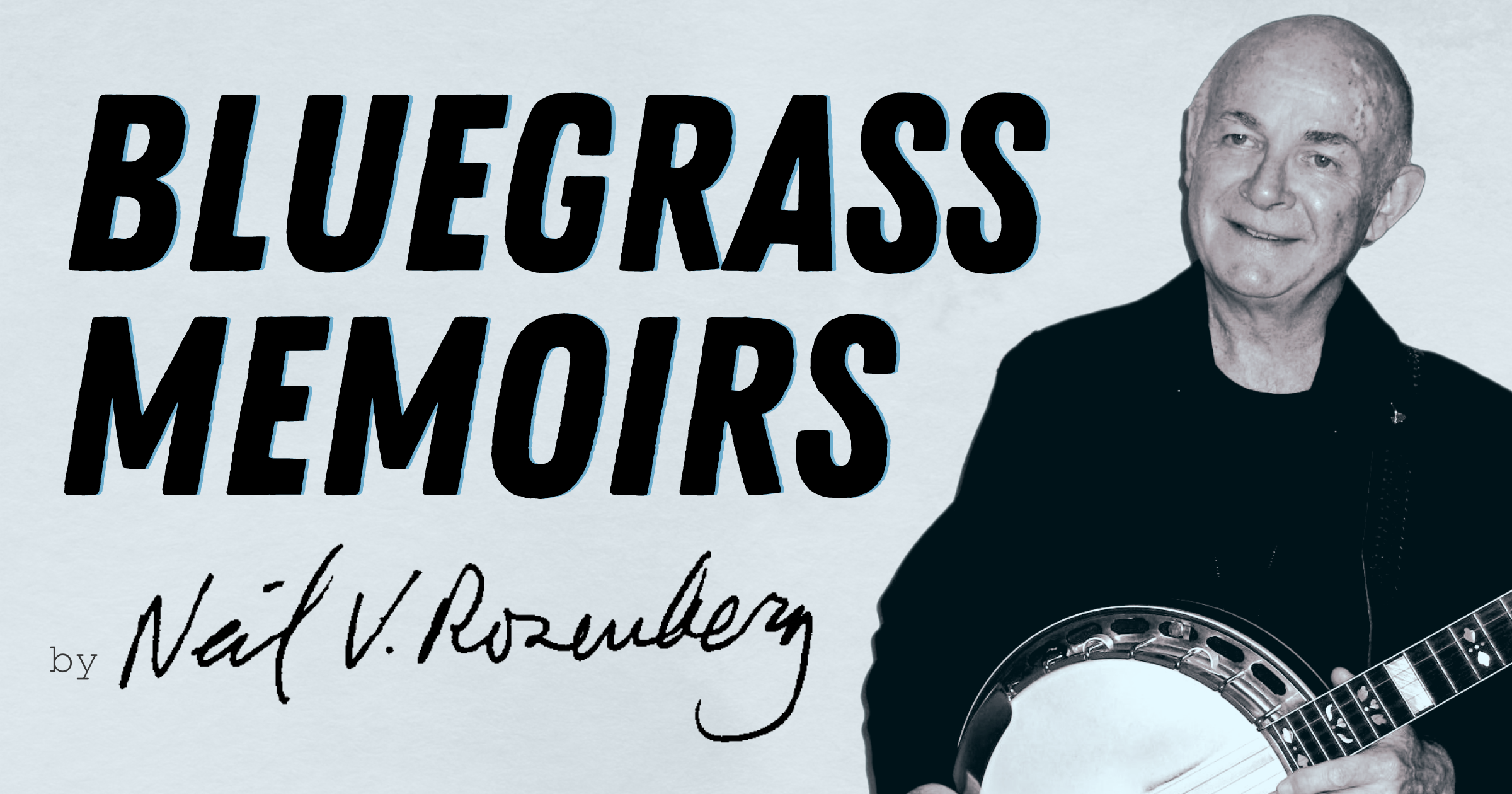

I’m rarely satisfied with the status quo. And I love roots music that is bona fide. Well, I’ve used up most of my Latin vocabulary very quickly.

I didn’t know what “Tempus Fugit“ meant until I got a wonderful new song from Tim Stafford and Missy Raines, both great artists, writers, and old friends. Missy and I were together with our bands at Americanafest in Nashville in 2024. I was chatting with her and said, “We’ve been doing this a long time,” since we got acquainted in the 1980s, as we were both learning everything about the bluegrass community. Missy said, “Yes, but we have heard so much great music and met so many wonderful people. And getting older isn’t a bad thing!” Then she told me she and Tim had a song about the subject. I had to hear it and I loved it!

Our new single, “Time Adds Up (If You’re Lucky)” is out just a few weeks after the new gospel album from JMRR was released in March. Thankful and Blessed is a collection of eight new sacred songs and two revived oldies. I’m grateful for the opportunity to deliver the spiritual message and provide an inspiring gospel collection, but I’m thankful for a great variety of music, and I’ve been blessed by the powerful talents of great musicians, singers and songwriters of all kinds.

So, this Mixtape is truly a mix – some songs from the past that inspire me, a tune from the current JMRR gospel album, and our latest bluegrass single from an album releasing in the near future. Carpe diem! – Joe Mullins

“Time Adds Up (If You’re Lucky)” – Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers

“Time Adds Up (If You’re Lucky)” is the new bluegrass single by JMRR. “Tempus Fugit” are the first words of the song, meaning time flies. The lyrics were so relatable for me at this phase of life. I have been on stage with a banjo and on radio in some capacity since 1982. Now, over four decades later, I have my first grandchild – and she’s gorgeous by the way!

I’m not just lucky, I’m thankful and blessed.

“My Ropin’ Days Are Done” – Blue Highway

Tim Stafford is such a great writer! This is a favorite recording of one of the most consistent bands of the past 30 years. Wayne Taylor sings with soul and the song is as lonesome as a one-car funeral procession.

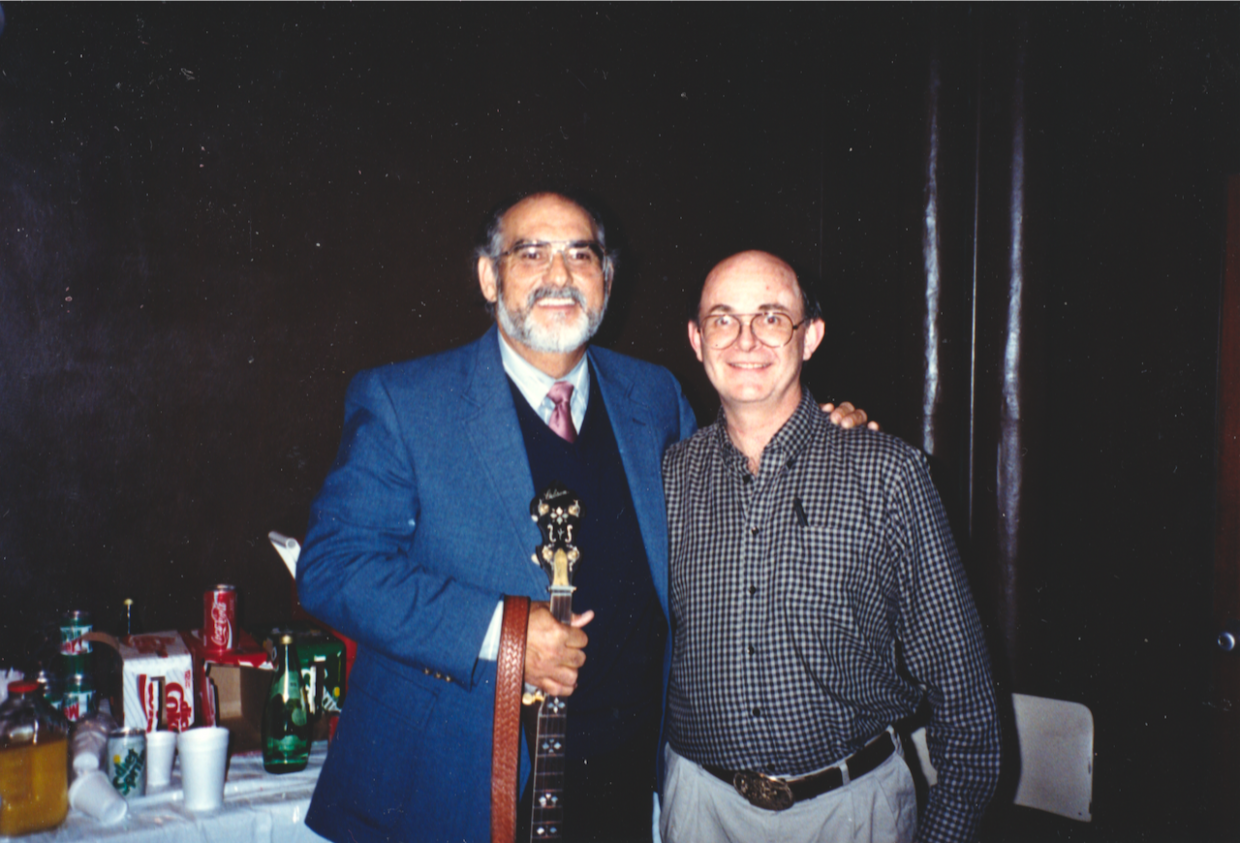

“Yardbird” – Larry Cordle

Music has to be fun sometimes! I love a good sad song, but clever lyrics that are so entertaining have been penned by Larry Cordle for years. And the mighty Cord is a great singer, too. Cord is also one of my favorite people, one of those who you always look forward to seeing. He’s been very supportive of my recording career, providing many songs. He and Larry Shell wrote “Lord I’m Thankful” in our new gospel album and a new working man’s song in the Radio Ramblers bluegrass album that releases soon.

“Andy – I Can’t Live Without You” – Ashley McBryde

She has such a believable delivery, and this song is gritty and sincere. The beauty of simplicity can’t be beat – a great voice, a killer song, and one guitar.

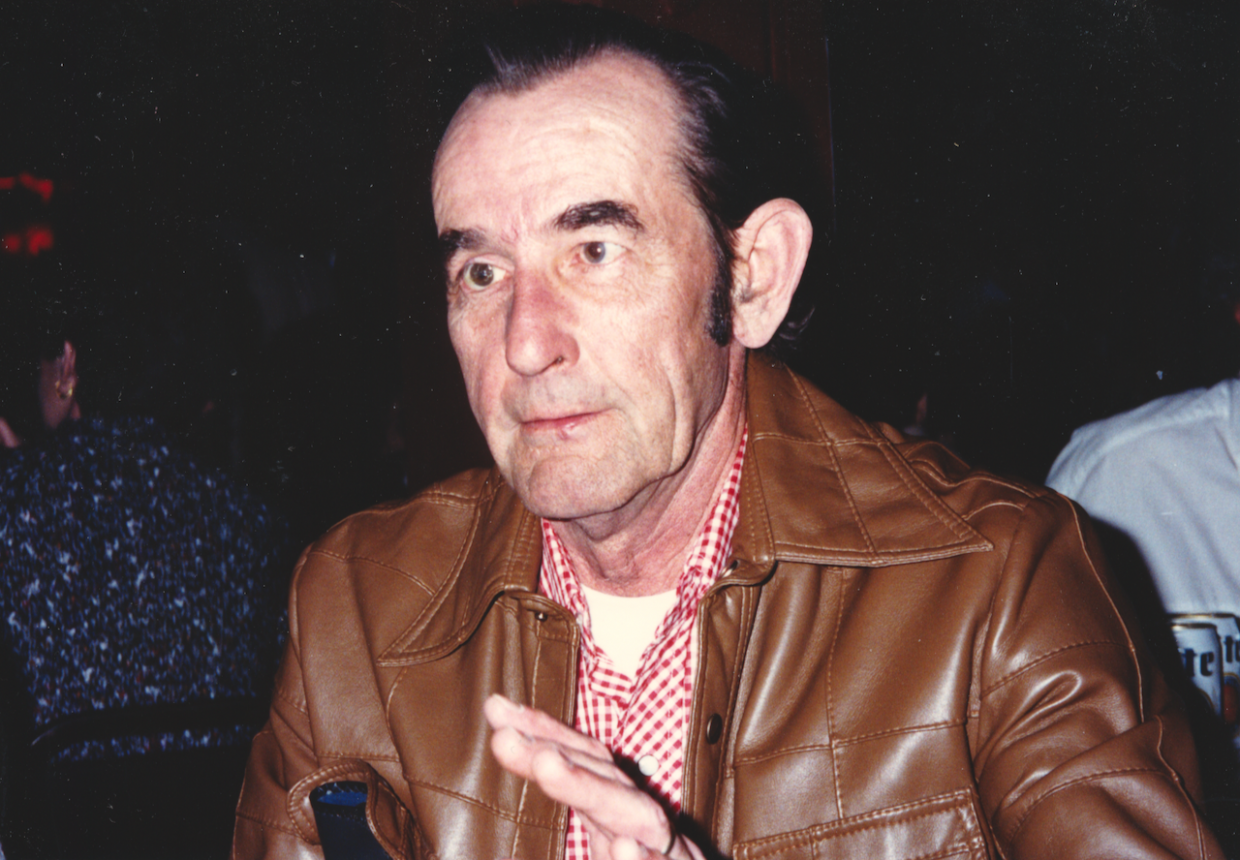

“Gonna Be Movin'” – Larry Sparks

Sparks is a stylist, both vocally and instrumentally. He’s an original in every way. I’m pretty sure he has his own zip code. Interestingly, Larry sings three of the four vocal parts in the quartet portions of this recording from the 1980s. Randall Hylton was a superb songwriter and performer whose home-going was way too soon. His bluegrass gospel songs will be enjoyed eternally and this is one of Randall’s best. I was fortunate to have a song from Randall’s catalog that was never recorded, and it’s the a cappella selection in our new album.

“Looking at the World Through a Windshield” – Daniel Grindstaff with Trey Hensley

One of East Tennessee’s great banjo men, Daniel Grindstaff, produced one of my favorite recordings of 2024. I love good, driving country music. I’ve managed a small network of radio stations for many years and we feature a lot of hard-hitting country music from every era. Daniel and Trey nailed this old truckin’ tune with a contagious, grassy groove.

“Beneath That Lonely Mound of Clay” – George Jones & The Smoky Mountain Boys

Yes, it’s a sad song. Graveyard tunes have always been part of the bluegrass and country canon. But I want the world to be aware of this album. Jones went to the studio with Roy Acuff’s band in the very early 1970s and recorded his favorite Acuff songs. The album wasn’t released until 2017. I’m a huge fan of George’s music from his six-decade career and he was in his prime here with an acoustic band that helped define country music on the Grand Ole Opry stage.

“Journey On” – Joe Mullins & The Radio Ramblers

If you’re enjoying the mixtape in order, we need something uplifting after our stop at the cemetery. This is a new song featuring the Ramblers quartet. The perseverance of the saints is celebrated in this tune from our new album Thankful and Blessed.

“From Life’s Other Side” – Lee Ann Womack

I was fortunate enough to produce an award-winning album during the pandemic. This song is on the 2021 IBMA Album of the Year, Industrial Strength Bluegrass. The album celebrates music I grew up on in my neighborhood, Southwestern Ohio. Dave Evans was an Ohio singer and songwriter with soul oozing out of every note he breathed, like Lee Ann Womack. Her treatment of one of Dave’s rare songs was a highlight of that album that is so special to me.

“Lonesome Day” – The Osborne Brothers

I must include an Osborne Brothers song, because I’ve listened to their music almost daily for my entire life. Bobby’s vocal delivery and Sonny’s banjo genius are among my greatest influences. This cut was produced about 1977. They went to the studio to record a collection of songs from their traditional bluegrass roots, after crossing over into mainstream country during the previous decade. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a more pure voice, and each instrument rings with huge tone because of the perfect touches, including Kenny Baker and Blaine Sprouse on fiddles, and the legendary Bob Moore on bass. Just turn it wide open on repeat!

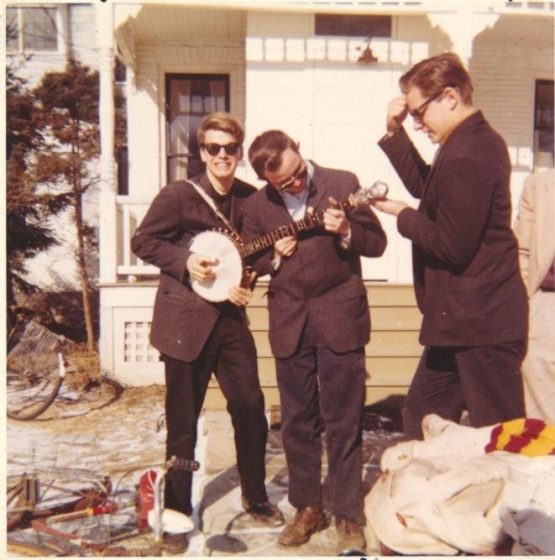

Photo Credit: Brandy Buckner