The nominees for the 2026 GRAMMY Awards have been announced by the Recording Academy, looking ahead to “Music’s Biggest Night” on Sunday, February 1, 2026 at the Crypto.com Arena in Los Angeles, California. The primetime show will be broadcast live on CBS and will stream live and on demand on Paramount+.

Legends, icons, familiar names, and first-time nominees can all be found across the 95 GRAMMY categories that have been unveiled. In the Country & American Roots Music field, standouts include Tyler Childers (4 nominations), Lainey Wilson (3 nominations), Sierra Hull (4 nominations, including Best Instrumental Composition), Jesse Welles (4 nominations), and I’m With Her (3 nominations). Alison Krauss & Union Station, who released their first album in 14 years, Arcadia, earlier this year, have been nominated twice for 2026, bringing Krauss’ total number of nominations across her career to 46. Krauss is one of the most-nominated and most-awarded artists in GRAMMY history.

Unsurprisingly, one of those nominations for Krauss & Union Station finds Arcadia in the running for Best Bluegrass Album. The LP will compete with Carter & Cleveland by Jason Carter & Michael Cleveland, A Tip Toe High Wire by Sierra Hull, Outrun by the SteelDrivers, and Highway Prayers by Billy Strings for the Best Bluegrass Album gramophone. (This year, Best Bluegrass Album is Strings’ sole nomination.)

In country, for the first time Best Country Album has been split into two constituent categories, Best Contemporary Country Album and Best Traditional Country Album. Kelsea Ballerini, Tyler Childers, Eric Church, Jelly Roll, and Miranda Lambert will vie for Best Contemporary Country Album this year, while Charley Crockett, Margo Price, and Zach Top find themselves nominated for Best Traditional Country Album – with father-and-son Willie and Lukas Nelson nominated as well, pitted against each other for the very first time.

Outside of the Country & American Roots Music field, roots musicians are represented far and wide. Béla Fleck, Edmar Castañeda, and Antonio Sánchez’s BEATrio self-titled record is nominated for Best Contemporary Instrumental Album. Dan Auerbach is up for Producer of the Year (Non-Classical). Elton John and Brandi Carlile are nominated for Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album and Best Song Written For Visual Media. Plus, Sinners, the phenomenal and horrifying Ryan Coogler film steeped in various roots music traditions, has racked up five nominations across categories and fields.

It’s certainly an exciting roster of nominees for the 2026 GRAMMY Awards! Below, find the complete list of nominations from the Country & American Roots Music field, plus select categories featuring roots musicians, artists, and projects from across the various other GRAMMY fields and categories.

The 68th Annual GRAMMY Awards will take place on Sunday, February 1, 2026.

Country & American Roots Music

Best Country Solo Performance

“Nose On The Grindstone” – Tyler Childers

“Good News” – Shaboozey

“Bad As I Used To Be” – Chris Stapleton

“I Never Lie” – Zach Top

“Somewhere Over Laredo” – Lainey Wilson

Best Country Duo/Group Performance

“A Song To Sing” – Miranda Lambert, Chris Stapleton

“Trailblazer” – Reba McEntire, Miranda Lambert, Lainey Wilson

“Love Me Like You Used To Do” – Margo Price, Tyler Childers

“Amen” – Shaboozey, Jelly Roll

“Honky Tonk Hall Of Fame” – George Strait, Chris Stapleton

Best Country Song

“Bitin’ List” – Tyler Childers, songwriter. (Tyler Childers)

“Good News” – Michael Ross Pollack, Sam Elliot Roman, Jacob Torrey, songwriters. (Shaboozey)

“I Never Lie” – Carson Chamberlain, Tim Nichols, Zach Top, songwriters. (Zach Top)

“Somewhere Over Laredo” – Andy Albert, Trannie Anderson, Dallas Wilson, Lainey Wilson, songwriters. (Lainey Wilson)

“A Song To Sing” – Jenee Fleenor, Jesse Frasure, Miranda Lambert, Chris Stapleton, songwriters. (Miranda Lambert, Chris Stapleton)

Best Traditional Country Album

Dollar A Day – Charley Crockett

American Romance – Lukas Nelson

Oh What A Beautiful World – Willie Nelson

Hard Headed Woman – Margo Price

Ain’t In It For My Health – Zach Top

Best Contemporary Country Album

Patterns – Kelsea Ballerini

Snipe Hunter – Tyler Childers

Evangeline Vs. The Machine – Eric Church

Beautifully Broken – Jelly Roll

Postcards From Texas – Miranda Lambert

Best American Roots Performance

“LONELY AVENUE” – Jon Batiste, Featuring Randy Newman

“Ancient Light” – I’m With Her

“Crimson And Clay” – Jason Isbell

“Richmond On The James” – Alison Krauss & Union Station

“Beautiful Strangers” – Mavis Staples

Best Americana Performance

“Boom” – Sierra Hull

“Poison In My Well” – Maggie Rose, Grace Potter

“Godspeed” – Mavis Staples

“That’s Gonna Leave A Mark” – Molly Tuttle

“Horses” – Jesse Welles

Best American Roots Song

“Ancient Light” – Sarah Jarosz, Aoife O’Donovan, Sara Watkins, songwriters. (I’m With Her)

“BIG MONEY” – Jon Batiste, Mike Elizondo, Steve McEwan, songwriters. (Jon Batiste)

“Foxes In The Snow” – Jason Isbell, songwriter. (Jason Isbell)

“Middle” – Jesse Welles, songwriter. (Jesse Welles)

“Spitfire” – Sierra Hull, songwriter. (Sierra Hull)

Best Americana Album

BIG MONEY – Jon Batiste

Bloom – Larkin Poe

Last Leaf On The Tree – Willie Nelson

So Long Little Miss Sunshine – Molly Tuttle

Middle – Jesse Welles

Best Bluegrass Album

Carter & Cleveland – Michael Cleveland & Jason Carter

A Tip Toe High Wire – Sierra Hull

Arcadia – Alison Krauss & Union Station

Outrun – The SteelDrivers

Highway Prayers – Billy Strings

Best Traditional Blues Album

Ain’t Done With The Blues – Buddy Guy

Room On The Porch – Taj Mahal & Keb’ Mo’

One Hour Mama: The Blues Of Victoria Spivey – Maria Muldaur

Look Out Highway – Charlie Musselwhite

Young Fashioned Ways – Kenny Wayne Shepherd & Bobby Rush

Best Contemporary Blues Album

Breakthrough – Joe Bonamassa

Paper Doll – Samantha Fish

A Tribute To LJK – Eric Gales

Preacher Kids – Robert Randolph

Family – Southern Avenue

Best Folk Album

What Did The Blackbird Say To The Crow – Rhiannon Giddens & Justin Robinson

Crown Of Roses – Patty Griffin

Wild And Clear And Blue – I’m With Her

Foxes In The Snow – Jason Isbell

Under The Powerlines (April 24 – September 24) – Jesse Welles

Best Regional Roots Music Album

Live At Vaughan’s – Corey Henry & The Treme Funktet

For Fat Man – Preservation Brass & Preservation Hall Jazz Band

Church Of New Orleans – Kyle Roussel

Second Line Sunday – Trombone Shorty And New Breed Brass Band

A Tribute To The King Of Zydeco – Various Artists

General Field

Producer of the Year (Non-Classical)

Dan Auerbach

Cirkut

Dijon

Blake Mills

Sounwave

Jazz, Traditional Pop, Contemporary Instrumental & Musical Theater

Best Jazz Performance

“Noble Rise” – Lakecia Benjamin, Featuring Immanuel Wilkins & Mark Whitfield

“Windows – Live” – Chick Corea, Christian McBride & Brian Blade

“Peace Of Mind / Dreams Come True” – Samara Joy

“Four” – Michael Mayo

“All Stars Lead To You – Live” – Nicole Zuraitis, Dan Pugach, Tom Scott, Idan Morim, Keyon Harrold & Rachel Eckroth

Best Jazz Instrumental Album

Trilogy 3 (Live) – Chick Corea, Christian McBride & Brian Blade

Southern Nights – Sullivan Fortner, Featuring Peter Washington & Marcus Gilmore

Belonging – Branford Marsalis Quartet

Spirit Fall – John Patitucci, Featuring Chris Potter & Brian Blade

Fasten Up – Yellowjackets

Best Alternative Jazz Album

honey from a winter stone – Ambrose Akinmusire

Keys To The City Volume One – Robert Glasper

Ride into the Sun – Brad Mehldau

LIVE-ACTION – Nate Smith

Blues Blood – Immanuel Wilkins

Best Traditional Pop Vocal Album

Wintersongs – Laila Biali

The Gift Of Love – Jennifer Hudson

Who Believes In Angels? – Elton John & Brandi Carlile

Harlequin – Lady Gaga

A Matter Of Time – Laufey

The Secret Of Life: Partners, Volume 2 – Barbra Streisand

Best Contemporary Instrumental Album

Brightside – ARKAI

Ones & Twos – Gerald Clayton

BEATrio – Béla Fleck, Edmar Castañeda, Antonio Sánchez

Just Us – Bob James & Dave Koz

Shayan – Charu Suri

Gospel & Contemporary Christian Music

Best Roots Gospel Album

I Will Not Be Moved (Live) – The Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir

Then Came The Morning – Gaither Vocal Band

Praise & Worship: More Than A Hollow Hallelujah – The Isaacs

Good Answers – Karen Peck & New River

Back To My Roots – Candi Staton

Latin, Global, Reggae & New Age, Ambient, or Chant

Best Música Mexicana Album (Including Tejano)

MALA MÍA – Fuerza Regida, Grupo Frontera

Y Lo Que Viene – Grupo Frontera

Sin Rodeos – Paola Jara

Palabra De To’s (Seca) – Carín León

Bobby Pulido & Friends Una Tuya Y Una Mía – Por La Puerta Grande (En Vivo) – Bobby Pulido

Best Global Music Performance

“EoO” – Bad Bunny

“Cantando en el Camino” – Ciro Hurtado

“JERUSALEMA” – Angélique Kidjo

“Inmigrante Y Que?” – Yeisy Rojas

“Shrini’s Dream (Live)” – Shakti

“Daybreak” – Anoushka Shankar, Featuring Alam Khan, Sarathy Korwar

Children’s, Comedy, Audio Books, Visual Media & Music Video/Film

Best Song Written For Visual Media

“As Alive As You Need Me To Be” [From TRON: Ares] – Trent Reznor & Atticus Ross, songwriters. (Nine Inch Nails)

“Golden” [From KPop Demon Hunters] – EJAE & Mark Sonnenblick, songwriters. (HUNTR/X: EJAE, Audrey Nuna, REI AMI)

“I Lied to You” [From Sinners] – Ludwig Göransson & Raphael Saadiq, songwriters. (Miles Caton)

“Never Too Late” [From Elton John: Never Too Late] – Brandi Carlile, Elton John, Bernie Taupin & Andrew Watt, songwriters. (Elton John, Brandi Carlile)

“Pale, Pale Moon” [From Sinners] – Ludwig Göransson & Brittany Howard, songwriters. (Jayme Lawson)

“Sinners” [From Sinners] – Leonard Denisenko, Rodarius Green, Travis Harrington, Tarkan Kozluklu, Kyris Mingo & Darius

Povilinus, songwriters. (Rod Wave)

Production, Engineering, Composition & Arrangement

Best Instrumental Composition

“First Snow” – Remy Le Boeuf, composer. (Nordkraft Big Band, Remy Le Boeuf & Danielle Wertz)

“Live Life This Day: Movement I” – Miho Hazama, composer. (Miho Hazama, Danish Radio Big Band & Danish National Symphony Orchestra)

“Lord, That’s A Long Way” – Sierra Hull, composer. (Sierra Hull)

“Opening” – Zain Effendi, composer. (Zain Effendi)

“Train To Emerald City” – John Powell & Stephen Schwartz, composers (John Powell & Stephen Schwartz)

“Why You Here / Before The Sun Went Down” – Ludwig Göransson, composer. (Ludwig Göransson, Featuring Miles Caton)

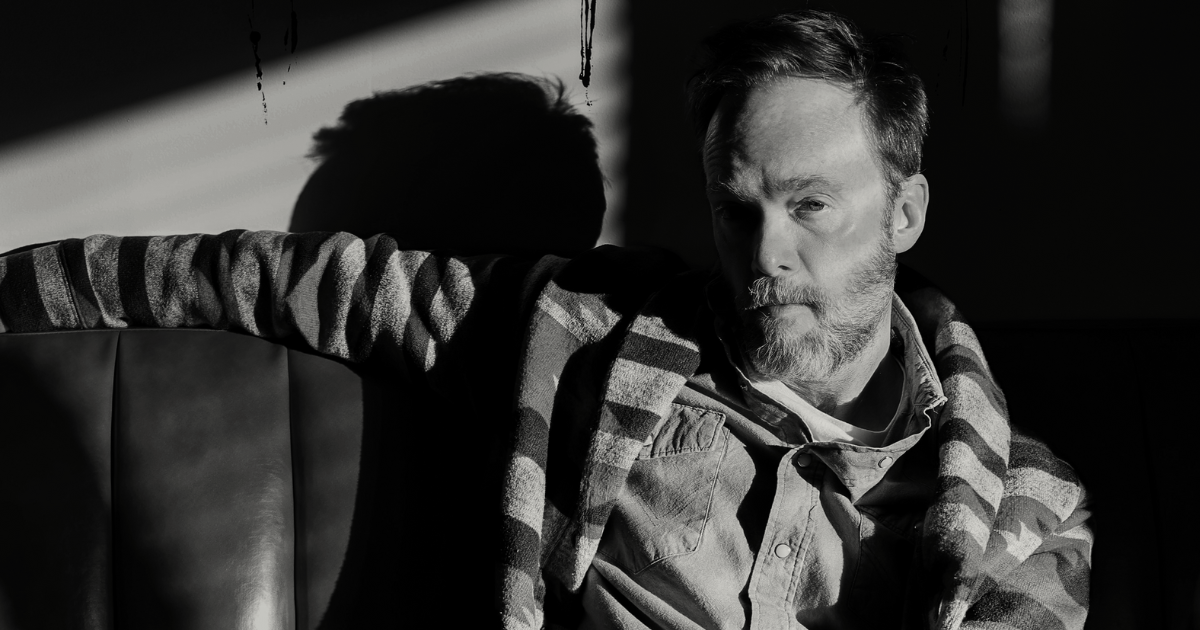

Photo Credit: Tyler Childers by Sam Waxman; Sierra Hull courtesy of the artist.