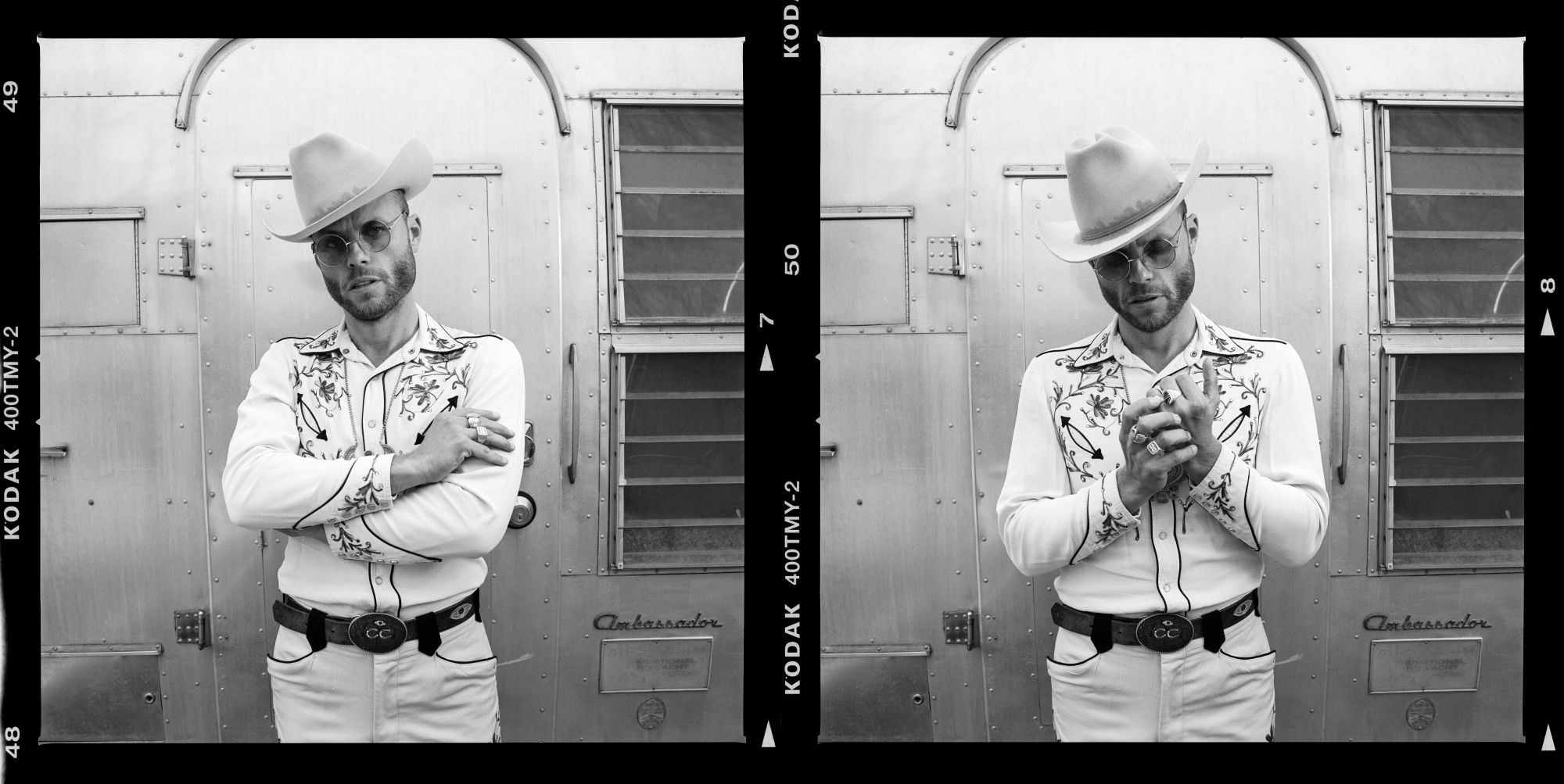

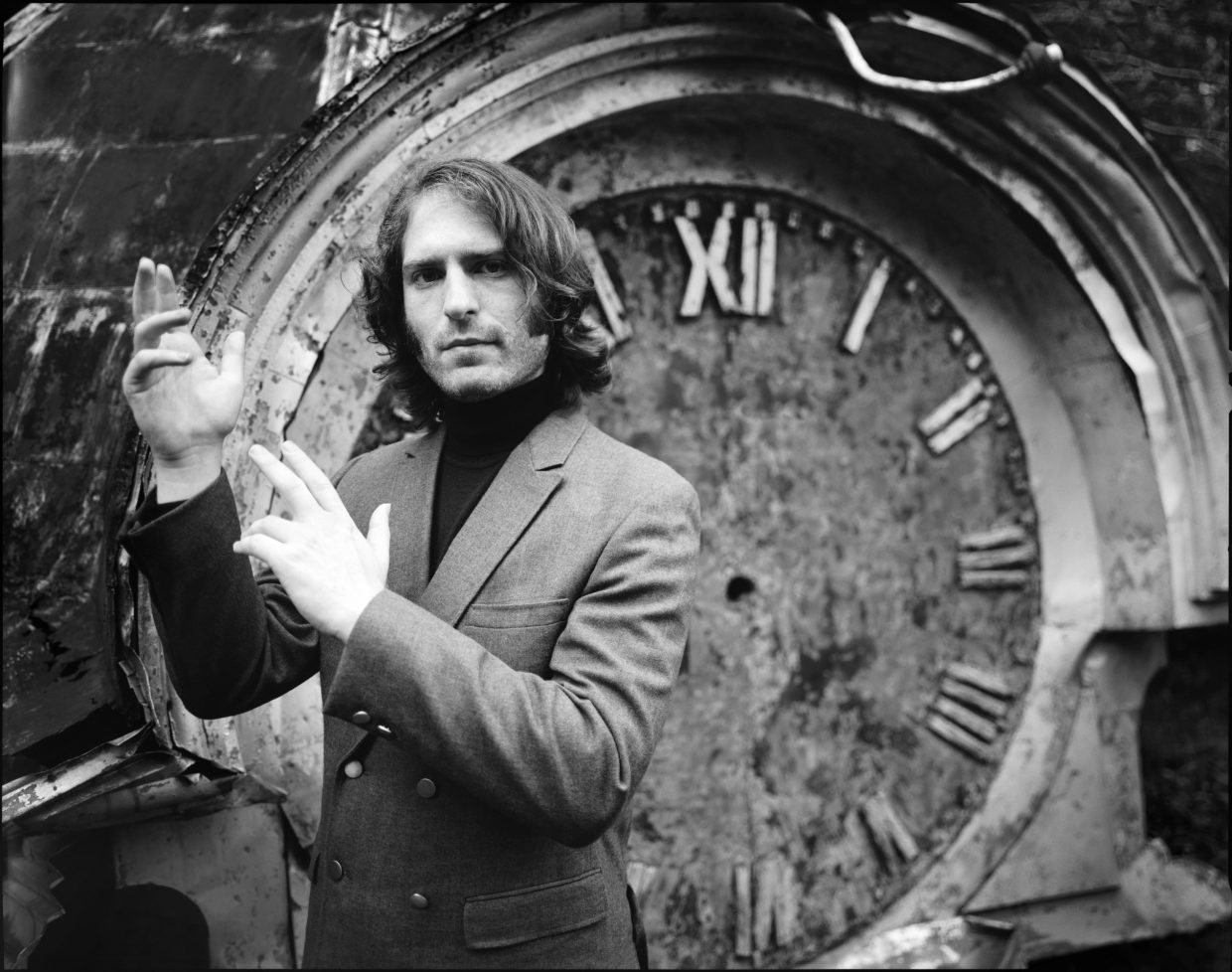

From my early days of being photo editor of my high school newspaper to my current tour hobby of photographing bizarre regional potato chip flavors in their native lands for @chipscapes, I have long held a fascination for photography. As life rushes by us at a mile a minute a camera has the ability to freeze the frame for a second, capture a moment in time, and provide photographic evidence that the moment actually existed. Though the waves may have crashed into your impossibly magnificent sand castle, you can keep it standing forever in a photo. And though time may have drowned out a love that once burned impossibly bright, a security camera may have accidentally captured the most blissful moments of that love and if you can track down the footage and find those moments, you could potentially kick back on the couch and watch those moments on infinite loop forever.

This is the premise of my song, “Security Camera,” from my new album Comeback Kid. Beyond that song, the subject of photos, memories, and trying to hold on to a moment for what it was, to love that moment forever in spite of its ephemeral nature, weaves its way through the album as a common thread. I put together a playlist of songs on the theme of cameras and memory and it turns out a lot of my favorite songwriters and biggest influences have also been fascinated by this subject. Recorded music is basically the audio version of a photo/video, so it makes sense. Hope you enjoy these songs as much as I do. – Bridget Kearney

“Kamera” – Wilco

Jeff Tweedy seems to be using the camera as a self-revealing truth teller in this song. He’s lost his grip on reality and only a camera can tell him “which lies that I been hiding.” I have loved Wilco for a long time and have a very specific visual memory of listening to them on headphones in college: I was on a semester abroad in Morocco and I was going for a run along the beach in Essaouira and came upon these big sand dunes. I spontaneously decided to run up to the top of the dunes and then bound down them into the water. This joyous discovery of dune jumping on a perfect sunny day will always be soundtracked to Wilco’s song “Theologians” in my mind.

“Kodachrome” – Paul Simon

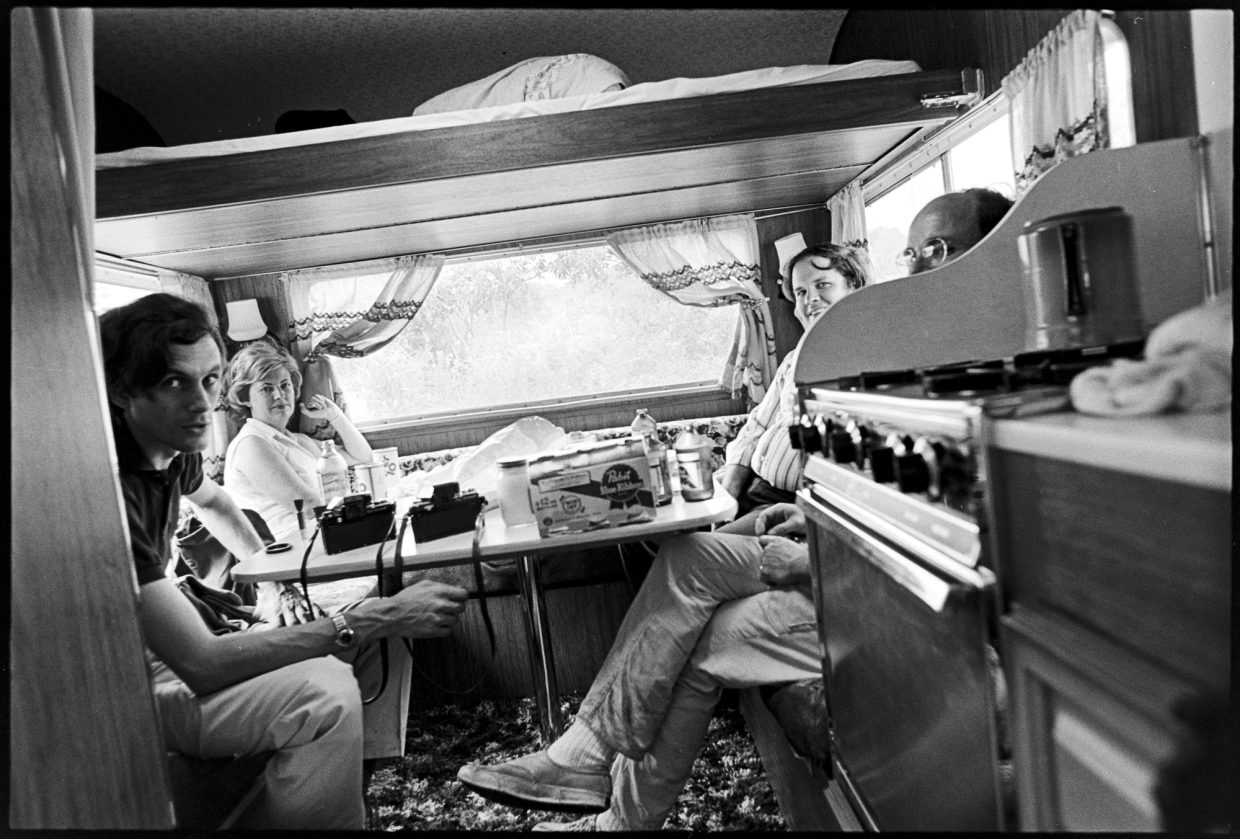

Paul Simon was always playing around the house when I was growing up and this song has a particular significance to the origin story of my band, Lake Street Dive: We were on one of our first tours and we were driving my parent’s minivan around the Midwest. The only way to listen to music in the van was through the CD player. It was in the pre-streaming era where we all would have had a big library of digital music on our laptops (probably illegally downloaded from Napster or the like). So we decided to co-create a mystery mix CD by passing around someone’s laptop and letting each of us put in songs one-by-one, not telling each other what we’d put it in. Then we burned out the mystery mix CD and listened to it together.

As four students studying jazz at a conservatory we had mostly listened to Charles Mingus and The Bad Plus together thus far, but the mystery mix exposed all four of us pop music fiends. Song after song kept coming on and we’d go, “Oh my god, you like Lauryn Hill too?!” and “You also know every lyric to David Bowie’s ‘Life on Mars’?!” This culminated in the moment when the mystery mix played Paul Simon’s “Kodachrome” THREE TIMES IN A ROW! That was when we knew we should be a band forever. The groove on this song is also part of the inspiration for the song “If You’re Driving” from Comeback Kid.

“Hey Ya” – Outkast

Not actually a song about photos and you’re not actually supposed to shake Polaroid pictures, but Andre 3000 is one of the greatest musicians of our time and I’ve learned so much from him about music and language and spirit! Also this song is a total jam.

“Security Camera” – Bridget Kearney

I live in Brooklyn and there are security cameras everywhere here – at the bodegas, at the clubs, on the rooftops. Their purpose is to capture criminals in the act of committing a crime, but they are also capturing so many other things. Everyday things and extraordinary things. Moments of extreme beauty and moments of extreme pain. The idea behind this song is to track down security camera footage of the very best moments of your life so you can watch them on repeat.

“Pictures Of Me” – Elliott Smith

I went through a huge Elliott Smith phase in college and had an instrumental Elliott Smith cover band. His harmonies and melodies are so good that you don’t even need the lyrics, but adding them in, of course, makes it all the better. This one seems to say that pictures can lie to you, too.

“Picture In a Frame” – Tom Waits

This is one of those songs that seems like it has existed forever. “Ever since I put your picture in a frame” sounds to me like he is saying, “Ever since I decided to love you.”

“Body” – Julia Jacklin

My friend Michael Leviton (a great photographer and musician!) told me about this song and its passing but gutting reference to a photo. We were talking about how I had realized that a lot of my songs are about cameras and photography and how funny it is to look back at your own songs and see patterns and discover what you’ve been obsessed with the whole time. Michael said his thing is “curtains,” which appear over and over again in his songs.

“Bad Self Portraits” – Lake Street Dive

A song I wrote for Lake Street Dive years ago about what happens when the person you want to take a picture of steps out of the frame. What you’re left with and how to make the most of it.

“Videotape” – Radiohead

I always thought this song was about when you die and you are at the pearly gates of heaven, they are deciding whether you get in or not and watch back videotapes of your life to see if you were good or bad. I don’t know if that’s what Radiohead meant, but that’s my interpretation! The production is so cool, the way the drum loop is slightly off tempo and moves around the phrase slowly as it cycles around. Damn, Radiohead is so cool!!

There are a few songs on Comeback Kid that are directly Radiohead influenced. “Sleep In” is like Radiohead meets Ravel (or that’s what I was going for!) When I graduated from Iowa City West High School, I arranged a version of “Paranoid Android” that some friends and I played instrumentally at the graduation ceremony. In retrospect, that is a really weird song for us to have played at graduation! But I think it’s cool that they let us be brooding teenagers and go for it.

“When the Lights Go Out” – Sarah Jarosz

The song that gave Sarah’s brilliant new record its title, Polaroid Lovers. I feel so inspired by the music that my friends make, and Sarah’s songs from this album really knocked me off my feet when I heard the album and even more so when I heard them live!

“People Take Pictures of Each Other” – The Kinks

A festive little song about taking photos of things to prove that they existed.

“I Bet Ur” – Bridget Kearney

This is a song from the album I put out last year, Snakes of Paradise. The narrative is built around seeing a picture of something that you don’t want to see, letting your imagination fill in the details, and learning to accept it as truth.

“I Turn My Camera On” – Spoon

Groove goals. The camera here puts a bit of distance between you and the world.

“Photograph” – Ringo Starr

A song about photographs by my favorite Beatle? Yes, please!

“My Funny Valentine” – Chet Baker

I love Chet Baker’s singing, his pure, dry, affectless delivery, his deadpan panache. And I love the way this song manages to rhyme “laughable” and “un-photographable” and stick the landing.

“Camera Roll” – Kacey Musgraves

Photography has been around for a long time now but carrying thousands of photos of our lives organized in chronological order in our pockets at all times is relatively new. And both wonderful and terrible.

“Come Down” – Anderson .Paak

Just a passing reference to pictures in this song, but I had to get Anderson .Paak on the playlist because he’s the best!

“Obsessed” – Bridget Kearney

A song about falling quickly, unexpectedly, insanely in love with someone and trying to understand how it happened. You look back at the pictures as evidence trying to gather clues, see the train of events that led to this madness.

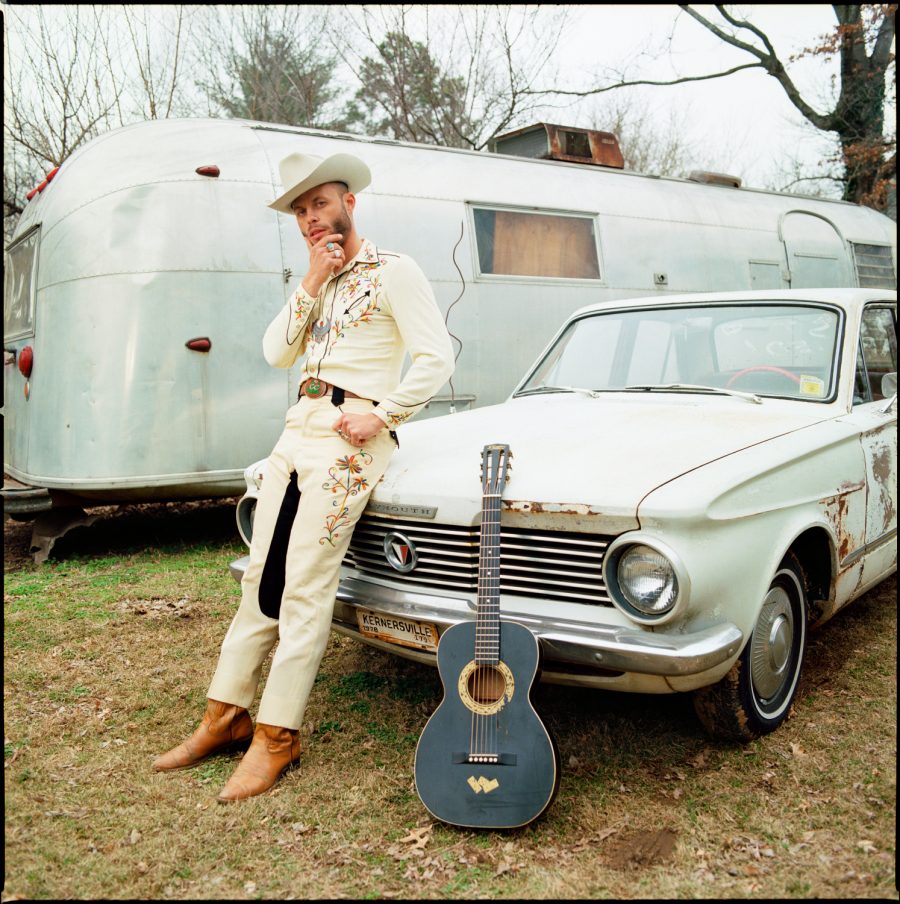

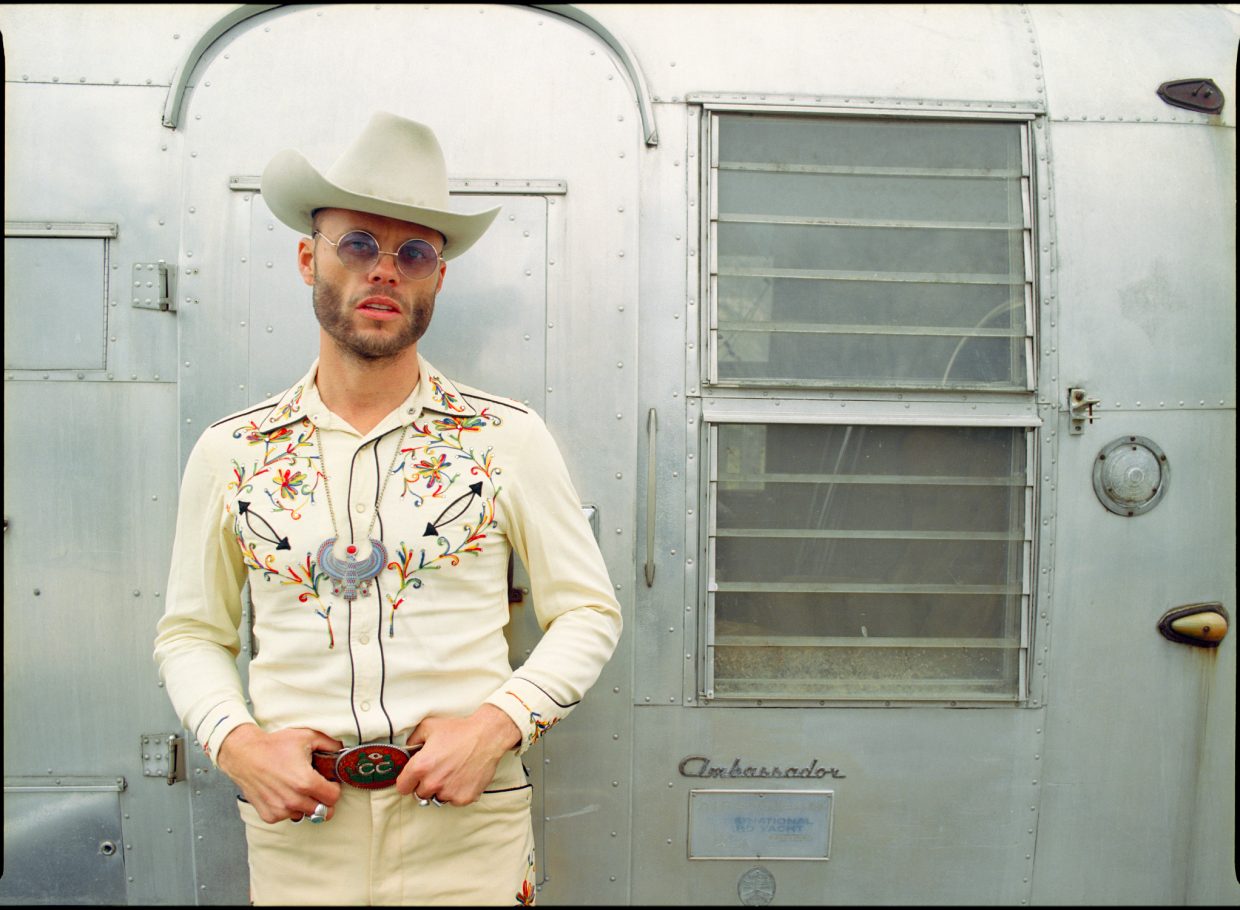

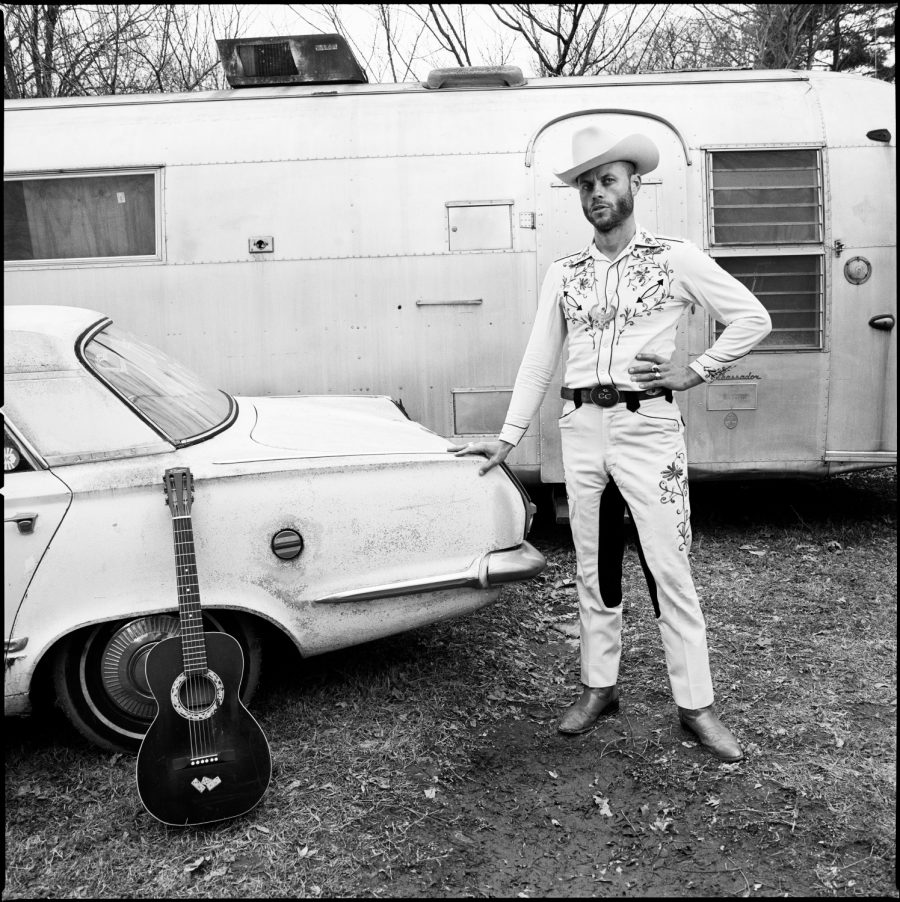

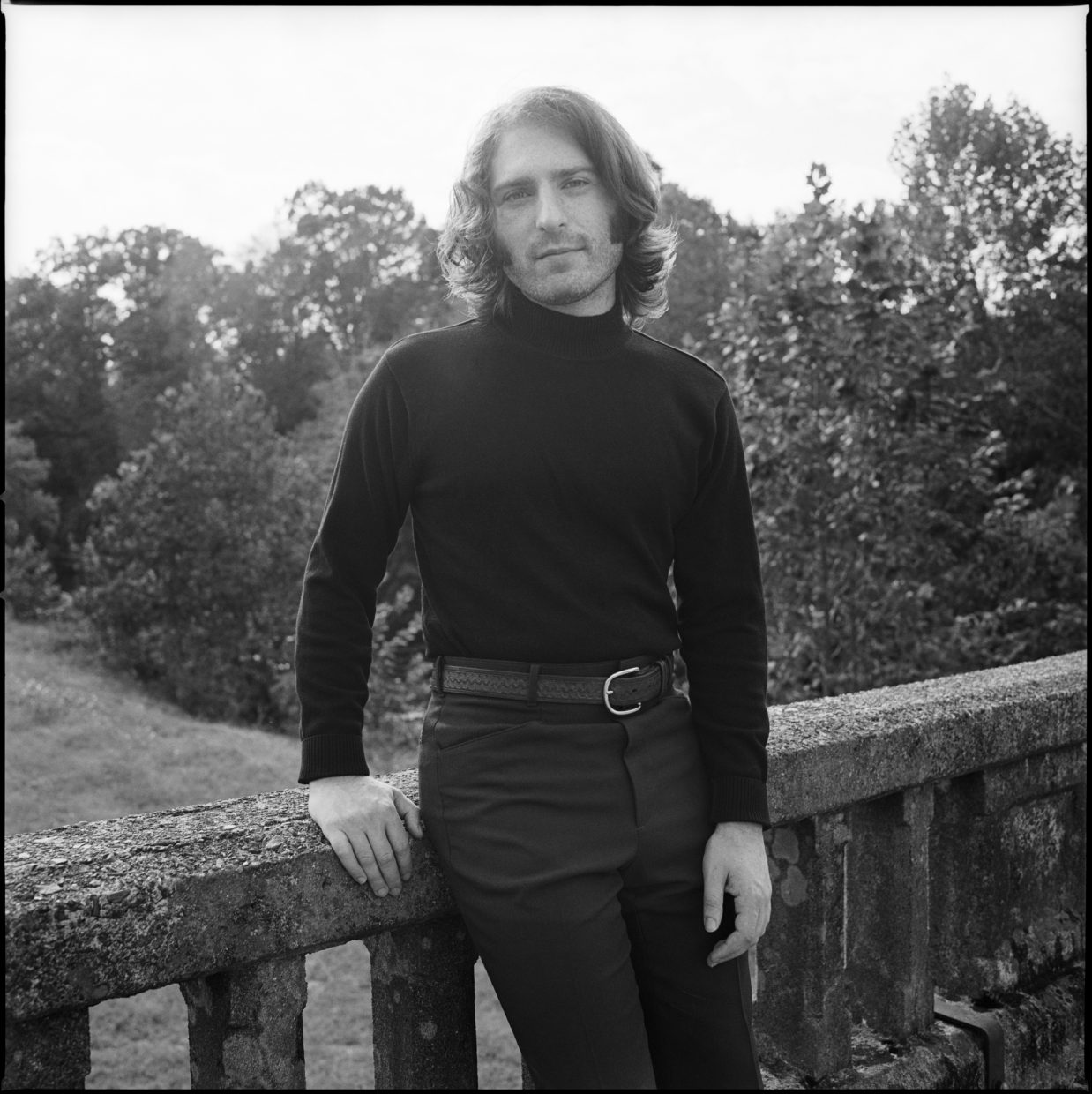

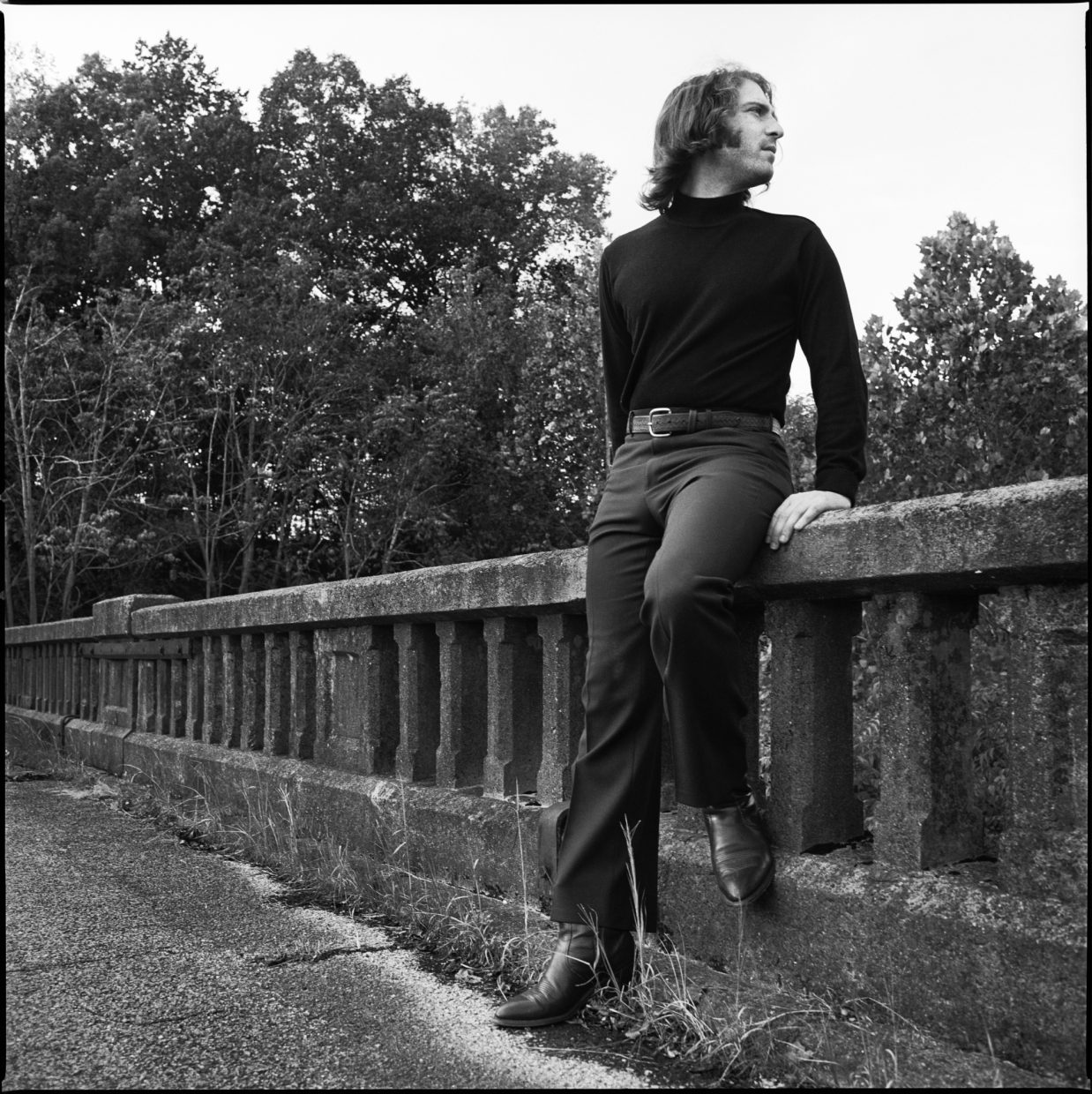

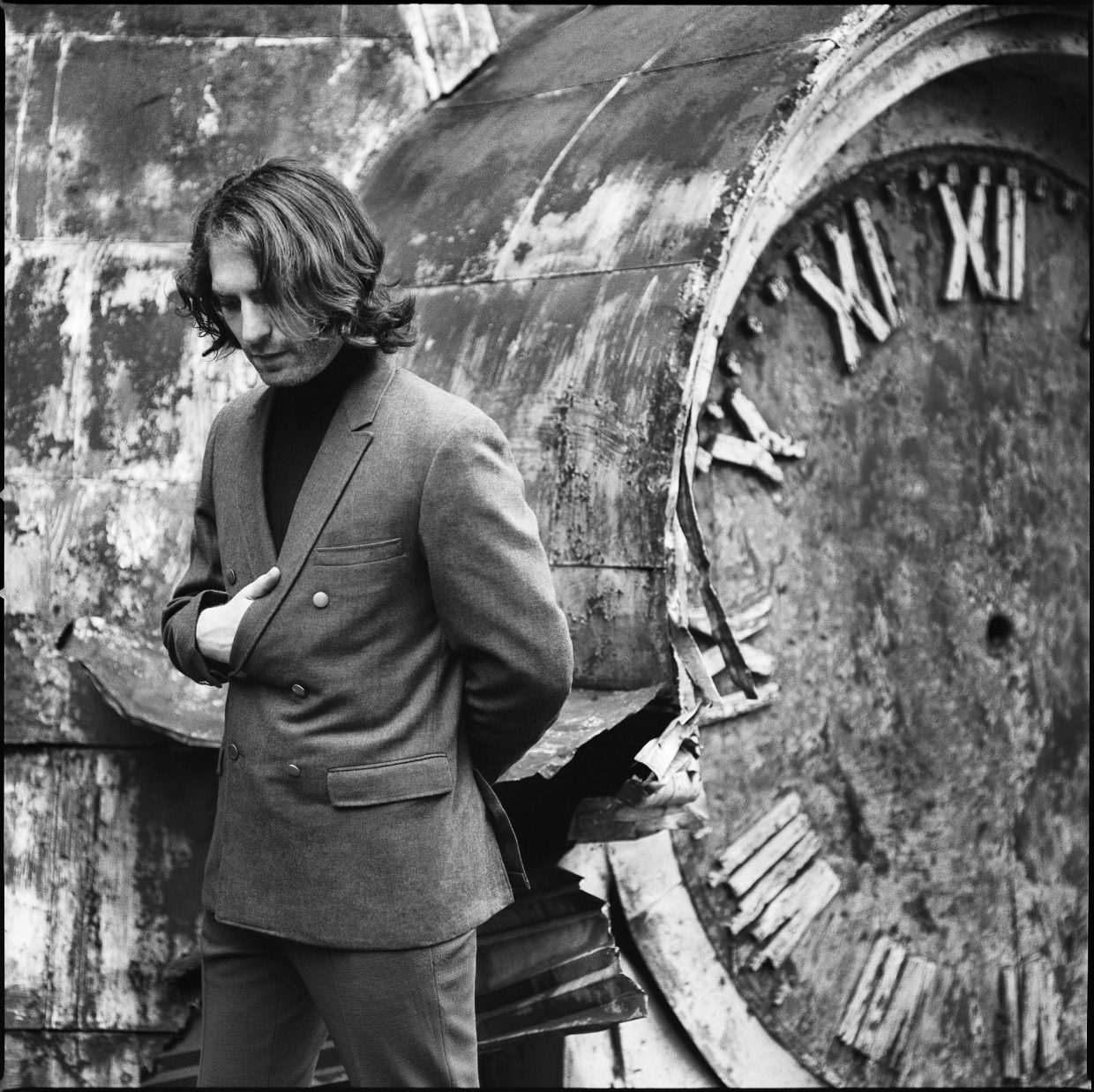

Photo Credit: Rodneri