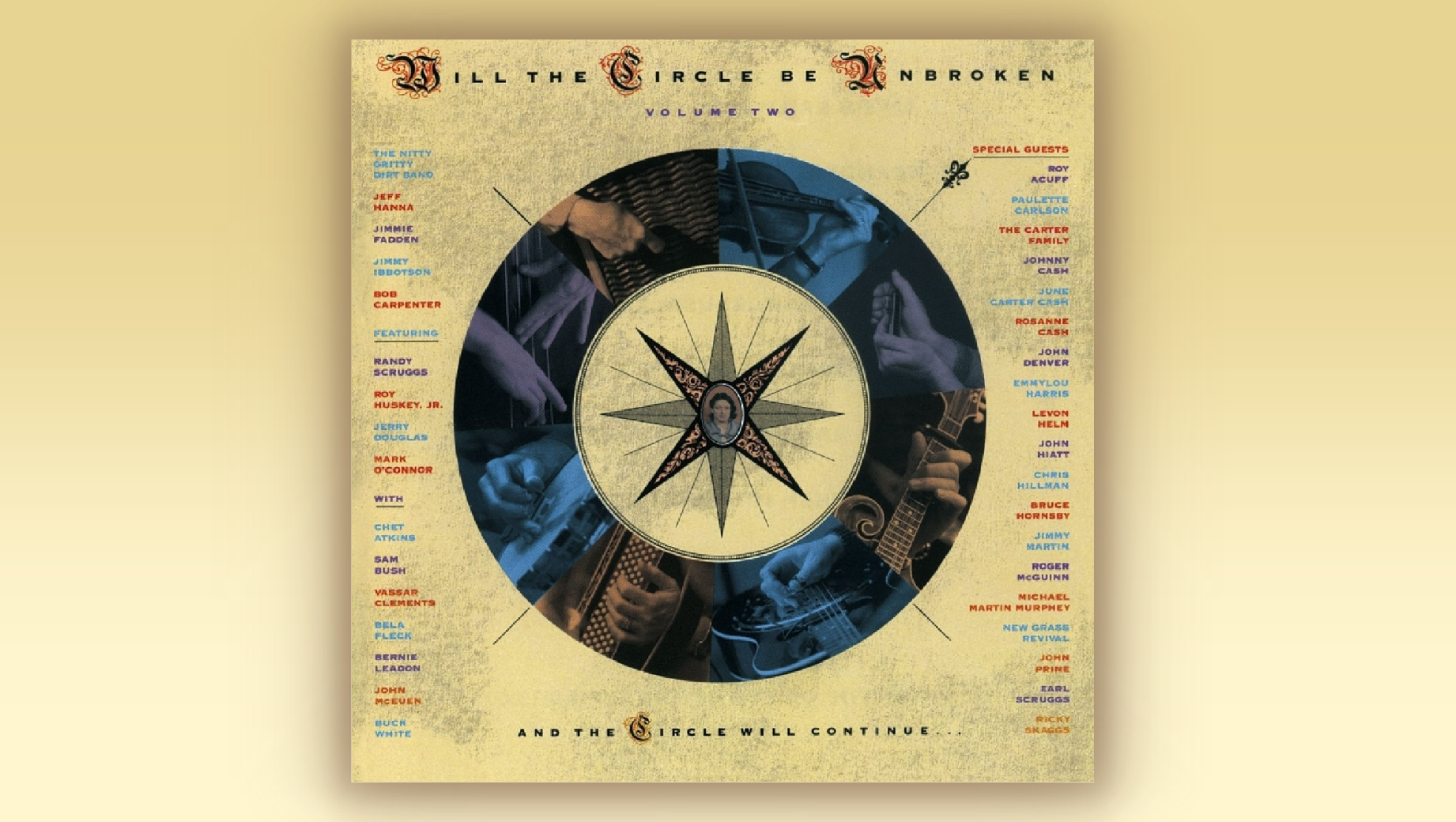

Why mess with a classic? That was the original thought from a few members of Nitty Gritty Dirt Band when the idea was presented to record a sequel to their seminal 1972 album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken.

However, with encouragement from one of the group’s biggest fans, the legendary June Carter Cash, the recording sessions for Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume Two commenced in the winter of 1988, with a cast of accomplished musicians who are now considered cornerstones of Americana music.

Often referred to simply as Circle 2, the acclaimed project was released in 1989 and went on to win three Grammy Awards and a CMA Award for Album of the Year. To commemorate its 30th anniversary, Jeff Hanna shares its back story with the Bluegrass Situation.

Editor’s Note: Jeff Hanna and guest Sam Bush will participate in a screening of clips from a documentary film, The Making of Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume Two, at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville on Wednesday, September 11 at 11 a.m., during AmericanaFest.

BGS: Can you explain why Circle 2 is such an important album for the band?

Hanna: It’s important in our history because at that point, we were no longer just the kids. We were all in our early 20s when we did the first Circle record, making music with those revered folks. And so we had a different point of view, somewhat. Here we were in the midst of our mainstream country career, and we still revered the first album.

The way we viewed Circle 1 was like something untouchable – just leave it. It is what it is. As time went on and as that project matured, it mattered a lot to a lot of people, including us. So we resisted the concept of doing another Circle record. Especially me, Jimmy Ibbotson, and Jimmie Fadden. Bob Carpenter was like, “I didn’t get to play on the first one! I wasn’t in the band! I want to do it!” He was pretty excited about the concept, and Chuck Morris, our manager at the time, brought it up a bunch. But we waited a while, and by the time it came out, it was 17 years between the releases.

When did you decide to move forward with it?

We were on tour with the Johnny Cash show, which included the Carter Family, and we were in Europe. I think it was in 1988 in Switzerland. June came into our dressing room — and she would visit us a lot. She was really sweet and she loved to talk about Mother Maybelle, and how much she loved us. She called us “them dirty boys.” I love that. And at the end of the conversation, she said, “You know, if you all ever thought about doing another Circle record, John and I would really love to take part in it.”

That was the tipping point. If you have that sort of endorsement from folks we idolized, and who were so important in the history of this music – and music in general — we thought, “Well, there you go.” That’s what we did. The winter of ’88, we started making calls.

How did you come up with the guest list, so to speak, for this one?

Our approach was to delve more into the next generation of folks, like New Grass Revival, and certainly a lot of our singer-songwriter buddies, like Bruce Hornsby, John Hiatt, Rosanne Cash, and John Prine. We had only recorded a little bit with Emmylou Harris and we really wanted to work with her. And we were really excited to do a record with Levon Helm. That was one of the highlights.

I think the collaborative spirit of this album really shines through when Bruce Hornsby is playing “Valley Road” with you guys.

I’d never met Bruce Hornsby but I was a huge fan of his music. I heard “Every Little Kiss” on the radio and it just blew me away. But then I’m reading an article in a magazine, and it was a “desert island disc” thing, talking about the records that you’ve gotta have, and he mentioned Will the Circle Be Unbroken. It was like, WOW! So I somehow got his phone number, I called him up — cold-called him — and he said, “Oh yeah, man, I love that record, I love you guys.” I said, “You’ve seen us play?” He said, “Yeah, my brother and I sneaked in.” We were playing a college show in his hometown, and those guys started carrying amps into the venue. We were unloading the truck and they started carrying gear in, and ended up sort of hiding behind the bleachers, and when the show started, came out and watched the show.

We hit it off right away, so there’s a direct line to Circle 1 right there. And when we were putting together our core band for the sessions, of course we included our buddy Randy Scruggs (who was on the first Circle album), Roy Huskey Jr. (whose dad Junior Huskey played on the first album), Jerry Douglas, Mark O’Connor… It was so much fun walking in and making music with those guys every day. Chet Atkins is on a track and played one of my guitars, which I liked. I know I’m never selling that guitar.

One of the coolest tracks on there is “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere.” How did that come about?

We brought in Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman, because the Byrds and the Flying Burrito Brothers were so important to us. The Byrds had done Dylan’s “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” but they wouldn’t play it on country radio, so we cut a version of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” with Roger and Chris, and it became a Top 10 country single, which we thought was cool redemption. We were really excited about being on the track with them. We still play that tune now and again. That’s one of our favorites. We’re really happy to have a good excuse to play it, because for years we played it in sound checks anyway.

It’s been 30 years now, but what do you remember about how Circle 2 was received upon release?

Perhaps because we had the platform of being a hit country band right about then, the label promoted the heck out of the record when it initially came out. And it had hits on it, that’s the other thing. Circle 1 didn’t really have any radio impact, whereas Circle 2 had “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” and we had a song called “When It’s Gone” that was a Top 10 single.

It’s a significant record and it’s funny, having been there from the get-go with this band, and having that first Circle record so deeply ingrained in my DNA, I sometimes forget how important Circle 2 was to a lot of folks. I’ve had more than one songwriter and musician tell me, “That’s what got me into you guys.”