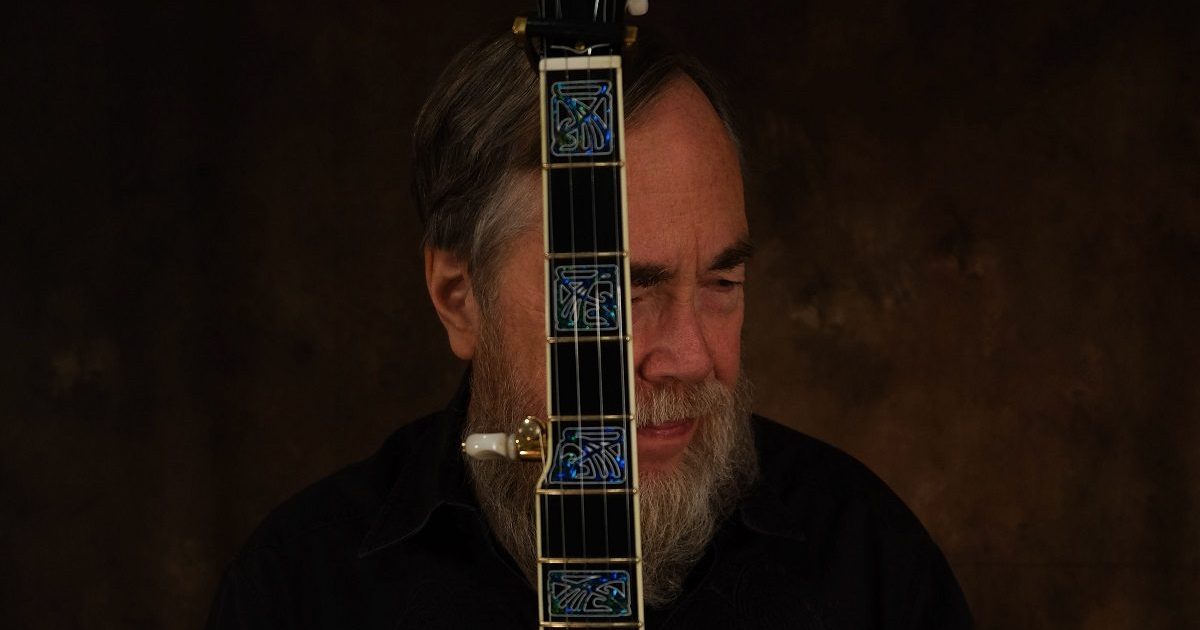

Some years after the late great John Hartford passed on, his daughter Katie Harford Hogue wound up with his archival material in her basement in Nashville. It was a huge collection, a lifetime’s worth of recordings, books, instruments, notes, stage outfits and all the rest. So she dutifully began wading through everything to sort, organize and catalog it all. And she would come across notebooks with numbers on the cover, which she set aside – 68 of them all together.

“It can be a pretty heavy task to go through someone else’s things like that,” Hogue says now. “And I was not sure what they were at first. But we were able to piece together the puzzle and figure out what these were: They had been his creative journals.”

Representing decades’ worth of raw material, the journals contained nuggets straight out of Hartford’s musical mind. There were some transcriptions of old tunes by other artists, but the vast majority of it represented original music composed by Hartford himself, amounting to several thousand tunes. It was a trove that yielded up a couple of projects that have returned Hartford to widespread attention coming up on two decades after his death.

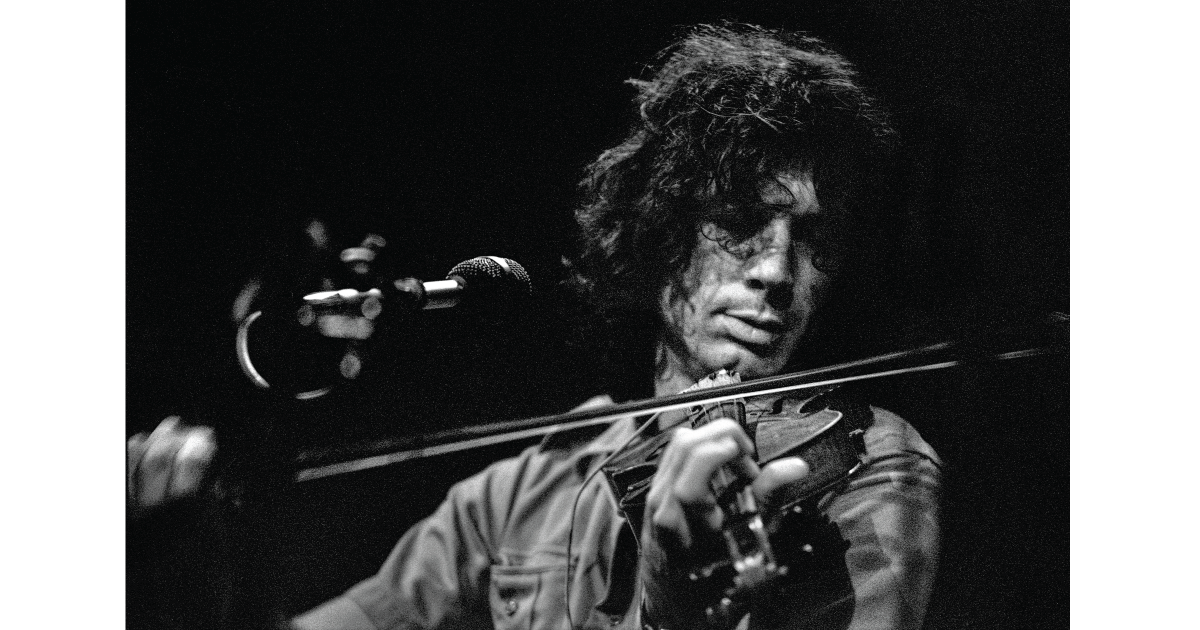

First came a 2018 book, John Hartford’s Mammoth Collection of Fiddle Tunes, featuring transcriptions of 176 compositions from the journals as well as Hartford’s own illustrations plus writings from Hogue, musicologist Dr. Greg Reish and others.

That led to an accompanying album, The John Hartford Fiddle Tune Project, Vol. 1, featuring an all-star cast of players recording 17 of the archival Hartford songs.

Even though it was independently released, The John Hartford Fiddle Tune Project is up for a Grammy Award in the category of Best Bluegrass Album, alongside Billy Strings, Danny Barnes, Steep Canyon Rangers, and Thomm Jutz.

“Winning would mean a lot,” says Hogue, who is credited as co-producer with Matt Combs. “But I certainly feel honored to be considered, especially in a field like that. The fact that there’s something new that has people paying attention to my dad’s work again is wonderful. Mind-blowing, even. It’s a side of him that a lot of people did not know about, another dimension. I love being a part of that.”

Hartford was no stranger to Grammy Awards, going all the way back to his mainstream breakthrough with “Gentle on My Mind.” Reputedly inspired by the 1965 romantic epic Doctor Zhivago, Hartford wrote and recorded the first version of “Gentle on My Mind” for his 1967 album, Earthwords & Music.

Yet it was Glen Campbell’s version from later that year that put “Gentle on My Mind” on the map. Industry lore has it that Campbell made what he thought was a demo, complete with yelled instructions to the Wrecking Crew studio musicians. Campbell’s producer Al De Lory cleaned it up enough to release as-was. And even though it barely cracked the pop Top 40, “Gentle on My Mind” never left the radio. In 1990, BMI rated it as the fourth-most played song in radio history.

Along with setting Hartford up financially, Campbell’s “Gentle on My Mind” cover won Hartford his first two Grammy Awards. He won another for 1976’s Mark Twang, an album inspired by Hartford’s riverboat experiences on his beloved Mississippi River. And his final Grammy was awarded posthumously, for his contributions to the landmark soundtrack for the 2000 Coen Brothers slapstick epic, O Brother, Where Art Thou?

O Brother’s surprising popularity launched a bluegrass revival and also put a luminous bookend on Hartford’s career. He emceed the Down From the Mountain show at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium on May 24, 2000 (filmed by D.A. Pennebaker for the concert film of the same name), in which Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Ralph Stanley and other stars from the soundtrack performed. The soundtrack was just starting to take off a year later, on its way to topping the charts and winning a Grammy for Album of the Year, when Hartford succumbed to cancer on June 4, 2001, at age 63.

“He didn’t get to see all of that, but he would have told you that the coolest part of that movie being popular was that it put an old Ed Haley tune in the forefront,” Hogue says. “There’s a campfire scene with a lonesome fiddle playing, and that was my dad playing the Ed Haley tune, ‘I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow.’ That was always his goal, to highlight the old-time music and fiddle players he loved so much. I don’t think he would have taken any of the accolades for himself.”

The Fiddle Tune Project album liner notes include a quote from Hartford himself, something he told Matt Combs once: “If we play our cards right, we can fiddle all day and on through the night.” That play-all-night-play-a-little-longer spirit animates the album, as played an all-star cast including Sierra Hull, Ronnie McCoury, Alison Brown, Tim O’Brien, Brittany Haas, Noam Pikelny and Chris Eldridge from Punch Brothers and Hartford’s old bandmate Mike Compton.

However, Hartford himself is the real star, in absentia, via the 17 songs pulled from the 2,000-plus in his journals. Hogue calls it a celebration of his creative process.

“Creativity with him was like a faucet he could never turn off,” Hogue says. “His journals are full of weird late-night thoughts and ideas he’d jot down, and then go back and try to work into something. He was very prolific and would go down rabbit holes very quickly. His journals have a lot of stream-of-consciousness writing where he was looking for different ways to come up with songs. He was a very open free-thinker.”

Combs oversaw recording at Cowboy Arms Hotel and Recording Spa, a Nashville studio formerly operated by Jack Clement. It is the studio Hartford used to make his 1984 album, Gum Tree Canoe. The project was funded by a Kickstarter campaign that raised more than $33,000 from 468 contributors. As the Vol. 1 in the title implies, there will be future volumes if only because more musicians wanted in on it than they had room to accommodate on just one record.

Indeed, tending to her father’s posthumous legacy has turned into quite an ongoing project for Hogue. Hartford left behind so much material in so many wide-ranging areas that the family donated parts of it to four different institutions. The Herman T. Pott National Inland Waterways Library at the St. Louis Mercantile Library is where Hartford’s photos, journals and research pertaining to the Mississippi River wound up.

“That’s where the papers of all the river people and mentors my dad grew up with are, so it already looked like his office on steroids,” Hogue says. “So that was a no-brainer for everything of his related to the river, from when he had his pilot’s license. Had he not been a musician, he would have been a boat pilot up and down the river. That’s what he really loved. It was his passion.”

Putting together these projects has been therapeutic for Hogue, who was raised by her mother after her parents split when she was very young. She didn’t see much of her father during her childhood, and there were long stretches when she mostly heard from him when he’d mail her copies of his latest album.

“I still remember opening the mailbox one day and finding Aereo-Plain,” she says, referring to Hartford’s 1971 hippie-bluegrass classic.

For all Hartford’s success, his daughter still didn’t realize his stature until relatively late in his life — especially from all the visitors who came to see him at the end. That carried over to when she was dealing with the archive that yielded up the book and the album.

“There’s a lot to sift through in a process like that,” Hogue says. “The public sees the figure and the persona and hears the music, but there’s so many different dynamics behind that for friends and family. When you lose a parent, it’s like the world comes to a stop and there’s suddenly a period at the end of everything they were. There’s so much joy, anger, frustration, confusion. Going through all his things this way made me able to see the human side of him, which was healing. It’s been a way to say, ‘Hey, Dad, we’re good. I did this because I love you.’ There’s a lot of joy in these songs. They just make you want to dance, and his spirit comes through. I love that. I’m thrilled to be able to have this with him, even though it’s posthumous. A father-daughter project, where he’s here in spirit.”

Photo credit: Charles Seton