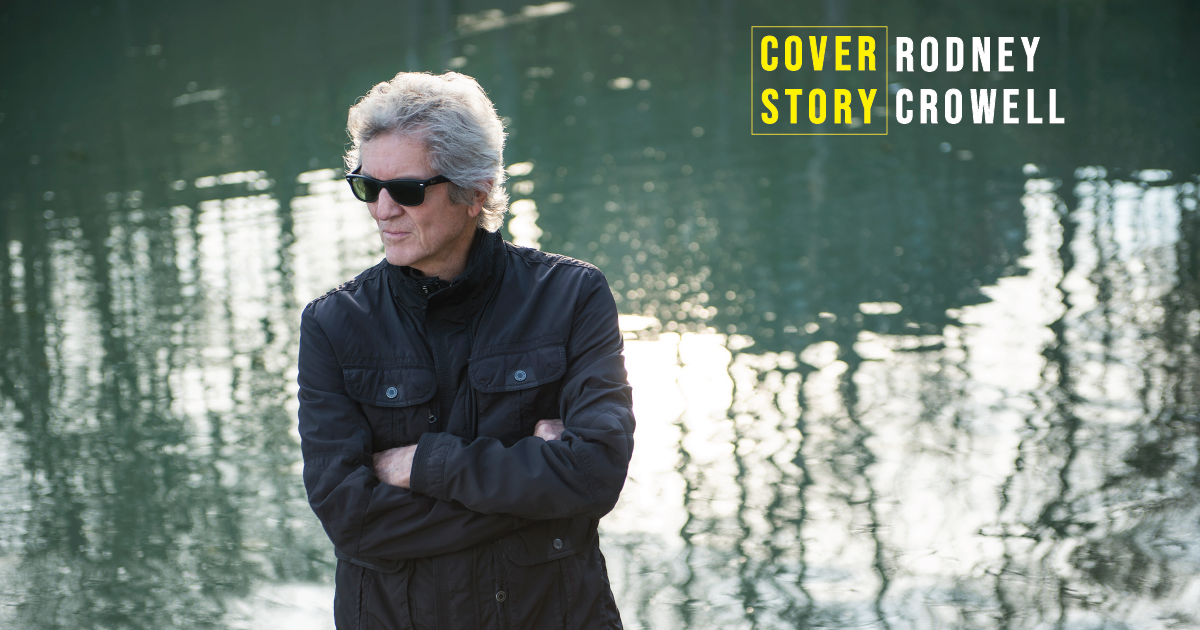

Heartbreak songs, political takedowns, pronunciations of judgment — on his 18th album, Triage, Rodney Crowell doesn’t indulge much in any of them, with the possible exception of judging his own foibles as he burrows deep into his psyche, hoping to extract whatever nuggets of wisdom might still be buried there.

To help in the trenches, he enlisted son-in-law Dan Knobler, a rising talent who produced one of Crowell’s current favorite albums: Allison Russell’s Outside Child. “I respect him, and I learn from him,” Crowell says. “I learn from young people around me. You kiddin’? They’re on to things that I’m not on to, and they have information that I need.”

Knobler’s not the only family tie: another young artist, Jakob Leventhal, sings backing vocals on “Hymn #43,” a track that also contains contributions from his parents, John Leventhal and Rosanne Cash — Crowell’s ex-wife and mother of Knobler’s wife, Carrie. And though it’s “aimed more at the universal than the personal,” there is an homage to Joe Henry, who produced three Crowell albums: Sex & Gasoline, Kin: Songs by Mary Karr & Rodney Crowell, and The Traveling Kind, his second collection of duets with Emmylou Harris.

“I have a deep abiding love for Joe,” Crowell says. “I wrote the song ‘Triage’ for and to Joe, because the conversations we had when he was in the darkest part of coming to grips with a pretty shocking [cancer] diagnosis, his vulnerability and his courage and willingness to embrace everything about it inspired me, and I wanted to make a song based on the inspiration that I got from Joe’s courage and truthfulness.”

Courage and truthfulness. Those qualities permeate the entire album; in fact, it’s safe to say they’ve guided Crowell’s entire career.

BGS: Reviews are saying Triage is one of your most personal albums, and you referred to making amends in an NPR interview. But I suspect your use of “triage” has more to do with the global state of affairs than the need to address any personal sort of emergency at this stage of your life. Is that a reasonable assumption?

Crowell: Yeah, that’s most reasonable. I think the conversation with NPR started with the opening song [“Don’t Leave Me Now”], which is basically an attempt at amends, and it went from there. But the broader stroke on the album, and in my contemplation as I was writing the song, was how do I weigh in without dating myself? If you go political, or if you go topical in the moment, six months from now … you know, unless you write “Blowin’ in the Wind” or “This Land is Your Land,” you’re not timeless.

So my overview is that I want to write about, say, climate change, and I want to write about a monotheistic approach to livin’ my life, and instead of writing about boy/girl love, to write about a higher love — as Steve Winwood sang, “Bring me a higher love.” That’s what I had in mind, so I spent a lot of time revising all of the songs, checking and double-checking to make sure that I was grounding the language, because I was reaching into that place that’s very hard to define.

And yet, you do go topical on “It’s All About Love,” referring to Greta Thunberg and others, in that kind of talking-blues list style that you do so well. You often throw in pop-cultural references; how do you choose what works?

Well, when COVID happened, I got to slow down a bit and not try to race to make a release date, which allowed me to go back through the songs … you know the old saying, “Show, don’t tell”? I was able to go back through and say, “Oh, here I’m telling. I need to bounce this out of here,” and to stay in the show part of it, which is whatever metaphorical angle you take or however you ground the language in such a way that you can’t be accused of thinking you know better than everybody else.

It’s tongue in cheek for me to stick Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin and Greta Thunberg and Jessica Biel and the devil all in one stanza; honestly, I’m giggling to myself. They might not get it; they may take me literally, but this is humor.

You touch on religion repeatedly, and at one point in “I’m All About Love,” you chant the names of the lord, so to speak, so the sense is acceptance. Yet you mentioned monotheistic love, and the notion that there is one particular God seems to be expressed here, regardless of which one.

My mother was quite religious in the Pentecostal, speaking-in-tongues, emotional religious paradigm, and even as a child, it didn’t serve me. I just sensed something was amiss with it. I’ve always felt that way. Religion, I mistrust; the creator of it all, I do trust. Whether that creator of it all is a team, or whatever that is, I don’t really know. But I feel it. And hopefully, as I’m writing the songs and exploring that, I’m not saying that I really know, because I don’t. I can’t tell you anything about your god, and I really can’t tell you a lot about mine. But I sure do have a feeling.

When you’re writing songs, in some cases, you must have specific people or incidents in mind. But you also want to get them to the point where they have that universal feeling, where the listener can relate it to something in their own life. How do you strike that balance of not revealing too much about what’s going on in your life, while alluding to enough of it that it does personalize the lyric and make it touching?

I learned a long time ago, if it’s coming from my own experience, there’s a good chance I’m a step closer to true. And I can mine my personal truth, but confessional only goes so far. I’ve tried to walk that line; if I can carefully write about my own experience and put it in a broader perspective, then [for] the listener, it becomes their experience. It’s no longer my experience. That’s why I feel like I have to be really careful; if I make it too much about my experience, then I start to tread on the listener’s experience. The goal is to get it in such a way where — and there again, it’s the “show, don’t tell” — if it’s show, you show somebody their emotion, their experience. If you tell, you’re tellin’ ’em about you. And down there somewhere in the gravel of it all, I’m telling you about me.

But you’re actually not revealing that much, even though it comes across that way. I can’t listen to this and guess what’s happening in your life, even though I can sense what has happened, possibly.

Well, there you go. If that’s your experience, then I’ve succeeded, because I don’t want [the song] to be about me. I want it to be about it.

Other songs here, like “One Little Bird” and “Girl on the Street,” seem to be written for your children, or specific children. Am I close?

Yeah, you are, in a way. “Girl on the Street,” it’s something that happened in San Francisco. I met a girl and … however she could get money off me for drugs, she was willing to go there. And she was young and beautiful and reminded me of my own children. That was why the regret that the narrator has in the song is like, “I could have done more.” I could have bought her a room for the night where she could get a shower and a good night’s sleep. Or I could have taken her and bought her something to eat and sent her on her way, but no; I gave her 45 cents. So I really failed as an adult on the street. And that’s what I hope the song says.

Regarding amends, who in your life do you feel you haven’t apologized to that you still need to?

I’ve apologized to everybody that needs to be apologized to. But that doesn’t mean everybody accepted. And I have to live with that. If you look closely, in “One Little Bird,” it’s in there. I’ve been rebuffed.

You hit that one high note in “One Little Bird,” that falsetto, that I don’t think I’ve heard you do before. It’s evident that there’s definitely some change in your vocal style; that it’s actually expanding with age, which is interesting, because one would not expect that. Are you doing more training, or just finding ways to do that yourself?

I’m learning; as a matter of fact, I retired “Shame on the Moon” from my performances for years because Bob Seger sang it so damned well. And I’ve reinstated it into my live shows for the first time since ’84. I got an outro that will stand alongside Bob Seger’s now, as far as I’m concerned. I can ad-lib the outros in a way where I feel like, “OK, this is my song again.”

You took possession back.

Yes. I’ve repossessed “Shame on the Moon.” [Laughs] But I had to grow as a vocalist to where I could legitimately reclaim it. So that’s cool, I mean, from my perspective, to want to grow to become better. If I know that I’m getting better on that front, I’ll keep on writing songs because I’ll want to continue to experiment with what I can do.

I wanted to address the issue of mortality a bit. Let’s face it, we’re not all that young anymore, but it sounds as if you’ve still got a lot of plans. So how do you regard life now that there’s plenty of it in the rearview mirror, but you’re not ready to sign off?

Now that time is compressed? [Laughs]

Yes.

As a younger artist, quote/unquote, I was quite comfortable with broad-stroke; I wrote “Please Remember Me” and “Making Memories of Us” and those broad-stroke love songs because I was experiencing life in a way that I was trying to express myself outward, to understand how I fit into that world out there. And now as I age and become a septuagenarian, I made Triage as the kind of record it is because I am facing mortality. As you realize that the time out in front of you is a lot shorter than the time behind you, rather than going for those broad-stroke love songs to send out there into the world to find out who you are, I’m writing about my interior life, because I think, to prepare myself to leave this planet, I have to have a better understanding of my interior self.

What would you still like to achieve that you haven’t yet?

Mmmm, that’s interesting. Well, I’m working on achieving certain things as a singer that continue to reveal themselves to me. I’ve become a better singer and I’m continuing to develop as a vocalist. That makes me happy, because for a long time, I was very unhappy on that front. As I age, the more singular my sensibility becomes about my interior experience; I’m also arrogant enough to think that’s worth sharing out there with these records that I make. But I may yet open up onto another plateau where I’ve examined mortality enough that, hey, it’s time to celebrate a little bit, and I’m gonna make a blues record, or I want to make a honky-tonk record that sounds like 1954. Who knows? I’m pretty much free to do exactly what I want to do.

Photo credit: Sam Esty Rayner Photography