(Editor’s Note: This conversation between Black Opry co-director Holly G and BGS executive director Amy Reitnouer Jacobs was moderated by journalist Jewly Hight and marks the culmination of our Artist of the Month coverage of Black Opry. Find more on Black Opry here.)

“I just wrote this down, because I need to look at this every single day,” Amy Reitnouer Jacobs informs Holly G while scribbling on a sticky note: “Your name’s on there. You get full credit.”

Holly G, the creator of the Black Opry, has just dropped a gem of practical, principled wisdom that she’s developed through dealing with event organizers, entertainment companies, and institutions who expect her to lend them her presence, while withholding her critiques of the racial biases baked into how they operate. Her hard-line posture? “My participation is not an endorsement.”

Even in a matter as small as pinning that sentence to her wall, an act we observe on the Zoom screen, longtime BGS leader Reitnouer Jacobs knows well the importance of receiving proper credit, and compensation, as a persevering music industry dreamer and doer who’s also a woman.

These two founders of influential, community-shaping music platforms have crossed paths on plenty of occasions, but they’d never before stopped to compare notes. Their work addresses the insularity of music scenes in different ways, Holly G’s taking aim at country music’s exclusion of Black performers and Reitnouer Jacobs’ at bluegrass’ fierce protectiveness of perceived threats to its purity. Still, the similarities between what they’ve experienced, how they’ve responded and who they’ve paid attention to pile up rapidly in our Zoom conversation.

By the time we’re through, Reitnouer Jacobs signing off from her Los Angeles home office and Holly G abandoning her laptop to check on guests she’s invited to a Black Opry mixer at a rented house in Nashville, they’re feeling a significant overlap in their labor and making plans to actually, some day, do something together.

Jewly Hight: You both had careers completely outside of music and then your own fandom drove you to start blogs and put your stakes in the ground in the digital space. I was thinking back to the crossroads moment that you each must’ve reached where you were starting to get a response and see other ways that you could decide to get involved in those musical spaces. What really mattered to making the decision to expand each of your missions?

Holly G: I don’t feel like it was a decision for me. I’ve never consented to any of this. [Laughs]

I feel like it really, really shifted right after you interviewed me for the first time, and that article went up on NPR. That’s when everybody was like, “Oh, this is serious.” And because what we were actually doing was so vague, because I didn’t have a plan, people were just asking me to do everything; I had never said what I could or couldn’t do. By the time people started asking me for heavier lifts, I had already met these artists and I was so invested in the artists and seeing how hard they worked. I was like, “I’m never gonna say ‘No’ to anything. What could be good for them? What could push them forward?” A lot of it just went over my head, ‘cuz I was just saying “Yes.” And then I was like, “Oh shit, how did we get here?”

Amy Reitnouer Jacobs: That actually really resonates, when you said once you started meeting the artists that suddenly you saw where the needs were. That was a huge shift for me. I mean, I got into this as a fan, but I really didn’t think about writing about this community, this genre until I started to become friends with the artists that were involved and get to know them and become kind of part of their circles.

I think there was definitely a moment of, “Oh wait, you’re not being served? We’ll work on that. We’ll start covering that. Wait, you also are not being represented over here? Let’s cover this, too.” I’ve had to learn how to say “No” over the years, but my immediate instinct is always to say “yes” and then figure it out.

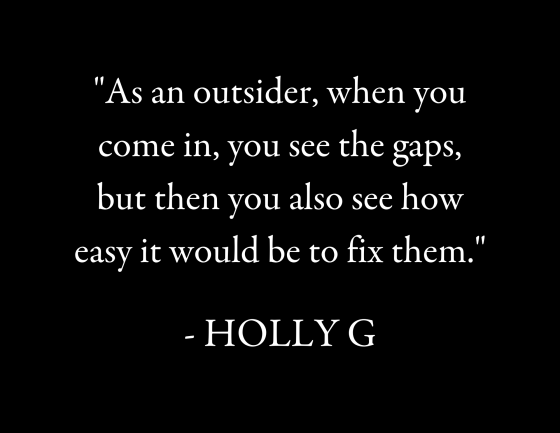

HG: My rule is if it’s not gonna negatively affect my mental health, then I say, “Yes.” That’s where I draw my line at. As an outsider, when you come in, you see the gaps, but then you also see how easy it would be to fix them. Sometimes people don’t know or they’ve just never been asked to do the right thing. But if you can have somebody [involved] that’s not an artist, they’re like, “There’s no ulterior motive.” Nobody thinks that I’m asking for Black people to get on stage so that I can go sing, ‘cuz we all know I can’t.

JH: It changed everything when you each were put in close proximity to artists who were working toward things, and had ambitions and scenes that they were part of or wanted to be a part of. What did it actually look like to turn your desire to help into strategies?

ARJ: When you’re actually given real responsibility that you have to show up for and deliver, suddenly it all becomes a lot more real. I had to go through a perspective shift.

I would say producing the IBMA Awards was a really big thing, because it was suddenly very, very real. It wasn’t just me being like, “What the fuck, IBMA? Come on, get your shit together.” It was like, “Now they’ve handed me something that I can make a change in, and I have to do it and I have to do it right. And I have to do it to not only to an industry standard, but to the personal standards with which I wanna move forward and I wanna see this industry move forward.” So that and doing a [BGS] stage at Bonnaroo, doing a lot of the curatorial stages, like what Black Opry does as well. I think when you suddenly are putting this out in a packaged way for everyone to see, it kind of makes it all a little bit more real.

HG: It’s really cool to hear your perspective, because as you know, there’s not a lot of people who have journeys that are like ours.

When you say going from yelling about it to being in the room and they’re asking you what to do about it is a very weird feeling. Especially because I wasn’t criticizing [the country music industry] with any intent for anybody to ask me any questions. It’s like going into somebody’s house and you’re like, “I hate this wall color.” And they’re like, “Okay, well paint it.” And I’m like, “Well, I’m just giving you my opinion.” You know what I mean?

JH: There’s a big difference between critiquing from a distance and being handed a thing and asked to work on changing it. That raises the stakes.

HG: I was speaking before I knew what I know now, but as a fan, you’re not thinking about how the industry works. You’re just seeing the flaws and you’re like, “Well, this doesn’t make any sense.” But you’re not ever thinking with the expectation that you’re gonna have to be the one to fix it.

When we started booking shows that we were actually getting paid for, as soon as money started coming in, I was like, “Whoa, that always feels like a big responsibility to me.” Because it wasn’t a career aspiration of mine, not in any real substantial way. Once money started coming in, I’m like, “Number one, this needs to be distributed fairly.”

It took me a long time to take money from shows. My agent would yell at me all the time. She’s like, “Why aren’t you paying yourself?” And I’m like, “Well, because I wanna make sure the artists get paid.” And she’s like, “This is a business. You’re doing work. You have to pay yourself.” Finally, after exhausting myself and realizing that the exhaustion was because of the work that I was putting into it, I’m like, “Okay, I’ll pay myself.”

ARJ: Holly, that really struck a chord with me, what you said about the money. When those stakes came in, it was like, “Oh, this isn’t just a blog anymore.” There is something on the line and there’s someone investing in me and in this idea, too, and they’re investing with the trust that I’m gonna do the good work.

It took me over five years not to start necessarily paying myself, but to start prioritizing myself and considering myself part of that package, rather than just putting everything I had into it, at the sacrifice of personal life and sometimes physical and mental health and financial choices.

HG: I wouldn’t have made it that long. But you know why, though? I got to that point so much quicker, only because a lot of the things that people were asking me to do were so emotionally draining, like to constantly go through racial trauma and explain myself. That shit is so exhausting. I very quickly was like, “What am I getting out of this?” I do not mind taking money from that at all.

I still don’t think that I’ve seen the changes I would like to see overall – in any facet of the industry. But what I have seen is individual artists’ lives completely changed. They can tour in a different way because of the way that we tour. Our tour minimum is $400 per show. So they can go out and play a show with us for $400, and that means that they can go to that area and play a couple other bars where they might not really get paid anything, but they’ve gotten something to get up there to help them get a little bit of a leg up.

JH: You were talking about learning how things work in the industry. I imagine that part of that involved coming to understand the established pipelines that exist in country music, in bluegrass, and in roots music, how they work, who they work for, and who they don’t work for. Realizing that they are not built in a way that is meant to serve everyone. You didn’t just accept that those established models are the only options. What kind of relationship do you each have to the industry? And where do you place your trust?

HG: I don’t trust anybody. My mission is to serve the artists. My personal feeling is that we need to build systems outside of what exists and so that we can build it in a better way. Because you’re not gonna go into an institution that’s been around for a hundred years and fix things that have been wrong for a hundred years. It’s not gonna happen, especially not gonna happen quickly.

However, it is not my right or privilege to tell an artist that they shouldn’t participate in the industry. So that being said, I have to work in parallel. Yes, I’m building things, but I also have to interact with the industry in a way that I can advocate for the artists that wanna participate in that.

And so when I do interact with the industry, it’s basically like, “What can I get out of you?” Because I know this is how they look at me. And so my first thing is, “What do you have that I can get that will serve me, that will serve my artists, that will serve my mission and my brand?” If what I can get from you feels like it’ll be worth whatever it is that you want to take from me, then I do it. But if I can’t get something back, that’s gonna make that exploitation worth it–because that’s what the whole industry is, exploitation–then I just move on.

ARJ: It took me a while to realize that, when I was talking about not prioritizing myself and not paying or taking care of myself, that in doing so I was actually falling into the trap that so many of these institutions had established of not paying women the same amount, not paying us what we’re worth.

I know that there are industry standards of not paying Black women what they’re worth, even less. I thought for a while that just by being part of this panel or whatever, I’m doing the right thing, ‘cuz I’m there and I’m representing something new and different and fresh and modern.

But by accepting an honorarium that I would find out later was less than some of the male names also appearing at a conference, I was falling into the same trap. It still enrages me, still gets me mad and so I feel like now I can be in, but not of a lot of these institutions. I’m happy to work with them if they’re gonna pay up and have us there for a reason, but I’m not going to serve them. I am not going to help, assist or fix what is institutionally wrong.

That’s partially why I’m really proud that BGS has continued to be independently run and owned this whole time, because we don’t answer to anybody, and nor do I plan to.

HG: I’ve pissed quite a few people off, ‘cuz I’ll work with them, but then after it’s over, they do something else. Then I criticize them and they’re like, “But wait, you came and did a panel for us.” And I’m like, “My participation is not an endorsement.” My presence does not mean you are off the hook for everything that you have done or going to do in the future. And so it has been interesting to watch them fall apart as I continue to criticize them and to see which ones come back after that. And that’s how I can tell whether or not they actually wanna do the work. If I criticize you and you come back for more, that tells me how you wanna do the work. That’s been a really good filtering tool for me.

JH: Even with the healthy skepticism that you’re each describing, you’ve managed to execute really massive events and partnerships. How do you make those decisions about what powerful people or institutions are worth partnering with?

HG: There’s no science to it, I feel like, because the other thing is there’s good people at bad places and that’s across the board. If I can find the good people at the bad place, then I’ll work with those people. And that’s just kind of how I do it.

I’ve gotten to the point now where I tell them that part up front: “This does not absolve you from anything that you do. I’m still gonna speak up.” One of the things that I’m afraid of happening is for people to look at what I’m doing and be like, “Okay, well she got in the room now, so I guess everything’s fine. She’s not speaking out anymore.” I don’t want it to look like I’ve closed the door behind me. If you can’t handle that, then we don’t have any business together. And as long as you find those good people, they’re gonna understand that and they’re gonna push forward anyway.

And sometimes because of that, I’ve had people tell me, “Please continue to criticize us, because that’s the only way I can get my bosses to do [anything] is when you won’t shut the fuck up on Twitter.”

ARJ: For the most part, I find that there are really good people on the ground, doing the work and for me, a lot of it just comes down to – I don’t know – intuition. It’s not necessarily a financial thing. It’s not necessarily a visibility thing. I think that’s kind of my unofficial business strategy, which is probably not something that they teach you to do when you have an MBA. But I never planned to get into this job to begin with, so I just go on intuition and I work with people I love. I return to things that I love and places that take care of our artists and take care of our community and take care of us. Those are the people that I will continue to invest in and go back to.

JH: Bluegrass, Americana, roots, and country are so often spoken of as though they are strongholds of authenticity insulated from commerce, to an extent. But we know that all of these spaces are inherently commercial if anyone’s trying to make a living off of them. So as people who are very invested in building community where it doesn’t exist in the ways that it needs to, how do you hold those two things next to each other?

HG: I do not. I think that also the whole conversation about authenticity is bullshit. It’s a way to move the goalpost, so that they can keep the people they want in and keep the people they want out out: “That’s not real country. That’s not real Americana.” It doesn’t fucking matter, because what makes it real is usually who makes it. If they look at somebody and they recognize that person as somebody that they want in that space, they’ll accept anything. It doesn’t matter what it sounds like if it comes from the right person. It’s a tool that they use so that if somebody comes along that they don’t feel like fits in because of their gender, their sexuality, their color, whatever it is, they can then say, “Oh, well then it’s not real X, Y, Z,” and they can get away with it.

JH: I also want to get at how you’re acknowledging that this is commercial, but also insisting that building community matters. How do you do both at the same time?

HG: Very easily. ‘Cuz you do things where you bring people together behind the scenes when you know everybody’s in town. That’s what we do. We get a house and we make sure everybody has somewhere to come together. But when you ask me to show up at the thing, I’m gonna ask you for a check. You’re gonna pay me to have official participation, but behind the scenes, we do things that build community. I feel like that’s all relative, right? So I’m not gonna go to a festival that’s just starting up and be like, “We need $20,000.” But if you’re paying everybody, make sure you pay us what’s fair in relation to what you have. So it’s just figuring that part out, but also always making sure you’re asking for it. I’ve learned to ask upfront, “What’s your budget?” Because that way I know where the conversation is gonna go.

JH: That’s sort of like reverse gatekeeping, in a sense. When you put together events or decide to gather artists to participate under the name of Black Opry, some of those things are for the public, outward-facing performances. Then there are things you do, like rent this house and invite who you want to be here, where you’re creating a safe, private space.

HG: The way that I curate the shows is more community driven. I try to pair up artists, especially if they’re traveling for a tour, that I feel like their personalities either mesh or there’s something in their story that I know would [connect] with each other or like things like that. It doesn’t matter if two artists’ music would sound great on the same bill, if those people don’t connect. I mean, I can put people together that sound completely different. I’ve had Jake Blount and Kentucky Gentlemen on a show together before, and they all were so excited to be with each other. The best part of our shows is usually the green room. That’s kind of a private, intimate space.

ARJ: You keep saying a lot of parallel things to what we do. I didn’t realize how parallel some of our experiences have been, and it just makes me love you more, Holly.

So much of what we’ve done over the years, it will never be public facing and the public will never even know about, because it’s not why we do it. And I think it’s what makes artists continue to come back to BGS events or wanna be covered on the site. Artists that, 10 years ago, I would’ve never thought I’d ever get the time of day from will say “Yes” to things because we put them first and we have given them a safe and fun and communal space to be together.

When I started BGLA originally, and then BGS, I wanted it to be this place for modern fans, for younger fans, for all fans that I didn’t think were being served or represented. I think for a while I was really susceptible to this yarn that they were spinning of, “There’s just not enough women in bluegrass. There’s just no Black people in bluegrass.” And I’m like, “Wait, I don’t know if that’s right.” And then the more you dig and the more you get involved, you’re like, “These communities have been here the whole time.” This is not only about creating community, this is about connecting community. This is about bringing communities together, representing them, and, and connecting the dots, whether it’s a digital community or artists in a green room or in a house to hang out for a jam.

HG: It’s so funny, like how the parallels keep coming up. Cause people have asked me a lot recently in interviews, “How do you feel about this revolution in country music?” And I’m like, “It’s not a revolution. It’s recognition.” This has been here the whole fucking time.

JH: There are deeply entrenched perceptions about what the country fan base looks like that are based on the continual and artificial segregation of the industry. And there are equally entrenched perceptions of what a bluegrass fan base looks like, based on the fervent reverence for the models laid down by the first generations of musicians. How have you developed ways of speaking to audiences within audiences, those that have gone unseen and overlooked?

HG: I’m telling you, I thought I was the only one when I started Black Opry. It was more like a search and explore mission than it was like an intentional, “I’m gonna find these people.” Because as a Black person that loves country music, I promise you, anytime you tell somebody that, you get looked at like you just fell out of a UFO.

I was equally surprised when I found artists. I didn’t think there were more than five artists. I was like, “We got Mickey, Jimmie, Kane and Darius.”

There was so much passionate relief when people started seeing you and feeling seen. It still surprises me. And I’ll be honest: We still haven’t gotten to where we need to be as far as the fan base with country music. There are a lot more queer fans simply because there are a lot more white, queer people that like country music. So we’ve built up a really, really big white, queer fan base.

A big priority for me this year is how do we connect with Black fans? Because the Black publications and the places that Black people go to for music typically don’t interact with country music.

But I will say, every show that we’ve had that I’ve been to, there’s at least one Black person that comes up to me and goes, “I thought I hated country music, but I saw the word Black in front of it, so I came just to see what it was. ‘Cuz it sounded weird. And I loved all of this. If I knew country music was like this, I would’ve known I liked it.” We’re trying really hard to figure out how we get to those people in a more broad way and get more of them. We need our audiences to look like what we want our stages to look like.

A lot of the places I’ve been to, regardless of how kind the organizers have been, it doesn’t always feel safe. And so there’s no part of me that wants to advocate for Black people to come into some of these spaces, because I can’t guarantee they’re gonna feel good. At Newport [Folk Festival], we felt good, even with being all white people. It’s just the type of people that they attract; they’re good people. And so we’ve really, really been interested in seeing how we can figure that piece of it out, where we get more Black people to these spaces. But, I can’t consciously advocate for too much of that yet, because I need to see the institutions doing the work to make it safe.

JH: So it’s still very much an open question of how you find, reach, and speak to Black country fans.

ARJ: Something that we asked ourselves very early on was not how do we reach other Bluegrass fans or where do we look for other Bluegrass fans, but where are we not looking? Who are we not reaching? What’s gonna be unexpected in that crossover Venn diagram of fandom?

Because like you were saying, you felt like you were the only one. I felt like I was in a minority of young, urban dwelling, West Coast, female fans that didn’t grow up in the South, you know? I started the whole thing from a need to connect with other people. I mean, it really stemmed out of loneliness. But I realized that my online demographics wouldn’t have made me a targeted fan if I were launching BGS. Like, any advertising or any kind of targeting we would’ve been doing, I myself wouldn’t have been found.

I think we just realized within our first three, four years, we have to turn ourselves outwards and reject everything that we’ve been told of who fans are and who communities are. And we have to be looking elsewhere, and we’re continuing to do that. It’s a question that we’re constantly asking ourselves, and I think it’s something that you’re never done searching for because there’s always someone else who feels like they have been excluded or that they are alone in this, whether they’re a fan or a player, or they don’t know what they are yet.

I remember one of the first meetings that I had with some IBMA folks. They were like, “You keep putting up all this like modern stuff and this isn’t real bluegrass.” And I’m like, “You’re gonna tell me if a kid walks in to McCabe’s guitar shop in Santa Monica and wants to buy a Deering banjo and pick up a banjo for the first time ever because he watched a Mumford and Sons video, that you’re gonna tell him ‘No’? That you’re gonna say ‘No’ because that’s not bluegrass?” Fine, we don’t have to put a label on it. Why don’t you open up that door and introduce ’em to Earl Scruggs. Let’s take them down that rabbit hole and connect the dots once again for that person. How about we take their hand and help guide them through this expanse of everything?

JH: Since you mentioned a first-generation bluegrass icon, something that’s baked into country, bluegrass and roots music is venerating elders and creating canons. And that’s just as much about excluding people as it is about who belongs in the canon.

You each make elders very present in what you do. Holly, you recently advocated for the Country Music Hall of Fame exhibit that includes the Black Opry to also include its predecessors, Frankie Staton and the Black Country Music Association. Amy, you make decisions about meaningful coverage of multiple generations of performers all the time, and BGS just published an appreciation of an underappreciated first-generation picker, Gloria Belle. How do you think about ways of doing that better than you’ve seen it done?

HG: I don’t wanna make it seem like I strong-armed [the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum]. I would not have had a problem strong-arming them, but they were gonna do it anyway. So they said, “We’ve already sent a letter to [Frankie]. Calm down.” And I was like, “Oh, okay.”

I don’t really think of it so much in that light that you’re describing as I do that we don’t have a record of Black country music history. For me, it’s about building that record. There’s so many people – like Wendy Moten. Wendy’s been singing with Faith Hill and Tim McGraw and Vince Gill for years and years and years. She’s part of Black country music history to me, and we have no record of that. Nobody’s ever talked about it. It’s about finding those people from the other generations that have been doing this long before it was something I ever thought about, and making sure they’re included in this narrative so that whoever comes up after us doesn’t have to work so hard to find these things out.

There’s no reason I shouldn’t have known the things that I’m finding out now until I had to literally dig for them — and I get access to a lot of it, ‘cuz people see what I’m doing and will bring stuff to me. But it’s not out there and ready for the public.

ARJ: Building that history is such an important part. And because we have a platform, because we have this online record that we are building, that’s part of our responsibility, is to help maintain that.

Gloria Belle, like we heard about her passing and then we waited and there were no obits. And we were like, “Who’s, who’s gonna cover this? Oh wait, it’s us. We have to be the ones to cover it.” I should know that 10 years on. But I still get reminded time and time again, we still have to do the work.

I am not one to venerate folks who maybe don’t deserve it. But I do think it’s the same idea of you’ve gotta know the rules in order to break them. You have to know the history in order to figure out where you’re going and how to break out of that and how to change it.

JH: You both are continually adapting how you present and position what you’re doing. Do you feel like you have come up against the limitations of genre? And have you looked for ways to free your efforts up from those limitations?

HG: Yeah, that one’s been tough. I know what kind of music I personally like, and I like music that would be described as Country music by literally anybody who heard it. It’s usually not a gray area, the things that I like personally, and that’s what brought me to where I am.

But also, all of the artists that I talk to across the board say that genre is a harmful concept to their careers. And so it’s deconstructing that concept, but also realizing too that the advocacy, everybody needs all of this stuff. It’s not just people in this space. So it’s like, “Where do I fit into that?” Regardless of how I feel about anything, there’s enough people in [all parts of] the industry telling Black people “No.” And so if a Black artist comes to me and wants to work with us, I really don’t give a shit what they sound like. The answer is gonna be “Yes.” I’m never gonna turn anybody away. Right now where I’ve kind of settled is anybody can come and play with us with any style, but the advocacy work that I do is going to focus on country music spaces and institutions, just because that’s where my passion is and that’s where I see the greatest need for it. I do acknowledge that there’s problems across the board. If you look at the work that the Black Music Action Coalition does, they’re doing it across all genres.

I’m sure you get this too, Amy, where it’s like you want to work on the things that you care about and you like, but also once you have this level of responsibility, that really doesn’t matter anymore. It’s out the window. It should never be about what personal taste is. It should be about what’s best for the group at large.

ARJ: It was very confusing, I think, for folks to initially come to the site and realize that it wasn’t just Bluegrass. And our whole point was like, “This is pulling from the traditions of the genre that is called Bluegrass.” But that has taken on different incarnations and iterations over the years since it was established. I guess you could say, by the IBMA standards of 1945, you know, Bill Monroe. For a while it was about bucking people’s expectations when they would get to the site of what they thought they were gonna get versus what they were given on the website.

Then we made a very conscious shift to be called BGS. We still use the Bluegrass Situation. A lot of people still know us as that, but we have really made a conscious effort to switch over to BGS, in the long tradition of things like CBGB, or NME Magazine. After a while, it just becomes those letters. So that’s always been my hope, that it becomes more of an umbrella organization and that it’s not limited. I still lean on genre when I feel like it’s advantageous. Because at the end of the day, I’m not going to stop it from existing. It exists. It’s how certain people can identify what they want to listen to or how we search for a playlist, even. It’s just how things are organized, whether we like it or not.

So when I can be disruptive within those structures, I will utilize it. I know that I can make certain calls, or I can show up to certain conferences and I can make an impact within this community and I can have some kind of small change within this community. And that is what drives me, and that is when I’m willing to use genre, if it means that I can insert myself and continue to be a part of that and enact change.

HG: A lot of artists tell me that they feel like genre is weaponized against them. I feel like we have an opportunity to take that and then weaponize it back against the industry itself. Because it’s literally just a marketing tool, so you just have to figure out how to play the game so that it helps the artist more than it hurts him.