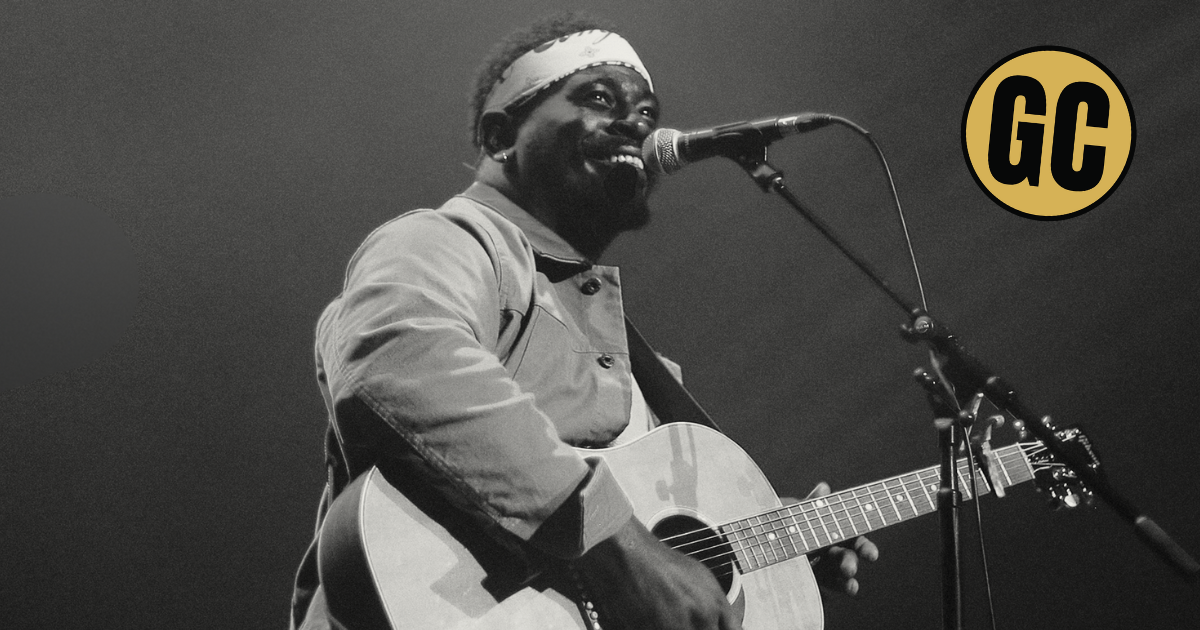

To say Kashus Culpepper’s life has changed over the last five years is an understatement. A former state champion wrestler, firefighter, and EMT, the Alabama native developed a raspy, smoke-and-voodoo vocal while stationed in Spain with the U.S. Navy in 2020, forced to pass the pandemic in his bunk. Since then, he’s knocked over one milestone after another.

With a distinctive mix of country, blues, Southern rock, and soul, the 27-year-old cites Robert Johnson, Bill Withers, and Hank Williams as inspirations and is now bringing his roots-renegade instincts to mainstream fans. Despite only releasing his first official track in June of 2024, the music industry short-timer has earned big-time appreciation.

That includes the respect of heroes like Elton John and John Mayer, a Grand Ole Opry debut, tour dates around the country, and inclusion on 2025 “artist-to-watch” lists at GRAMMY.com, Apple, Billboard, Pandora, and more. Culpepper just finished a run of dates with Leon Bridges and he’ll hit the road with Whiskey Myers in June before joining tours by Sierra Ferrell, Darius Rucker, and others later on in the summer. It would all be overwhelming, if he had time to think about it.

“I’ve just been taking it day by day,” Culpepper tells Good Country with a hearty laugh, waiting to perform at a community festival in Arkansas last month. “I think that’s the best course of action. Don’t think too far in the future and just take each show, each writing session, each recording session one at a time. Just pray everything works out and keep going. … Because when things started happening, I was like, ‘Oh, snap.’”

We wanted to get to know Culpepper before anything else “happens,” and figure out what’s fueling the hype. As it turns out, this all-natural talent is just going with the flow.

I read that you didn’t even start playing guitar until you were in Spain for the Navy, right? What made you want to do that?

Kashus Culpepper: Yeah, in Spain we got shut down and I didn’t have nothing else to do, man. I mean, literally I was bored out my mind. It’s a different type of boredom, because during COVID you couldn’t do nothing. It’s not like you can just go outside or go to a bar or hang with your friends. We couldn’t do nothing. So this was a weird point in my life and my buddy had a guitar in the barracks. I was like, “Well, this is a perfect time. I literally have nothing to do.” I just went on YouTube and looked up covers I wanted to learn. Music has always been something I go back to whenever life is hard. So I resorted back to music and that ended up leading me to learn guitar, eventually learn to write songs.

Thank God for YouTube, huh?

Shout out Marty Schwartz!

You seem to have a lot of diverse tastes, but that bluesy, soulful country thing – why did that speak to you?

I think maybe that’s just my music taste. My first taste of music was gospel, and I’m from Southern Alabama, so gospel there, it’s really rootsy already. It already sounds like a folk song. And the way they sing it sounds so bluesy, like old Son House type of vibes. From there I got into blues music outside of church. I got into country music and R&B and folk music a little. I’m all over the place when I listen to music. I can go from Allman Brothers to a Conway Twitty song really quick.

But I know you like John Mayer and all that stuff, too, right?

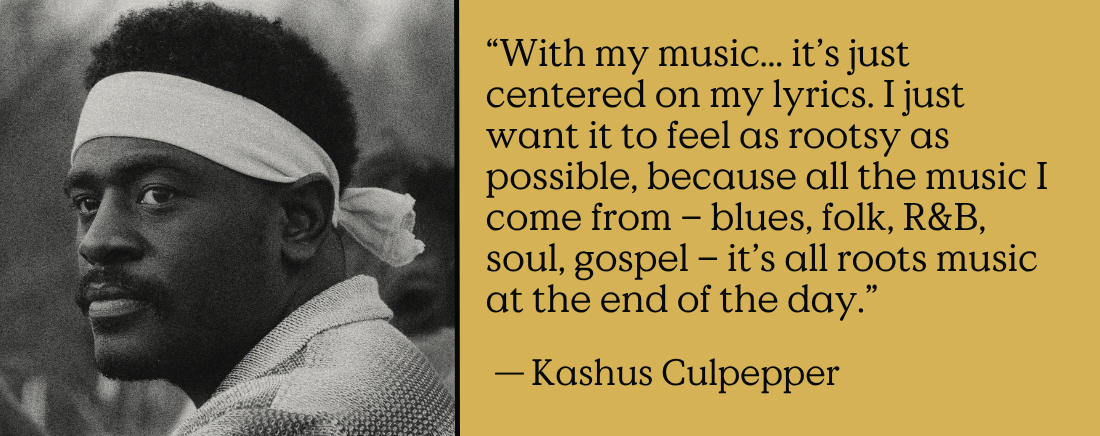

Yeah, yeah. I mean, I love so many of those rock artists, ZZ Top, Led Zeppelin, Skynyrd. People ask me all the time my influence and I’m just like, “Bro, it’s so hard to name everybody.” John Mayer was a huge thing for me. Recently I went back to Norah Jones, I’m like, “Man, I used to love this record.” But with my music, at the end of the day, it’s just centered on my lyrics. I just want it to feel as rootsy as possible, because all the music I come from – blues, folk, R&B, soul, gospel – it’s all roots music at the end of the day.

Your voice is so good at expressing these really raw emotional states, I think. Is that how you are naturally? Or does that only come out in your music?

Most of the time? Honestly man, it’s just with the music. It’s hard to open up to the people. I think for me music has been great, just to express how I actually feel through my singing and my lyrics. I don’t usually just tell people.

So you’re from Alabama. After the Navy, did you go home and keep playing?

I got out the Navy in 2022 and by that point I already had gigs booked on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. I was booked at all these casinos, all these bars. I was booked out for a year in advance. I got out and went straight to full-time doing cover band shows pretty much for another year, until I literally couldn’t take any more of it. Then that’s when I decided I really want to write songs. Literally, I decided “I’m going to move back home to save as much money as I can and move to Nashville.” I was home for maybe a week or two and posting a lot on TikTok and I remember I was in my mom’s living room. I posted a TikTok, I went out because I had an interview for a job, I got back home, and it had reached 100,000 views. From there it was just, “Oh, snap. It’s going on.”

@kashculpeppermusic Replying to @Casey Wayne One week till “Man of His Word” drops! Appreciating all the support on this one❤️ Pre-save link in bio🔥 #country #singersongwriter #original #kashusculpepper #newmusic #livemusic #countrymusic #countrymusiclover #tour #soul #newcountry ♬ original sound – Kashus Culpepper

That’s awesome. Congratulations on how that all turned out. I think one reason for it might be that your music seems so unconventional, almost untamed. Maybe because you did it on your own? Do you feel like fans are hungry for that?

I think so. We talked about John Mayer. John Mayer is kind of like that. He’s all over the place. Sometimes he’ll do a blues song and then straight up pop, and then an R&B song with Leon Bridges. I think people just love that from artists. Artists just being artists. Just do whatever the song feels like. That’s how I feel with songs.

“A Man of His Word” is super soulful, with lots of that gospel influence and a big raspy vocal. Tell me about being the man a girl deserves. Where’s that theme coming from?

I wrote that song with Natalie Hemby and at the time we was just talking about life. The song is from a perspective of a guy looking into a girl and she’s going through hardships, because she don’t have a man of his word. She’s drinking a lot, doing a whole bunch of stuff. The song has a lot of me in it. I grew up with a single mother and you don’t know how those things can affect you without having somebody in your life you can trust. You get the feeling you can’t really trust nobody, because that’s not part of your life, and that leads to mental health problems or substance abuse. You don’t even notice it at the time, until you look back and you’re like, “Dang, that’s why I feel that way.”

After that comes “Broken Wing Bird” with Sierra Ferrell and it’s on the opposite end of the spectrum. Very threadbare and folky, right?

Oh man. So I’m a huge fan of Willie Nelson. One of my favorite songs is “Funny How Time Slips Away” – I just love so much the crooner era that he was doing – and I wanted a song that felt like that.

I wrote the song about somebody that’s not really good for you and you just keep taking ‘em back regardless, because you love them and no matter what they do, you’re always going to. So she’s like my broken-winged bird – no matter what she does, she’s flying back and I’m always going to help her out and then she’ll probably be on her way again.

It’s been good getting to know you a little. Big picture, what do you hope people take away from your music?

I think overall, I hope they can see I’m just an artist trying to express the way I see things, and I hope in some way they can find music that can fit every part of their life. Whether they’re trying to have a good time out partying, or if they want to soak into the sadness of a lover they lost, I just hope my music can fit some aspect of their life. And I hope they can enjoy it.

Photo Credit: Cole Calfee

Sign up here to receive Good Country’s email newsletter direct to your inbox.