There is no disputing that Tom Paxton is a living music legend. In the early 1960s, he was a major player in the vibrant Greenwich Village folk scene, along with the likes of Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Peter, Paul & Mary. The writer of such classic tunes as “Last Thing On My Mind,” “Bottle Of Wine,” “I Can’t Help To Wonder (Where I’m Bound),” and “Ramblin’ Boy,” Paxton has earned Lifetime Achievement Awards from the GRAMMYs, ASCAP, and the BBC. The beloved songwriter has had his tunes covered by a wide spectrum of acts, ranging from Harry Belafonte and Neil Diamond to the Pogues and Norah Jones. While several fellow singer-songwriters (notably Carolyn Hester and Anne Hills) have devoted entire albums to Paxton music, it took a group of admiring bluegrass musicians to deliver the first multi-artist tribute album of his songs.

Bluegrass Sings Paxton, which came out August 30 on Mountain Home Music Company, offers an impressive lineup of contributors that cuts across several generations of bluegrass musicians. Performers include celebrated acts, such as Alice Gerrard, Claire Lynch, Laurie Lewis, and Tim O’Brien along with younger stars, like Sister Sadie, Della Mae, Steep Canyon Rangers’ singer/guitarist Aaron Burdett, Unspoken Tradition’s Sav Sankaran, and current IBMA Male Vocalist of the Year Greg Blake.

Paxton, speaking to BGS from his home in Virginia, said that he had a mostly hands-off role in the making of Bluegrass Sings Paxton. “I just sat on the sidelines in amazement”; however, he confided, “I was just blown away” after listening to the entire album for the first time. The 86-year-old singer-songwriter was also being a little modest about his own contributions. This collection contains two new Paxton tunes, and he sings on a pair of tracks as well.

The genesis for Bluegrass Sings Paxton started with a conversation that GRAMMY-winning musician/producer Cathy Fink had some years ago with Paxton, who she has worked with since the early 1980s and has known even longer. “I know Tom’s catalog really well and have often thought there was great material there for bluegrass,” she shared with BGS. “I could hear this album before we even began.” The idea further evolved a while later when Fink brought up the idea to award-winning songwriter, producer, and Mountain Home executive Jon Weisberger at IBMA a few years back, and he immediately came aboard.

Several of Paxton’s tunes have been very popular in bluegrass circles over the years. A half century ago, Kentucky Mountain Boys covered “Ramblin Boy” while the Dillards and the Kentucky Colonels were among those who have recorded “The Last Thing On My Mind.” More recently, “I Can’t Help But Wonder (Where I’m Bound)” was a hit for Ashby Frank and “Leavin’ London” is a live staple of Billy Strings’ concerts. However, both Fink and Weisberger thought the project was a terrific way to get Paxton’s deep songbook better known in the bluegrass world. As Weisberger explained, “I had no doubt that there were more [songs] – both already written and yet to be written – that would work well within bluegrass, and that bringing them to light would encourage artists looking for songs to look to his catalog.”

Several acts came into the project with specific songs that they wanted to do. Blake, who fatefully was sitting at the same table with Weisberger and Fink at IBMA, quickly put dibs on “Leaving London.” Danny Paisley, who remembered his dad, ’80s bluegrass star Bob Paisley, taking him to the Philadelphia Folk Festival as a child and seeing Paxton play there, requested “Ramblin’ Boy,” because it was a song his father had performed. “I Can’t Help But Wonder (Where I’m Bound)” was already part of Della Mae’s live repertoire, so doing that tune was a natural fit for them.

When it came to what songs other acts took on, Fink gave the performers a lot of free rein to delve into Paxton’s vast treasury of tunes, a decision that worked out wonderfully. “Each artist made the song their own and it really worked,” she confided. Claire Lynch chose “I Give You The Morning” and Alice Gerrard selected “The Things I Notice Now” from Paxton’s 1969 The Things I Notice Now album. Chris Jones picked “The Last Hobo” from 1986’s And Loving You. Paxton’s 2002 album, Lookin’ for The Moon, was the source for both Aaron Burdett’s selection of and Sav Sankaran’s rendition of the title track. Laurie Lewis, meanwhile, found “Central Square” from 2015’s Redemption Road. In case you haven’t done the math, these songs alone cover nearly 50 years of Paxton’s recordings.

Paxton, too, was thrilled with the selections, proclaiming “I liked every one of the songs that they chose.” While he expected tunes like “Can’t Help But Wonder,” “Ramblin’ Boy,” and “The Last Thing On My Mind” would be part of the set, Paxton said he “was just tickled to death” over the inclusion of such lesser known numbers as “Central Square,” “The Same River Twice,” and “The Last Hobo.”

Chris Jones revealed to BGS that he picked “The Last Hobo” because the tune “felt like a classic Tom Paxton third-person story song, sort of in the spirit of ‘Ramblin’ Boy,’ in a way. It has a kind of tenderness that is so often present in Tom’s songs.”

Jones was also a member of the de facto “house band” that played on the majority of Bluegrass Sings Paxton’s tracks. A secret weapon behind the album, this team of bluegrass all-stars includes IBMA award-winners banjo player Kristin Scott Benson (the Grascals), fiddler Deanie Richardson (Sister Sadie), and Jones on guitar, along with mandolinist Darren Nicholson (formerly of Balsam Range), bassist Nelson Williams (Chris Jones & the Night Drivers, New Dangerfield) and harmony singers Travis Book (The Infamous Stringdusters) and Wendy Hickman.

Jones felt that everyone “clicked well together” and gave the music “a natural sound, which helped give the impression that these were bluegrass songs to begin with, even if they weren’t.” He also credited producers Weisberger and Fink for “coming up with arrangements that really fostered that feeling, too.”

Bluegrass Sings Paxton opens with one of the tunes that Paxton sings on. He was able to join Della Mae on “I Can’t Help But Wonder (Where I’m Bound)” as the band was recording in Maryland, not too far away from Paxton’s home base in Virginia.

“We did it live in the studio. No overdubs or anything,” he revealed. “I had a ball doing that track with them.” Paxton also sang with long-time collaborators Cathy Fink & Marcy Marxer – the three did a double album, All New, together in 2022 – on the up-tempo love tune, “All I Want,” which is also one of the two of new Paxton tunes on the project. The other new number, “You Took Me In” is a co-write with Tim O’Brien and his wife Jan Fabricius. One of the first tunes he wrote with the couple, Paxton said that “it had to be chosen. It’s such a good song.” He described it as “gospel without being gospel,” adding, “I took the literal gospel out of it and kept everything else.”

Fink & Marxer and O’Brien & Fabricius are among the handful of musicians that the still highly-active octogenarian collaborates with via Zoom each week. Folk luminary John McCutcheon, Colorado troubadour Jackson Emmer, and the rising Pittsburgh band Buffalo Rose are also among his regular online songwriting coterie. Paxton says he sometimes writes three to five songs a week. “Lots of folks would retire to the golf course at this point in their lives,” Fink marveled, “but Tom is driven by writing the next song.”

Over the years, Paxton has penned hundreds and hundreds of songs, and more than 60 albums bear his name, beginning with 1962’s I’m the Man That Built the Bridges that was recorded live at New York City’s fabled Gaslight Club. Even from the start, Paxton filled his records predominately with originals, which wasn’t typical at that time. Dylan’s 1962 debut, for example, contained only two originals. Dave Van Ronk, in fact, famously proclaimed in his memoir that it was Paxton who kicked off the folk scene’s “New Song Movement,” not Dylan as often credited.

The best-known songs from his debut, somewhat curiously, are three tunes that might best be described as children’s music: “My Dog Is Bigger Than Your Dog,” “Marvelous Toys,” and “Going To The Zoo.” Writing and performing kids songs was not an isolated occurrence for Paxton, who went on to release several children’s albums, including the GRAMMY-nominated Your Shoes, My Shoes, and to write books for kids. Paxton very much sees himself as continuing the legacy of his heroes, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and The Weavers – artists who performed all types of songs, from story songs and ballads to children’s tunes and political songs.

“Everything I do is really rooted in traditional music,” Paxton elaborated during his phone interview. “I’m always going back to that well of traditional folk music, Appalachian music, cowboy music. It’s a wonderful tradition – great, great songs, and I just keep trying to write songs that feel the way they felt.”

Paxton cites one specific musician – the late, great Doc Watson – to explains his “best route” to bluegrass music. He saw Watson when Ralph Rinzler first brought him to play in New York City and came away so impressed. “I was very fond of him and adored his music. I think he liked me, too. Doc recorded many of my songs over the years.” He also remembered sharing a bill with Watson once in Tampa and being brought out on stage to perform “Bottle Of Wine.” Paxton was rather intimidated over Watson’s and his guitarist Jack Lawrence’s virtuosity. “Why do I feel like I’m wearing painter’s gloves,” he recalled saying while admitting “it was a lot of fun.”

Weisberger describes Paxton’s place in American music as a unique one. “He was an integral part of the transition from wholly traditional folk music to the more modern conception of the field, with its inclusion of performing songwriters, but where a lot of his contemporaries moved on in one way or another, he went deep rather than broad… I think that’s what makes so many of his songs sound so natural and organic and almost effortless. That is an artistry that is really easy to overlook or under-appreciate, so I’m happy to have put together a collection that will, I hope, bring more attention and appreciation to that still ongoing legacy.”

When asked how his songwriting has changed over the years, Paxton replied that he hopes it’s deeper and more developed, adding rather humbly that “I’m still the same writer I was when I wrote ‘Last Thing On My Mind.’ It’s like a farmer who puts in the same crop every year. It’s the same farmer.”

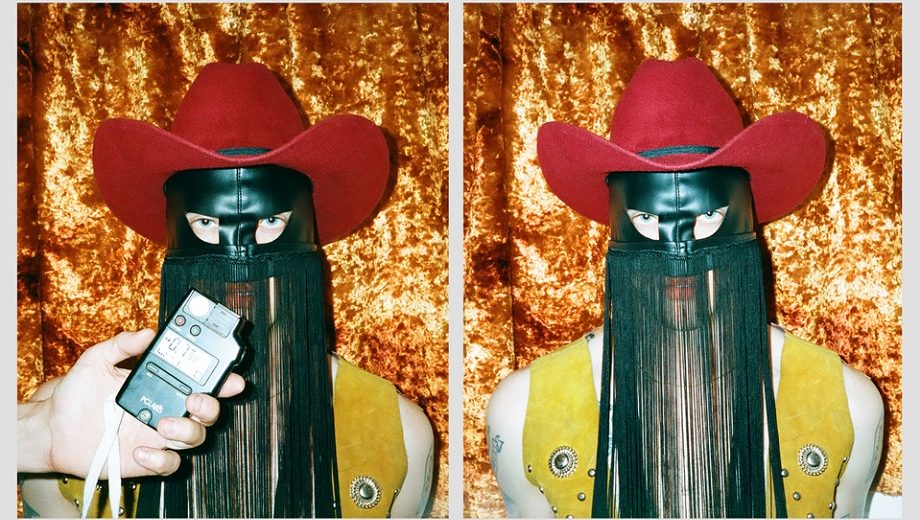

Photo courtesy of Fleming Artists. Album cover courtesy of Crossroads Label Group.