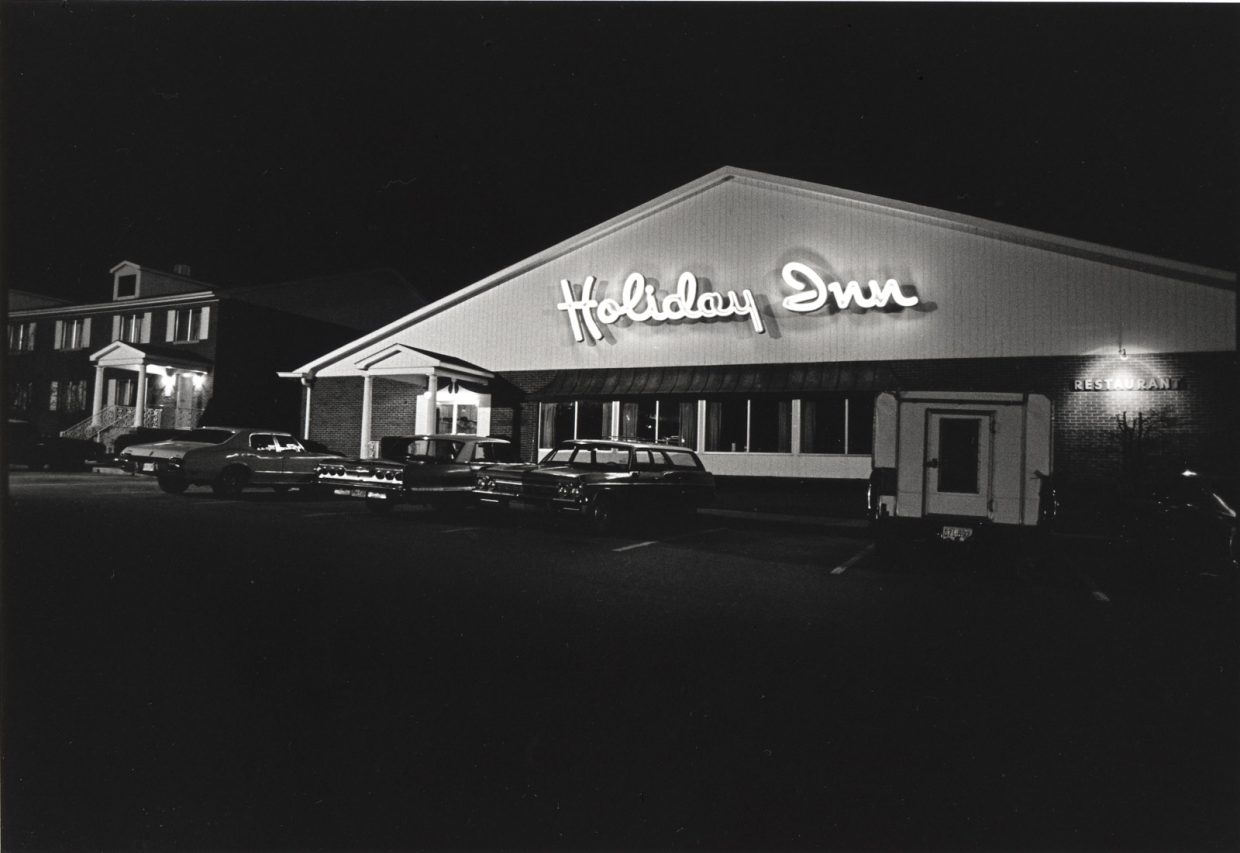

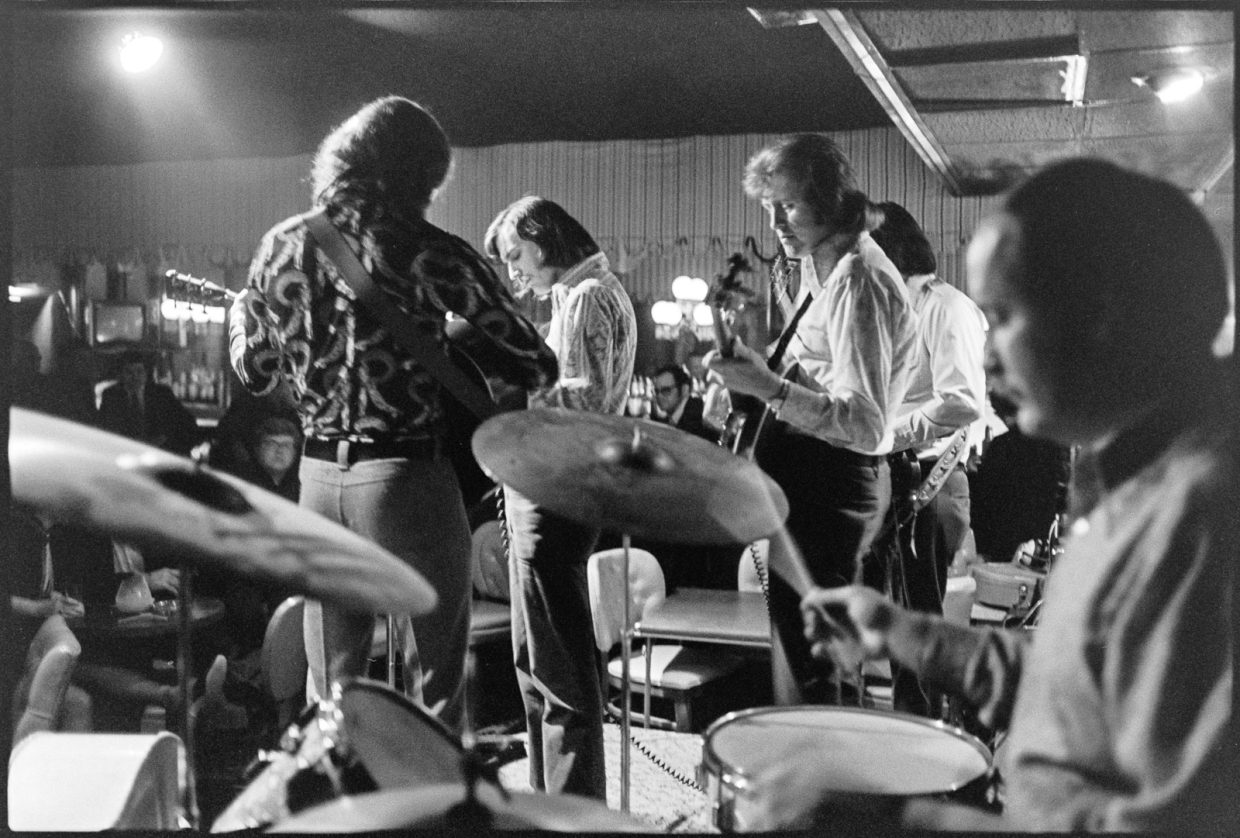

J.D. Crowe, already revered for his banjo playing and baritone singing, led a band called The Kentucky Mountain Boys. From 1968, they had a six-nights-a-week gig at the Red Slipper Lounge in a Lexington, Kentucky Holiday Inn. Crowe added non-traditional bluegrass instruments and songs to the Holiday Inn repertoire. This was as much to please a diverse audience as it was to keep the musicians from getting bored. In 1971, Crowe changed the band’s name to The New South.

Of the name change, Rounder’s Marian Leighton Levy said, “It was obvious that this was a new kind of bluegrass.” From a broader view, “It was an era when the South was, in a way, trying to self-consciously reinvent itself as a new, modern place. And they [The New South] were kind of the musical representation of that wider political context.”

It was the ’70s, and change was brewing – even in the tightly controlled world of country music, Levy noted. Around the same time, Willie Nelson and his Outlaw Country compatriots were reaching out to new songwriters and moving away, physically and musically, from “the factory system of Nashville publishing companies.”

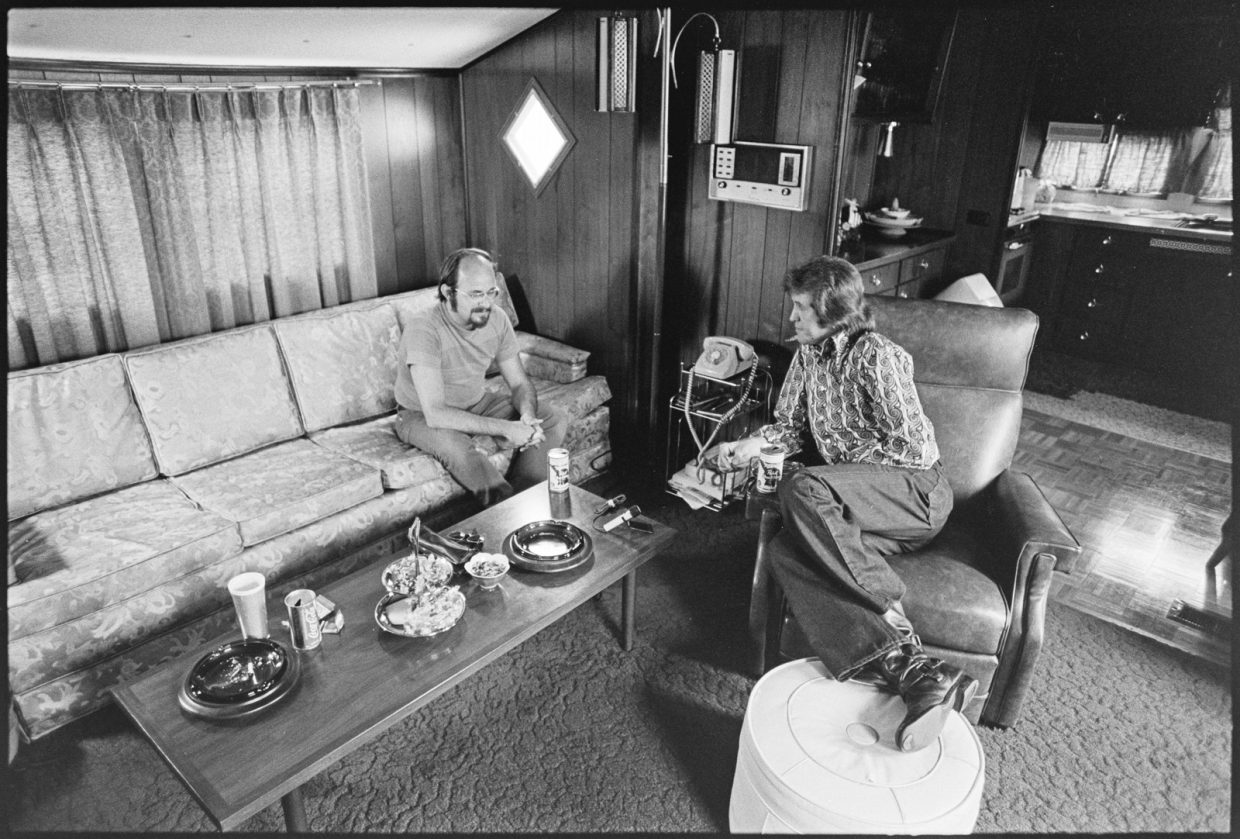

In 1974, lead singer Larry Rice left the New South and brother Tony took over singing lead. Ricky Skaggs’ pure tenor mixed with Rice’s unmistakable mid-range voice, creating a new, dynamic tension for their duets and trios. In the summer of that year, Crowe and the band toured without any product to sell. At the annual Gettysburg Blue Grass Festival, Crowe, his friend and manager, venture capitalist Hugh Sturgill, and the young founders of Rounder Records initiated “The Great Convergence” – an agreement for a studio recording. An innovative contract led to the first New South album.

THE BLUEGRASS WORLD EXPLODED

As soon as they heard the test pressing, the Rounder founders knew they had something remarkable on their hands. “Jack Tottle [who, along with John Hartford, wrote liner notes for the album] was stunned, and he kept saying, ‘This is one of the most amazing records ever made.’ And he was not given to exaggerating,” Levy said.

“It was clear. It was crisp … and the more you played it, the more you wanted to hear it.”

0044 came out in the spring of 1975. Levy said by festival season, other bands were playing the tunes from the record “pretty much note for note.” One observer said that at one festival, almost every band on stage played “Old Home Place.”

So, what is it about that record? Let’s start with the musicians. Skip Heller, who initiated the 0044 Real Gone Music reissue, said everyone in that group of players “would talk about it like it was high school prom and their first love … they had all been in good bands before, but this was the first time they had been in a band that was as great as anything in bluegrass music had ever been.”

Levy said, “They absolutely knocked each other out. … And I think that long before anybody heard the record, they knew the band would stand the test of time – because of all of them, not just one person.”

The record’s title was The New South. Only after the first printing sold out, three band members had moved on, and it was time to redo the cover (read about the cover photo – a great story in itself), was it retitled J.D. Crowe & the New South. Crowe, born in 1937, was the venerated elder and a banjo icon. After entering Jimmy Martin’s boot-camp-of-a-band at age 18, he developed impeccable timing, his own take on Scruggs-style banjo, and excellence as a baritone singer. And he knew how to pick his band members.

The influences of Tony Rice (age 24 at the time) on bluegrass and related music are limitless – from cementing the role of guitar as a lead bluegrass instrument, to modeling impeccable rhythm playing and singing, to excelling in so many genres outside the bluegrass boundaries. At 21, Skaggs had the instrumental chops, a stunning voice and the instincts to become successful in both country and bluegrass. Rounder’s Ken Irwin attributes much of 0044’s innovation to Skaggs, including bringing a teenaged Douglas into the mix.

Douglas is to Dobro what Rice is to lead guitar. Fifty years later, after 14 GRAMMY awards and countless other honors, he continues to inspire and encourage musicality and creativity in Dobro playing. Touring with Alison Krauss since 1998, it’s likely that he has been heard live by more people than any other resophonic guitar player. Of the veteran, Bobby Slone, Mullins said, “Everyone in the band wanted to make sure that Bobby got a lot of credit. … He was such a rock solid force on that band, not just on bass, but as far as camaraderie was concerned.”

By the time The New South entered the studio, Crowe, Slone, and Rice, later joined by Skaggs, had spent hundreds of hours performing together at the Holiday Inn. Individually, they were superb musicians. Together, they were as tight as a band could be.

THE SONGS

Long before 0044, Crowe had blasted out from under bluegrass constraints, incorporating songs like Fats Domino’s “I’m Walkin,” and at Larry Rice’s suggestion, The Flying Burrito Brothers’ “Sin City.” The songs on 0044 were just a small set of a huge repertoire. While the unconventional musical choices sparked controversy among traditionalists, they also sparked a flame of excitement that spread quickly and widely.

In 1975, Mullins said, Ralph Stanley & the Clinch Mountain Boys, Jimmy Martin, and Bill Monroe were still “killing it” at festivals with their first generation bluegrass sound. “On the other end of the spectrum, Seldom Scene recorded Live at the Cellar Door,” an immensely popular recording, that year. Like the Country Gentlemen, the Scene had been recording songs totally out of the bluegrass box, using bluegrass instrumentation, but with an emphasis on rich melodies and harmonies, rather than just the drive of traditional bluegrass.

Mullins said, “You go to Crowe, who’s got the street cred from all his records with Martin, but he’s also looking ahead, and so he’s able to get it all in there. A lot of bands were playing to one side or the other … but to have one that hit right in the middle, right at that time, was unreal.”

“When they saw J.D. Crowe’s name up front, and they knew that he had played banjo with Jimmy Martin on all those records they had loved for 20 years, it probably made some of those hard-edged fans pay more attention,” he said.

Whatever the dynamics of the time, The New South became synonymous with great bluegrass. And 0044 made Ian Tyson’s songs forever acceptable in bluegrass jams.

ON AND ON

Kristin Scott Benson, six-time IBMA Banjo Player of the Year, was born the year after 0044 came out. Benson said she was about nine the first time she saw J.D. Crowe. He was playing with the Bluegrass Album Band, “and that was a formative experience. That band was so explosive, and the crowd had an air of chaos, because everybody was so excited to hear the band. Every time Tony Rice ended a solo, you couldn’t hear any music.” (Because of the crowd noise.)

It would be four years until she picked up the banjo, and two more years until she learned about The New South album – and what it meant to a banjo player.

On 0044, she says, “If you just talk quintessential banjo solos, you’ve got ‘I’m Walkin’ and ‘You Are What I Am.’ His tone is aggressive. It’s just such confident, groovy, greasy, pristine banjo. It’s impossible to overstate how good it is and how influential it is.”

“But I think you should listen to his contributions on the less banjo-friendly songs [‘Home Sweet Home Revisited,’ ’10 Degrees’], because Crowe was great at that. He was a magical backup player.”

Billy Failing, who currently plays banjo with Billy Strings, agrees. Failing started out his banjo life drawn to more progressive players like Béla Fleck. But, he said, “As time goes on, the more I circle back to J.D. Crowe. I think of how much of a gold standard he is for bluegrass banjo, and how interesting his playing is.”

“He’s considered a traditional player,” Failing continued, “but then I’m always hearing some lick that surprises me. It’s been a gradual thing, but it becomes more meaningful as time goes on. I was just listening to The New South album, and on ‘Cryin’ Holy’ – it’s just so slamming! He’s turned it up to 11 constantly on that one.” And, like Benson, he points out what he calls Crowe’s “intricate touch” on banjo.

“It’s such a cool kind of push and pull between whether he’s out front or whether he’s playing backup … it catches your attention in such a cool way.”

Benson said, “It’s easy just to be drawn to those obvious picks [like ‘Old Home Place’] but the album is so much deeper than that. This particular band presented a tightness and a level of execution that was new – I don’t think there had been a bluegrass record up until that point that was so well done.”

“The vocals, the arrangements are so well thought out. Everybody’s playing so well together. It was just a special moment and a special group of people, and I think it raised the bar for bluegrass albums,” she said, and made an imprint on so many contemporary musicians.

Benson poses the question, “Who’s the most influential modern bluegrass guy? It would have to be Tony Rice, because he affected the genre with his rhythm guitar playing, which is phenomenal. And that type of rhythm playing affects the entire groove of the band. It became the new standard, what most people go for.”

“Never discount the importance of his rhythm,” she continued, “and then obviously his lead playing, but also his singing and his material choice … so if someone pinned me down and I could only name one, he might be the guy.”

Failing, speaking of his bandmates, said, “Everybody’s inspired by The New South. I hear Billy [Strings] constantly talking about his inspiration by Tony Rice, and Jarrod [Walker] by Ricky Skaggs.” (Walker wrote liner notes for the Real Gone Music re-release.)

Mullins noted that the Rice/Skaggs blend – a lead singer with a baritone-range voice coupled with a high tenor – established a hair-tingling blend that continues to be emulated, from Ronnie Bowman and Don Rigsby in Lonesome River Band through Alison Krauss’ duets with Dan Tyminski and Russell Moore.

Benson said, “It’s an important record for the genre as a whole, and it’s also an important record to me, personally, and really, to any banjo player who is serious about learning. It’s one of those essential albums.”

UNANSWERED QUESTIONS

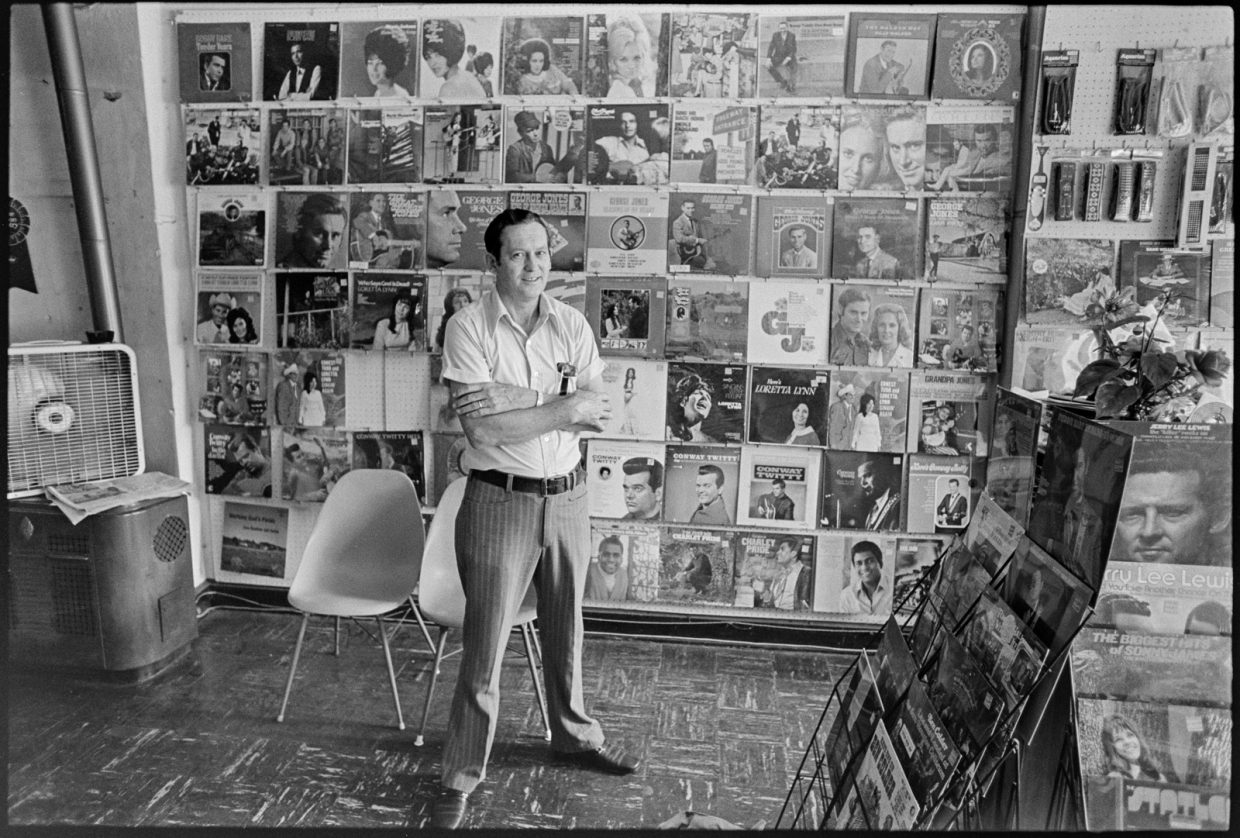

First, how did it come to be widely known as 0044? Well, nobody’s sure. Irwin and Levy remember being in the very early stages of their operations at the time – with both a new label and a new distribution company. All three Rounders had been totally immersed in music, but they were learning the business as they went, developing it on their own terms.

Levy speculated, “It is possible that it went back to when we were just calling records by their numbers,” when there just weren’t that many products. “So, it may have been something we started when we were talking, and other people picked up on it, not intentionally. And we thought it was sort of humorous.”

And how did members of Emmylou Harris’ Angel Band get left off the credits, as well as the fact that J.D. played guitar on it? John Lawless goes into depth in his fascinating Bluegrass Today article.

HAPPY 50TH BIRTHDAY

As the liner notes to the Real Gone Music re-release say, “Virtually no other album anywhere in history is known to its audience by its label number. Not Kind of Blue, nor Pet Sounds, Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations, none.”

That says quite a bit about the recording’s importance. So does the fact that two labels are issuing re-releases this year.

The Real Gone Music edition is pressed on gold-colored vinyl for its golden anniversary. Both re-releases contain two cuts not included on the original product: “Why Don’t You Tell Me So?” and a version of “Cryin Holy” with Emmylou’s voice in the mix.

Failing sums up what 0044, J.D. Crowe, and the musicians he surrounded himself with mean to him and to many of the pickers making the best music today.

“Every time I circle back to the Bluegrass Album Band, The New South, and J.D. Crowe, I’m reminded, ‘that’s how it’s done!’”

Photo Credit: Phil Zimmerman

Wear your love for 0044! Shop our exclusive RR 0044 tee on the BGS Mercantile here.