To celebrate Black History Month – and the vital contributions of Black, Afro-, and African American artists and musicians to American roots music – BGS, Good Country, and our friends at Real Roots Radio in southwestern Ohio have partnered once again. This time, we’ll be bringing you weekly collections of a variety of Black roots musicians who have been featured on Real Roots Radio’s airwaves. You can listen to Real Roots Radio online 24/7 or via their FREE app for smartphones or tablets. If you’re based in Ohio, tune in via 100.3 (Xenia, Dayton, Springfield), 106.7 (Wilmington), or 105.5 (Eaton).

American roots music – in any of its many forms – wouldn’t exist today without the culture, stories, skills, and experiences of Black folks. Each week throughout February, we’ll spotlight this simple yet profound fact by diving into the catalogs and careers of some of the most important figures in our genres. For week two of the series, RRR host Daniel Mullins shares songs and stories of Stoney Edwards, Rissi Palmer, Keb’ Mo’, Tina Turner, and DeFord Bailey. Check out the first week of the series here.

We’ll return each Friday through the end of the month to bring you even more music celebrating Black History and the songs and sounds we all hold dear. Plus, you can find a full playlist with more than 100 songs below from dozens and dozens of seminal artists, performers, songwriters, and instrumentalists from every corner of folk, country, bluegrass, old-time, blues, and beyond.

Black history is American roots music history; the two are inseparable. As we celebrate Black History Month and its legacy, we hope you’ll join us in holding up and appreciating the artists who make country, bluegrass, blues, folk, and Americana the incredible and impactful genres that they are today.

Stoney Edwards (1929 – 1997)

If you don’t know the late, great Stoney Edwards’ name, it’s time to fix that – because his story in country is as powerful as the songs he sang.

Born Frenchie Edwards in Seminole Country, Oklahoma, in 1929, Stoney was part African American, Native American, and Irish. The son of sharecroppers, he was a prominent bootlegger in Oklahoma during his younger years. Stoney had dreams of playing the historic Grand Ole Opry. His big break in music would come later in life, in his early 40s, when he was discovered in California singing his honky-tonk style at a benefit for the King of Western Swing, Bob Wills.

Stoney was signed to Capitol Records in the early ’70s and from there he made history. He scored fifteen charting singles, including a pair of Top 20 hits, one of which – his 1973 hit “She’s My Rock” – is still revered as a bona fide country standard later covered by artists like Brenda Lee and George Jones. His songs were deeply authentic, whether he was singing about love, loss, or his own experiences growing up poor and Black in America. He gave a voice to the underdog, often drawing from his own struggles, including battling discrimination and working blue-collar jobs before music. Edwards would also record several songs saluting his country heroes over the years, including “The Jimmie Rodgers Blues,” “Daddy Bluegrass,” and his Top 40 hit, “Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul.”

Stoney’s music wasn’t just about catchy melodies; it was about storytelling. His debut single was inspired by a true story. Before he hit it big as a country singer, Stoney was trying to provide for his family working as a forklift operator at a steel refinery in San Francisco. A workplace accident resulted in Edwards being sealed up in a tank and suffering dangerous carbon dioxide poisoning; he endured an extensive two-year recovery, both physically and mentally. During this time, Stoney was struggling to care for his wife and children, so he planned to leave in the middle of the night. However he tripped over one of his daughter’s toys, and it prompted him to stay. In 1970, backed by the virtually unknown Asleep at the Wheel, Stoney Edwards released his debut single, the autobiographical “A Two Dollar Toy.”

While his career didn’t reach the same commercial heights as some of his peers, Stoney Edwards left an indelible mark on country music. He paved the way for greater diversity in the genre and showed that country music is for everyone – no matter where you come from or what you look like. Stoney Edwards passed away from stomach cancer in 1997 at the age of 67.

Suggested Listening:

“She’s My Rock”

“Hank and Lefty Raised My Country Soul”

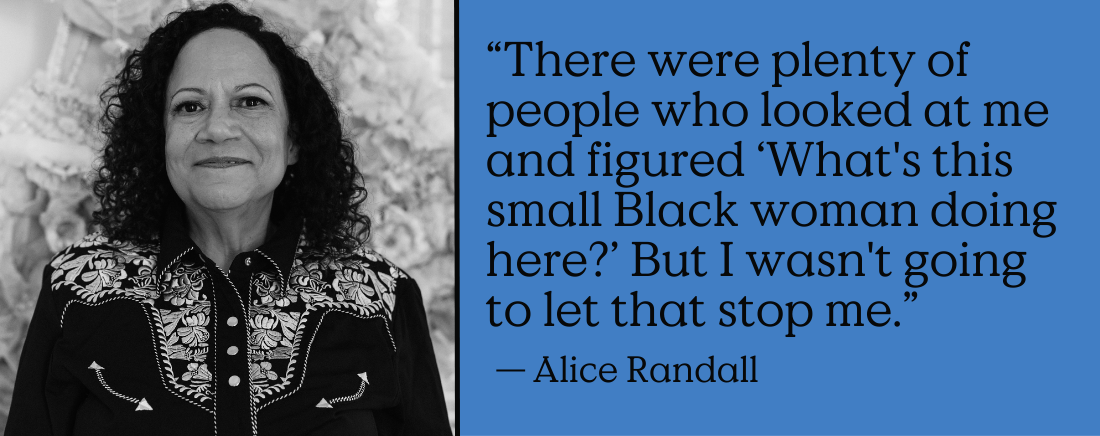

Rissi Palmer (b. 1981)

She’s a trailblazer in country music, a voice for change, and an artist who refuses to be boxed in – meet Rissi Palmer!

Palmer’s mother passed away when she was just seven years old, but she instilled in her a love for the music of Patsy Cline. Rissi would burst onto the country scene in 2007 with her hit single, “Country Girl,” making history as one of the few Black women to chart on the Billboard country charts. Rissi has built a career on breaking barriers by blending country, soul, and R&B into a sound all her own. She has penned some empowering original songs, helping folks on the margins feel seen, especially her most personal song, “You Were Here,” dealing with the heartbreak of a miscarriage.

Beyond the music, Palmer uses her platform to uplift underrepresented voices in country and roots music. As the host of Color Me Country radio on Apple Music, she spotlights Black, Indigenous, and Latino artists in country music – proving that the genre belongs to everyone. With her powerful voice and unwavering spirit, Rissi Palmer isn’t just making music, she’s making history.

Suggested Listening:

“Leavin’ On Your Mind”

“Seeds”

Keb’ Mo’ (b. 1951)

Keb’ Mo’ is a modern blues legend. Born Kevin Moore, this L.A. native blends Delta blues with folk, soul, and a touch of country. With his smooth vocals and masterful guitar skills, he’s kept the blues alive for over four decades.

Mo’ is heavily influenced by the late Robert Johnson, who preceded Keb’ by about 60 years. Keb’ portrayed Robert Johnson in a 1998 documentary and included two Johnson covers on his breakthrough self-titled album in 1994. He has since won five GRAMMY Awards, collaborated with legends like Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, and Taj Mahal, and performed for multiple U.S. presidents.

Mo’ is embedded in country and Americana music as well, working with cats like Lyle Lovett, Old Crow Medicine Show, John Berry, Alison Brown, Jerry Douglas, and Darius Rucker over the years. He has been quick to share his respect for country and gospel traditions, appearing on the critically acclaimed all-star album, Orthophonic Joy, recreating the magic of the 1927 Bristol Sessions – country music’s big bang.

Whether he’s playing a heartfelt ballad or a foot-stomping blues groove, Keb’ Mo’ keeps the genre fresh and timeless. His music isn’t just about the past – it’s about where the blues is going next. We love his passion for all things American roots music. Fifty years into his remarkable career, Keb’ Mo’ is still one cool cat.

Suggested Listening:

“To The Work”

“Good Strong Woman” featuring Darius Rucker

Tina Turner (1939 – 2023)

She was the Queen of rock ‘n’ roll, but did you know Tina Turner had deep country roots?

Born Anna Mae Bullock, she grew up in Nutbush, Tennessee. Tina recalled picking cotton as a youngster during her hardscrabble rural upbringing. Her musical journey began by singing at church on Sunday mornings. She grew up on country, gospel, and blues. Turner and her husband, Ike (who was abusive towards her) had massive success in R&B and rock and roll, but her first solo record was actually a country album.

In 1974, Turner released her debut LP, Tina Turns The Country On!, introducing herself as a solo act. Featuring top musicians, including Country Music Hall of Famer James Burton on guitar, Tina tackled songs from country greats like Dolly Parton, Kris Kristofferson, and Hank Snow. It would go on to receive a GRAMMY nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance in 1975. Over the years, unreleased songs from this groundbreaking album would be dropped, including her powerful take on “Stand by Your Man.”

However, her most enduring impact on country might be as the inspiration behind one of the outlaw movement’s most popular hits. In 1969, Waylon Jennings was staying at a motel in Fort Worth, Texas, when he saw a newspaper ad about Ike & Tina Turner that intrigued him enough to interrupt Willie Nelson during a poker game so they could write a country classic. The phrase that struck Waylon heralded Turner as “a good hearted woman loving a two-timin’ man.” Sound familiar?

From honky-tonks to stadiums, Tina Turner’s fiery spirit left an unforgettable mark on practically every genre – country, rock, and everything in between.

Suggested Listening:

“Stand By Your Man”

“Good Hearted Woman”

DeFord Bailey (1899 – 1982)

Let’s go back to the early days of country to a name that shaped the Grand Ole Opry, but is often forgotten: DeFord Bailey, “The Harmonica Wizard!”

Born in 1899 in Smith County, Tennessee, Bailey grew up around banjos and fiddles in a musical family, saying that he learned the “Black hillbilly music” tradition. He overcame polio as a child, resulting in his short stature – he was only 4’ 10” tall – but it was through this ordeal that he found his voice in a harmonica. While recovering from the disease, he was bedridden for a year, and learned to mimic the sounds he heard outside on his harmonica: trains, animals, and the rhythms of life.

In 1927, Bailey became one of the first stars of the Grand Ole Opry on Nashville’s WSM, dazzling crowds with hits like “Pan American Blues.” He was actually the first artist introduced after George D. Hay referred to WSM’s Barn Dance as the “Grand Ole Opry” for the first time to poke fun at NBC’s classical Grand Opera. Bailey would also become the first artist to record in Music City. His hits like “Fox Chase,” “John Henry,” and “Evening Prayer Blues” captivated radio audiences, making him one of the Opry’s most popular performers. He would tour with other stars like Roy Acuff, Uncle Dave Macon, The Delmore Brothers, and Bill Monroe, but would often not be allowed to stay in the same hotels or eat at the same restaurants as his white contemporaries due to Jim Crow laws.

In 1941, DeFord Bailey was unceremoniously fired from the Grand Ole Opry under suspicious circumstances. He would make his living shining shoes in Nashville and would not perform on the Opry again until 1974, the first of only a handful of final performances on the radio program which he helped grow during its infancy, before his passing in 1982.

The Grand Ole Opry would eventually work to reconcile its mistreatment of its first Black member, issuing a public apology to the late DeFord Bailey in 2023 with his descendants on hand. Old Crow Medicine Show was there to celebrate the occasion, performing their tribute song to Bailey led by black percussionist Jerry Pentecost, entitled “DeFord Rides Again.”

In 2005, Bailey was rightfully inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame and over 40 years since his passing, he is still recognized as the Harmonica Wizard.

Suggested Listening:

“Pan American Blues”

“Evening Prayer Blues”

Want more Good Country? Sign up on Substack for our monthly email newsletter full of everything country.

Listen to Real Roots Radio online 24/7 or via their FREE app for smartphones or tablets.

Photo Credit: Stoney Edwards by Universal Music Group; DeFord Bailey courtesy of the Country Music Hall of Fame; Rissi Palmer by Chris Charles.