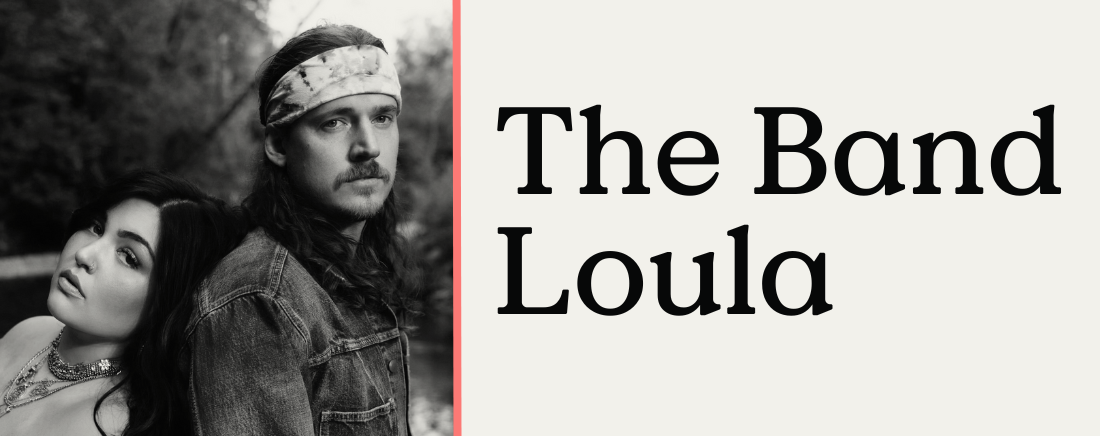

If you’ve spent enough time within the sacred walls of a sanctuary, chances are you’ve witnessed or experienced church hurt – the trauma foisted upon others, by others, under the guise of scripture. Logan Simmons – a woman of deep faith and former worship leader who grew up in the church and cultivated her powerhouse vocals in the sanctuary – knows this too well. Together with her best friend and musical other half, Malachi Mills, Simmons channeled her wounds into The Band Loula’s single “Running Off The Angels,” an unfiltered exposé of damage done in the name of religion. Reaction has been overwhelming, as both song and video cut deep into listeners who recognize their own stories in the song.

This isn’t the first time the songwriting team of Simmons and Mills has made a bold statement. Tackling and confronting dark subjects usually swept under rugs and stuffed away in family closets seems to be their comfort zone. “Marshall County Man” began as their take on the traditional “murder ballad.” However, with its challenging lyrics and graphic video, the song quickly pivoted to an outcry about domestic violence and generational trauma, speaking loudly to systemic treatment of victims/survivors.

All is not grim in the world of The Band Loula. Far from it, in fact, as evidenced on their debut EP, Sweet Southern Summer, which was produced by Brothers Osborne’s John Osborne, with additional production by Greg Bieck. The six songs – “Running Off The Angels” among them – are a slice of life reflecting Simmons and Mills’ experiences growing up in Gainesville, Georgia, up to the present. The two attended school and sang in church together and became best friends along the way. At one point, their paths diverged. Mills pursued music full-time, including an American Idol audition (fun fact: Luke Bryan voted him a firm “no”), a solo career, and writing for and working with other artists, while Simmons built a successful photography business.

Music, however, had the strongest hold, bolstered by their enduring friendship. They launched The Band Loula in 2020 and officially debuted as such in 2022. They independently released singles recorded at Ivy Manor Studios, where they worked with close friend, co-writer, and guitarist Gary Nichols. Universal Music Publishing Group discovered, auditioned, and signed them in 2023; Warner Music Nashville did the same the following year. They spent 2024 on the road with Brothers Osborne, Ashley McBryde, Paul Cauthen, Brent Cobb, and Elle King.

This year, The Band Loula and their band – Gary Nichols on guitar, Jamie McFarlane on bass, Justin Holder on drums, and Diana Dawydchak on fiddle – are spending the summer touring with Dierks Bentley and Zach Top. When they spoke again with Good Country, they were weeks away from a date at Madison Square Garden and from their Opry debut, and equal parts overjoyed, incredulous, and grateful for all that has happened and is yet to come.

Let’s begin by having you introduce each other to readers.

Logan Simmons: I’m Logan, I’m half of The Band Loula, and Malachi is the other half who leads us very well. He’s been writing songs and playing music since he was 16 or 17, and we’ve been friends since we were 14, so I’ve gotten to watch that whole journey. He had his own career going, added me into the mix once we found that we had some magic, and we created The Band Loula. We bring different things to the table. He is an incredible singer and guitarist, and he’s the planner of the group. He’s got all the logistics underway. He knows what everybody’s doing and at what time. I’m pretty much the opposite of that. I’m very Type B. He keeps us together. He’s definitely the glue of the band.

Malachi Mills: I’m Malachi, and as Logan mentioned, we met when we were 14 years old. When I first saw her, she was performing a skit onstage with her cheerleading squad doing a Justin Bieber dance. We were friends through high school, went to church together, and sang together in church a handful of times. I also got to watch Logan’s career as a photographer. She started when she was still in high school and now she is critically acclaimed. Along that journey she learned so much about visual arts, marketing, and things that are a major part of her role in The Band Loula. She is the brains behind our social media and she’s an absolute visionary. Big visions, big emotions, a great songwriter, and obviously an excellent singer. Half the time I’m just trying to keep up with her vocally.

Logan, is it correct that you first heard Malachi sing at a Relay For Life event?

LS: Yes. It was the same event he’s referring to. We both signed up for karaoke, essentially. I saw him first. He was onstage singing “When a Man Loves a Woman” by Percy Sledge. I did not see him when I was onstage in my Justin Bieber outfit, with Ray-Bans on, because I couldn’t see much of anything! But yeah, that was the first time I ever saw him. That’s how we met.

View this post on Instagram

Universal Music Publishing Group came to see you at a gig in a Gainesville parking lot. What, exactly, is the story?

LS: In April 2023, we got an email from Ron Stuve at Universal Music Publishing Group. We had plans a few days later to play under a little pop-up tent by the lake in Gainesville. It was a Food Truck Friday event. Ron came to Georgia with his family and saw us play there for the first time. We didn’t expect this at all. At first, we thought the email was spam because we didn’t have any followers. We were a very small band. But Ron came and he believed in us.

How did he find you?

MM: Ron was on his iPad early one morning and saw an Instagram video of our song “Getting Clean.” He didn’t know how to save it, so he left his iPad open on the charger, for hours, after he had woken up, so he could step away! Thankfully, we were still there when he came back. He submitted a form on our website to email us. We only had that video at the time. It had about 10,000 views, which, when you’re a small band, is a lot. But in the grand scheme of how many views happen daily in the world, that was pretty small odds, so we definitely think it was meant to be.

It’s quite a jump from a food truck gig to Madison Square Garden. Can anything prepare you?

MM: There’s nothing we could have done to fully prepare for the mad rush that has happened over the past two years of our career. It’s been a very quick rise, a lot of opportunities that came fast, but in a weird way we’ve had peace about it the whole time. With our separate journeys, we’ve been able to build the skill sets to come together and be ready for the opportunities that have been given to us. All that to say, stepping out onstage at Madison Square Garden … you can call us back in a couple weeks and see if we feel the same!

LS: There’s nothing to prepare you for something like that except thoughts, and prayers. We’re not even halfway up the ladder. It still feels like we’re babies and a lot of what happens to us doesn’t really hit us until it’s happening or after the fact. We don’t expect anything. We just put our heads down, work, hope that what we believe in is connecting with people, and we’re really thankful when it does. We’re grateful for all the opportunities we’ve been given.

How did your separate journeys help lay the groundwork for the band?

MM: I’ve always had a strong love for songwriting. I looked at the artist side of it as supplementary to that. It’s given me an outlet. I never felt I had a place as an artist until The Band Loula, because there’s so much identity and chemistry in what we have together. All that experience came into play when we started to really commit to this, for sure. You learn what to do and not do, and I was able to bring a lot of what we probably shouldn’t do on our journey as artists, because I had lived and learned in some of those areas.

LS: It taught me a lot about life in general. I shot my first wedding when I was 14 or 15. My dad drove me. One of my cheerleader friend’s sister asked me to shoot her wedding, which is a very important thing. I couldn’t believe she asked me to do it. I learned a lot over twelve years of doing it professionally. You can’t replace the connections you make in that kind of business, where you deal with people of all ages and from all walks of life every day. At one point I was traveling every week, meeting new people, driving across the desert in a podunk car, and sleeping in the car, just to make it to the next shoot. It’s life lessons and learning about yourself.

Now that we’re in the music industry, I find myself using those tools. The photography world is a lot of people-pleasing and deadlines. It tests your strength and emotional intelligence, which is a real skill that you can use in every industry. I feel like I have mastered some corners of that, of being emotionally intelligent, reading people, making real connections, and how that can get you to the next step. Every milestone and opportunity we’ve gotten as the band has been a product of how well we treat the people around us and how we reciprocate the love that’s given to us. I’ve learned how to master that because of all the people that were put in my life during my photography years. I’ll never forget what I learned and the people I met. I [recently] had some backstage guests at a show with Dierks Bentley and it was two people I shot a wedding for in Maine a few years ago. Watching those people become our fans is irreplaceable for me.

What were your goals for Sweet Southern Summer?

MM: Our main goal was to show our listeners a different side of us. A lot of the tracks we’ve put out so far have done a great job of showing a more emotional side. Usually, people don’t come in off the bat with emotional songs. They come in with lighter or more topical songs. We came in with a pretty heavy side of us, and I think that’s why our fans appreciate us. But we wanted to show our fans that we also have songs that are a little less gothic and more bluesy and rocking and soulful.

LS: With this EP and beyond, the goal is to show a different side of us each time, so our fans feel like they are learning more about us, and the relationship gets deeper and deeper. But we also are keeping the common thread of who we are and who we’ve always been. This EP is so exciting because it’s fresh and different, but it is obviously working toward a goal of a debut album. I think these songs will maybe surprise people and keep them on the journey. We really believe in this EP and we hope it connects with folks.

You’re both very open about your faith. How does that guide you and keep you grounded?

MM: A big hinge point in faith is being grateful. Whenever you’re grateful, you’re reminded where opportunities and things in life come from. To think that we could have put all this together with our own two hands would be egotistical. We’ve worked very hard and intentionally, but we believe that if we take care of the small steps, put one foot front in front of the other, and stay grateful for the opportunities that are coming, God will continue to bless us with those opportunities and take care of the big picture.

LS: I agree. Malachi has been a really good leader in that way to point us toward the bigger picture, which is having faith and believing that God will get us where we need to be. I led worship for a long time, but I had a falling out with church and a large moment of my life that was hard to believe that something … I don’t know. It’s a lot to chew on. For the past few months it’s been lovely to watch Malachi lead our band in prayer and keep God and our faith at the center, because I was not previously doing that. I had a really hard time getting past some church hurt and realizing that God is the reason why we’re here and why we’re doing this. That is what I believe now, and that’s what I’m getting back to after a lot of trauma, a lot of hurt, and a lot of figuring things out.

Thankfully, that’s why God put us in a duo – because we’re two different people and we’re able to lead each other in different ways. I’ve continuously been watching Malachi lead in that way and help me regain faith. We like to keep that at the center of our band. I can’t walk onstage without him praying for us now. We both believe we’re not here because of us or something we’re doing with our two hands. It’s a lot more divine than that, and it’s a beautiful thing.

Church hurt is an inconvenient truth mostly swept under the rug, which speaks to the overwhelming positive response to “Running Off The Angels.” Did you also experience blowback?

MM: We don’t ever want to be divisive in any way. Our main goal, without being too specific, is to promote love first. We don’t want to promote judgment. There’s a lot of judging people before you even get to know them, and I think our songs do a good job of reminding people of that reality. I think the ones who get frustrated might be actively judging in that way, or maybe they’re coming to grips that they’re ready to change for the better.

LS: “Running Off The Angels” has been interesting for us, because we weren’t a hundred percent sure we were going to put it out when we first wrote it. It was very specific to my experience and it crosses some lines. We got a wonderful response. We went out on a limb a little bit and were like, “Let’s just post this on social media and see what happens,” and it went viral. There was a lot of blowback, too. On social media, in the Facebook world, people like to talk. They like to hide behind their keyboards. So we did get people who didn’t enjoy the song. But at the end of the day, you can write about experiences that don’t necessarily encapsulate who you will be forever.

When we wrote, “I quit church and never went back, sang my last red-covered hymn,” that isn’t necessarily completely true to me now. But the song has so many truths to it, and it’s something that needs to be said, because people are struggling every day with church hurt and trauma, and it’s not talked about enough. There are wonderful communities and people and churches out there, and I’m thankful for that. And then you have wonderful churches that have people in them with bad intentions or who don’t understand how to treat people. We hope that people always turn toward love, if they can. That’s all that song is about. But it was wonderful writing it, recording it, teasing it, releasing it, and gaining new fans from it.

One of your social media posts says, “Songwriting is an ugly truth. It makes you dig through trauma with your hands, open up an emotional filing cabinet that you locked away and somehow come out on the other side with something you’re proud to sing in front of folks.” How does music help you heal that trauma and protect your mental health?

LS: Music is everything. I’m very much an empath, so music and songs that make me feel something shape who I am and affect me in different ways. That sentiment has amplified now that I’m a songwriter, because I get to create the music that is helping heal me. It’s not just I hear a song that pertains to me and takes me to a place. Now we get to write music that is about what we are feeling and what we experience. That’s therapy. It has deeply affected who I am. It has healed me in many ways. Most of the trauma I went through was recent, in my twenties, so this career choice, leaning into this passion and into music, happened exactly when it was supposed to happen, because it has helped pull me out of some deep, dark places.

MM: I agree. Songwriting and music are very cathartic. The fact that there is a song in my heart, in my brain, inside of me, and having the ability to get it out into the world, is very healing. Also, when you’re able to say things that other people don’t feel they have the words or the song inside of them to say, that is very special, because it makes you feel like you’re really making a difference.

Photo Credit: Sara Katherine Mills