Welcome to the BGS Radio Hour! Since 2017, this weekly radio show and podcast has been a recap of all the great music, new and old, featured on the digital pages of BGS. This week we have a previously unreleased live performance from Emmylou Harris and the Nash Ramblers, as well as Béla Fleck’s return to bluegrass, a conversation on songwriting with Rodney Crowell, and much more.

APPLE PODCASTS, SPOTIFY

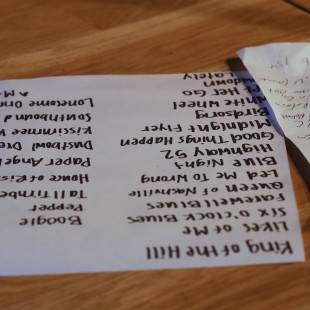

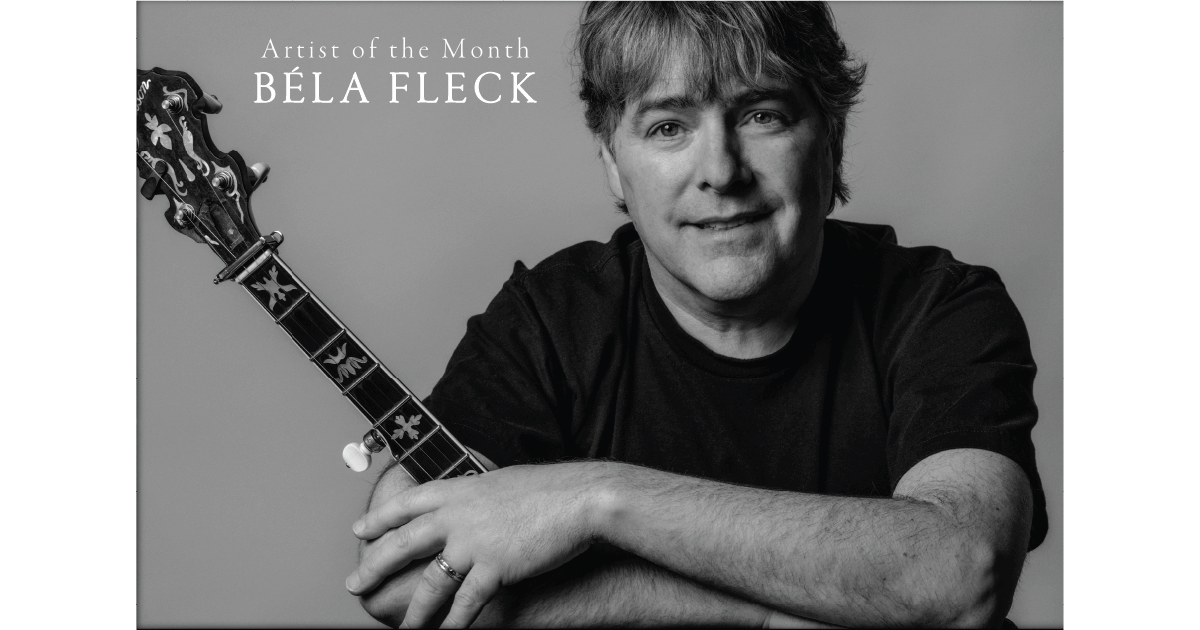

Béla Fleck – “Round Rock”

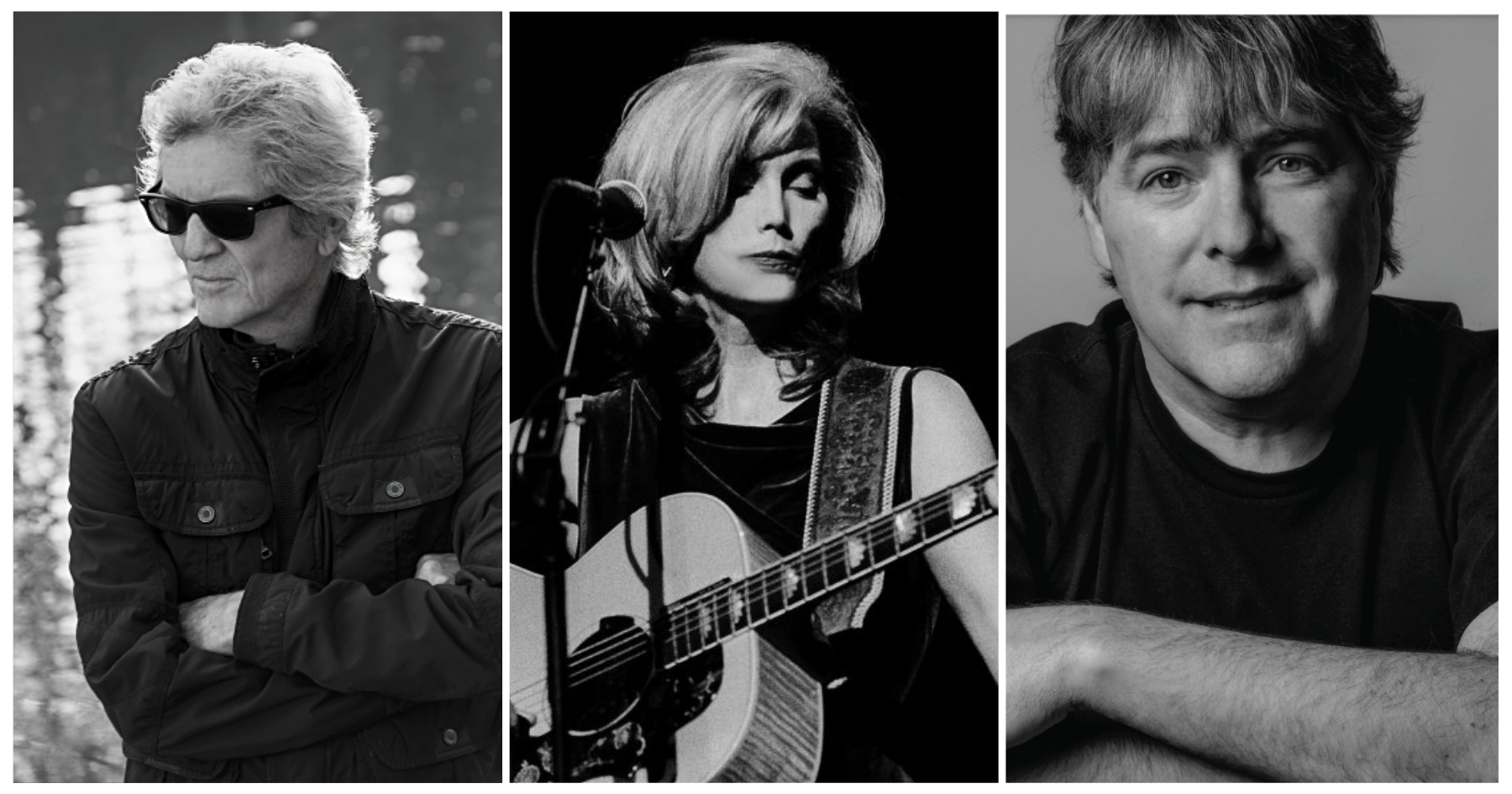

Our current Artist of the Month recently gathered an incredible crew of bluegrass power pickers for a live rendition of “Round Rock,” a tune that he included on his recent album My Bluegrass Heart, but that he had in his back pocket for nearly 20 years. He had been saving the piece for the right band to come along, and with this lineup, he has certainly found the players up for the task.

The Kody Norris Show – “Farmin’ Man”Kody Norris’ “Farmin’ Man” is a true-life account of the American farmer – from the perspective of Kody himself, who grew up in a tobacco farming family in the mountains of east Tennessee. “I hope when fans see this they will take a minute to pay homage to one of America’s greatest heroes…”

Katie Callahan – “Lullaby”Katie Callahan wrote “Lullaby” on the edge of the pandemic, before anyone could’ve imagined the way parenting and work and school and home could be enmeshed so completely. The song became a sort of meditation for her amidst the chaos.

Della Mae – “The Way It Was Before”

For Della Mae’s Celia Woodsmith, the process of writing “The Way It Was Before” was one of the toughest. [The song] “took Mark Erelli and I six hours to write (three Zoom sessions). Half of that time was spent talking, looking up stories, getting really emotional about the state of the world. We wanted to make sure that every word counted, so we took our time and tried to honor each of the characters (who are actual people). The pandemic isn’t even behind us, and yet I keep hearing people say that they can’t wait to get back to “the old days.” There’s so much about “the old days” that needs changing. After everything we’ve been through in the last 18 months, I found that writing a song like this felt impossibly huge. I may not have finished it if it hadn’t been for Mark.”

Ross Adams – “Tobacco Country”The inspiration behind singer-songwriter Ross Adams’ “Tobacco Country” came from the idea of always staying true to your roots and remembering the people who helped you follow your path and dreams.

It’s a track paying tribute to the South.

Swamptooth – “The Owl Theory”Savannah, Georgia-based bluegrass band Swamptooth wrote this jammy, energetic tune based on a Netflix series and true crime mystery with an unlikely theory that involves an owl. Read more from Swamptooth themselves.

Emmylou Harris & The Nash Ramblers – “Roses In The Snow (Live)”

A September 1990 performance by Emmylou Harris and the Nash Ramblers at the Tennessee Performing Arts Center in Nashville had been lost to time, but now, Nonesuch Records has released it as a new live album, which features a slew of songs that were not performed on the iconic At the Ryman record.

Jon Randall – “Keep On Moving”“‘Keep On Moving’ started with a guitar lick and a first line,” Jon Randall tells us. “Once I put pen to paper, I never looked back. That’s exactly what the song is about as well. Sometimes I wish I could just get in the car, hit the gas and keep going. I think we all feel that way and probably hesitate to do so in fear of finding somewhere you don’t want come back from. What if there is a place where nobody gives a damn about where you come from and the mistakes you’ve made? That would be a hard place to leave.”

Fieldguide – “Tupperware”“Tupperware” came to Canadian singer-songwriter Field Guide all at once in about 20 minutes. It’s a song about his early days living in Winnipeg, but it’s also more generally about the beautiful parts of life that aren’t meant to last forever, and coming to terms with that.

Rodney Crowell – “One Little Bird”Courage and truthfulness. Those qualities permeate Rodney Crowell’s new album, Triage; in fact, it’s safe to say they’ve guided Crowell’s entire career. In our latest Cover Story, we spoke to Crowell about the new project, making amends, mortality, and so much more.

“I learned a long time ago,” he explains, “If it’s coming from my own experience, there’s a good chance I’m a step closer to true. And I can mine my personal truth, but confessional only goes so far. I’ve tried to walk that line; if I can carefully write about my own experience and put it in a broader perspective, then [for] the listener, it becomes their experience…”

Triage, as specific and particular as it gets, feels like it contains truth that belongs to each and every listener. “That’s why I feel like I have to be really careful; if I make it too much about my experience, then I start to tread on the listener’s experience.”

Suzanne Santo – “Mercy”In a recent edition of 5+5, Suzanne Santo shared her thoughts on the emotional alterations of cinema, the gift of playing music for a living, taking long, rejuvenating walks, and much more.

Jordan Tice (featuring Paul Kowert) – “River Run”Hawktail members Jordan Tice and Paul Kowert collaborated on an original tune, “River Run,” during lockdown. According to Tice, the song “started with a little lick I had been carrying around in the key of D — a speedy little cascading thing that felt good to let roll off the fingers that I’d find myself playing in idle moments.” The end result evokes the lightness and constancy of a swiftly moving river as it passes over rocks, rounds curves, and speeds and slows. “[I] hope you experience the same sense of motion while listening and are able to glean a little bit of levity from it.”

Skillet Licorice – “3-In-1 2 Step”Skillet Licorice combined a few different old-timey, ragtime, swinging melodies into a sort of parlor song medley that feels like it came straight out of Texas, complete with banjo and mandolin harmonies.

Photos: (L to R) Rodney Crowell by Sam Esty Rayner Photography; Emmylou Harris by Paul Natkin/Getty Images, circa 1997; Béla Fleck by Alan Messer