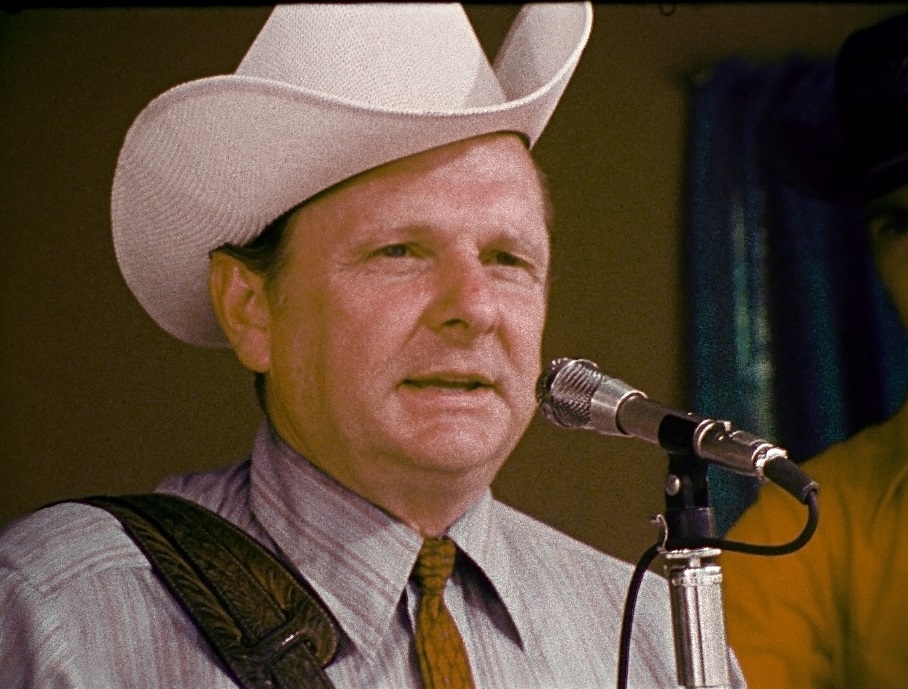

Russell Moore has been a professional musician and bandleader for 40 years and, though he wouldn’t describe himself as complacent, he does readily admit he generally knows what he can expect from that job.

“It’s almost like, ‘Okay, I know what this week is going to bring and what next week is going to bring,’” he shares over the phone. “It’s the same thing, even though you try to explore different opportunities … I never would have thought that at this point in my career that this opportunity would arise.”

Back in early December 2024, Alison Krauss & Union Station announced their first headline tour in nearly ten years and, with that announcement, that Moore himself would be joining the band. The bluegrass community responded with an outpouring of love for Moore, his talent, and his iconic, long-running bluegrass band IIIrd Tyme Out while marveling at how perfectly he and his voice would fit into one of the most prominent, best-loved, and best-selling string bands in music history.

Once fears of IIIrd Tyme Out being benched were totally allayed – the band has lasted 34 years so far and has no plans to curtail their efforts with Moore’s new gig – the ‘grass community set their sights on the next announcement from AKUS, which came in January: Arcadia, their first album since 2011’s Paper Airplane, will release March 28.

Arcadia will be the starting pistol for a breakneck six-month tour that will find Alison Krauss & Union Station (and their newest member, Moore) criss-crossing the continent to perform at some of the most notable venues and festivals in the scene. Many of which Moore will find himself checking off his bucket list for the very first time.

To mark the occasion, and as we anxiously count down the weeks to Arcadia and the Arcadia Tour, we sat down with Russell Moore to chat about his career, his plans for IIIrd Tyme Out, and how energized and excited he is by this once-in-a-lifetime chance. As he puts it, he has very big shoes to fill – but perhaps he is the only one concerned about having the chops to fill them.

You’ve been leading your own band for so long and you’ve been the person to “make the call” – hiring a sideman, or hiring someone to fill in, or finding a new band member. So how does it feel at this stage in your career to get this kind of call to join a band like Allison Krauss & Union Station? How does it feel to be on the receiving end for a change?

Russell Moore: What a blessing. It’s definitely the other side of the fence! For 34 years I’ve been running IIIrd Tyme Out and making the decisions or helping make the decisions. That’s a job in itself. You wear many different hats when you’re doing that.

The last time that I was in a situation like I’m going into with AKUS was back when I was with Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver. That was basically, “I’m the guy that plays guitar and I sing” and everything else was pretty much taken care of. Since then, up ‘til now with IIIrd Tyme Out, I’ve been heavily involved with all the decisions and making things happen, which like I said, it requires several different hats to wear day-in and day-out.

This is going back to that time, before IIIrd Tyme Out. And I’m excited about it. It really gives me the opportunity to focus totally on the music and my part in the band, rather than anything else that goes along with running a band. That’s exciting in itself. I will say, it’s going to take some getting used to, because I know that I’m going to be saying, “Oh, what can I do today to help this thing out?” That’s going to be a change of pace for me!

But I’m looking forward to it. Honestly, I’m looking forward to not having to worry about anything else other than my position in AKUS and just doing my job to the best of my ability and that’s it. That’s gonna be pretty cool. I guess you would say a little weight off of my shoulders.

You can set down the CEO hat and pick up the “being an instrumentalist and a vocalist and a technician” hat. Of course it’s got to feel exciting in some ways to get to step back into that role of being an equal part collaborator in a band instead of having to wear so many hats and having to be a lightning rod for everything.

RM: It is. It definitely is. I did experience just a little bit of this a few years ago. Jerry Douglas called and asked if I could go out for a few days with the Earls of Leicester, which I did and it was the same thing. I played mandolin and I sang my harmony parts with Shawn [Camp]. And I didn’t have to do anything else. That was all I had to do. For a few days there, I got to relieve myself of all the responsibilities of running a touring band on the road, and it was cool. I enjoyed it. I really did.

I’m not going to lie, I’m not saying that I don’t enjoy running a band, I’m not saying that whatsoever! But it was nice to step back for a few days and just be that. So I see this, for the six months between April and September, being sort of in the same picture. I wanna focus everything I can, all the time I’ve got, on playing the music, being in the position that I’m in, and doing the best I can. Just focusing on that. That’s going to be cool. I’m not going to have to worry about, “Did the bus get there on time? Is there something wrong with the bus?”

I know I’m not the only one who was super excited to hear this news and also thought immediately, “I never would have connected these dots myself, but who else has a better voice for that gig?” You think of Dan Tyminski, of Adam Steffey, the guys who have been singing vocals in this band, they have that sort of warm, honeyed, Mac Wiseman-like bluegrass voice – less of the high lonesome and piercing, even though you have the range and you can get up there, too.

So many people’s reaction to the announcement was that you have a voice that’s perfect for this gig and for what we all come to expect as the AKUS sound. Did you have that realization too? Did you think, “Oh yeah, this is perfect for my voice”? Or did you feel like, “I’m going to have to work at this.”

What was your general reaction, musically, to coming into this? Not just as a guitarist, but also as a vocalist – and then, I assume you’ll be playing some mandolin too, like you said you were doing with Earls of Leicester. So how are you approaching it musically?

RM: I will be playing a little bit of mandolin, not a whole lot, but my main gig I guess you’d say would be playing guitar and vocals – harmony vocals and some lead vocals as well. I’ll be honest with you, Justin, I was concerned about some of the harmony singing. That’s the biggest thing.

It’s really intricate.

RM: It is very intricate! It’s not in the same breath that I usually sing at. I tend to sing very full throated. For lack of a better term, it’s a male voice trying to sing very high. I do it in a robust way. I do have subtleties that I use as well, but this application of trying to blend with Alison’s voice is a different place to be, for me, for sure.

I do sing harmony and I have for years, here and there, but still my vocal technique has always been full throated and far more harsh, a male vocalist trying to sing very high. This is a different application. I tried to do that on all the songs that I’m going to be singing harmony on with Alison, it would be too abrasive. I’m learning how to make it work with my voice and her voice. That is a really nice combination, [you don’t want] me standing out because of my approach to the harmony.

Of course, I do have songs that I’ll be singing lead on. Those, I’m just back to my old self doing my thing. But when it comes to the harmony stuff, most of the time I’m having to really listen and focus on how to project my voice to make her sound as best as she can and not interfere.

Are you going to be singing lead on some of your own music with AKUS?

RM: No. There might be one song, and I’m not going to give away any of the stuff that she has planned for the set list, but there might be one song that people recognize from IIIrd Tyme Out during the performance. For the most part, this is Union Station. We’re not trying to bring in Russell Moore and IIIrd Tyme Out into the project whatsoever. We’re still around, we’re going to be performing when I’m not on the road with AKUS. There might be a small ode to IIIrd Tyme Out during the show, but it will be very small.

I’m not here to promote IIIrd Tyme Out with Alison Krauss. I’m here to promote Alison Krauss & Union Station and to be a part of that group and promote what this record release is and the stage show. I am a team player and I told them all, “You’ll never find anybody that’s more of a team player than I am, because I understand what that means.”

You’ve seen it on both sides. I’m glad you mentioned IIIrd Tyme Out continuing, because I think a lot of people’s natural reaction to the news was, “What about IIIrd Tyme Out!?” Of course IIIrd Tyme Out’s been going for so long, they’re gonna keep going.

RM: IIIrd Tyme Out is here to stay. When the conversations started about my being a part of Union Station going forward, I had a lot of questions. Can I do this? Should I do this? And that was one of them: “Will my band support me in this decision, or if I say yes, will they support me?”

[I consulted] my family, my wife, and everybody around me – it wasn’t a decision that was made quickly. I had to talk to people. Once I talked to my band members and I got their total support and thumbs-up affirmation – along with my wife, family, and friends – it was just like, “Okay, I have no reason not to do this. Everybody says I should and it’s a great opportunity.” At that point, I said yes.

Hopefully I can fulfill the position, because it’s not easy shoes to fill. I can tell you that right now I’m a huge Dan Tyminski fan. I have been since he came onto the scene way back – we’re talking Lonesome River Band days. He is so unique and his position with Union Station, until recently with his own band, that was the epitome of his career in my opinion.

Then, of course, he gets the head nod for Oh Brother, Where Art Thou? And the Stanley Brothers song, “Man of Constant Sorrow,” it’s still incorporated into his shows. I love the Stanley Brothers’ [version of the] song. I really do. But when I think about that song, I think about Dan Tyminski.

I guess the point is I’m a huge fan of Dan and his work. He is such an intricate part of what Union Station has been up to now. I think that those are big shoes to fill. I just hope I can facilitate that to everybody’s liking. I know there’s going to be some people that say, “No, it’s not Dan, it’s just not the same.” But I do want to say there are [many] eras of Union Station that were awesome, as well. You go back to when other people were in the group. Adam Steffey–

I’m partial to the Alison Brown era, too.

RM: Alison Brown! Oh, gosh, yes. Tim Stafford along that same time. I can’t say there’s been a bad ensemble for AKUS. It’s just evolved. And the fact that Dan was there for so long, that kind of solidifies that is the sound that most people – especially younger people who didn’t really start listening to AKUS until let’s say 20 years ago – are hearing. What they’re hearing is Dan Tyminski on guitar, singing harmony, and singing lead. That’s what they’re used to. That’s what they realize is AKUS music, and here’s this Texas guy coming in here trying to fill those shoes. I just hope I can satisfy everybody. I’ll do the best I can.

It’s gotta feel exciting, especially after having done something like this your whole entire life, to have that sort of childlike wonder at it feeling so brand new and so fresh. Even after you have done literally exactly this for so long, there are still things that you’re excited to accomplish and new territory you’re excited to explore. That sounds really energizing and really positive.

RM: It is energizing. I’ll be honest, Justin, I’ve been playing music full time for a good 40 years. That’s awesome. And at this point, after 34 years of IIIrd Tyme Out – I’m not going to say I’ve become complacent, but it’s almost like, “Okay, I know what this week is going to bring and what next week is going to bring.” It’s the same thing, even though you try to explore different opportunities and things that come within that.

But this, I never would have thought that at this point in my career that this opportunity would arise and I’d get to do something like this. Because, like I said, I’m not so much complacent, but I know what’s ahead. When the phone call was made and we talked, I had no idea that I had another option, another fork in the road. This is absolutely surreal, in a lot of ways, for me to get this opportunity and without giving up IIIrd Tyme Out. All the support from everybody that I know, like I said, there was no reason to say no.

Another part of this that I’m really excited about [is being] able to experience some of these places, these venues, these shows that I’ve never been to before. Just being able to experience it – like playing Red Rocks Amphitheatre – and just so many places that I’ve always wanted to go to and perform at. I’m going to get to do that!

Checking them off the bucket list.

RM: There you go. It wouldn’t be possible, I don’t believe, with IIIrd Tyme Out. I was always exploring new opportunities and things like that, but I don’t think it would have been possible to perform at some of these places without being a part of AKUS.

To me, “Looks Like the End of the Road,” the first single from the upcoming album, feels like classic AKUS. The So Long, So Wrong era is what it reminded me of first. You still have those tinges of adult contemporary, you have the pads and the synth-y sound bed underneath it, and it almost feels transatlantic a bit here and there. Overall, it sounds like classic, iconic Allison Krauss & Union Station. What are your thoughts or feelings on the single or what can you tell us about that first track?

RM: I think that the song is a great representation of what is coming out with the full album release, Arcadia. It is a great nod to Alison Krauss & Union Station music over the last several years and the last several recordings.

I think that the song itself is just well written and perfect for Alison to sing. There’s a small part of harmony vocals – and what I love about the way she constructs her arrangements is that it’s not overdone with harmonies. This is Alison Krauss & Union Station, it’s not just Union Station. So the focus is on Alison and her vocals. In my opinion, that’s the way it should be. This song doesn’t come out from the get go with a five-string banjo just blasting off. It’s a great construction of the arrangement and the vocals.I think it was perfect.

The only thing that people have said is that the title itself made them think that this was the end of Allison Krauss & Union Station! Which is so far detached from the truth. It was just the first single that was released. It’s a beautifully constructed song.

I will say, this song is just a piece of the puzzle to the rest of the recording. It just paints a beautiful picture and a wonderful listening experience. When people get to hear the full album, they’ll understand what I’m talking about. It’s just awesome. It’s just, it’s a piece of the puzzle.

You’re going to be blown away. Absolutely blown away, as I was. I had my headphones on. I can’t tell you how many nights before I’d go to sleep, I’d have my headphones on [listening]. I listened to it two, three times a night, just because it was so enjoyable. It was just that good. I know that everybody else is gonna feel the same way when they hear the whole project.

Photo Credit: Matt Morrison