Artist: The Brother Brothers (Adam and David Moss)

Hometown: Peoria, Illinois

Latest Album: Calla Lily (out April 16, 2021, on Compass Records)

Which artist has influenced you the most … and how?

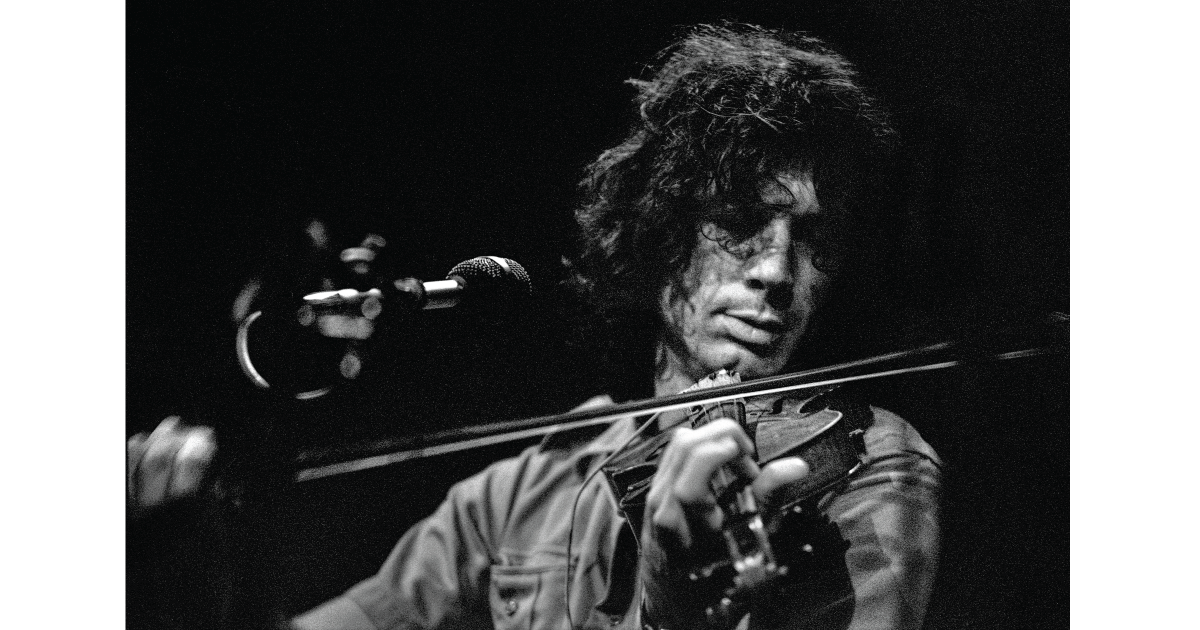

If I have to pick one, which is quite difficult, I’d have to pick John Hartford. I constantly admire, rediscover, and celebrate the effortlessness with which music and words flow out of him. When he writes, he writes about what he knows, and we are convinced to join him in his love of steamboats, old time Nashville, and so many other things that I’d normally walk on by. His musicality is so honest and of himself, and damn, it just sounds so good. He doesn’t subscribe to any “rules” and yet he’s so completely inside a style. — Adam

What other art forms — literature, film, dance, painting, etc. — inform your music?

I have done a fair share of composition for dance, which has opened a whole new universe of creativity to me — the idea that movement, once catalogued, becomes an intentional means of expression has such a real and vibrant quality that no other art form can ever hope to encapsulate. Working with ballet dancers is amazing because the rigid tradition and pure athleticism of the art form creates an amazing palette that can really get inside different kinds of music, and the creativity flowing from choreographers of modern dance in NYC and around the world is just something so otherworldly but yet incredibly accessible. For some reference, I would recommend Batsheva Dance Company and the surrounding tradition of Gaga, and Nederlands Dance Theater. And of course the ever famous and incredible stewards of George Balanchine, the New York City Ballet. — David

Which elements of nature do you spend the most time with and how do those impact your work?

This last year we’ve both been displaced by the pandemic and as a result have continuously traveled. Now, David is living with his fiancée and their dog in a scamp trailer, spending every day entirely surrounded by nature. I’m currently living in California and surfing every day. When you make your life in nature, you can’t help but let the waves and your wetsuit influence your rhythm and rhyme. The sunset is an impossible thing to describe, but we can keep trying. — Adam

What’s the toughest time you ever had writing a song?

There isn’t really such a thing as “a tough time writing a song,” in my experience. Songs, for me, are things found and worked out. If the process feels difficult, it usually requires waiting and trying different avenues. If you asked, “What is the longest it’s taken to write a song?” The answer would be a very very long time. — David

Since food and music go so well together, what is your dream pairing of a meal and a musician?

Honestly, I can’t imagine a better pairing than Russ & Daughters’ smoked fish spread and dancing to one of the hottest klezmer bands in NYC. Second only to that would be another trip to Lafayette, Louisiana, to spend another weekend at Blackpot Festival, hanging with our Cajun friends down there, playing music and eating the contest-winning gumbo, jambalaya, and gravies of the year. — Adam

Photo credit: Shervin Lainez