It’s a serendipitously Canada-filled day on You Gotta Hear This, where singer-songwriter Rose Cousins brings us a brand new track, “Forget Me Not,” with a beautiful accompanying visualizer, plus Alex Mason impressively performs “Broken Bottles” live from a canoe, and Bob Sumner and posse line-dance it up in a new video for “Motel Room.”

That’s not all, though, as we’ve got alt-country, bluegrass, and more from the southern side of that border, too. Don’t miss Reckless Kelly performing “Keep Lookin’ Down The Road” in a brand new, self-shot video that features gorgeous landscapes and stunning drone footage. Derek Vanderhorst brings us the title track to his upcoming album, Be Kind, as well, with a ringer cast of collaborators including Steve Poltz.

To round out our collection this week, we’re re-sharing two premieres from earlier in the week on the site. The Doohickeys brought us zombie-fied Good Country with “Rein It In Cowboy” and virtuosic pickers Steven Moore and Jed Clark paid tribute to what would have been Frank Wakefield’s 90th birthday with their rendition of “New Camptown Races.”

It’s all right here on BGS and, to be perfectly honest, You Gotta Hear This!

Rose Cousins, “Forget Me Not”

Artist: Rose Cousins

Hometown: Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Song: “Forget Me Not”

Release Date: June 28, 2024 (single)

Label: Nettwerk Music Group

In Their Words: “‘Forget Me Not’ is the romance of spring unfolding into summer as it pulls us into its presence. Nature asking us to pay attention and come along. Spring is my favourite season and I’ve now gotten to see it four times in a row in the same place which touring kept me from doing for years. It’s been like falling in love in a new way with an old flame.” – Rose Cousins

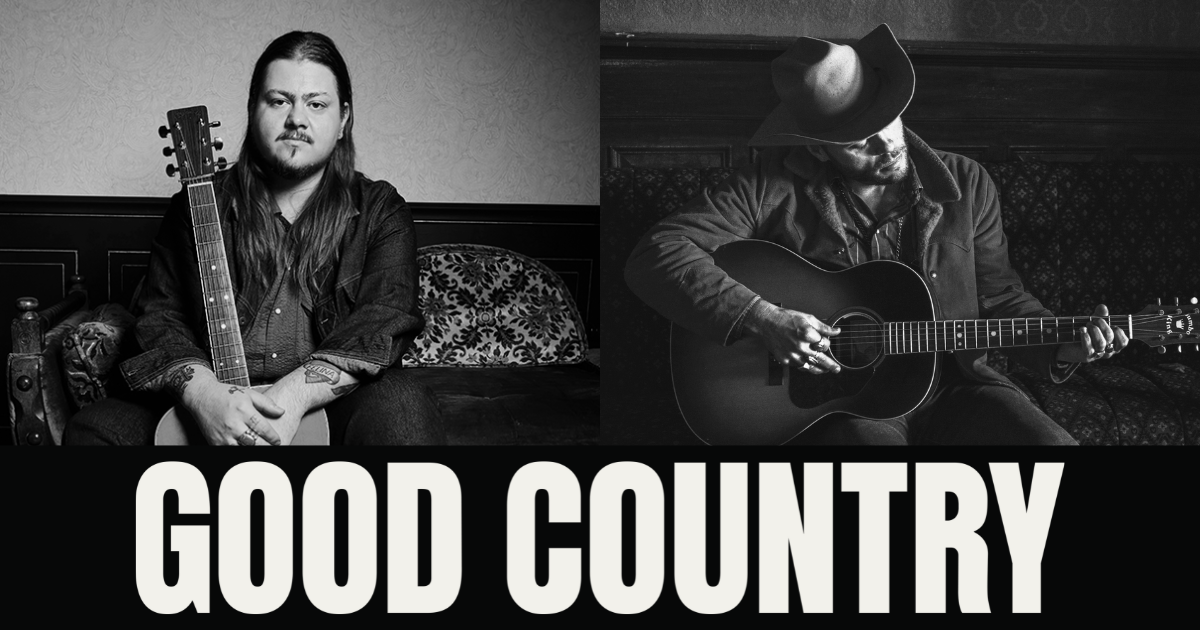

Reckless Kelly, “Keep Lookin’ Down The Road”

Artist: Reckless Kelly

Hometown: Austin, Texas

Song: “Keep Lookin’ Down The Road”

Album: The Last Frontier

Release Date: September 13, 2024 (album)

Label: No Big Deal Records

In Their Words: “‘Keep Lookin’ Down The Road’ is a reflection of the past and an appreciation for the present, but most importantly, it’s an optimistic look ahead. I wrote it with my brother Gary and our buddy Jeff Crosby during our annual songwriting retreat that we jokingly refer to as the ‘hitscation.’ I came up with the line on the way there. sang a few lines into my voice recorder, and we worked out the rest over the next couple of days. Once we were in the studio, I chopped up a couple of verses and used the best lines to shorten it up a bit to match the theme of the record, which is, in a nutshell, ‘Don’t bore us, get to the chorus.’

“As technology advances by the second, I’ve wondered for a while how close to a pro-shot music video I could film using just an iPhone and a drone. Since the expense of filming a music video can sometimes outweigh its visibility, I decided to find out. Using the limited videography and editing skills I’d picked up filming the pandemic-inspired ‘Music from the Mountains’ and ‘Quarantine Kitchen’ shows, I set up time lapses of sunsets, sent the drone up to capture areal views of the mountains in my high desert backyard, and tried to time sunrises and sunsets for the cringiest part – standing in a field of sagebrush all alone, Uncle Rico style, filming myself singing and playing the song in front of a tripod. Luckily, my locations were so remote that nobody drove by and saw this old man making selfie videos like some 14-year-old influencer.

“I shot a lot of B roll road scenes, filmed at an old junkyard in the woods, waterfalls, national monuments, and in huge valleys surrounded by mountains on all sides. I tried to use the scenery as the main focus and also borrowed my brother Gary’s old Dodge truck to match the timeless vibe I was going for. It was a lot of work and took a lot more time than I thought it would, but it was fun and it turned out pretty cool, and I have a newfound appreciation for why these things cost so much. I’m not sure if I matched the quality of a high-end production, but for the cost of a tank of gas or two it’s close enough for RK!” – Willy Braun

Track Credits: Written by Willy Braun, Gary Braun (Micky & The Motorcars) and Jeff Crosby.

Wily Braun – Lead vocals, rhythm guitar, harmonica, percussion

Cody Braun – Fiddle, harmony vocals, mandolin, tenor guitar, synth, percussion

Jay Nazz – Drums, percussion

Joe Miller – Bass guitar

Geoff Queen – Lead electric guitar, pedal steel guitar

Bukka Allen – Hammond B3 organ, piano, harmonium

Kelley Mickwee – Harmony vocals

Produced by Jonathan Tyler, Cody Braun, Willy Braun.

Engineered by Joseph Holguin.

Mixed by Jacob Sciba, Cody Braun, Jonathan Tyler.

Mastered by Jacob Sciba.

Recorded at Arlyn Studios, Austin, Texas.

Additional recording at Clyde’s VIP Room, Austin, Texas.

Video Credit: Produced, directed, filmed, and edited by Willy Braun. Filmed on location in Idaho.

Alex Mason, “Broken Bottles”

Artist: Alex Mason

Hometown: Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Song: “Broken Bottles”

In Their Words: “‘Broken Bottles’ is a song about how when memories form, especially when we’re younger, they can take on an almost mythical quality in our imaginations and dreams. Then as we grow older and that spell of innocence is broken, we leave them behind, only to return to them again later when they likely don’t resemble anything like what they originally looked like. After losing my mom, writing songs became a way to preserve memories, even painful ones from when I was a kid. Sometimes even difficult memories can sweeten and soften with time. I was exploring a lot of open tunings with this new album, and felt a bit like Dylan on Blood On The Tracks – something about playing in open D on this Martin opened up a new space and new ideas for me and reminded me of being a teenager exploring the same tunings. It’s funny how things make their way back around.” – Alex Mason

Video Credit: Bradley Pearson, Don River Music

Bob Sumner, “Motel Room”

Artist: Bob Sumner

Hometown: Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Song: “Motel Room”

Album: Some Place to Rest Easy

Release Date: September 6, 2024

Label: Fluff and Gravy Records

In Their Words: “There is a rapper/DJ named Channel Tres. Everything Channel does is cool. He drips cool. I’m a big fan of his music, his aesthetic, and his videos. He has a video for a tune called ‘Weedman.’ It’s Channel and his homies hanging out in a home ordering weed from their dealer. Throughout the video they break into dance routines. It’s chill af. It’s funny. It’s joyous. It doesn’t take itself too seriously. I wanted that for ‘Motel Room.’

“I wrangled two of my close friends, Logan Wolff & Matty Beans. I knew they’d be down. My partner Mica Kayde choreographed a dance routine for us. With my director Dana Bontempo and his partner Zara, we loaded into my pickup truck, brought Endo my tripod dog (and best friend), and spent three days on a road trip messing around. We danced in front of a motel called El Rancho in the interior of B.C. We went to the Armstrong Fair & Rodeo. We laughed a lot, mostly at ourselves, and we had the time of our lives doing it. It’s no Channel Tres, but I think we did what we set out to do. The video turned out to be a joy. It’s fun. It’s funny. It encapsulates those magical carefree years I spent with my friend. At the end of the video the character ends up alone in a motel room wantonly gazing out the window. We felt that was a part of the story we couldn’t leave out.” – Bob Sumner

Derek Vanderhorst, “Be Kind” (featuring Steve Poltz)

Artist: Derek Vanderhorst

Hometown: Golden, Colorado but moving to Nice, France in September

Song: “Be Kind”

Album: Be Kind

Release Date: July 12, 2024

In Their Words: “I wrote ‘Be Kind’ in a fun, humorous way to address serious issues that are dividing friends and family and loved ones. Racism and intolerance are making their way into our everyday experience and becoming somewhat normalized. The divisiveness is becoming so overwhelming that it’s now hard to have these serious conversations and I wanted to send the simple message of acceptance, love, and kindness – as well as [pointing out] differences are what makes life so great and worth living.

“As Gen Xers, we need to be open, aware, and embrace all the progress and change, not forgetting our generation’s great changes. We sometimes need to remember that we need change to have stagnant waters.” – Derek Vanderhorst

Track Credits:

Derek Vanderhorst – Music, lyrics, guitar, vocals

Steve Poltz – Vocals, guitar

John Mailander – Fiddle, mandolin

Frank Evans – Banjo

Brook Sutton – Bass

Jamie Dick – Percussion

The Doohickeys, “Rein It In Cowboy”

Artist: The Doohickeys

Hometown: Los Angeles, California

Song: “Rein It In Cowboy”

Album: All Hat No Cattle

Release Date: January 24, 2025

Label: Forty Below Records

In Their Words: “We wrote ‘Rein It In Cowboy’ after Haley got her butt grabbed in a bar… He copped a feel and we copped a song. The unsettling vibe you get from a creepy guy groping you is eerily similar to the feeling zombies evoke, which is why our video draws inspiration from our love of classic zombie films like Night of the Living Dead and Dawn of the Dead. We had a blast coming up with t-shirt pick-up lines and other visual jokes throughout the video. With the help of our friends, we crafted a visual narrative we’re truly proud of and can stand behind (and grab).” – Jack Hackett, The Doohickeys

Steven Moore & Jed Clark, “New Camptown Races”

Artist: Steven Moore & Jed Clark

Hometown: Jed Clark lives in Nashville, Tennessee, originally from Searcy, Arkansas; Steven Moore lives in Saint Clairsville, Ohio, originally from Bethesda, Ohio.

Song: “New Camptown Races” (by Frank Wakefield)

Release Date: June 26, 2024

In Their Words: “We are very excited to share our music video of ‘New Camptown Races,’ a tune by the late Frank Wakefield (June 26, 1934 – April 26, 2024) that has become a bluegrass standard. The idea for this video began at SPBGMA 2023, when we jammed to ‘New Camptown Races’ with both of us playing it in B-flat without using capos. We laughed and agreed that we needed to record it and maybe do a video shoot of it someday. It wasn’t until a year later at SPBGMA 2024, when we met up again, that we really solidified plans to make the video happen. Our hopes were to record the video and put it out on June 26, 2024 in honor of Frank’s 90th birthday. Unfortunately, the world lost Frank two months before he turned 90, but we decided to still aim to put out the video on what would have been Frank’s 90th birthday, in his memory…” – Steven Moore

Photo Credit: Rose Cousins by Lindsay Duncan; Reckless Kelly by Cassy Weyandt.