Bob Warford remembers a lot about the vibrant Southern California bluegrass and old-timey scene of the 1960s. But he doesn’t remember exactly how he came to be a member of what proved to be the final lineup of the Kentucky Colonels, the near-mythic group anchored by brothers Roland White on mandolin, Eric White Jr. on bass and, at times, guitar magician Clarence White.

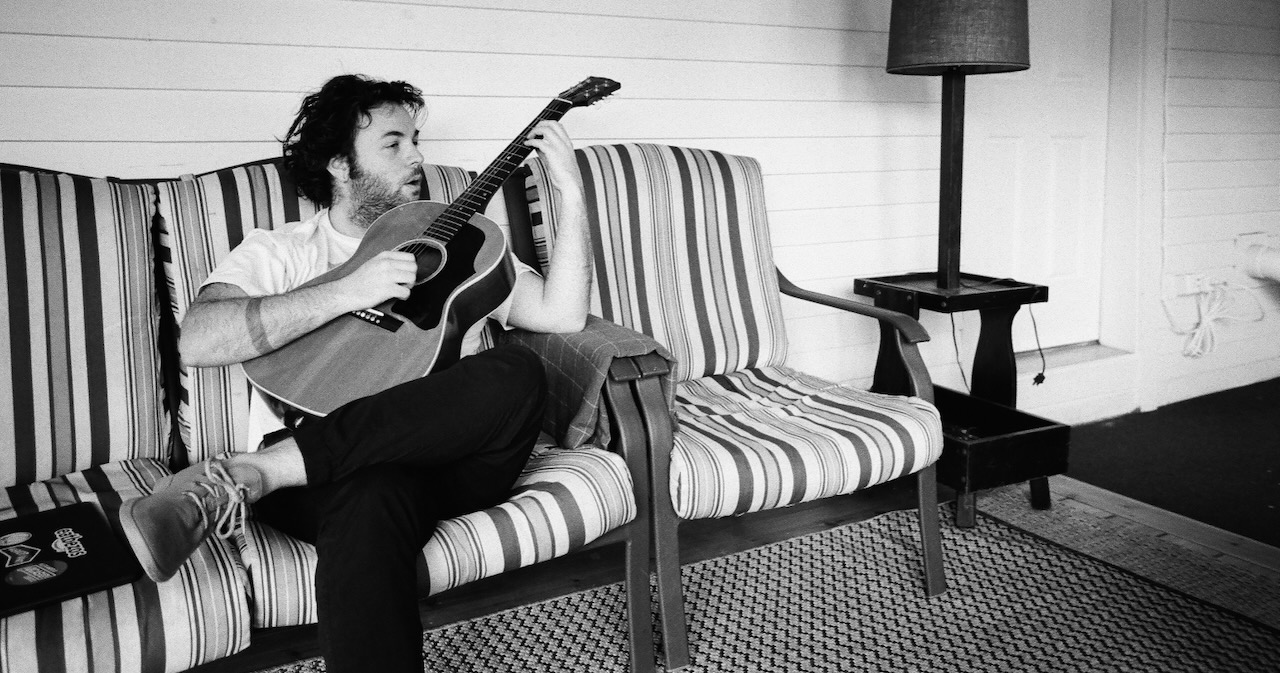

“My life was getting complicated at that time,” Warford, a banjo player, recalls. “I knew Clarence slightly. Roland slightly. I knew Eric. Maybe it was Eric who suggested me for it.”

He had grown up in the college town of Claremont, about half an hour east of Los Angeles, where he fell into bands — the Reorganized Dry City Players and the Mad Mountain Ramblers among them — with such future notables as David Lindley and Chris Darrow. After starting college further east at the University of California Riverside, he was in a band that played festivals and on the popular “Cal’s Corral” TV show (hosted by flashy Western-fashioned car dealer, Cal Worthington), appearing on the latter alongside the Gosdin Brothers, the Hillmen (featuring future Byrds star Chris Hillman) and others.

In any case, at the end of ’66 or beginning of ’67, in the home stretch of his undergraduate work and with plans for grad school on his way to becoming an attorney, Warford was asked to join the Colonels for a series of gigs at the famed Ash Grove club in Hollywood over the course of a few months. And in that February, in the midst of the Ash Grove run, the band was recruited to go in the studio for sessions to be featured on the pilot of a radio show titled “American Music Time,” hosted by and featuring married couple Dave and Lu Spencer and with crowd sounds added to give the impression that it was done in front of an audience.

It seems to have aired that March, though Warford can’t confirm that. It was, however, released on an album in the late 1970s — without the Spencers’ parts or the crowd noise — with the title 1966. On June 30 of this year it was reissued by label Sundazed and doubled in length with previously unreleased recordings of the Country Boys, the pre-Colonels band the White brothers had in the late ’50s and early ’60s.

“These were not done with any high-tech situation,” Warford recalls of the two (or maybe three) sessions held for the radio show. “Everything was played live. We didn’t do a large number of songs.”

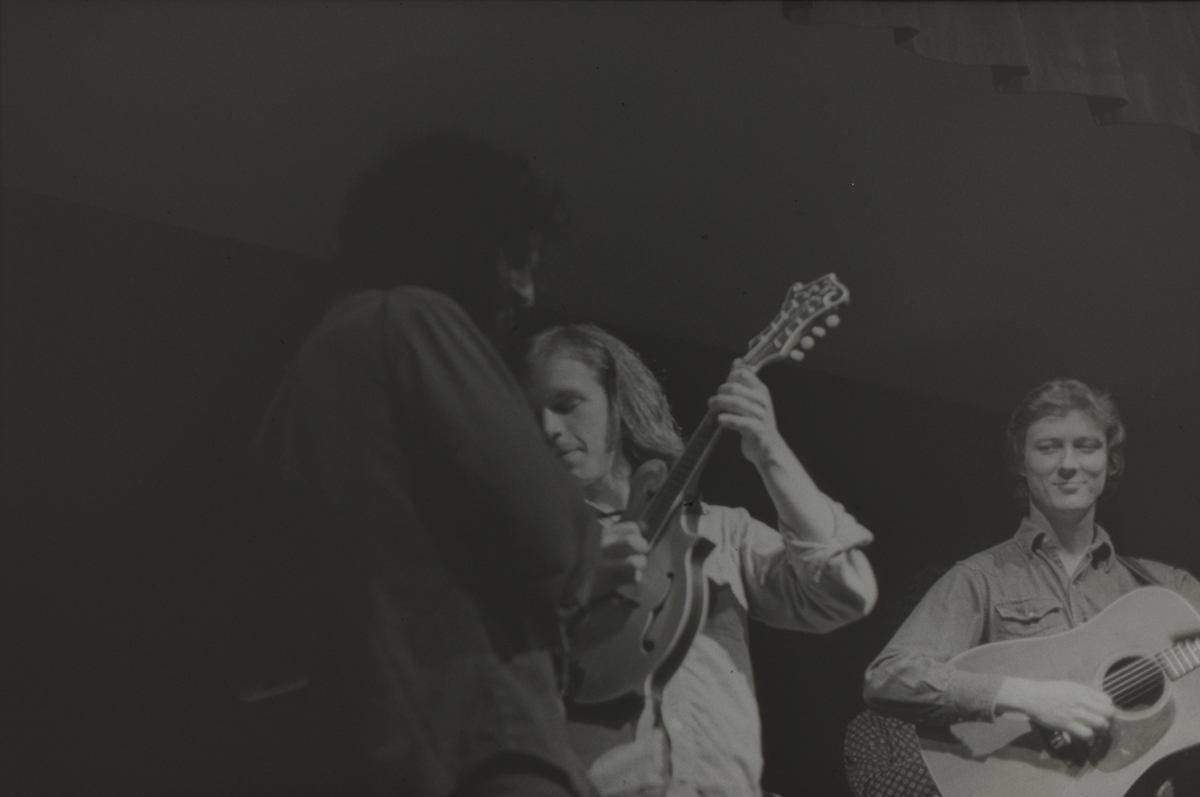

There are some bluegrass regulars (“Soldier’s Joy,” in short versions bookending the original release, Earl Scruggs’ “Earl’s Breakdown,” two Osborne Brothers tunes), some adaptations from country (Merle Haggard’s “The Fugitive”) and such. The performances are strong and lively, especially so considering that this was a reconstituted lineup of the band which had not played together a lot. In fact, before this run of gigs, the last official gig had been in October, 1965. Three of the five members were now new. Roland White was still there, and Eric was back, too, after having split from the ensemble some years before. Founding dobro player Leroy (Mack) McNees and banjoist Billy Ray Latham had moved on, as was ace fiddler Scotty Stoneman, who had played with the band in ’65.

“One thing this shows is that with or without Clarence, the Colonels was a good bluegrass band,” says folk music journalist and historian Jon Hartley Fox, who wrote the liner notes for the new 1966 release. “It’s sort of looked back on now maybe as the vehicle for Clarence. But they were a really good band in their own right. I think Roland White has historically been undervalued. Roland was a really good band leader. When it’s just Roland and Eric from the original band it’s still got the spirit and the same feel. The band was way more than Clarence and four other guys.”

As for Clarence, he’d begun his shift to a focus on electric guitar, picking up some major session work, which would lead to him playing on the Byrds’ country landmark Sweetheart of the Rodeo album and then later joining the band. But at that point, he was around some of the time, too. The band Warford joined now was filled out by fellow newcomers Dennis Morris on guitar and Bobby Crane on fiddle — though Morris’ last name might have been Morse and Crane’s first name may have been Jimmy. There’s a lot of uncertainty around this time, not least the status of the band itself, which was fine by Warford.

“I was still in college and was going to start grad school,” he says from his home in Riverside, where he settled into a successful law career. “For me, I wasn’t looking at anything long-term. I was thinking, ‘This is fun and these guys are really good players and we can do this while we do it.’ I didn’t have a view that it was about to end or that it could continue.”

As it turned out, it was about to end. The radio sessions would prove to be the last official recordings by the band. It also, in some ways, captures the last glimmer of that vibrant Southern California roots-music scene.

“If people think it’s tough to make a living playing bluegrass now, which it is, in 1967, especially in California, it was impossible,” says Fox. “If you look around the rest of the country, it was lean times for bluegrass.” Still, the Colonels had earned status.

“Even without Clarence in the band, they would’ve been the leading bluegrass band in California,” Fox says, crediting Roland White for keeping the Colonels alive as a band. “And in the national consciousness they were still one of the biggest things going. They really showed a kind of drive and ambition that a lot of people admired.”

But as time went on, that meant less and less — big fish, shrinking pond. Even at its peak a few years earlier, the scene in the area was not a way for musicians to get big paydays. But once the Beatles arrived and Dylan had gone electric, it was a different world. Locally, nothing captured the change more than Chris Hillman turning in his mandolin for an electric bass and co-founding the Byrds. Bluegrass just didn’t have much of a draw.

In 1961, the band, still known as the Country Boys, had what could have been a big break when it was hired to appear twice on The Andy Griffith Show. Unfortunately, it turned out to be an opportunity that fizzled. The producers wanted to have them back, “But the family moved and they couldn’t find them,” Fox says. “So they put an ad in the paper.”

And answering the ad was, yes, the Dillards, who auditioned and were hired, playing members of the mountain family the Darlings, ultimately performing 13 songs over the course of six episodes from 1963 to 1966 and gaining a national profile.

“In retrospect, I think the Dillards were much better suited to that show,” Fox says, citing again the Dillards’ bigger flair for showmanship. “The Colonels never had a show really,” he says. “They got up and played music.”

“The Dillards were such a mowing-down machine,” says Grammy Award-nominated reissue producer and annotator Mary Katherine Aldin, who worked at the Ash Grove starting in 1960. Through that latter role, she worked closely with the Colonels and later won the 1991 NAIRD Indie Award for producing and annotating the collection The Kentucky Colonels, Long Journey Home and wrote the liner notes for The New Kentucky Colonels Live in Holland 1973. Getting festival bookings became increasingly difficult, she says.

“It was, ‘We already have a bluegrass band, don’t need more,’” she says of the frustrations, and of course the one they already had was the Dillards, more often than not.

An exception was the Newport Folk Festival, and the Colonels did play there in 1964. But any momentum from that appearance was hard to sustain. By the time Warford joined, options had become fewer and fewer, not just on the festival level but on the local circuit that had been at least a steady, if unglamorous, platform.

“Now that I think about it, other than the Ash Grove, which was always a venue for folk and blues and old-timey stuff, there used to be pizza parlors and stuff with bluegrass bands on the weekends,” Warford says. “I don’t recall any still around then.”

The Ash Grove did remain the prime location for the music, regardless, with such future stars as Ry Cooder, Jackson Browne, and Taj Mahal citing it as a place where they could meet and learn from their heroes. The Colonels’ and the club’s legacies were very much entwined, right from the start. The White brothers, with their family having moved from Maine to Burbank on the Eastern part of L.A.’s San Fernando Valley, started playing the Ash Grove shortly after it opened on Melrose Ave. in Hollywood in 1958 with folk and blues fanatic Ed Pearl at the helm.

A year before that, the band was known as the Three Little Country Boys, with Roland on mandolin, Eric on banjo, Clarence — barely in his teens — on guitar, and sister Joanne sometimes on bass. Soon they won a radio station competition and changed the name simply to the Country Boys, with Eric taking over the bass and banjoist Billy Ray Latham and dobro player Leroy “Mack” McNees added to fill out the lineup, though that would change, too, when Eric left and Roger Bush was recruited.

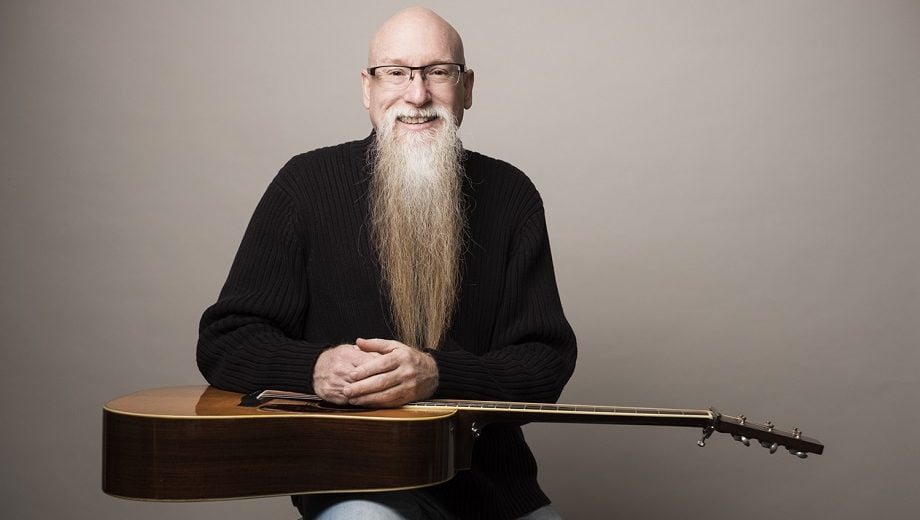

“It was 1959 when I joined them,” Bush says now. “Got a phone call one day from Leroy Mack, said he was playing with Billy Ray and Roland, and the brother Eric played bass fiddle. That is it. The whole little band. They were working, played a radio show and TV show with the car salesman who had live music. Playing at the Ash Grove, had a deal with the owner, if he could call us when somebody didn’t show up and we could come fill some time, we would have the full run of the building during the day to rehearse with the full sound system. Then [we played] every Saturday morning.”

The family dynamic had its tensions, it seems, and the breaking point that led to Bush’s entry was sartorial.

“Roland tried to put everyone in white bucks,” Bush says. “They got up one morning at home, the White family, there was a note hung on the bass fiddle from Eric that said, ‘I quit.’ They opened the back door and there was his white bucks that had been on fire. Leroy called me up, I said, ‘You know, I’ve never played the bass fiddle, but wouldn’t mind giving it a whirl. We did a show, a school or college. That was my first show. I hadn’t gotten together with them but one time. We did the first song, nobody stepped to the microphone. They looked at me and said, ‘Go talk to them.’ That was the beginning of me being the talker in the band. They didn’t call me Flutter-Lip for nothing. I was always the talker.”

This is the time period represented in the album’s expanded tracks. The recordings, raw but lively, show an exuberant, youthful ensemble with vibrant performances of mostly traditional material (“Head Over Heels In Love With You,” “Shady Grove,” “I’ll Go Steppin’ Too,” “Flint Hill Special”) and a modicum of hokum to boot (“Polka on the Banjo,” “Shuckin’ the Corn,” “Mad Banjo”).

Fox stresses that these early recordings were before Clarence broke out as a star attraction.

“He wasn’t playing lead yet,” he says. “He didn’t really start playing any lead until Roland went into the army in 1962.”

For the older brother, that produced something of a crossroads-level shock on return. “Roland talked about how surprised he was coming home from Germany, and here was Clarence playing fiddle tunes [on guitar],” Fox says. “But his rhythm playing on the old stuff is great.”

It was around this time that they recorded an album and, at the urging of mentor Joe Maphis, took on the name the Kentucky Colonels, regardless of the geographical disconnect. The album, The New Sound of Bluegrass America, came out in 1963. Clarence’s flat-picking shined, making him, for many, the band’s star attraction – even more so with the instrumental album, Appalachian Swing!, with fiddler Bobby Slone added to the lineup, released by prominent LA jazz, world, and folk label World Pacific Records.

Katherine Aldin witnessed this transformation and Clarence’s emerging stardom up close at the Ash Grove: “One thing about them – Clarence, even in those days, overshadowed everyone in the band,” she says. “So you’d get a whole flock of people who would come in and sit at the foot of the stage. There was a long metal bar with single seats in a V shape around the stage. The Clarence fanatics would get there early and sit there and glue their eyes on Clarence’s hands for 45 minutes and when they were done, just go away. He would suck the air out of the room. The other guys were really good too and wonderful human beings. But Clarence was head and shoulders above the rest of the world.”

His presence went beyond his skills. “Clarence would sit in the front room — there was a concert room and front room,” Aldin explains. “And he would sit in the front room between sets and any kid who came up to him, he would show them anything. And there were a lot of kids. He would show them a lick, or let them play his guitar, or if they brought a guitar he would play with them.”

But momentum was hard to sustain. Mack left the group in ’64 (he’s only on a few of the Swing! tracks) to work in his dad’s construction business, then Slone left and fiddle star Stoneman came in and for all intents by the end of ’65 the band was inactive until that short, final ’67 stretch.

“I think the band just kinda ran out of work to do,” Bush says.

The members went on to other jobs, in and out of music. Clarence famously became an in-demand session player with his switch to electric guitar and supported by James Burton, one of the top guitarists on the scene and a veteran of Ricky Nelson’s band (and later the leader of Elvis Presley’s TCB ensemble).

“James Burton had heard Clarence and started offering him session work — ‘I’ve got more work than I can do.’” says Diane Bouska, who married Roland White in the 1980s and performed with him until his death in April 2022 at age 83. “So Clarence started doing electric guitar session work.”

Clarence found himself working on Nelson sessions, as well as the Monkees and as lead guitarist on the album Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, the first project for Clark after leaving the Byrds. Then Chris Hillman, still in the Byrds, brought him in to play on a couple of songs for the band’s Younger Than Yesterday album, which led to more work with the group (including on Sweetheart of the Rodeo) and ultimately full membership in the last version of the band.

As such, Clarence wasn’t around much for the 1967 Ash Grove shows or the radio sessions captured for this reissued album, though Fox says that he seems to be on at least one of the songs. Shortly after that, Roland was hired by Bill Monroe and moved to Nashville. He and Bush did reconnect in the early ‘70s in the proto-newgrass band Country Gazette, which also featured fiddler Byron Berline, an LA mainstay who had played a handful of dates with the Colonels.

Clarence made his place with the Byrds, showcasing his dazzling skills on a B-bender — a Fender Telecaster modified by him and Gene Parsons, the band’s then-drummer, with a lever attached to the strap allowing him to bend the namesake string to simulate the sound of a pedal steel. He also continued doing sessions for Joe Cocker, Randy Newman, the Everly Brothers, Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, and Rita Coolidge, among others, as well as returning to his acoustic roots in Muleskinner, a progressive bluegrass-swing group with mandolinist David Grisman, fiddler Peter Greene, banjoist Bill Keith, and guitarist Peter Rowan, a precursor of the groundbreaking David Grisman Quintet.

Then in 1973, Clarence, Roland, and Eric came back together as the White Brothers (sometimes billed as the New Kentucky Colonels) for shows in the U.S. and Europe. Following a show in Palmdale in the Southern California, Clarence was hit and killed by a drunk driver as he and Roland were loading equipment into their car. He was just 29.

It is hard to extricate the Colonels’ legacy from that of Clarence.

“The main thing was Clarence White’s guitar playing,” says country star Marty Stuart in an email. Stuart is arguably the leading authority on all things Clarence White, not to mention the owner of the original B-bender, which he played alongside Byrds founders Hillman and Roger McGuinn on the 2018 tour marking the 50th anniversary of the Sweethearts album.

“To me they are still influential because of the level of musicianship and they remain as the beloved founding fathers of the Southern California bluegrass scene. I had dinner with Gene Autry one time and he said, ‘I didn’t say I was the best singing cowboy, but I was about the first and the rest don’t matter.’ I would place the Colonels as field correspondents, national ambassadors for the world of bluegrass music in Southern California when barely anyone else was there to help out. They also introduced bluegrass music to an entirely new generation of listeners that old timers might not have gotten to.”

But there’s more to it than just Clarence. McNees, who wrote several of the few original songs the band did in the early days, found that out when he learned that modern country-rock band Blackberry Smoke had done a version of one of them, “Memphis Special,” on the 2003 album Bad Luck Ain’t No Crime.

“I didn’t know anything about it,” he says from his home in Thousand Oaks, north of Los Angeles. “I got a phone call [a while later] from an accounting firm to make sure I was the writer. Lo and behold, a couple weeks later I got a real nice check for royalties not being paid and after that another. After that I became an acquaintance of the singer [Charlie Starr]. Then they were coming to Los Angeles to play the House of Blues. I couldn’t go so my son went for me. I said, ‘Ask where they got the song.’ He came back and told me, ‘Well, he said that when he was nine years old he was watching The Andy Griffith Show and saw these guys playing bluegrass and asked his father to buy our album for him. Glad he did.”

And glad it wasn’t one of the Dillards’ episodes.

Is it any surprise that there is still enough interest in the Kentucky Colonels to merit this new release? Marty Stuart has one crisp, pointed word to answer that question.

“No.”

Album cover illustration by Olaf Jens, courtesy of Sundazed.