On Halloween, I released an album of griefwork music. Laments features four compositions for solo fiddle and voice born out of an instinctive and spontaneous draw into lamentation when my body demanded it as part of its healing processes.

In both my vocal and instrumental soundings, the role of a traditional lamenter has long been rooted in my identity and how I seek to be of service as a community member who helps others enter into emotion or move through to the other side of an emotion. That work is not limited to sorrow, but can move joy as well. Music can help to bring more aliveness and connectedness to one previously detached, as I’ve been lucky to experience in my work of being a dance musician or a wedding fiddler.

Since my initial education on the topic of “lament” around age 20 while studying in Helsinki, I have held the possibility of a similar role as a guide into or through feeling at the core of my work. It wasn’t until the middle of the last few years, when I had been writing this music on fiddle and voice, wailing music with few words, that I realized I was working with actual lament and that I had found myself knee deep in a river of tradition. So I am here, coming full circle.

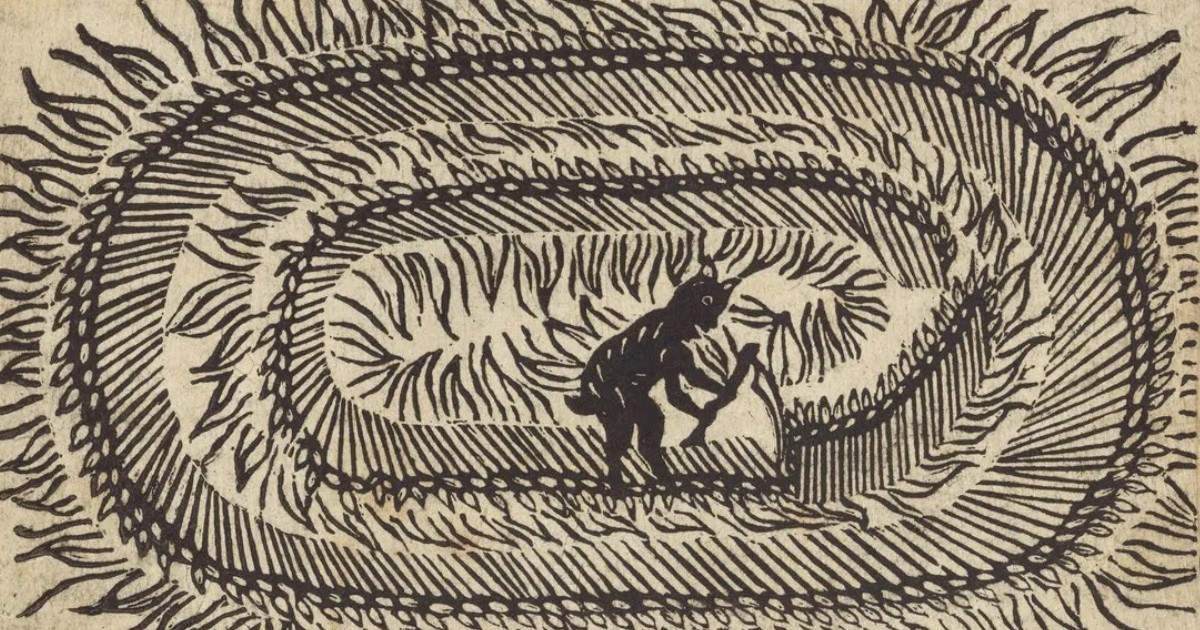

Seventeen years later, I returned to research and to listen to archive sources after I had birthed this work, to begin to understand the context of my path, to grab on to some railings, and to move into whatever comes next. I have since come to understand that performative ritualized mourning is a global phenomenon of traditional cultures. While my record is a performance of prepared arrangements and echos of what I experienced in liminal spaces, as opposed to my live lamentation or ritual, it’s my hope that the music can represent the shallows of what is available inside of the great depths of the tradition. (For more reflections on this work, read on via the extended notes booklet for Laments.)

For this Mixtape, I thought back through time to craft a collection of tracks that have been medicinal to me in seasons of heaviness, in times when I needed assistance to reopen a closed self. The tunes span many genres – please take them with open ears and meet them with what they offer. Through different modes, they all have the power to help bring in a glimpse or a full serving of transformation, whether that’s delivered from the quietest breath of the mechanics inside of a piano or from the wall of supportive pressure that is the embrace of the Scottish smallpipes. Three traditional lament forms are featured (Ireland, Scotland, and Peru) nestled here alongside music that I think works in related ways. It is music that helps us enter ourselves. – Laurel Premo

“Riverside” – Tim Lowly

This is the first song that came to my heart for this Mixtape, possibly because it was an early memory of the expansive potential of music as a tool in grief. I heard Tim Lowly sing this song at an intimate house concert in Kalamazoo sometime in the 2010-2015 range and his album traveled with me over many touring miles in America that decade. Tim is a painter and writer, and the central protagonist of much of his work has been his daughter, Temma, who has cerebral palsy with spastic quadriplegia. The melody and lyrics in this piece surrender to “slipping down” until they land on some solid new core.

“Pililiù” – Bridghde Chaimbeul

I’ve been very moved by the sounds from Scottish pipes player Bridghde Chaimbeul, who’s just recently completed her first US tour. I listened to her rendition of “Pililiù” during a high intensity breath practice once and it produced an immediate outpouring of tears. Some deep thread of connection existed there. A few months later, while researching vocal roots and lamentation, I recognized that this melody that she had recorded instrumentally is indeed an example of a traditional keening melody. The melody of this lament is a recreation of birdsong of the Redshank. In Scottish tradition, this coastal bird inhabits the liminal space between solid earth and the vastness of the fluid ocean, between known and unknown eternity.

“Body” – Emma Ruth Rundle

A few winters ago Engine of Hell hit me in a heavy way and seemed to be the exact medicine of resonating my own experience that was needed. When music reflects some color of what we’re feeling, it can vibrate our emotional body into become something bigger than we can see and relate to, converse with, question, and be held by.

“Visit Croatia” – Alabaster DePlume

This nostalgic journey is created from patience, deep listening, and real breath. Alabaster DePlume is an English musician and poet.

“Batonebo – Rachan” – Ensemble Ialoni

This is a pre-Christian healing song from an incredible Georgian women’s ensemble. In traditional Georgian belief, “Batonebi” is the name of spirit beings that are the cause of childhood infectious diseases. Songs like this are sung to these spirits, alongside other ritual, to appease them and ask them to leave the sick child so that they may heal. This whole record contains traditional folk song in complex harmony that work as chants for the singer and listener (including the Batonebi spirit audience!).

“My Friend The Forest” – Nils Frahm

Nils Frahm presents deep texture and intimacy here. The flex and breathing of the piano, akin to the live breath of the forest, takes you on a whispering trail of release. Other tracks that have a similar vibe from this record are “A Place” and “Forever Changeless.”

“Gorm” – Susan McKeown

I was introduced to this recording through the master’s thesis of Michelle Collins who investigated the de-ritualization and re-ritualization of keening in contemporary Ireland. This original song from 1996 is written in the traditional form of Irish lament and sings grief related to emigration and grief caused by AIDS. Listen for the traditional cry of “ochón.”

“Nude” – Radiohead

Bringing in some movement now after our ‘set one’ of still listening. Feel the tilt of this waltz gently push you around while the vocals reach and spin.

“Without The Light” – Kelly Joe Phelps

Kelly brings in some sonic reverence here, reaching upward and swimming through memory. “I can see better without the light.” This relaxing into surrender here, perhaps even some praise for the grief in how this song is presented, is an important point in the process. We throw up our hands at the mystery of it all. We sit in awe of the many threads that connect to our heart from all we’ve lived through, from all those we have shared love with. This expression of love – our grief – is actually nourishment towards those living strands that connect us through worlds.

“Vuela Golondrina” – Coral Rojo

Morning light beams through this tune from Chilean vocal ensemble Coral Rojo. The lyrics here speak (again) of birds, both the swallow and the condor, of water, of revolving and renewing time, and the patterns and daily rituals of the natural world healing and waking us to new days. “Cry your sorrows while the mountain range shines as the day arrives.”

“Acid Rain” – Lorn

I’m including this dark ambient, industrial track from Milwaukee artist Lorn to honestly reflect the variety of tunes that do this work for me, personally. Here, bringing in the big guns of bass and synth grit to massage out angst and sorrow stored deep in the muscle. Sometimes you need to order size large.

“Surrender” – Rotana, Superposition

The tunes on this project from Palestinian/Saudi vocalist Rotana and duo Superposition are truly animated prayers and meditations. By that I mean, breathing life, bringing into life, and making alive old and new words. It takes a lot of experience and intention to keep that devotion in your music. Rotana sings codes of freedom.

“Song of Marriage” – Young girl in Huancavalica, Mountain Music of Peru, Vol. 1

I found this song very recently while listening through a track that shared five-second samples of all of the music on Voyager’s Golden Record (a project that served as a “message in a bottle” for extraterrestrial life led by Carl Sagan in the 1970s). It stuck out to me, even though it was a sweet young voice, I could tell it was some form of blues. Looking up more information about the track, I learned that it was actually lament. Across cultures, in addition to lamentation being used to accompany death, laments are sung quite often to accompany the journey crossing the threshold of entering marriage, as ritual protection in that liminal space, particularly for the bride leaving her family and entering a different life.

“Oh Aadam, sino essitus” – Anonymous, Heinvaker

This project from an Estonian vocal ensemble featuring folk hymns and runic songs was one I listened to a lot in the first summer of the pandemic. The sound is such a balm. A close friend once remarked that this music gave him such pride and hope in what humans are capable of. The actual singing of it, that we are capable of creating this resonance with each other, shows us that we hold such power to shape our world, that we can be positive citizens in the large environment. On our theme today, let this tune speak to the transformation that we lead ourselves on through the journey of grief. We are capable, and we are deeply belonging to this big web of creation.

Photo Credit: Harpe Star