With a strong blue-collar approach to their craft, the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys have been running full throttle ever since forming in 2014 as the house band at Ole Smoky Moonshine Distillery in Gatlinburg, Tennessee. Bandleader and mandolin player C.J. Lewandoski says the group embraced the opportunity of “paid practice,” much like J.D. Crowe & The New South did at Lexington, Kentucky’s Red Slipper Lounge in the 1970s. The distillery shows offered traditional bluegrass covers, deep cuts from artists they’re influenced by, and requests mixed in with originals — a heavy mix that always kept their listeners (and often themselves) on their toes.

That same musical direction has been revived on the band’s second album, Never Slow Down, released by Smithsonian Folkways. The new collection sees the now-quintet tackle songs from their musical mentors like the Stanley Brothers, Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard, George Jones, and Jim Lauderdale, along with originals penned by guitarist Josh Rinkel.

In the case of “Ramblin’ Woman,” the cover not only honors Dickens and Gerrard but also acts as the official introduction of fiddler Laura Orshaw to the group, who handles lead vocals on the song. Calling in from their homes in East Tennessee and Boston, Lewandowski and Orshaw spoke with The Bluegrass Situation about how they complement each other musically, how they’re educating and keeping the bluegrass tradition alive, and how Lewandowski came to own Jimmy Martin’s pickup truck.

BGS: C.J., what do you feel like Laura has brought to the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys. And Laura, what do you think the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys have done to push you musically?

Lewandowski: We started as a core of four guys and weren’t even looking to add a fifth piece. At the same time we knew that if we ever did expand it would be with a fiddle. We didn’t want someone coming in that didn’t gel with our musical family. Over time we began bringing different fiddlers with us whenever we had extra money or if the promoters wanted one, but it never fully clicked with the band until Laura came along. She’s helped elevate our sound to a completely different level, one we didn’t even know we needed. She brings so much light to the stage and is very helpful with managerial stuff and structuring harmonies. Even without her fiddle she brings so much to the group with her harmonies. Laura, Jereme [Brown] and I could sing a song; she could lead a song on her own; or I could sing low while Jereme sings middle and she covers a high baritone. Her presence has added so many twists and turns to our music that has helped breathe new life into the songs.

Orshaw: The first time I saw the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys I was intrigued by their energy and all of the interaction between band members on stage. And like CJ said, with four out of five members having the ability to sing lead vocals, the possibilities are endless with what you can do. Everyone has their own unique style and influences that only give more personality to the songs. At the same time, whenever we join forces on harmonies, our voices all blend together seamlessly. Growing up in Pennsylvania it was always difficult finding younger people to play bluegrass music with who were doing their own thing and not just redoing what Flatt & Scruggs or The Stanley Brothers did. That’s what I love about the Po’ Ramblin’ Boys. They very much honor the tradition of bluegrass while at the same time carving their own path in the genre.

Going off that, what are your thoughts on using your music to carry on the bluegrass legacy, helping to keep the tradition alive?

Lewandowski: We’ve always carried that tradition of bluegrass with us. We love how we were raised, the people who have invested in us and the history of the music and will always carry them with us. At the same time, it’s important to us to leave our own mark on the music as well. For instance, with some of the songs Josh wrote it wouldn’t be far-fetched to question if they were written 50 years ago or yesterday. Other songs like “Ramblin’ Woman” act as both an introduction of Laura as a band member and us paying homage to Miss Hazel Dickens.

On “Woke Up With Tears In My Eyes” I’m paying tribute to Damon Black, a farmer turned songwriter from near my hometown in Missouri. In a similar fashion, “The Blues Are Close at Hand” honors Jereme’s dad, Tommy Brown & The County Line Grass. Not everyone is as in-depth on this music as we are, though, which makes it fun when they get one of our CDs and turn it on to play. The song is all new to them, and our hope is that listeners will fall in love with these songs and dive down the rabbit holes of the discographies of the artists who originally wrote them.

It sounds like your mission of preserving the bluegrass tradition led to a perfect marriage between the band and Smithsonian Folkways. How did that partnership come about?

Lewandowski: Smithsonian Folkways has been doing just that, preserving the tradition of bluegrass and American roots music, since 1946. Back then they were traveling the backroads of America, knocking on people’s doors and capturing the music of the country. Much like it was back then, it was them that approached us about partnering. I met John Smith, associate director of Smithsonian Folkways, at Leadership Bluegrass during the IBMA conference in 2017. We didn’t talk much then, but a few months later we were playing Pickathon in Oregon and he approached us there. I remember him asking how things were going with Rounder Records, our label at the time, before saying that Smithsonian would be interested in working with us at some point.

I held on to that invitation for a while. Not long after we decided to take the leap with them. It’s a natural fit for us because John was a fan of the band before we were ever working together. He believed in our music, what we wanted to do and how we were doing it. We shared the mission of historical preservation while also continuing to make our own music in a living, breathing kind of way. As musicians, our hope is that whenever labels come to an end, their assets are donated for preservation purposes to Smithsonian Folkways to keep the history alive, and our partnering with them puts us at the head of it.

Orshaw: When the first generation of bluegrass musicians like Bill Monroe and The Stanley Brothers were making their music for the first time, they weren’t creating it with the mindset of having it sound 50 years old. They were just making something that was exciting and relevant to them and based on their experiences and influences this sound turned into what we call traditional bluegrass. Our influences are just that. We’re not trying to sound like our music is half a century old, but we are trying to think about their spirit of creativity. In their time they were creating something that had never been done before. We’re just trying to keep that same pioneering spirit alive, which has been a challenge, but a fun one to navigate.

View this post on Instagram

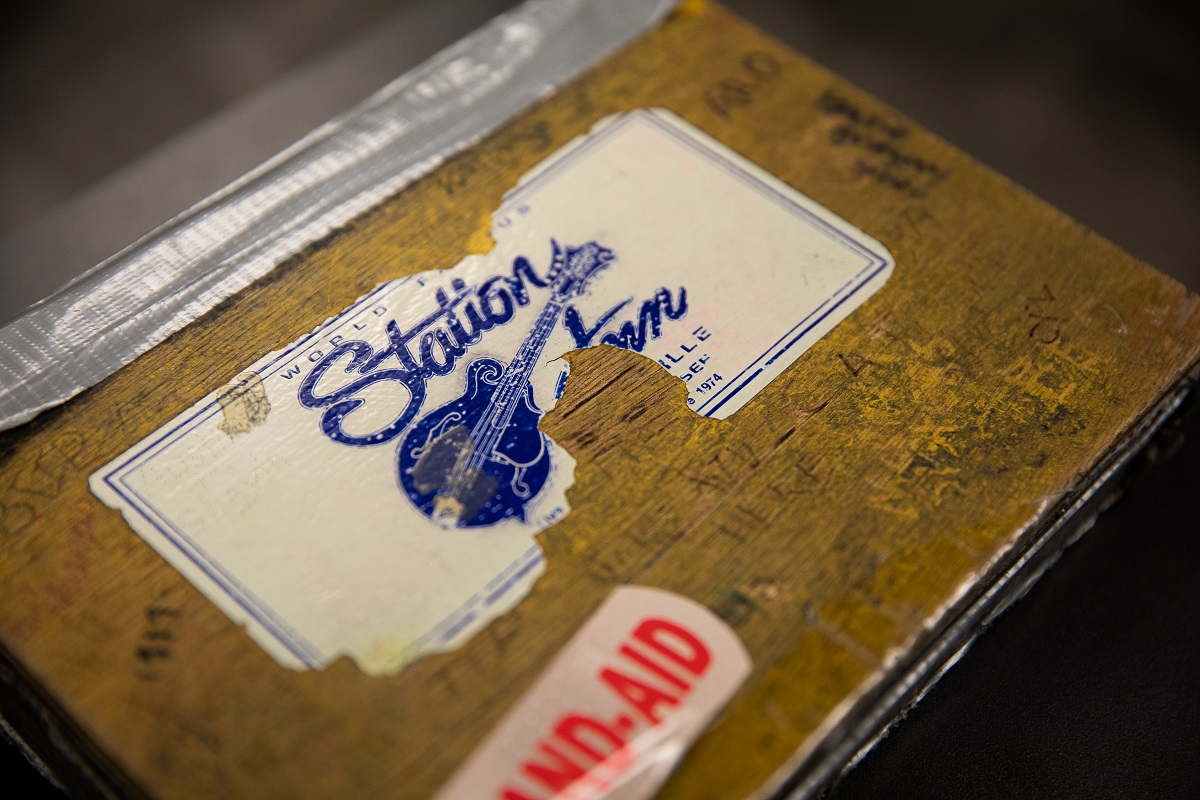

I know that another way you’re helping to preserve the bluegrass tradition is by showing off Jimmy Martin’s old pick-up truck during your journeys. How’d you go about getting that piece of history?

Lewandowski: It’s a living piece of history. I still drive it around all the time. People are always intrigued by it, and many of them don’t know who Jimmy Martin was. I’m always happy to tell people about him and stories about the truck. Even people who are familiar with Jimmy love it. In many ways it helps to open the floodgates for people to get into his music for the first time, or the hundredth time.

I got the truck from a friend of mine who was close with Jimmy. He had a Ford pick-up that Jimmy liked so the two traded trucks. He went and got the whole thing restored except for the interior that still has a busted window crank that Jimmy fixed with a bolt and rubber hose and a broken door handle that he replaced with a hook. One day I was at my friend’s house and saw the front of the truck under a tarp while he was trying to sell me something different. When he pulled the tarp up, I immediately knew what it was. I couldn’t believe it. After a couple years of negotiating, I finally got my hands on it. In addition to talking about it with everyday folks, I also got a call recently from Eastern Tennessee State University to come to campus and show the truck off to their bluegrass program. It’s as much an educational tool as it is a way to honor Jimmy’s legacy.

Photo Credit: Amy Richmond