The SteelDrivers’ new lead singer, Kelvin Damrell, already grasps the driving force behind the band, which is marking its 12th year with a brand new album, Bad For You.

“You couldn’t play our songs if you weren’t passionate about what you were doing,” the Berea, Kentucky, native believes. “It wouldn’t sound right at all, in any position in the band. From the mid-range harmony part to the hardest-playing guitar riffs, to the hardest-playing fiddle, it wouldn’t sound nearly as good as it does if you didn’t love what you were doing, and playing with as much passion as you could.”

On Bad For You, Damrell steps into a role once filled by Gary Nichols and Chris Stapleton for the group’s first album since winning a Grammy with 2015’s The Muscle Shoals Recordings. All five of the SteelDrivers — Richard Bailey, Damrell, Mike Fleming, Tammy Rogers (whose daughter discovered Damrell on YouTube), and Brent Truitt — invited BGS over for a chat.

Kelvin, how long had you been in the band by the time you went into the studio?

Kelvin: Goodness, how long has it been now? I joined in October 2017. I was just so looking forward to the release date of the album that I’d forgotten when we went in.

Mike: He had to go to boot camp first. [Laughs] Bluegrass boot camp! We had to take him out of Kentucky. He had his first airplane flight. You saw the ocean for the first time, right? You left a lot of things laying around. [All laugh] You went through airports with knives when you shouldn’t have. But listen, it was good! We all got comfortable with each other, and we needed some time just to feel that, and it got to that point.

Kelvin: When I joined the band, I was really unsure about what was going on, about my position. I had made the cut as far as getting to be in the band, but Brent kept telling me we needed a couple of months to see how we jibe together. I thought that was just him saying that, but it was the truth. We switched vehicles pretty regularly and I rode with different people. We really saw how we jibed together before we made a full decision on whether we were going to keep me, or if I was going to go back to sweeping chimneys.

The song “Bad For You” has such a cool groove. You sent it out as your first single and you named the album after it. What is it about that song that is special to you?

Brent: To me it was the perfect fit for this band. It was the song that hit me right out of the chute. It encapsulates the sound. It’s really edgy, and we’re a little bit on the edgy side of bluegrass.

Mike: It was one of the strongest songs, as far as that kind of feel. It’s like a “Here we are!” kind of song. You know, “Look out!” The way Kelvin sang it, Tammy told him, “Sing it like a rock ‘n’ roll singer.”

Kelvin: I almost got emotional when we played it for the very first time. I really did, that’s the truth. The first night we debuted it, after we hit that last big note, I almost did get a little emotional because it’s like something is finally coming to fruition with my position in the band. I’d done all this other stuff that vocally belonged to Gary and vocally belonged to Chris, and now this one vocally belongs with me at the lead. And man, that three-part harmony! Everything about it was good, and it really did make me emotional.

I’m glad you mentioned harmony because that’s a really important component of this band that doesn’t get talked about enough — how well you can stack those voices.

Tammy: Thank you. But you’re exactly right, I think that’s always been a really strong facet of the band. It’s this rock ‘n’ roll lead singer with this really strong three-part harmony coming in on the chorus. From a writer’s perspective on this album, I thought about that a lot, and how that was still a big part of the sound, and to keep that consistent because I think that does set us apart.

Brent: In our live set, I’m thinking of one or two songs that end with the vocal trio by itself, doing the swell and bending into a note, and the crowd loves it every time. It’s a big part of bluegrass, period, but it’s a big part of our music too.

Brent, how would you describe the SteelDrivers’ sound?

Brent: For me, personally? It’s gritty, grind-y bluegrass. With a lot of soul.

Tammy: Think about the Rolling Stones if they were to play with bluegrass instruments. That’s us.

Mike: With a blues/rock ‘n’ roll singer. … It’s intense! I’m tired after our set. It’s a workout. We keep the emotion and the intensity going quite a bit, but we let up occasionally and do a nice song.

On this record, you do have that slower moment on “I Choose You,” which brings out another side of the band.

Tammy: Yeah, we’ve always had a song or two like that. On the first record, “Heaven Sent” has always been one of our most-requested and popular songs, and it has that great, easy, rolling feel to it. We call it the hippie dance. And when Thomm Jutz and I wrote “I Choose You,” that was definitely musically where I wanted to go with that, to have that feel to it. But it’s still a very serious lyric, even though it has a positive message, in a way. It has a lot of depth and meaning to it.

Richard, do you have a favorite track on this album?

Richard: Umm… “Forgive.”

What do you like about that one?

Richard: I like what I played on it. [All laugh]

Tammy: See, it’s all about the banjo! We joke about it but people love the banjo!

Mike: It’s got a great groove.

Brent: It’s one of my favorite songs too.

Kelvin: It’s funky. It’s like “Bad For You” is rock ‘n’ roll and “Forgive” is funky!

Kelvin, what were you listening to about three years ago, before joining the band?

Kelvin: Three years ago I was on a really big Cinderella kick. [All laugh] I’m still on the kick. I still listen to mainly rock ‘n’ roll when it’s just me in my truck, driving for hours on end.

Did the band prepare you for the honesty of bluegrass fans, and how they’ll tell you what they think?

Kelvin: I was ready for it before I started! I knew how much of a following they had. I know how much people loved Gary. I know how much people loved Chris. And I was ready for it – I prepared myself for people saying, “This guy sucks. You need to get somebody else.” [I’ve heard that] twice, I think, the whole time I’ve been with the band. It’s been great — because I was expecting it at every show!

Tammy, do you have young women coming up and telling how cool it is to see a woman on stage?

Tammy: Yeah, it’s really awesome and I appreciate it a lot. Because when I was growing up there were very few women playing, and the ones that did were usually bass players. Mama might be back there thumping on the bass or whatever. There were very few women role models for me, of that generation. There were a couple — I remember Lynn Morris was playing and Laurie Lewis was playing a few years ahead of me in those circles. Not many in the country world. I was a huge Mother Maybelle fan and part of that was because she played the guitar. That was fascinating for me as a kid.

And now in the generation after me, there’s just unbelievably talented women – not just singers, but instrumentalists. It’s phenomenal, the jump from mine and Alison Brown’s ages, to Sierra Hull, who is a genius on the mandolin, and Kimber Ludiker and all the Della Mae girls we love, and Molly Tuttle is absolutely slaying it on guitar. Sara Watkins, I’m With Her, Sarah Jarosz … it’s just on and on and on. If I in any way influenced any of those players, I am deeply honored.

What would you want bluegrass fans to know about this new record?

Tammy: We’re excited this year to get out and we’ll be playing a lot of different kinds of venues. We don’t play that many traditional bluegrass festivals anymore, but it’s my hope that people hear the music and still see the thread that’s in there. The subject matter that we choose to sing about is not as cleaned up as some other stuff, but to me it’s just another facet of the music, and I think we’re hopefully carrying it forward and carrying a torch.

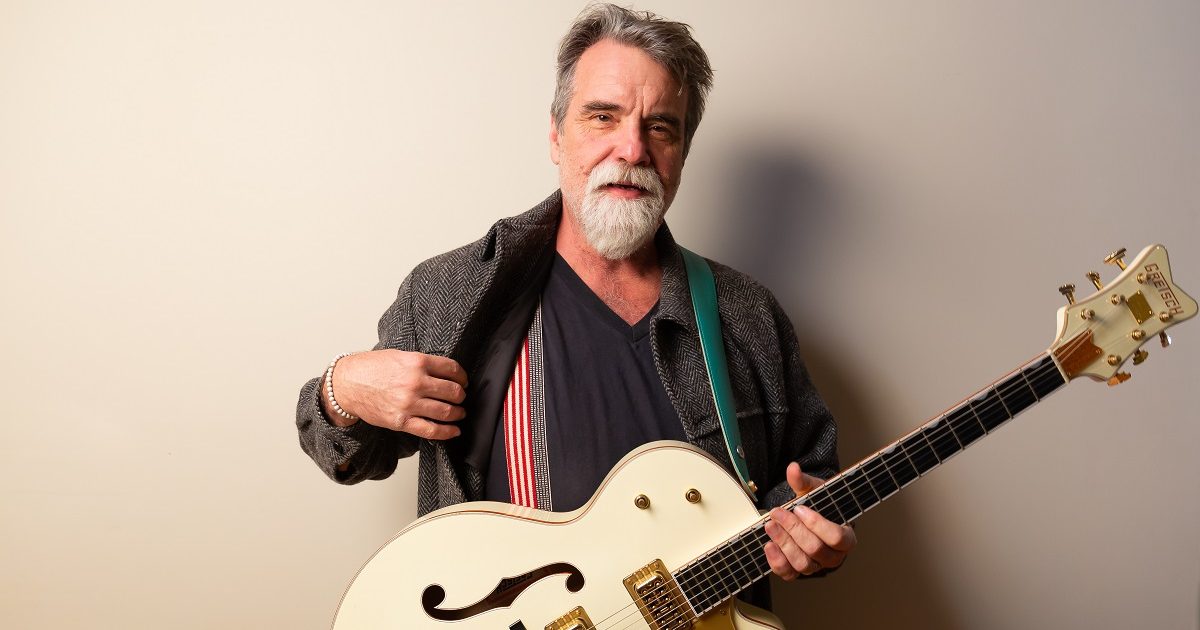

Photo credit: Anthony Scarlatti