For the first time in the thirty year history of the International Bluegrass Music Association a class of Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductees includes a woman in every act. The Hall of Fame, helmed by the IBMA and housed inside the Bluegrass Music Museum in Owensboro, Kentucky, infamously lacks women. Before this year’s class it included ten women, total, and only one woman — Louise Scruggs — had ever been inducted as an individual. All others had been inducted as members of bands, duos, or organizations.

This year Alison Krauss and Lynn Morris join the rarest rank of individual female inductees, alongside influential manager Louise Scruggs. The Stonemans — including Patti, Donna, and Roni — join the likes of songwriter Dixie Hall, who was inducted with her husband, Tom T.; Polly, Miggie, and Janis of the Lewis Family; Marion Leighton Levy of the Rounder Records founders; Sara and Maybelle of the Carter Family; and Hazel Dickens & Alice Gerrard.

To mark the occasion, we’re celebrating women in bluegrass who certainly deserve induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, beginning with this year’s inductees. The point is, there is no dearth of women in bluegrass, from way back in its earliest days before the genre even had a name to the big-tent-bluegrass present, and many of whom are more than qualified for inclusion in this hall of honor — as innovators, ambassadors, creators, pickers, and forebears, all.

Alison Krauss

Arguably the most well-known bluegrass musician to achieve mainstream success, Alison Krauss is a no-brainer addition to the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame. With her stellar collaborations — with Robert Plant, James Taylor, T Bone Burnett, and so many others — her bluegrass bona fides, her technical prowess as a fiddler, her crystalline and influential vocals, and her unparalleled skill for song interpretation she’s the perfect multi-hyphenate bluegrasser to demonstrate to veteran fans or the uninitiated passers-by what the Hall of Fame is all about. Because, no matter how far Alison Krauss may stray from bluegrass, everything she does remains firmly rooted in her ‘grassy foundations.

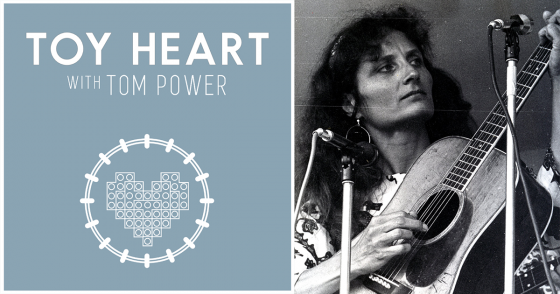

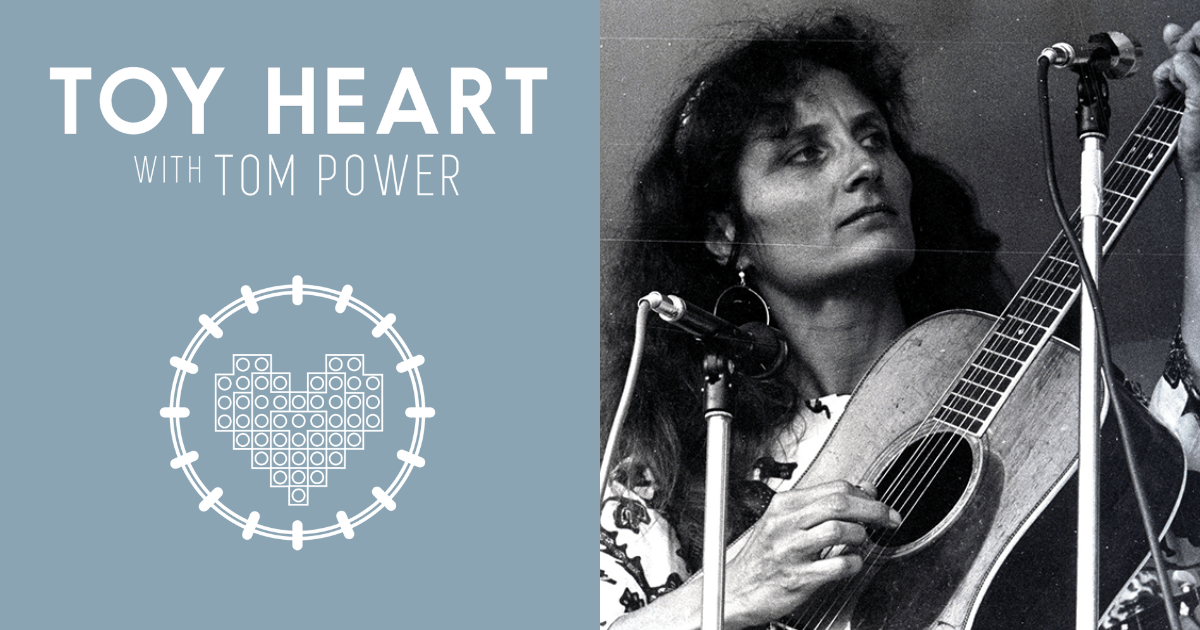

Lynn Morris

Lynn Morris remains a criminally underappreciated figure in bluegrass, partly due to her career being prematurely ended by a near-fatal stroke in the late 1990s. In the decades prior, this IBMA Award winner was a powerful and influential banjo player, bandleader, and community-builder, carving out a pathway to success in roots music for herself — given that no pathways were being made available to women like her. Morris’ brand of bluegrass was unflinching, driving, and gritty, and to this day it continues to defy stereotypes about what women can contribute to a music that often holds up maleness and horse race-style competition as currency. While at the same time, she retained a level of tenderness and openness rare in masculine-centered bluegrass. Hopefully this induction will spotlight Morris’ important role in bluegrass’ golden age during the ‘80s and ‘90s. “Love Grown Cold,” a semi-viral hit for Morris on many a bluegrass social media page, is merely the tip of the iceberg of what will be this Hall of Famer’s long-lasting legacy in this music.

The Stoneman Family

Ernest “Pop” Stoneman, father and figurehead of country’s legendary Stoneman family, was the man who started it all. No, literally. Pop is credited with being a keystone picker, performer, and pseudo-producer of 1927’s Bristol sessions, which later came to be considered as the “big bang of country music,” the beginning of the genre’s commercial fortunes. His family of pickers, including Donna, Roni, and Patti, became stars of stage and screen thanks to their showmanship, homespun vibes, and blistering-fast picking. The impact of this musical family on country, bluegrass, and Americana music — as a unit and as individuals — can simply not be overstated. From Hee Haw to the Grand Ole Opry to winning a CMA Award to international tours with their own group and as side musicians, the fingerprints of the Stoneman Family are all over American roots music across the globe.

Wilma Lee & Stoney Cooper

At one point, Wilma Lee & Stoney Cooper were perhaps the most famous bluegrass act in the world, landing several singles and tracks in Billboard’s Hot Country Chart in the ‘50s and ‘60s — notably landing four songs in the Top 10. Not on a bluegrass chart, because such a thing did not yet exist, but on the country chart! Granted, at that time bluegrass was still considered simply a subgenre of country and hillbilly music, but imagine not just one “Wagon Wheel”-level hit to their name, but a handful! And somehow, in modern times, Wilma Lee & Stoney are at best relegated to footnotes and asides. Bluegrass has always been a commercial genre and the commercial success of this pair is alone worth induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame, all their other achievements and accolades notwithstanding.

Ola Belle Reed

Ola Belle Reed is more than “I’ve Endured” and more than “High on the Mountain.” A Western North Carolina songwriter and picker, Reed typified the politically- and environmentally-conscious, subversive, and grounded style of musicmaking by Appalachian women who lived through the many upheavals and uncertainties within the region and around the world during the twentieth century. Her songs, like “Tear Down the Fences,” highlight that the south, Appalachia, and the people who live there are not monoliths. Just as Reed’s catalog of influential music is not a monolith, either. Truly a glaring omission from Bluegrass’s hall of honor.

Sally Ann Forrester

Born Wilene Russell, “Sally Ann” or “Billie” Forrester — wife of fiddler Howdy Forrester — was one of only two women to have ever been members of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys. (The other being Bessie Lee Maudlin, another prime candidate for Hall of Fame induction and inclusion in this list.) With the band, Forrester played accordion and sang as well as “keeping the books.” Inducting the women who were Blue Grass Boys, members of THE titular band of bluegrass, just makes sense! But with Forrester, it also represents an all-too-rare opportunity to canonize a bluegrass accordionist for the ages. Why wouldn’t we want to do that!? Take a listen to her accordion fills on “Rocky Road Blues” and just try to come up with a reason why bluegrass accordion isn’t more popular nowadays. Besides the obvious reasons.

Rose Maddox

Rose Maddox is traditionally credited as the first woman to cut a bluegrass album, recording Rose Maddox Sings Bluegrass in 1962 for Capitol Records and including many a bluegrass hit, like “Footprints in the Snow.” Maddox also marked the beginning of a series of women vocalists and musicians in bluegrass who could accomplish the high lonesome sound for which men like Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, the Osborne Brothers, and others were famous. Women who sang old-time and country up to this point often had rounder, more full, resonant, and rich voices, where men in bluegrass were seemingly attempting to shout tenor to dog whistles. Sexists weren’t sure women could replicate that testicles-in-a-vise-grip sound, but Maddox’s powerful voice immediately commands the same attention – and respect – of the highest and most lonesome. To think there used to be a time when people actually thought (or pretended to think) women couldn’t sing bluegrass!

Elizabeth Cotten

A pillar of American folk music, Elizabeth Cotten’s influence and impact knows no bounds, reaching far from downhome blues, ragtime, and old-time and into bluegrass, folk, Americana, rock, pop, and beyond. Her songs and her playing style continue to influence bluegrass today, but Cotten’s true legacy, one that will stretch on into infinity, is that her existence stands as permission for the Other – for marginalized folks like herself, a Black, working class artisan and musician from the South – to exist and to take up space within these historically white and often forbidding and exclusive roots music communities. Elizabeth Cotten is proof positive that the contributions of Black folks to American roots musics, including if not especially bluegrass, were truly seminal, essential, and vital to the music growing and developing into the entity we all love today. Elizabeth Cotten would be an excellent and unimpeachable first Black and African American inductee into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame. Let’s make it happen.

Buffalo Gals

In the 1970s the group considered to be the first bluegrass lineup of all women was Buffalo Gals, including Martha Trachtenberg, Susie Monick, Carol Siegel, Sue Raines, and Nancy Josephson. Their first and only record, First Borne, is finally available digitally and via online streaming platforms, but up until recently was largely forgotten. We featured First Borne in our list of the 50 Greatest Bluegrass Albums by women and retold a now-infamous story about the Buffalo Gals performing in their sleeping bags when a festival promoter gave them a set early in the morning because, you guessed it, who would want to see women perform bluegrass!? Hearing this whimsical, zany mash-up of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” and “Loco-motion” we’d make this group headline. Just sayin’. With bands like Della Mae and Sister Sadie enjoying success and acclaim at all levels of the IBMA, perhaps it’s time to pay tribute to the all-women lineups like the Buffalo Gals who came before and blazed the trail.

Gloria Belle

A woman for a Sunny Mountain Boy! Gloria Belle is most famous as a member of Jimmy Martin’s backing band, but it would almost be an insult to reduce her career to having spent time in the shadow of the King of Bluegrass. She was a fantastic picker, multi-instrumentalist, and singer and the first woman to ever release an album on longtime bluegrass label Rebel Records. In 1999 she received IBMA’s Distinguished Achievement Award after a handful of decades of nonstop recording, touring, and performing in bluegrass. She even made an appearance on the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s fantastically popular Will the Circle Be Unbroken album. Another case of an underrated woman who is constantly referred to on the back end of an ampersand after a man or men, Gloria Belle is a perfect example of a woman who deserves induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame on her own merits first and foremost.

Dolly Parton

Though she’ll often refer to it simply as “mountain music,” Dolly Parton is as bluegrass as they come. Albums like The Grass Is Blue, Heartsongs, and Trio demonstrate this fact to an obvious degree, but it’s worth pointing out — especially within the context of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame — that Parton’s bluegrass runs deeper than just being an offshoot of her musical expression. With the shows and festivals at Dollywood, her collaborations with artists like the Grascals, Rhonda Vincent, and Alison Krauss, and her longtime commitment to philanthropy in her home region of East Tennessee and abroad, Dolly is the perfect example the Hall of Fame could utilize to communicate the importance and value of taking bluegrass ideals and spreading them around the world. Plus, who wouldn’t want a ticket to the IBMA Awards show at which Dolly Parton would be inducted? (Pro tip: Dolly has actually attended the IBMA Awards and performed once before, when The Grass Is Blue was nominated in 2000 and Marty Stuart hosted. Let’s please recreate that show. Please.)

We could continue this list into infinity, and that’s exactly the point. Artists and bands like Alison Brown, Laurie Lewis, Missy Raines, Kathy Kallick, Blue Rose, Emmylou Harris, The Whites, Patty Loveless, and so many others are waiting in the wings, qualified, ready, and willing to step up and thrive under the mantle of Bluegrass Hall of Fame induction. And plenty of young women, femmes, and non-binary folks are waiting to have examples to look up to, to signal to them that bluegrass can be a place where they can also make a home. The concept of a Hall of Fame may seem like an unimportant or inconsequential or self-serving enterprise at times, but it can be so much more than that! We can supply those examples. Let’s do it.