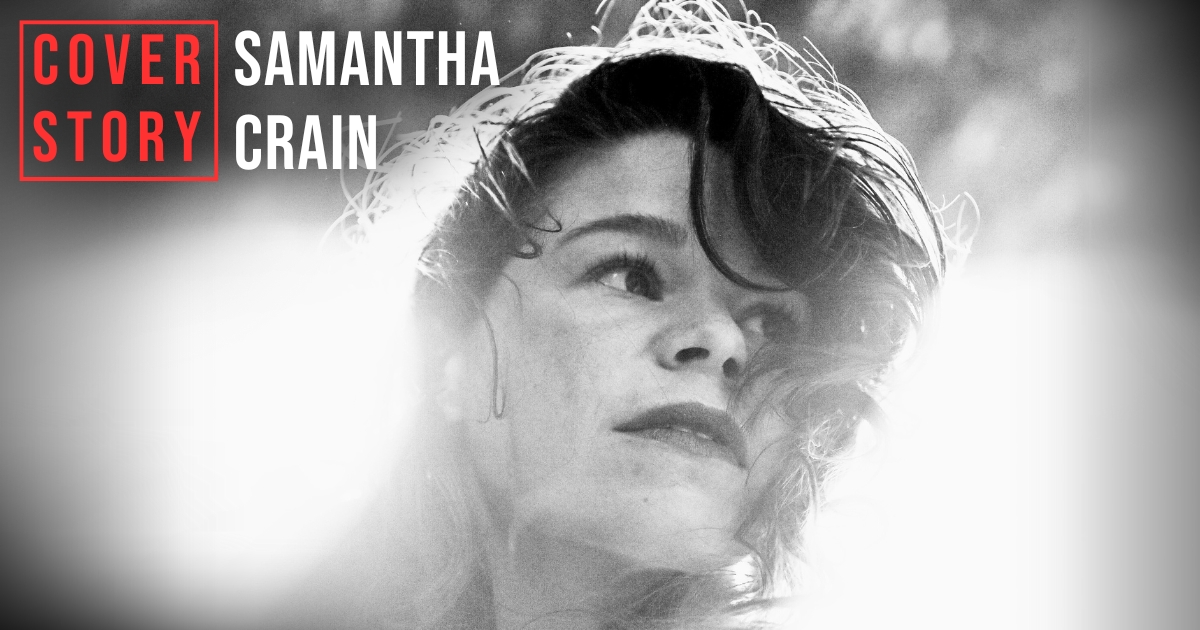

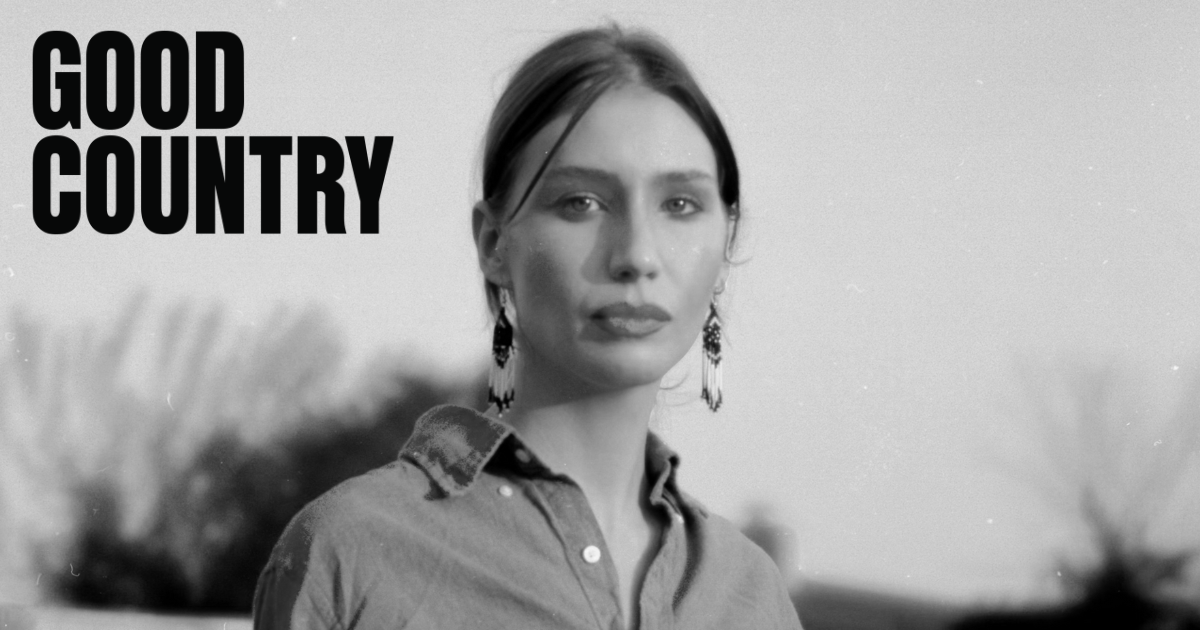

Banjoist, songwriter, and podcaster Hilary Hawke has had a meandering journey with music, starting with guitar and clarinet before finding her musical home in the banjo and “becoming obsessed with it” during her late teens. Inspired by the storied folk tradition of upstate New York, Hawke now makes her home in New York City, where she leads her own bluegrass band and plays for various other groups as part of a close-knit roots music community.

New York City is uniquely ripe with gigs in theater and Hawke has found herself playing on Broadway for musicals such as Oklahoma! and Bright Star and composing music for puppet shows, among many other diverse projects. She has also started her own podcast, Banjo Chat, where she speaks about the banjo and banjo music with folks that love the instrument as much as she does.

BGS connected with Hilary Hawke to discuss the making of her new album, Lift Up This Old World, her time on Broadway, her new job teaching bluegrass at Columbia University, and more.

Can you tell me a bit about how you got started on the banjo?

Hilary Hawke: I actually went to school for classical music on clarinet and guitar, but I realized I didn’t know how I was going to get a job in music or what kind of job I wanted… composition? Teaching? Music therapy? I got to a point where I was like, “This all seems very serious and I’m not actually having much fun with music.”

During that time, I was writing songs on guitar and I just picked up a banjo for fun, to do something outside of school. I grew up in upstate New York and we have a lot of folk music and a lot of great banjo influences up here like Tony Trischka, Béla Fleck, Pete Seeger, the Gibson Brothers. And, honest to God, it was just the thing I started creating music on all the time. I started playing it nonstop. I ended up moving into New York City just on a whim. There were lots of opportunities to perform and I was able to take some lessons with Tony Trischka. New York is like– you just think you’re going to try it out and then suddenly 5 years have gone by.

Influences like the New Lost City Ramblers, Mike Seeger, Bruce Molsky, and Fred Cockerham seem to be threaded through your old-time and bluegrass style. Do you have a specific moment you can remember that sparked your love for these musicians?

I think that it’s always through popular culture that you get inspired to dive into the deeper stuff. Alison Krauss had a record called Too Late to Cry and I remember I heard the banjo on that and was like “What’s that sound?” It was Tony Trischka playing on her record. Similarly, I heard the banjo on the Dixie Chicks’ albums and wanted to know how it worked. Through those more popular bands, I got interested in banjo. And then I went to the festivals and I heard about the old guys. People would give me rides and we’d be listening to their CDs in the car. It was a lot of word of mouth like, “Oh you gotta hear Fred Cockerham and Tommy Jarrell!”

You started teaching banjo in Brooklyn at the Jalopy Theatre back in 2006. How has that community influenced your growth as a teacher and performer over the last 20 years?

I really cut my teeth at Jalopy. I was there for 10 years or so and I was able to develop a curriculum for teaching. I learned how to tear things apart and break them down, as far as playing the banjo. I gained the skills I’m now using to teach at Columbia University. I think Jalopy is a great breeding ground for performers, artists, and teachers to develop. It’s open-minded and exploratory.

Tell me about your new album, Lift Up This Old World. Where does it fall in the trajectory of your music-making?

This is the third album I’ve released under my own name. The first album I made was more of a singer-songwriter album; writing songs was really my entry point into folk music. Then I released an instrumental old-time album. This one combines songwriting and picking, but it is much more bluegrass-forward.

I noticed that you play both clawhammer and bluegrass-style banjo on the record. How do you relate to the two different styles and where do you feel more at home?

I started with fingerpicking and got into bluegrass first, but I just wanted to do it all. I wanted to be involved with a wide range of music. Sometimes a person would ask, “Do you want to come play with my old-time band?” And I had to say no because I couldn’t play that style. I quickly realized I didn’t like to say no! I wanted to be able to do it. So I started learning clawhammer from some Ken Perlman videos and taught myself. Now I feel like they take up an equal amount of space in my life and I pick the style based on the music.

With my original material, I approach the banjo with the kind of song I want to write in my mind, so if I want to write a honky-tonk song I might use fingerpicking, but if I want to do something with a shout chorus, for example, I’ll approach with clawhammer banjo. I listen to a lot of Tim O’Brien and I feel like he does that, too. Being able to play both styles, I have a little bit more of a tool kit for what I want to do.

Tell me about your approach to songwriting. There are a lot of songs about lost love and relationships on this album, some about relationships with people, but even your relationship with New York City. “NYC Waltz” is a track I particularly love. Is there a common theme that you see that brings these songs together?

I think this record is about overcoming struggles in confidence, specifically struggles in the music industry. I had the realization that you have to be your own cheerleader, you have to believe in yourself, and find that happiness in yourself. If you’re doing what you’re supposed to be doing, things are going to happen. Making this album was me having the belief that I could do this thing, overcoming fears and doubts in myself, striving, and coming out on the other side.

The way you recorded this album, it sounds live in a way that is rare for modern recordings. Can you tell me about how the record was made?

We did it live to save money. We started a year and half ago and I didn’t have the resources to do separate tracking, so we rehearsed it for a couple of days and then just went in and tried to nail it. We recorded pretty much the whole thing live with a full band in Williamsburg, one day with each of two fiddle players, Bobby Hawk and Camille Howes, at Waldon Studios in Williamsburg.

Ross Martin [who plays guitar on the album] and I have been playing together for two years as a duo and we have worked up some of these songs over that time. I felt like these album songs were a good representation of the music we have been making for a good while now. “Dreaming of You,” the last song on the record, is the only one that we arranged and tracked out separately; it has a very different feel than the rest of the album.

Yes, I noticed that! It’s a bit orchestral.

Yes, that was all arranged and written out by me. I produced this album myself and I think going forward, I would like to do more collaboration with visionaries and people I trust in the making of a record. I think I learned that it’s great to have another trusted set of ears for a project. It’s hard to step away and see things for yourself. I have a pretty clear vision about what I want things to sound like, but you also have to be gentle and kind to yourself. It’s hard to find that line.

You also have a podcast about the banjo called Banjo Chat. Can you tell me about how that got started and how you’re enjoying it?

It’s good! It started because I had a lot of questions for banjoists about the way they write songs, form solos, and think about music that I didn’t hear asked or answered on other podcasts. Also, I wanted to amplify the voices of people whose playing I loved who were female identifying, queer, gay, minorities, or just didn’t really fit into a bluegrass or old-time genre with their music.

So I started this podcast. I got some new software for editing and now I do the research, recording, editing, and mixing all by myself.

Before I let you go, I wanted to ask you about your time on Broadway. In 2016 you subbed on Broadway playing banjo for Bright Star – a show that brought bluegrass and old-time to the stage in a major way. Looking back, how did that highly choreographed experience change your approach to live shows?

Bright Star does have a huge regional presence. For me, that was my first Broadway subbing gig, subbing for Bennett Sullivan. Being in that environment made me realize that when you play live shows you need to get out of your own head, you can’t just be standing up there not giving any energy out to the audience. You have to have a lot of love to give out and to have your message clear in your head when you’re performing. Be happy to be there.

That’s what I learned from the theater. All these people bought tickets to see the show, they’re here to see a show and have a good time – not to see you in your head worrying about your performance.

Photo Credit: Aidan Grant

Madeline Combs contributed research and interview prep for this feature.