It is clear to me that 2024 will be known for being a landmark year in the evolution of Black roots music. Not only has there been tremendous growth in the number of artists that are throwing their hat in the ring for roots music – whether it be country & western, bluegrass, folk or Americana – but it is also a time where the mainstream music world is responding to this outpouring of talent in a way that hasn’t been seen in a long time. In many ways, it’s not surprising that things have grown in this fashion. Since I started my professional music career back in 2005, I have seen quite a few changes in the general musical landscape that have set the stage for a Black Roots music revolution.

In the early 2000s, the musical fabric of Black Roots had already been woven into the tapestry of American culture. Hidden between the more well-known pieces of Black music, these acoustic styles that didn’t fit into the traditional mold of blues, jazz, and gospel remained unseen and unheard, relegated to the fringes. Even though it was simultaneously considered a quintessential piece of the larger puzzle of American popular culture, Black Roots music was held in greater reverence for its historical significance than for being a living musical tradition played by modern musicians of the African Diaspora.

There were great pioneers who set the stage back in the early 20th century. There were songsters, string bands, folk musicians, storytellers, songwriters, composers, and community historians who shared their stories for the early folk song collectors who were searching for the purest forms of black expression. This happened while the commercial recording companies sent their representatives out to the field looking for music that they could sell to a record buying public who wanted a sound that not only reflected the past, but the future as well.

With all that in mind, my goal in becoming a professional musician came not from a desire to be a stage performer alone, but to also expand the scholarship and visibility of Black Roots music. By becoming a touring musician I found I was filling a void that most people are not aware of today. Having the opportunity to evoke the names of people who had not gotten their due in their own time was empowering. Not only have I advocated for the music, I have played it and arranged it to reflect the rich history of American music while at same time writing my own songs that represent the modern Black experience in all of its phases.

When I first began performing in Arizona, there was no Black Roots community for me to lean on, so I had to teach myself everything. I had to learn to play the guitar, the banjo, and all of the other instruments in my repertoire on my own. Before the internet, the library was my main resource for music and I grew up in a time when a good portion of all of the world’s recorded music throughout history was not readily available on streaming platforms. Sometimes, I had to search far and wide through stacks of CDs, LPs, and 78s to gain access to the music, just so I could learn how to play it. As I began to learn more songs, I found out about the history of the performers and the legacies they left behind. Later on, I met others who held a similar passion and those individuals taught me how to play different styles and shared more parts of the history that I didn’t know about.

We are now in an era where people have access to the music that was once very hard for me to find. In many ways, I was at the forefront of these musical discoveries in the roots music community, because I took what I had learned and planted seeds all around the world with the Carolina Chocolate Drops and on my own as a solo artist over the past 25 years.

Once I left Arizona and we formed the Carolina Chocolate Drops, we were able to tap into a certain energy in the crowd that changed the paradigm for Black Roots music, so that now people can see the whole picture of American music in a different way. They could see a Black person playing the banjo in the modern world and be inspired to learn more about the African and Caribbean roots of the banjo. We did that for the better part of a decade and then I decided to move on into a new territory: Black Cowboys and Black Western music. This was a new area of music that the Carolina Chocolate Drops were not a part of in any way. The Chocolate Drops had focused on the music of North Carolina and this new musical venture was an exploration into my own family roots in the Southwest.

Back in 2010, I had come across a book called The Negro Cowboys, which encouraged me to research about African American cowboys of the West. In 2018, my research came together in my solo album, Dom Flemons Presents Black Cowboys, which came out on Smithsonian Folkways as a part of the African American Legacy Series. Having grown up in Arizona, I knew that the album needed to be a part of the National Museum of African American History & Culture so that future generations could appreciate and respect the history of the Black West as well as activate the communities that had been there all along.

Back when I released Black Cowboys, I was one of the few artists talking about the contributions of African Americans out west and their varied connections to country music. Not only was I sharing this lesser known history, but I was playing the music that we now celebrate as “Black Country” long before Beyoncé, Lil Nas X, the “Yee-Haw Agenda,” or any of the newer Black artists who have risen to fame in the TikTok era. Now that the concept of Black Cowboys has gone mainstream in music, television, movies, and fashion, it’s another reminder to me that the music I created had made a major impact on American culture in both a conscious and subconscious way.

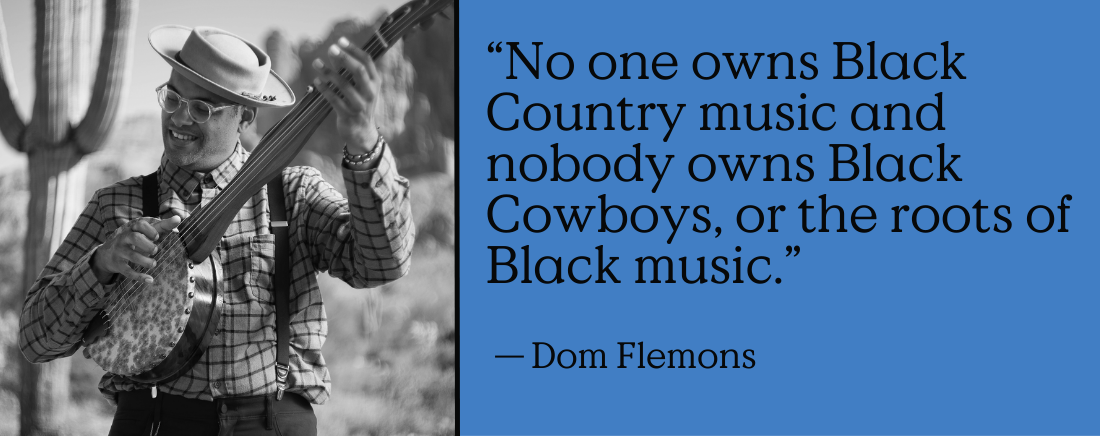

The most important part of it all is that no one owns Black Country music and nobody owns Black Cowboys or the roots of Black music. However, nowadays I am noticing that people are trying to take credit for exposing the history when they have only scratched the surface of it.

What I have learned is that there are so many parts of the Black Country and roots music story that are still missing and are being left out of the media. There are many other artists who should be considered in the conversation and yet they aren’t getting their flowers. I have noticed the Black Country music narrative that has sprung up recently has actively disregarded the work of the many Black artists who are deeply connected to the legacy, including myself on many occasions. My hope is that people will take the time to acknowledge the ones who have paved the way for the current movement and shed light on their individual stories, too.

The main reason I have included extensive liner notes in all of my albums, including my most recent, Traveling Wildfire, is because I always make sure to give credit where it is due. The sources for my traditional songs are clearly laid out for anyone to see and my original songs are exercises in expanding the existing palette of roots music so that both can be presented to a new generation of listeners. I have seen my talking points being used to fuel many of the current conversations, but oftentimes there is no back reference to the work I have done. All of the fanfare has forgotten to give proper credit to someone who has spent the majority of their career trying to set the record straight. As a well known musician in my community, this exposes a general trend that is problematic for the current state of Black Roots music.

If it is acceptable for a mainstream pop star or the media to sidestep and steamroll the pioneers of Black Roots music, it can only lead to a narrative of uplift that will ring hollow in the long term. It will teach the future generations that sleight of hand is the only way to get ahead and that surface level fame is the goal and key to being successful. Bad ideologies take a long time to disperse once they have become a part of the general fabric of society, and if people continue to spout it the integrity of the music can be undermined without them even knowing it.

This is why I am cautiously optimistic for the current state of Black Roots music, because oftentimes it feels more like a one-sided competition than a community of Black artists coming together to be celebrated collectively.

Yet, on a positive note, I believe the current state of Black Roots music is very exciting. People are being activated by the work that has been done by the pioneers of the past one hundred years. They are reinterpreting, reinventing, and showcasing music that is becoming a viable part of the mainstream music industry. They come with a variety of sounds, instruments, and songs that will shift the template of American culture as Black Roots music always has and always will.

More voices are being added every day in places and spaces that would have been unheard of even ten years ago. It can be clearly stated that there are now plenty of young musicians in every field of Black Roots music and there is no shortage of new talent who have proven their worth on the stage, on recordings, and on social media.

The holistic landscape of the modern Black Roots music community is something that I am proud to have helped establish over the past 25 years. Major growth is upon us, but I feel like it can only happen if everyone in the community gets acknowledged, not just the “favorites” or the ones making the most money while begging for all of the attention. The connecting of dots that bind the past and future are within our reach through the technology we have at our fingertips; it is essential for us to use it with great care and responsibility.

I started my journey as the American Songster building a legacy upon a dream. I got the notion to write songs and play the old styles back when I was sixteen years old and this eventually led me to sell everything I own, jump in my car, and drive across America to find where that dream could take me. It then took me all over the world and brought me much acclaim, but I have never lost sight of what inspired me to start this journey.

For me, I’m just getting started and I’ll always be here, no matter who stays and who goes. I’ve done the work to make the music more accessible for others and I can hope that it has reflected well on my own legacy as well as the entire community I have tried to uplift.

Photo Credit: Dom Flemons by Steven Holloway.