An entire year of Good Country has blown by! Our new email newsletter and brand has gone so much further and has reached so many more country fans than we ever imagined when we launched in January. The concept is simple: there’s plenty of Good Country out there, and we want to highlight all of it.

As we look back at 2024 and the first twelve months of GC, we asked our pantheon of contributors to collect their favorite country releases from the calendar year. We did not determine for our writers what qualifies as country – or what does not. It’s important for GC to facilitate a country space that attempts to revert this music back to its earliest days, before genres and formats split up the many subgenres and downstream styles of country into various, distinct buckets and boxes.

One of the things most clear to us after a year of GC is that our central premise is certainly true. There’s endless Good Country out there – especially when you’re open to as many styles and aesthetics, influences and entry points as possible. From mainstream, radio country to red dirt, from bluegrass to Southern rock, from old-time to down home blues. Good Country is more than a genre, it’s more than a simplistic pitch to “save” this music we love. Good Country is a place, it’s an idea, a way of viewing the world – musical and otherwise. And we’re so grateful to all of you for joining us in Good Country.

Scroll for the playlist of our favorite 2024 Good Country below!

Kassi Ashton, Made From the Dirt

Kassi Ashton spent the better part of a decade honing her craft and trying out various promotional singles to gain traction. It wasn’t until “Called Crazy,” her third official single, that she hit the Top 40 on country radio. The minor success primed listeners for her long-awaited debut record, Made From the Dirt, a beautifully produced and raucous set blending the best parts of mainstream country. Ashton runs on high-octane energy – with her thick twang packing a punch on each loose-lipped syllable. From the propulsive “Son of a Gun” to the slow rollin’ “‘Til the Lights Go Out,” her debut radiates from the inside out and carries with it cross-generational appeal. – Bee Delores

Kaitlin Butts, Roadrunner!

Set to the timeless musical Oklahoma!, Kaitlin Butts’ Roadrunner! is as much a modern retelling of the epic tale as it is a road map of her own exploits thus far. On the 17-track project she shines on soft, nurturing ballads like the Vince Gill-featured duet “Come Rest Your Head (On My Pillow),” “People Will Say We’re In Love” (starring partner and Flatland Cavalry lead Cleto Cordero — the only song pulled straight from the musical), and “Elsa,” a tune about a woman she met while playing nursing home gigs back in the day.

But, she also revels in its more chaotic moments as well, as is the case with “You Ain’t Gotta Die (To Be Dead to Me)” and a Kesha cover, “Hunt You Down.” Through these vignettes Butts not only shows that the near-century-old musical remains as impactful as ever, but that her music has the power to do the same. – Matt Wickstrom

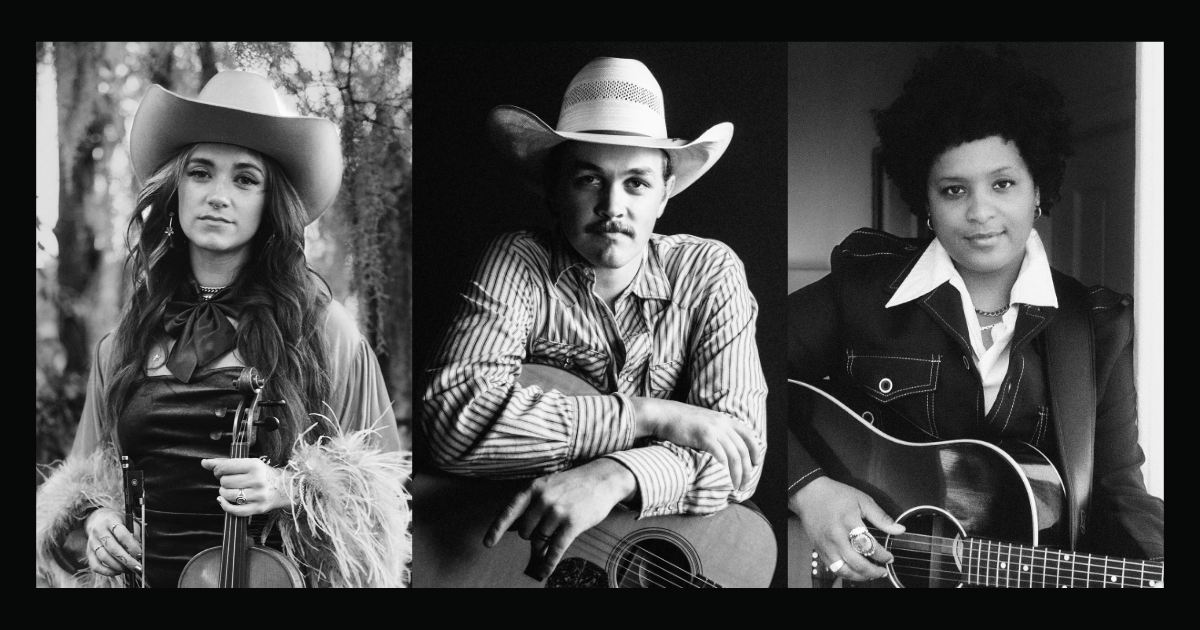

Denitia, Sunset Drive

Okay, I am shook that Denitia has not been studying, writing, and recording country music for all her life. Formerly an R&B artist (just go on and check out her wicked 2018 album, Touch of the Sky), Denitia’s on her second country record and it sounds exactly how I’d want a country record to sound. Admittedly, I am not a huge country fan (except I know all the words to every song on ‘90s country radio stations), but Sunset Drive rings my bell from top to bottom. Her clear and cool ‘90s-inspired, indie voice and her flawless writing are on full display with songs like “Back to You” and “Gettin’ Over.” The flow of the writing and instrumentation are seamless. No notes, Denitia! Hope they wise up and get you on the radio. – Cindy Howes

Sierra Ferrell, Trail of Flowers

In this instant classic, Trail of Flowers firmly establishes Sierra Ferrell as the voice of a generation. Her indelible songwriting delivered by her uncommon vocals will be revered indefinitely. I’ve had the honor of seeing her perform twice (well, maybe more like once and a half) since the album’s release, each time surrounded by an audience brought to their knees by her sheer, unadulterated power. At DelFest, hundreds of us sheltered for nearly an hour in the grandstand after an untimely lightning storm struck following the opening chords of “Jeremiah.” We rushed back to the stage in troves as soon as the skies began to clear, only to be utterly heartbroken upon learning that her set would not continue. Sierra’s performances are unspeakably transformative – her authenticity and eminence evoke the divine. Trail of Flowers offers us a precious keepsake, a textured collection of harvested treasures both earthly and ethereal. – Oriana Mack

Sam Gleaves, Honest

Maybe country music could leave behind its ongoing debate around “authenticity” forever, because the best country doesn’t need to be “authentic,” it just needs to be honest.

Sam Gleaves is an Appalachian singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, educator, and community builder whose every note, sung or plucked, is as truthful and stalwart as the mountains he calls home. His new album, Honest, combines old-time, honky tonkin’ country, bluegrass, and mountain music in a charming, down-to-earth package that’s never ambitious or try-hard. At the same time, this is one of the best country albums of the year and then some, with impeccable, tear-jerker tracks like “Beautiful” and hilarious, sexy romps like “Queer Cowboy.” There’s no performance of traditional authenticity signifiers here; Gleaves’ most radical act is allowing us to perceive him wholly, through his music. That’s all too rare in mainstream country, but a longstanding legacy that’s alive and well on the genre’s fringes. – Justin Hiltner

Mickey Guyton, This Is Who I’ve Always Been

Although she’s long considered herself an “outlaw,” Mickey Guyton has steadily moved up the country music ladder. She’s ultimately emerged as a consistent example of individuality and creativity. She’s battled since signing her first deal in 2011, refusing to accept the notion that being Black and outspoken placed limits on either outreach or popularity. She’s steadily smashed barriers, most notably being the first Black woman to be nominated in the Best Country Song GRAMMY category, and the first to both perform at and later co-host the Academy of Country Music Awards.

But she’s now also realizing her greatest musical achievements. Guyton’s latest LP, This Is Who I’ve Always Been, is a marvelous declaration of her country roots and legacy, a recorded statement that says everything without being overtly political in lyrical tone and presentation. There are 12 joyous, rousing tracks that spotlight her writing skills alongside Tyler Hubbard and Corey Crowder. It’s only fitting that she’s joined by Kane Brown on the stirring “Nothing Compares to You.” It’s a powerhouse tune co-written by Hubbard, Bebe Rexha, and Jordan Schmidt that is arguably the LP’s definitive performance. Guyton is now a Nashville resident, and this album celebrates her triumph as a true example of country’s diversity and inclusion. – Ron Wynn

Stephanie Lambring, Hypocrite

We should all be talking about Stephanie Lambring more. Like, a lot more. On her sophomore album, Hypocrite, Lambring continues her all-killer-no-filler critiques of patriarchy and oppression. The album opens with the ominous pop of “Cover Girl” before delving into the shattering vulnerability of “Good Mother.” Lambring has had her share of bitter experience in the Nashville machine and sharing those stories of superficial “authenticity” has proved to be the best thing she could have done – liberating for her, yes, but also offering the rest of us a portal to examine our ingrained biases and, hopefully, to break free of them. Hypocrite is not an easy listen – if you are a human being, you will squirm at least once listening to these lyrics – but it’s essential. – Rachel Cholst

Cindy Lee, Diamond Jubilee

Cindy Lee is the non-binary alter-ego of Patrick Flegel, reclusive former leader of Canadian post-punk band Women – and you could say Flegel made some curious decisions about how to put this music out into the world. Instead of the usual streaming sites, Diamond Jubilee lives primarily on YouTube as a two-hour-plus video of all 32 songs as a single track, no breaks. But don’t let that scare you. Diamond Jubilee is spectral late-night soundtrack music to a movie that hasn’t been made yet. You sure can picture it, though. The sonics are proudly low-fidelity, yet the gauzy arrangements are precise (and Flegel is one hell of an evocative less-is-more guitarist). Imagine Brian Wilson conducting teenage symphonies to the afterlife, and you’re in the ballpark. An amazing collection of music, deep as it is broad. – David Menconi

Adrianne Lenker, Bright Future

Indie-country-folk enigma Adrianne Lenker didn’t use a single piece of digital equipment while recording her seventh full-length solo album, Bright Future. Instead, she and five friends hunkered down at a studio that’s only been described publicly as “in the woods” somewhere in New England. They recorded an intimate, intuitive album using a process known as AAA. (That’s analog recording, analog mixing, and analog mastering.)

Despite its decidedly anachronistic engineering, Bright Future is one of the most unique and powerful American folk releases of 2024. It’s even been nominated for a GRAMMY for Best Folk Album, marking Lenker’s first GRAMMY nomination as a solo artist. Listening to the album feels like sitting in a small, warm room with Lenker and her collaborators, with every breath and every shifting movement still audible on the tape. For me, getting releases like this that feel so undeniably rooted in the real, tangible world, really does make the future seem a bit more bright – a small form of resistance against the forced digitization of our lives. – Dana Yewbank

Pete Mancini, “American Equator”

Pete Mancini has been carving a path for himself through the country music landscape since the release of his debut solo album in 2017. Coincidentally, the title of his newest single, “American Equator,” is inspired by the idea of a literal divide carved into the U.S. landscape. Mancini can be playful, imaginative, and solemn with his writing and “American Equator” showcases these qualities sewn together. Much like the faders mentioned in the song’s chorus, Mancini knows when and how to apply blunt honesty for several true-to-life references and when to present the ugliness of the song’s settings through a no less candid but much more palatable metaphor. Even if heavy narratives aren’t what you’re after, the steady groove, power-pop style guitar tone, and hopeful arc of the chord progression make “American Equator” a tune that’s easy to turn up and enjoy – especially on long highway road trips. – Kira Grunenberg

John Moreland, Visitor

For a slice of the country music-listening public, April 5, 2024 had December 13, 2013 energy. In fact, were Beyoncé not the Beyoncé of country music, I might say that John Moreland is the Beyoncé of country music. Both are undeniable stars and underrated producers. Visitor is a beautiful album that reveals brilliant new details with each listen. I sometimes feel fragile when the drums kick in on “Blue Dream Carolina,” but by the end of the track I always feel better. I am so happy that this songwriter’s songwriter keeps growing his audience. I am not entirely sure what country music is. I wish more of it sounded like a John Moreland record. – Lizzie No

Lizzie No, Halfsies

This was the year when Lizzie No seemed to fully embody their inner country crooner. No welcomed 2024 with the release of Halfsies in January on Thirty Tigers. Its songs tell a story of being female in an America that expects more of its women the more the melanin in their skin. When No sang in the title track about leaving her “sandals in a cab” and finding “a snakeskin in the grass,” she was talking about pain and loss and transformation. About the performative nature of identity. When Loretta Lynn sang “You’re lookin’ at country,” she was talking about what people are looking for as much as what they actually see. If Lynn has a legatee in today’s country circles, it just might be Lizzie No. – Kim Ruehl

The Red Clay Strays, Made by These Moments and Live at the Ryman

Bursting out of their native Mobile, Alabama, The Red Clay Strays emerged as the hottest live act of 2024. A snarling blend of Americana, rock, and alt-country tones, the group went from selling 40 tickets a gig to 4,000 in less than 18 months – an incredible feat by any measure, and one immediately justified by the “you had to be there” stage presence of lead singer Brandon Coleman and company.

Rolling into this summer, the Strays offered up their sophomore album, Made by These Moments, to wide acclaim from audiences and critics alike. But, it was the recently-released Live at the Ryman that truly showcases the intricate depth of sonic abilities and fire-and-brimstone vocal prowess at the heart of the outfit. The biggest takeaway? There’s no ceiling to the size and scope of where the Strays can take their music – in the studio or onto the stage. What remains is pure passion and guided purpose for their craft, this platform for compassion they hold with deep respect. – Garret K. Woodward

Zach Top, Cold Beer & Country Music

Rest easy, for country has been saved! But no, because Zach Top himself doesn’t even believe that the genre needs to be rescued. Even so, this young bluegrass-raised artist, who seemingly catapulted overnight into retro, nostalgic country stardom, is doing his utmost to keep the realest kinds of ‘90s and throwback country alive and contemporary. With the mustache and Wrangler jeans to prove it. Watching as his audience has ballooned over the last year demonstrates that Top is certainly not alone in his love for this kind of archetypical country. “I Never Lie” is probably the most impactful and far-reaching single from the genre of the year, as recognizable and requested on Lower Broadway as in the halls of SPBGMA (the Society for the Preservation of Bluegrass Music in America). Top brings so many circles of the country music Venn diagram together, organically, and we are all better for it. I hope I stay embedded on Zach TopTok forever. – Justin Hiltner

Twisters Soundtrack

Twisters is not a great movie, though it would have been better if they let Glen Powell fuck. Or if they let the weirdness that David Corenswet displayed in Pearl show up here. It would have been a more politically relevant movie if the director didn’t refuse to talk about climate change – which is why all of the chaotic weather is happening in Oklahoma.

Its soundtrack, though, is genuinely great. Part of the reason why is how carefully it was marketed – to work through the ongoing genre battles in country, to acknowledge the nostalgia of the original 1990s film, and to think about what country might mean more broadly. Ignoring climate change might be part of the film’s faltering, foisting the bland hegemony of Powell is also part of it, but the album is more disruptive. And more beautiful than it has any right to be. It almost reaches gender parity, it has half-a-dozen Black performers, there are legacy acts and up-and-comers. Listening to the Twisters soundtrack this year made me yearn for a counterfactual country radio. – Steacy Easton

Rhonda Vincent, Destinations and Fun Places

I’m a firm believer that bluegrass sits pretty under the umbrella of “country music.” If you’re a country music lover and are looking to expand your horizons, let my 2024 Good Country selection nudge you towards some ‘grass. You’ll thank me later.

This year, Rhonda Vincent released her highly-anticipated album, Destinations and Fun Places, and it’s soooo Bluegrass Barbie-coded. From her stunning hot pink dress on the cover to her top-notch covers like “9 to 5” and “Please Mr Please,” Rhonda proves she’s still the queen. With featured artists like Dolly Parton, Trisha Yearwood, Cody Johnson, and Alison Krauss, any country music fan would have plenty of familiar voices to enjoy. This record also showcases Rhonda’s musical range, with sweet songs like “I Miss Missouri” to bluegrass ragers like “Rocky Top.” From “Margaritaville” to “The City of New Orleans,” Rhonda Vincent is truly an American treasure. All hail the queen! – Bluegrass Barbie

Need more Good Country? Sign up on Substack to receive our monthly email newsletter with endless country, Americana, and more direct to your inbox.

Photo Credit: Sierra Ferrell by Bobbi Rich; Zach Top courtesy of the artist; Denitia by Chase Denton.