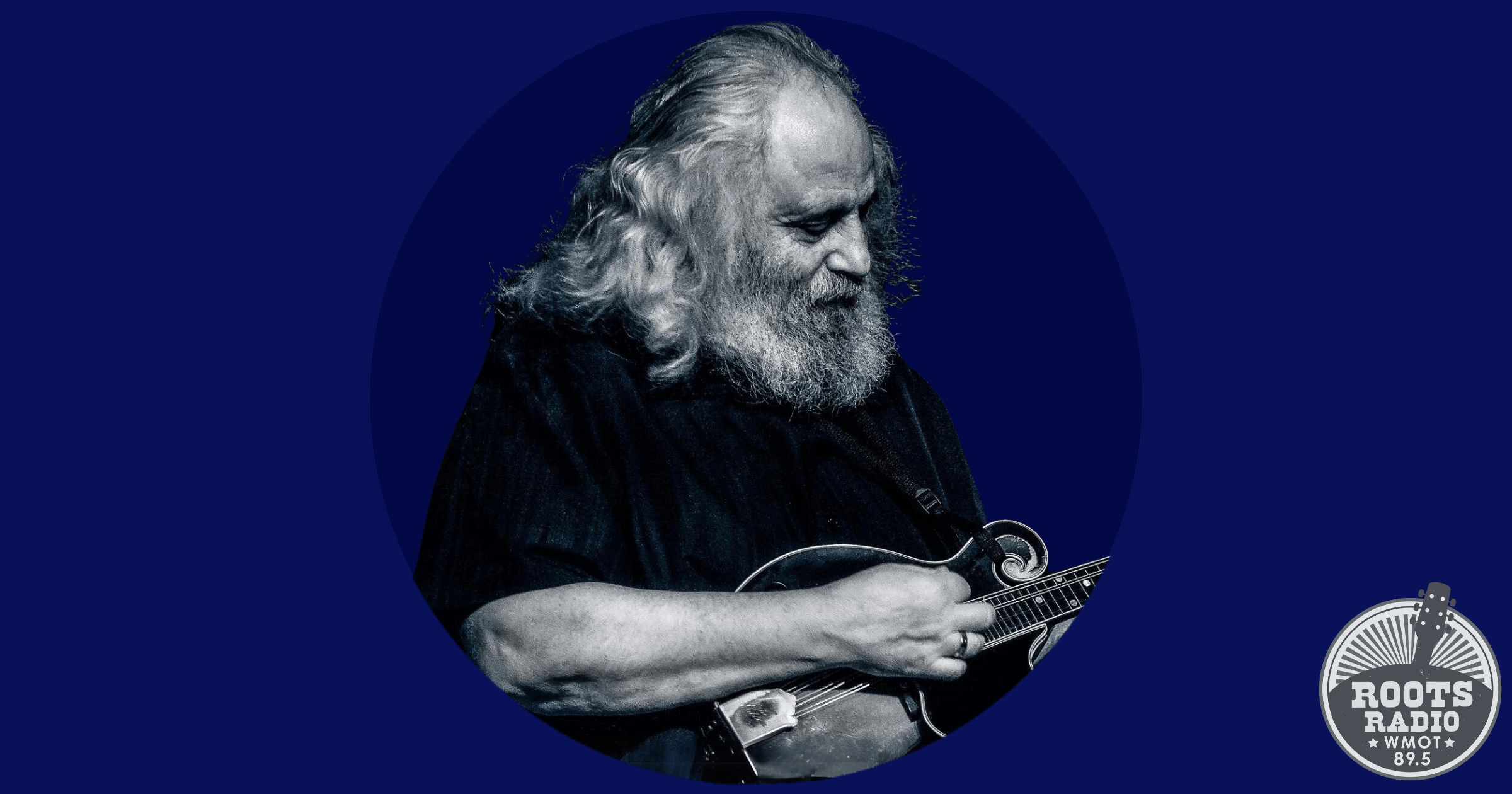

My conversation with Ben Garnett finds him at about a decade in Music City and in the swing of an album cycle for Kite’s Keep, the guitarist-composer’s second full-length solo record. Our discussion centers around the ethos of modern string band music, what the guitar has to say about it, and the potential for folk music’s inherent narrative quality to uplift and move past tradition itself.

Garnett’s perspective on these topics is one that is quite underrepresented: A graduate of the University of North Texas’s famously rigorous jazz guitar program, he spent his early years in Texas developing the skills needed as a pop-oriented sideman and session player, while making ripples in the experimentally disposed Denton, Texas, before heading east. As we’ll find out, he has made disparate musical worlds come together, informing each other along the singular path he leads.

Upon arriving in Nashville, Garnett was quickly recruited as trailblazer Missy Raines’ go-to guitarist, while contributing his compositions and musicianship to progressive acoustic ensemble Circus No. 9. Though his path wasn’t entirely certain at first, his dedicated, open-minded approach to musicianship quickly yielded success both creatively and professionally. Now touring his original music while balancing responsibilities as a band member, the new album Kite’s Keep was made in collaboration with today’s top-of-the-heap acoustic guard: Darol Anger, Chris Eldridge, Brittany Haas, Ethan Jodziewicz, Paul Kowert and experimental pianist-composer Matt Glassmeyer.

I was surprised to hear Ben describe this project as a “guitar” record; being a guitarist myself, and with kindred reference points, I am conditioned to hear six string-born music through the instrument’s highly subjective – yet unendingly capable – lens, though Ben manages to disrupt this. His distinct transcendence of the instrument comes from embracing its format and stepping past folks’ conception of it, while explosively celebrating the guitar as a compositional tool.

Garnett’s ability to write for the room, so to speak, enables him to accommodate many players’ perspectives while balancing high precision with casualness. This is a blend of skill sets and priorities that are rare in ecosystems historically dominated by performative virtuosity. At every turn, Ben Garnett is courteous and grateful, crediting his achievements to friends, linchpins, and heroes within his scene – ones that he now orates his compelling tale alongside.

Is it safe to say that your new record, Kite’s Keep, portrays a narrative? Was that built into your approach as you wrote and recorded it?

Ben Garnett: Absolutely. Poetically speaking, the album title Kite’s Keep loosely refers to this idea of a child’s inner world – a dreamscape where each song represents a different vignette of imagination. The broader narrative has to do with using the acoustic guitar as a world-building tool. This idea that guitar records can be more expansive than just, “here’s my solo arrangement of such and such a tune.”

My goal was to make a record that celebrates the power of what an acoustic guitar can do as an ensemble instrument – like bringing out what other instruments are capable of. The guitar can act as this stage, or world, that other instruments can then inhabit.

So, in that way, would you say that this is a guitar record?

Definitely.

Interesting, because when I listen to it, it doesn’t necessarily feel that way, which is an aspect I’m quite partial to.

I’m curious why this feels like a guitar record to you. I know you’re facilitating these exchanges and you’re world-building with them, you’re obviously pushing past what the guitar is conceived of, but it sounds like you’re not trying to push past the guitar itself.

I guess the idea is that, in addition to world-building, a lot of the compositional material was guitar-born. I’m thinking of the fiddle and bass as extensions of what I would otherwise play. They’re bringing guitar-born ideas into this other register, carrying them to places where the guitar can only point.

Do you have a compositional process? Would you consider it more passive, or do you sit down to compose in a more dutiful way?

Sometimes it’s dutiful, but a lot of the time it’s passive, like when I’m at the airport. Thoughts come to me and I’ll write them down in my notes app. From there, it’s more like script or scene writing. For instance, I’ll want the tunes to arrive at a certain point and I’ll figure out how to get there in reverse. When I’m being more dutiful, I’ll realize a piece in a program like Ableton or Finale, or just by recording myself.

I wrote one tune in a weird way: I improvised freely for 15 minutes, mostly with long tones. The only directive was to play a note and whatever note I heard after that, I would immediately try to play. I chased my tail for 15 minutes and recorded myself. Then I sped up the recording by 400%. I chopped up the transients, warped it, and put the transients on different parts of the metric grid. I had a groove in mind – a half-time, kind of bluegrass-funky tempo. Since it was my melodic sensibility and the way I heard the notes flowing into each other, there was a certain intention and trajectory there.

So, you were kind of sampling yourself – that must get you out of your own head and off the instrument.

Yes. It gave me rhythms and phrasing that I never would have come across otherwise.

And then you learn it from yourself.

Exactly. … It’s the second track, with Darol Anger, “Tell Me About You.”

For something like that, which is more thoroughly composed, how do you make it sound so fluid in the studio while recording?

The process for that tune involved getting the basic elements assembled in Ableton, but then there was the process of arranging the material. Then after arranging, came “breaking in” the tune, so to speak.

Once I had a basic arrangement, I brought it to Darol. We probably got together four or so times. I remember asking him what would make it more idiosyncratic to his instrument and playing. He’d suggest adding a double stop somewhere or doing something rhythmically a little differently. Basically, it was all about massaging it so it didn’t feel clunky. It had to pass all these “tests” before we even got into the studio.

What are these tests that it must pass?

They have to do with the flow. Even if the compositional material comes from using a computer or another unusual place, the music still has to have this casualness. String band music tends to sound its strongest when the parts rely on each other in a certain way. I generally will “test” my music by playing it with as many people as I can, to make sure it has an inherent interpretive quality. Making sure the ideas are robust enough to hold water no matter who’s playing them.

For people who don’t know, you come from Dallas, you went through UNT’s jazz guitar program, and then you moved to Nashville. I’m curious how you found Nashville with your sensibilities, growing of musical age in an environment that is uniquely experimental, yet highly rigorous. Did you come here with the aspirations of doing the things that you’re doing now?

Not at all. At the time, it was much more open-ended than that. I was mostly driven by wanting to get out of Texas. But I had also just gone to the Acoustic Music Seminar with Mike Marshall, Julian Lage, Bryan Sutton, and Aoife O’Donovan, which was a hugely formative experience. I think it was Sutton who offhandedly mentioned, “You should think about moving to Nashville.” I knew there were acoustic musicians here I looked up to – the whole Sam Bush and Jerry Douglas generation of players and I knew Critter [Chris Eldridge] and Sutton were here, too.

At that time, I was also in a phase of wanting to be an electric guitar player. The idea of being a session musician or side-person appealed to me. I had an electric background playing all kinds of music back in Texas – jazz, rock, country, pop, etc. I remember my cousin and my first guitar hero, Andy Timmons, telling me, “Nashville is definitely where I would be if I were your age.” It just seemed like the most open-ended place for the variety of interests I had.

Did you feel like you could do what you wanted to do at first?

It took a while to figure that out. I got a job with bluegrass bassist Missy Raines two weeks after arriving, which was a great first touring experience. I had the idea of making a solo record in my head for a long time, but I always thought I’d wait until I was 30 or so to make it. However, at one point, I distinctly remember Missy telling me, “You definitely need to make a record before you’re 30,” which was amazing advice.

I also got a job with progressive bluegrass band Circus No. 9, a year or so after moving, and was expected to bring in original music to build out our repertoire. The more engrossed I got in the progressive bluegrass world, the more I realized how rare my perspective on it was. It felt isolating at first, but being on the road with Missy and Circus was like being in a second family where I got to realize my position and perspective.

Fast forward a few years, and my hero Chris Eldridge agreed to produce my first solo record, Imitation Fields.

I’m always fascinated by the Dennis Hopper quote where he says one day an actor wakes up and they decide they’re a producer. I’m wondering if you feel similarly in regard to pursuing your voice as a bandleader, composer, artist. I feel like in the current state of the music industry, with how comically hard it is to do anything, it’s almost like a fatalistic, “Why not?”

I’m curious if you could speak to the process of finding yourself in a record of your own stuff and what advice you might give to somebody trying to figure it out.

It goes back to the validation thing. I probably wouldn’t have made a record without all the help and encouragement from those around me. I hate to even frame it this way, but I just have to count my blessings. In some ways, I feel like I walked into something that was waiting for me.

You could have stayed in Texas and made records, but you wouldn’t have made the records you’re making here in town.

Absolutely. Who knows what those Texas records would’ve sounded like.

Going back to your question on what advice I’d give to somebody figuring it out. If you’re an aspiring musician who wants to make your own music, I’d advise not to be too career-oriented at first. Obviously, you need to do what it takes to pay the bills. But there’s a lot of music out there that, to me, sounds born from a certain careerist mentality, which I frankly find to be taking up space.

All the stuff I’m doing now – booking my own tours, stocking merchandise, making promo graphics, being my own publicist (essentially being a small-business owner) – is all really new to me. I moved to Nashville just to see what would happen. I had no real objective. Even if it at times felt meandering or directionless, I’m grateful for the space I inadvertently gave myself to try things. You find yourself in that process, and I think your art becomes more meaningful as a result.

Another factor worth considering in finding myself was the impact of COVID. Critter and I were in the middle of editing Imitation Fields during this time and I think if it weren’t for COVID, it could have easily been, “Okay, we’ve recorded now – let’s edit, mix, master, then done.” All the sudden, it became a whole process of, “What if we tried this? What if we did that?”

It’s like being in a block of molasses. You’re not thinking, “I have three days in the studio, and we have to figure it out.”

Exactly. We had all this time. No corners were cut. … It was kind of insane. I didn’t quite realize it at the time. I’m just really grateful, even if it ultimately drove me a little crazy.

As someone who puts a lot of meticulous work into the visuals which accompany your music, how do you feel that film informs music and vice versa?

First and foremost, the two seem inseparable. For those of us who can see and hear, we’re always looking at something while we’re listening and we’re always listening while we’re looking. That connection is inherent, so my argument is, why not have a say in both realms of sensory experience?

On top of that, I think there’s something cinematically interesting with the traditions of jazz and folk music. A lot of folk music tends to have this quality of wanting to tell a story, albeit in a fairly literal way. Listening to a song, there can be this mini-movie playing in the listener’s mind. Maybe they’re imagining a character, or their own life experiences – whatever the case may be, it largely seems to be about evoking imagery on some level.

In contrast, that kind of storytelling seems less of an objective in jazz. Jazz tends to revolve around this more abstract, spontaneous kind of communication. Which feels equally as cinematic, but the goal of that storytelling feels distinctly different than with folk music.

Of course these are generalizations and I don’t mean to be reductive with either music. This is all to say – the way these traditions interact with our “cinematic” experience of music is something I find deeply fascinating and is a huge source of inspiration for my writing and playing.

It’s the same phenomenon with a song like “Nine Pound Hammer” that has lyrics and semantic content, but is also a vehicle for instrumental virtuosity. I feel like you’re meeting in the middle there.

Absolutely. This is where bluegrass, in some ways, has the best of both worlds.

What I think initially drew me to folk music, in general, was the cinematic quality I didn’t get playing jazz standards. Obviously, there’s the storytelling you get listening to the great singer-songwriters, but there’s also listening to bands like Strength in Numbers. It feels like cinematic stories are being told in those compositions.

Do you feel like a more approachable rhythmic foundation provides a shoo-in for listeners to more quickly imagine a world?

It certainly can. But I also think it’s this general narrative quality in folk music that provides this. For instance, when I play a tune with Brittany [Haas], there’s almost this unspoken objective between us to build the tune in a certain way. In a way that’s very different from playing a jazz tune.

As an aside, I think that’s why people sometimes misunderstand jazz or say they can’t connect with it. Most of the time, jazz isn’t trying to do what most pop or folk music is doing. It’s not trying to conjure a story in this literal way. What makes jazz work is how it centers around this more abstract, colloquial communication.

Perhaps in that way, music school’s training isn’t always “backwards compatible.” Is that fair to say?

I grew up being taught a certain set of rules about how to make good music from going to jazz school. Then, when I moved to Nashville and started working with string band musicians, I realized what I was working with was quite different from the rules they had grown up with.

I think this intersection is what makes someone like Edgar Meyer a powerful force. In some ways, he’s able to pull out all these things in people like Jerry Douglas, Russ Barenberg, Béla Fleck, Mike Marshall, and Sam Bush by bringing in this other perspective from his classical background.

He also realized that the same rules did not apply.

Exactly. He’s able to take what those musicians are giving him, see what they’re good at, harness it, and arrive at a perspective that none of them would have had otherwise.

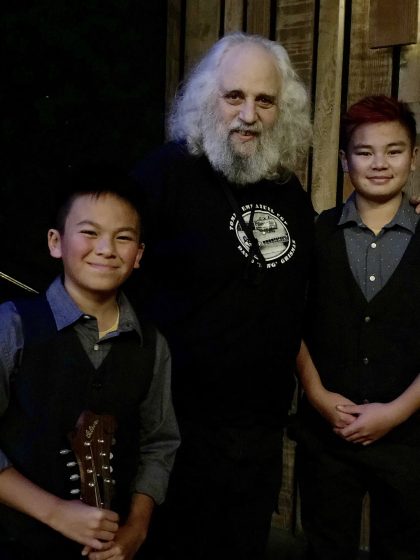

Photo Credit: Natia Cinco