The first time I heard Billy Strings’ name was in 2014, from a guitar picking pilot friend of mine from northern Kentucky who was working up in Michigan. I first met him at the Frankfort Bluegrass Festival in Illinois two or three years later, by which time I’d played a song or two from the Fiddle Tune X album on the satellite radio show I was hosting with Del McCoury. Billy had either recently gotten or was about to get his first IBMA Award for Momentum Instrumentalist of the Year (his then-roommate, Molly Tuttle, got one at the same time).

After that, I’d see him from time to time – I was already writing songs with fellow Michigander and Billy’s across-the-street neighbor Lindsay Lou – but it wasn’t until June 18, 2018, that we got together to write our first song, “Love Like Me.” We wrote a few more after that, he went into the studio, and put most of them on 2019’s Home. Since then, working as a team with another Michigander, Aaron Allen, we’ve written many more, for Renewal and now for Highway Prayers, too. To be honest, it’s been a little life-changing – a taste, at least, of what it must have been like for Music Row songwriters back in the day.

One striking feature of Billy’s trajectory has been his ability to keep the enthusiasm of the normative bluegrass industry and community that the IBMA generally represents; my social media feeds regularly remind me that most of the stalwart traditionalists among my friends – people who grew up immersed in scenes that trace back to the music’s earliest days – aren’t dissing Billy Strings. They’re cheering him on. That hasn’t always been the case with bluegrass artists bringing the sound and the songs to larger-than-usual audiences, but it’s indisputable here, as three successive IBMA Entertainer of the Year awards (finally supplanted this year by Del, another traditionalist admirer) demonstrate.

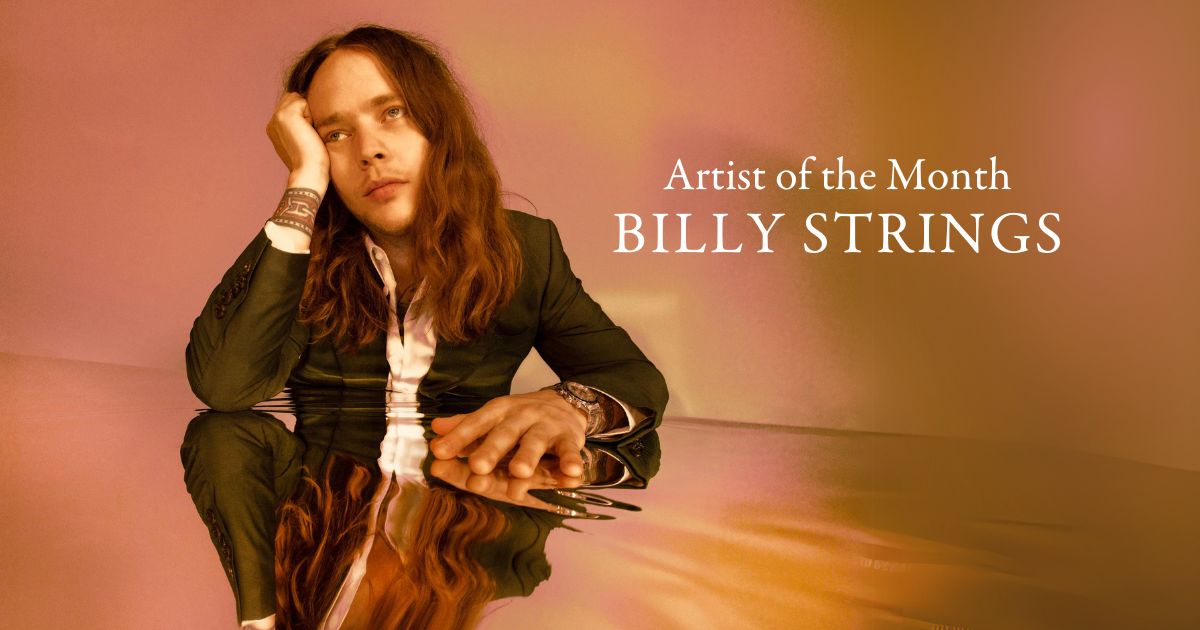

The reason, I think, is that, as BGS Editor Justin Hiltner puts it in his Artist of the Month reveal essay, “the most innovative and revolutionary aspects of Billy Strings and his version of bluegrass are not what he’s changed, but what has stayed the same.” When the BGS team invited me to have a chat with Billy for Artist of the Month, I figured it was, among other things, an opportunity to dig deeper into that idea – and so I did.

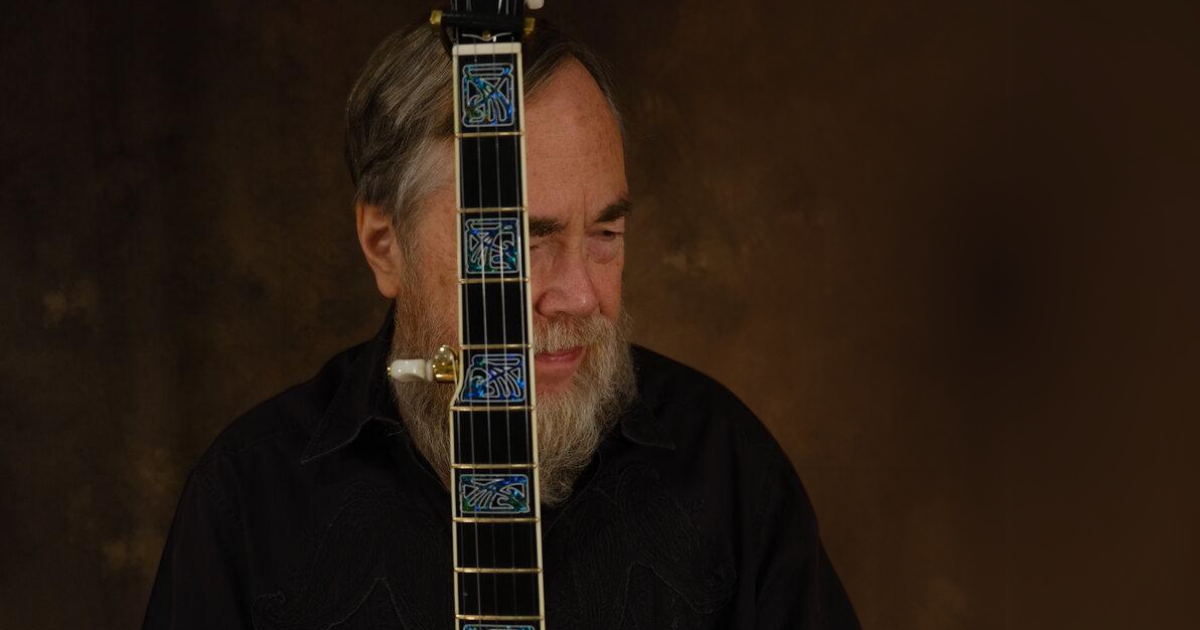

Together, we talked about recording Highway Prayers, about working in a band, about writing songs and making set lists. We talked about a number of things, but somehow always wound back up, again and again, at the endlessly rewarding music of Mac Wiseman and Larry Sparks, “Riding That Midnight Train” and “Cumberland Gap,” “Uncle Pen” and more.

Does it get any more bluegrass than that?

You didn’t record Highway Prayers all at once, did you? Wasn’t it recorded over a while?

Billy Strings: Right. We started in January out in LA at EastWest Studios, with Jon Brion the producer and Greg Koller at the helm as engineer. We recorded a few tunes out there. I really love what we got sonically, but I just don’t know if being in LA while trying to make a record was right for us – we were right downtown in freaking LA, man. I felt like, “What the hell am I doing out here in this big city where all these movie stars are, trying make a record?” I was working with Jon [Brion], who is a genius, that’s where he likes to work and the sounds we were getting were awesome and everything was cool, but I think it was also at a time where I was wanting to get the guys together without a producer and just throw stuff at the wall.

So we threw a makeshift little studio together and brought in Brandon Bell, and that’s where we recorded a good bulk of it – just threw up a couple of mics with a little lunch box of pre-amps and went for it. We would sit there and work a song out and then go upstairs and cut it. The great thing about being at my house was, it’s like there’s no authority figure there and it doesn’t feel like a studio – it just feels like we’re at band practice. And if you wanted, while somebody’s trying to do a overdub or something, you could go for a bike ride. Just that in itself was mentally freeing.

I will say that the tones we were getting out there with Jon were unquestionably better to me. But I’m kind of in the spot where I’m just, like, “Does it really matter?” Well, even if most people listen to music on their damn phone, it does matter. That’s how you make a sound that can evoke emotion. But also, as a bluegrass musician, any time we get with somebody or something, it’s like, “We should record you guys on these old ribbon mics and straight to tape with no edits,” and it’s just like, “Well, dude, it’s 2024.”

I feel like in some ways when people do that, they’re kind of privileging the process over the result, when the result is what people are gonna hear and what they’re gonna relate to.

Yeah, I’m just chasing something and I’m not trying to think about it too much. I read something in a book the other day, it’s called Blues and Trouble, by Tom Piazza. He says that sometimes you can push an idea up a hill, and you gotta push and push to get it to the top of the hill, but sometimes an idea gets going and you have to run to keep up. That’s where I like to be – you know what I’m talking about as a songwriter – when it just kind of falls out. Those are the best ones, you know, and quite a few of these songs just rolled off the page. Like “Be Your Man,” for instance, I wrote it in 20 minutes; it just came out. Of course there are other ones you have to work hard on, but, man, those – I just love when they show up like that, it almost feels like you just siphoned it out of the ether. Who wrote the song, you know?

That’s something that I’ve heard a lot over the years from a lot of great songwriters: it’s just like pulling it out of the air, and it kind of falls right in there. When you’re in that zone, you can’t hardly beat that.

No, you gotta keep going with it, you know. It’s hard to get in that zone, and like I said, it’s rare for me, it might only happen a couple of times a year that I write a song like that. That’s how “Dust In a Baggie” was. I wrote it in 30 minutes at work – I didn’t even have a guitar, I just had the melody in my head and a little notepad. I was cleaning rooms at the hotel and I sat there and wrote that. That’s still how the song is today, you know, it was just… it was done. Finished.

Let me ask you a little bit more about your process more generally. What’s the role of the guys in the band? You know, in the bluegrass world, at one extreme you’ve got the Jimmy Martin style of bandleader, which is, you know, “This is my sound, and this is how you’re gonna do it, and I will tell you what you need to do and show you what you need to do.” Then, on the other end, you’ve got somebody like Bill Monroe or J.D. Crowe, who says, “I brought you in to do your thing and let’s see how it fits together with everything else going on there.”

I very much lean towards the latter. I’ve got such amazing musicians that I’d be stupid not to listen to what they’ve got to say, you know? They’re so amazing and each one of them has their own strengths. So it’s a good mixture of like, I’m the band leader, kinda what I say goes, but I also take into consideration everything that the guys say. Sometimes I really need their advice and ask for it– like, for instance, most of the time I write the set list, but sometimes … I’ll go to the front lounge and say, “Hey, what do you guys wanna play tonight?” And then some ideas will come at me.

They’re there when I need them and they also don’t take anything personally when I say, “Hey, no.” It just depends, because sometimes it’s touchy when you write a song and somebody else wants to try to change it. But sometimes, if you hear them out, the idea that they come up with is way better. It just takes you a second to see what they’re talking about.

What you said about Crowe, bringing people in to do their thing, that’s really what I want. I don’t wanna be the dictator. I wanna be somebody who’s in a band. My whole life, my friends have been my family, especially when I was a teenager and started playing in bands. The word “band” means a lot to me. It means my brotherhood, you know, my closest friends and family.

That leads me to something that I don’t know if I’ve ever seen anybody else talk to you about this. You’re constantly bringing new material into the band – not originals, but older songs, old bluegrass songs. You’re always refreshing the repertoire. Are you just listening to old stuff all the time and hear something and say, “Man, that’s cool, let’s start doing that”? How does it work?

There’s a lot of songs in my head just from growing up playing bluegrass and we still haven’t scratched the surface of it. You know what I mean? Like, one night I’ll just be thinking of my dad in the old days, how we used to pick down around Barkus Park, and I get feeling sentimental or something and all of a sudden we’re gonna play “Letter Edged in Black” or whatever.

There’s just a whole well of tunes to pull from the bluegrass songbook and I like to mix it up. Like, if we did “Cumberland Gap” last time, then let’s do “Ground Speed” this time and if we did “Ground Speed” this time, next time let’s do “Clinch Mountain Backstep.” And then sometimes you play a tune and it feels good, so then it will stick around – like we’ve been playing “Baltimore Johnny.”

I guess having the guys in the band that you do helps, because a lot of them already know those tunes – or at least have some idea how they go, so you can work something up pretty quick.

Yeah, and they’re quick learners. Most of the time I wake up at the hotel and I’m stressing until I can write a set list, until it’s finished. Otherwise I can’t take a nap, because it’s a puzzle every day. There’s so many people that come to every single show of ours and we see the same people in the front row every night. I just don’t wanna feed them the same thing for dinner. I wanna mix it up.

Sometimes it takes two or three hours to make a set list. I’m doing it all on my iPad, so I’m not actually crumpling up paper and throwing it in the waste basket, but that’s what I’m doing. I’ll make a set list and I’ll go, “Oh, fuck that, that’s garbage.” And then eventually I’ll land on something that I feel is suitable or whatever. But it’s a puzzle every day. And then usually there will be a song or two on there– back in ’23, or maybe ’22, we played a new song every single show of the entire year. Every set that we played, we debuted a new cover. That was a task; once we got halfway through the year, it was like, “We gotta keep it going.”

So these days, it might not be every single show that we’re having to learn a new song, but we’re definitely having to refresh on things and arrangements and stuff. Every day before a gig, if we go out on stage at 8:00, then 6:45 or so we’re getting our instruments and sitting down and we’re starting to talk through some shit. Sometimes we’re learning these songs. And then sometimes we go out there and wing it. I like to be in that space, too. A lot of times, if we over rehearse things and think about it too much, somebody will fuck it up. But if we just get the basic idea down and go out there and somehow believe in ourselves, then we get through these songs.

Leaving the covers aside, I was reading a review of Highway Prayers and the guy who wrote it seemed almost baffled by the fact that it’s really a bluegrass album. And it is, from “Richard Petty” to the opening song that you wrote with Thomm [Jutz], to “Happy Hollow” and even “Leadfoot.” These are songs that, to me, are almost super-traditional in the forms that they use and the melodies.

Do you feel like your ear is kind of trained enough to feel comfortable with reusing folk materials, for lack of a better term? Like “Leadfoot” has this “Lonesome Reuben” kind of sound to it – but it’s not “Lonesome Reuben,” either. That’s gotta enter into your process a lot, I would think.

Not consciously. I grew up playing bluegrass and sometimes when I’m trying to write a song, that’s just how I think about it. When I first started writing, back when I was 16 years old, I would just rewrite “Riding That Midnight Train” or something. Not trying to, I would just write a song and then I would be like, “Oh, fuck, this is just ‘Riding That Midnight Train,’ it’s just the same melody. I can’t even call this my own song. But now, with a song, I show it to the band guys and they’ll say, “I don’t know, I think it’s your tune.”

I’m just trying to chase the idea, and not get in its way, and not let anything – especially from the outside world – into my brain to influence my direction. When I’m writing something good, it’s like I’m trying to write in my diary or something – or like I’m trying to write a bluegrass song that is [reflective] of my childhood and my love for the music. It’s that sentimental feeling that I get when I hear bluegrass music, that I love it so much, that it reminds me of my childhood. That before I knew anything dirty about the world, there was this love for bluegrass music and that’s the kind of music I wanna make.

I’m a bluegrass man. You know, we do all this other stuff, and I write other songs too, but at the core of it all is a bluegrass musician who was fed Doc Watson and Bill Monroe and Larry Sparks. So that’s the stuff that I like. I’m still listening to the Stanley Brothers all the time. I’ve listened to this shit my whole life and I still haven’t heard it all, you know?

You could do pretty much whatever you wanted, and yet you are still, at the core, playing bluegrass music.

What’s authentic? You know? I’m trying to not lose myself to this fucking big monster, you know what I mean? Because, yeah, I could get a drummer and pick up my electric guitar. I could put on a cowboy hat and join that whole bandwagon, too. But that’s not me and it’s not true. I don’t care about that shit. The more that I’m in this industry, the more that I’m just trying to stay true to myself and my music, because I see past all the bullshit and see past the glam of it. And I’m so grateful – so, so grateful – to have a fan base that will allow me to just wear a pair of blue jeans on stage and play three chords and the truth at them.

I feel like if I went and changed it up too much, then I might lose a bunch of those folks. And that’s hard, too, because sometimes I feel like we need a drummer. We’re in these giant arenas, it’s like, “Man, if I had a drummer and I could pick up the Les Paul, we could just fucking chop heads.” And I do enjoy that, too, because that is part of who I am. When I got out of playing bluegrass so much, when I was a kid, I played some electric and some Black Sabbath and shit – so there’s some of that in there.

But what I play is what’s in my heart, man. And that’s why I’m still playing Mac Wiseman songs, and there’s something – it’s almost like a freaking kink or something. I just love it so much. I love playing “It Rains Just the Same in Missouri” to a big crowd of people, or “I Wonder How the Old Folks Are at Home, or “The Baggage Coach Ahead,” or any of these old [songs].

You get out on the big arena stage like that and you play “Uncle Pen,” it’s like, “Fuck, yeah!” It’s kind of like just force-feeding these people bluegrass, and I love it, you know.

(Editor’s Note: Continue exploring our Billy Strings Artist of the Month content here.)

Photo Credit: Dana Trippe