The year’s most discussed, and in some respects, most controversial LP to date has been Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter. Its admirers have painted Beyoncé as a trailblazer for Black country artists. They cite her inclusion on the album of both past – like Linda Martell – and contemporary Black country artists, including Rhiannon Giddens, plus the foursome of Brittney Spencer, Reyna Roberts, Tanner Adell, and Tiera Kennedy, all featured on the update of The Beatles classic, “Blackbird” (stylized “Blackbiird”). They also cite Beyoncé’s Texas background as ample proof of her country roots and sincerity.

Others, notably contributors to The Washington Post and The Guardian, have attacked the 27-song project for a variety of sins ranging from overproduction to such emphasis on idiomatic variety that the result to their ears is faceless, forgettable music. Beyoncé herself has repeatedly said “It’s not a country album, it’s a Beyoncé album,” a line that can and has been viewed many different ways.

Still, there’s been a genuine explosion of interest in Black country music the past couple of years prior to the release of Cowboy Carter. It has resulted in a host of attention for artists ranging from Charley Crockett, Mickey Guyton, Miko Marks, Rissi Palmer and Brei Carter to established hitmakers like Darius Rucker and Kane Brown. But there’s one name that stands above all others as a key figure who’s been in the country music trenches over five decades. That’s author and songwriter Alice Randall, a superb novelist and academic. Randall, a Detroit native, made the move to Nashville from Washington, D.C. back in 1983, because she wanted to showcase her skills as a country songwriter and simultaneously wanted to demolish the widely held myth that the music had no links or connection to Black music and zero audience among African Americans.

“Yes, I faced open hostility and overt racism when I began,” Randall told Good Country during a recent interview. “There were plenty of people who looked at me and figured what’s this small Black woman doing here? But I wasn’t going to let that stop me.” Randall spent plenty of time attending songwriters rounds, plus examining and analyzing the songs that were becoming hits. In her book she pays credit to Bob Doyle, who was then a songwriter liaison at ASCAP. Doyle’s Bob Doyle & Associates is the longtime management firm for Garth Brooks. Another of her early Nashville mentors was singer-songwriter Steve Earle, whom she met through Doyle. She cites Earle’s willingness to address personal and social trauma and pain as an influence on her writing style.

Randall earned her first Top 10 country hit in 1987 with the Judy Rodman-recorded “Girls Ride Horses, Too,” which she wrote with Mark D. Sanders. She also launched the publishing company Midsummer Music (which she later sold), with the aim of aiding and developing a community of storytellers. She’d soon enjoy bigger success, becoming one of the first Black women to write a No. 1 country hit, when she and Matraca Berg co-wrote “XXXs and OOOs (An American Girl),” for Trisha Yearwood in 1994. (Donna Summer previously co-wrote Dolly Parton’s “Starting Over Again” in 1980).

Randall was also a writer on Moe Bandy’s top 40 hit, “Many Mansions.” Some other notable Randall milestones include writing the treatment for Reba McEntire’s “Is There Life Out There?” music video, which won an ACM Award and features a Randall cameo. In addition, she wrote and produced the pilot for a primetime drama “XXX’s and OOO’s,” which later aired as a made-for-TV movie on CBS.

But as Randall notes in her book, additional trials can come with success. Randall recounts how after the success of “XXXs and OOOs,” a music publishing executive pressured her into signing a contract before she had time to let her lawyers look at the paperwork. That move eventually led to Randall signing away much of her writer’s share of the song’s profits, an experience she called “part of my graduate school.”

Her new book, My Black Country (and its co-released, eponymous album), nicely combines personal reflection with historical commemoration and cultural examination. It highlights Black country’s finest performers and personalities, while noting that early country music was a far more interracial activity than many realized. “It’s amazing to me how many people don’t realize that Jimmie Rodgers recorded with Louis Armstrong, or that Lil’ Hardin was also involved in that historic recording,” she continues.

Randall cites Hardin as the mother of Black Country, the premier vocalist/harmonica soloist DeFord Bailey as the papa, multi-idiomatic master Ray Charles as the genius child, Charley Pride as Bailey’s side child, and the vocalist and TV/film star Herb Jefferies, also known as the Bronze Buckaroo, as Hardin’s stepchild.

She’s equally passionate about the frequent omission from country music histories and commentary of the contributions of Black cowboys. “I fight for all the Black cowboys who have been erased, all the country and western songs through the years that did not tell those stories,” Randall told Billboard magazine in an earlier interview. “When I wrote songs like ‘Went For a Ride,’ a lot of people did not realize they were Black cowboys I was writing about… but 20 or 30% of all cowboys were Black and brown in the 19th and 20th centuries, so it’s one of the ways that African Americans have contributed so much to the legacy of country music, is through cowboy songs.”

The book also chronicles a further lineage of Black country artists, including the Pointer Sisters and Linda Martell, as well as other artists like Sunny War, Miko Marks, Valerie June, and Rissi Palmer.

With 2024 being a big year for Black country, it’s only fitting that Nashville and the music world at large recognize and celebrate Alice Randall’s achievements. Last month she published the memoir, My Black Country (Simon & Schuster), while an accompanying LP, My Black Country: The Songs Of Alice Randall (Oh Boy Records), was also released.

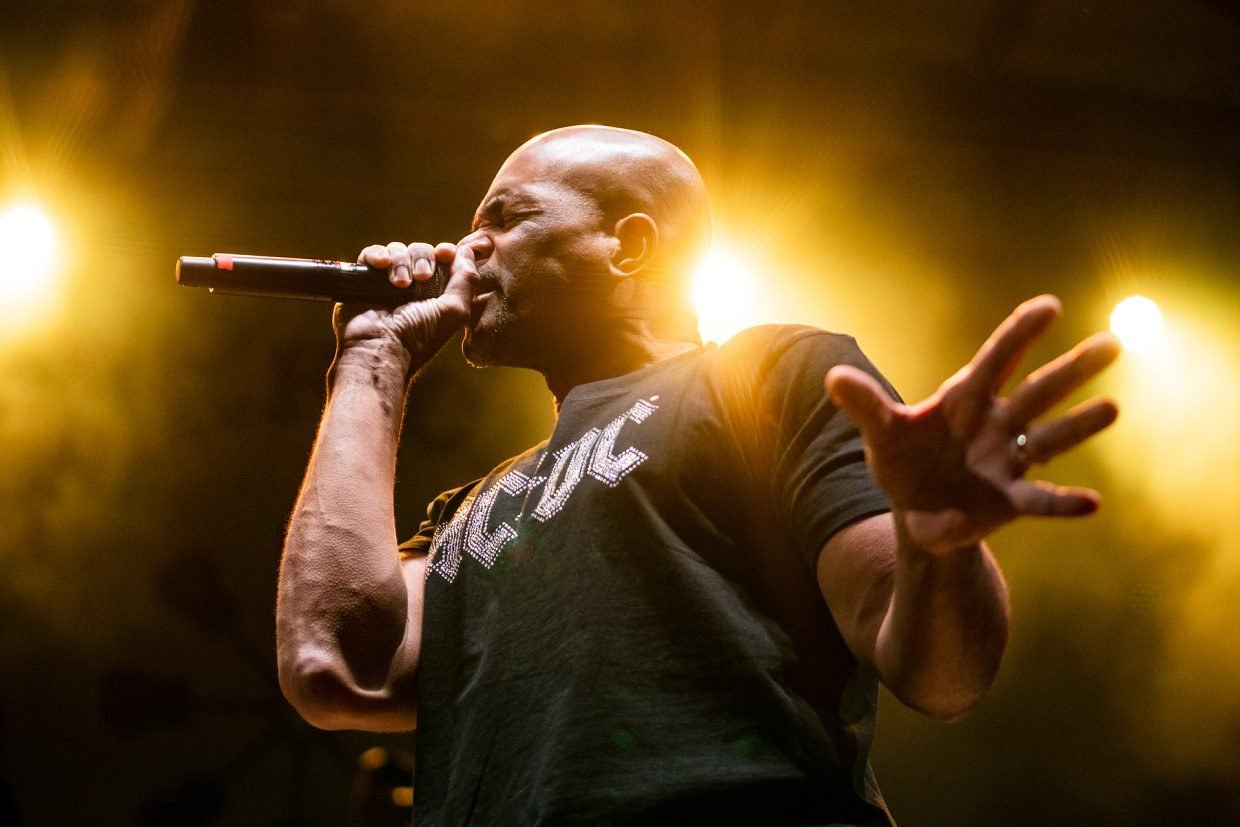

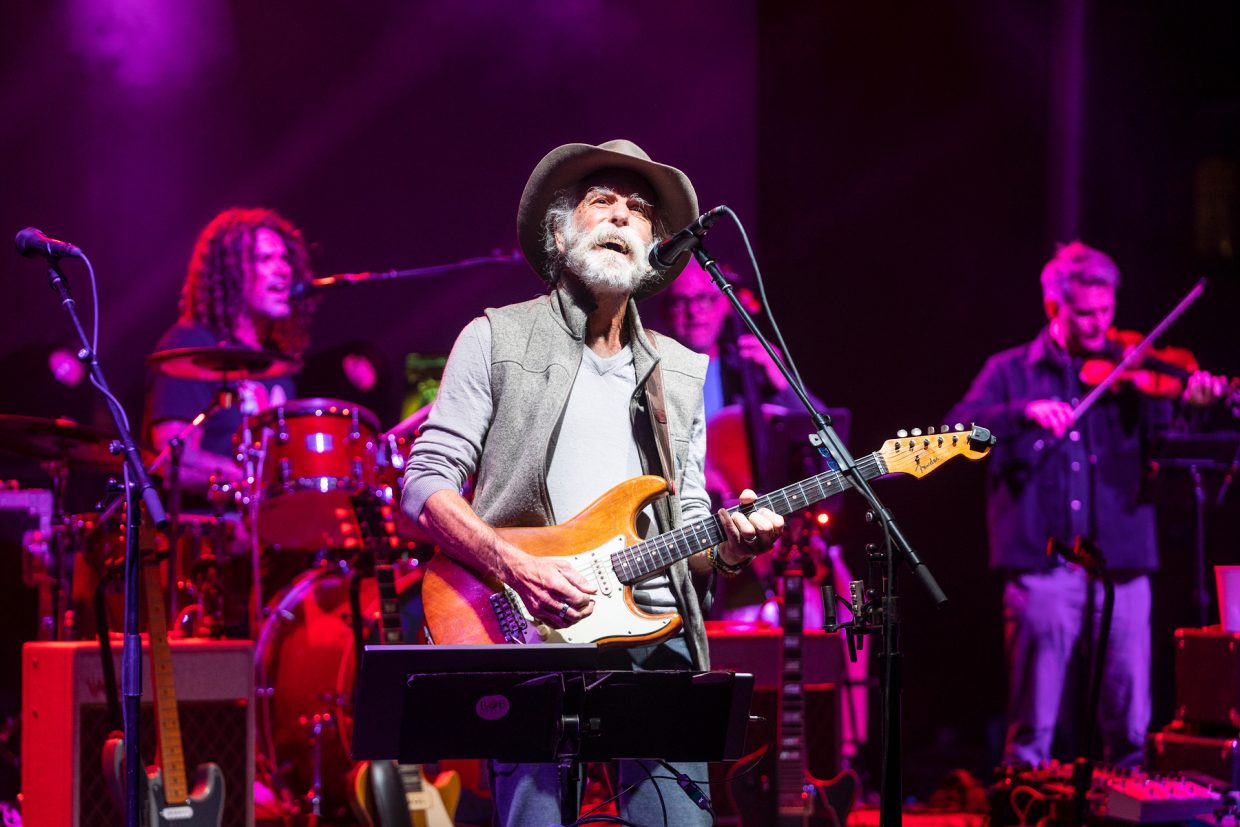

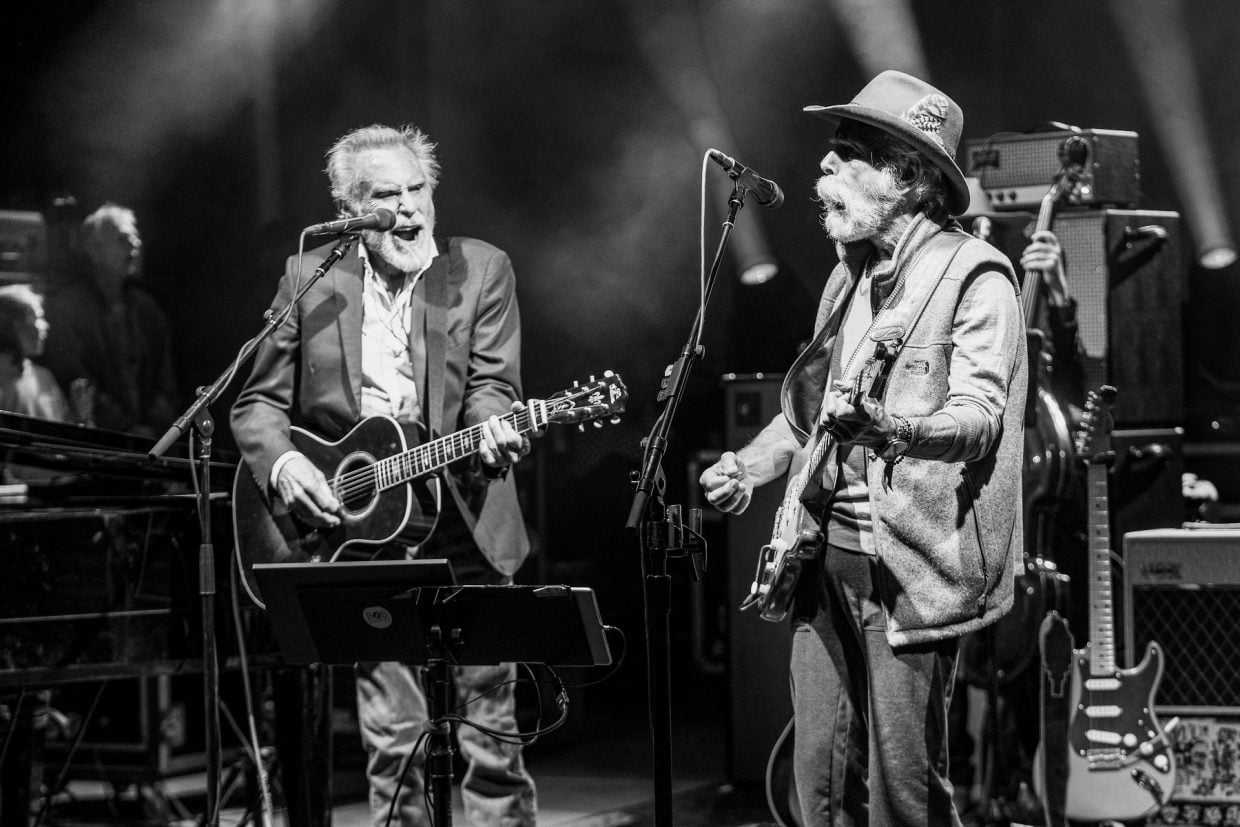

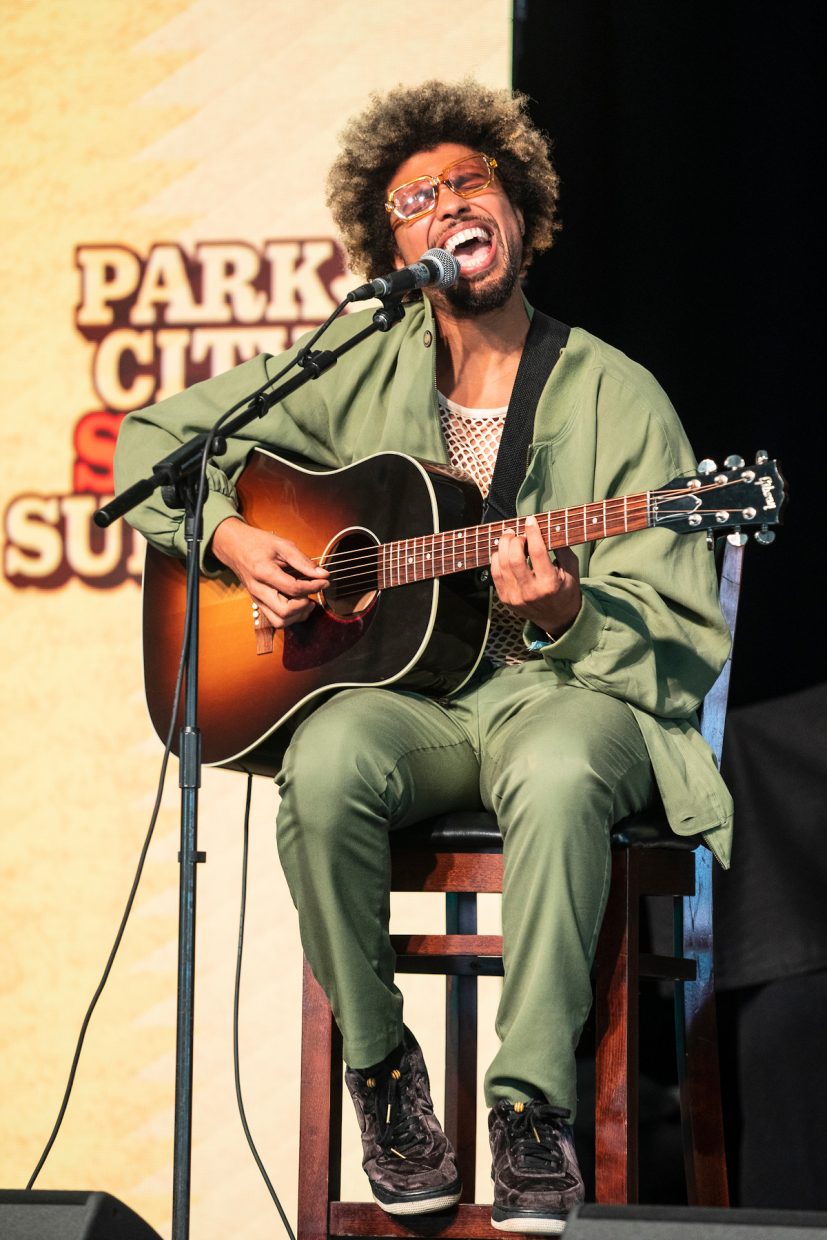

A pair of sold out events in Music City – a book signing at Parnassus bookstore and a combination celebration/Black Opry concert at the City Winery where contemporary Black country vocalists performed Randall tunes – were just the first events to honor the current Vanderbilt Professor of African American and Diaspora Studies as well as writer-in residence. Randall’s other notable literary feats include The Wind Done Gone, a blistering examination and parody of the book and film, Gone With The Wind.

During Black Music Month in June, Randall will appear at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture on June 7, and she’ll return to Nashville on June 15 for another in-person conversation about Blacks and country music.

Randall’s book traces her love for country to a family relocation. While growing up in Detroit, she was also a fan of Motown and even spent some time with Stevie Wonder. But upon moving with her mother to Washington, D.C., country became the dominant music she regularly heard. As a student at Harvard studying both English and American Literature & Language Randall says it was after closely surveying Bobby Bare’s 1976 song, “Dropkick Me Through Jesus (Through the Goalposts of Life),” she really began to understand the depth and breadth of country music storytelling.

That knowledge, along with her excellence as a lyricist and storyteller, resonates throughout the many memorable and unforgettable numbers on the album My Black Country: The Songs Of Alice Randall. The roster of 12 women selected to perform the various tunes features many of today’s finest country stylists. The honor roll includes Ada Victoria’s soaring “Went For a Ride,” Allison Russell’s glorious “Many Mansions,” Rhiannon Giddens’ routinely spectacular rendition of “The Ballad of Sally Anne,” and Rissi Palmer’s poignant performance on “Who’s Minding the Garden.” Randall’s daughter, poet and commentator Caroline Randall Williams, delivers a strong performance on “XXXs and OOOs.”

Randall credits Russell for introducing her to Ebonie Smith, better known for her work as a producer on Sturgill Simpson’s Grammy-winning album, A Sailor’s Guide to Earth.

And it’s no surprise Randall would conclude our interview by weighing in on the Beyoncé LP, herself.

“She’s the only Black woman to achieve those feats [No. 1 country single and album], but I don’t think she’ll be the last,” Randall concludes. “I’m more proud of the fact that there are so many great Black country artists out there, that the Black Opry is getting national attention, and that we’re finally putting to rest that garbage about country only being for white people.”

“In fact, to me, Nashville’s becoming a town for wild women, and for Black women to freely express themselves any way they choose.”

Photo Credit: Alice Randall by Keren Trevino.