Wherever you are on this wintry week, we hope our collection of roots music premieres warms you all the way up. We expect it will!

In this edition of our premiere roundup, don’t miss a brand new track from stupendous string trio, The Devil Makes Three, who debuted “Ghosts Are Weak” from their upcoming album on Wednesday on BGS. Plus, there’s straight-ahead bluegrass to be found, too, from Tyler Grant, who pays homage to a towering train bridge on “Goat Canyon Trestle.”

Singer-songwriter Bre Kennedy has reimagined “Before I Have a Daughter,” a song co-written with Lori McKenna about breaking generational cycles, healing, and motherhood. (A theme shared with another premiere this week.) And, Tobacco & Rose repurpose a love song infused with a Buddhist twist with their new track, “Tara.”

In the mood for some music videos? Catch Leslie Jordan’s new video for a Sarah McCracken co-write, “The Fight,” that also grapples with parenthood, discipline, and family. And, the sensational Max McNown brings us the video for the title track for his brand new album, Night Diving, which releases today.

Just in time to shepherd out the once-in-a-lifetime blizzards across the Deep South, Miss Tess showcases her music video for “Louisiana,” a centerpiece of her upcoming album, Cher Rêve. Then Sarah Quintana, who calls New Orleans home, brings us down the road to the Big Easy with an artful music video made with Kat Sotelo for the title track of her soon-to-be-released project, BABY DON’T.

It’s all right here on BGS and, you know the drill – You Gotta Hear This!

The Devil Makes Three, “Ghosts Are Weak”

Artist: The Devil Makes Three

Hometown: Santa Cruz, California

Song: “Ghosts Are Weak”

Album: Spirits

Release Date: January 22, 2025 (single); February 28, 2025 (album)

Label: New West Records

In Their Words: “‘Ghosts Are Weak’ is about breaking free from destructive habits and patterns. It reflects on how leaving behind a substance or lifestyle often comes with losing certain friends along the way…” – Pete Bernhard

Tyler Grant, “Goat Canyon Trestle”

Artist: Tyler Grant

Hometown: Boulder, Colorado

Song: “Goat Canyon Trestle”

Album: Flatpicker

Release Date: January 24, 2025 (single); March 28, 2025 (album)

Label: Grant Central Records

In Their Words: “The largest wooden trestle ever built still stands in the Mojave Desert of eastern San Diego County. I wrote this uptempo bluegrass song to tell the story of the trestle and the ‘Impossible Railroad,’ which was conceived by sugar and shipping magnate John D. Spreckels in 1906 and completed in 1919. History songs are tricky and I am very proud of this one. It will tickle the ears of any enthusiast of the classic railroad songs. I furnish some Doc Watson-style flatpicking and Michael Daves delivers on the hot tenor vocal part. The moral of the story is, if you take on the desert, it will always win.” – Tyler Grant

Track Credits:

Tyler Grant – Guitar, lead vocal

Andy Thorn – Banjo

Adrian “Ace” Engfer – Bass

Dylan McCarthy – Mandolin

Andy Reiner – Violin

Michael Daves – Harmony vocal

Leslie Jordan, “The Fight”

Artist: Leslie Jordan

Hometown: Johnson City, Tennessee

Song: “The Fight”

Album: The Agonist

Release Date: April 25, 2025

In Their Words: “‘The Fight’ was written with Sandra McCracken on her back porch in September of 2023. When I read the piece that my grandfather wrote with the same title, I knew I had to save it for my co-write with Sandra. I have long admired Sandra’s ability to tell a story in her songs with honesty and raw vulnerability. I knew she could help me capture the true intention of this piece. It is heartbreaking. Gut-wrenching. A mother’s internal dialogue after she loses control and hits her son. We sat for a while and chatted through what we thought was really happening in the story, how it made us feel, and then I started playing the chord progression you hear. The story my grandfather wrote begins with these two lines:

‘The rebellion was over, and she had sent him to wash-up.

There comes a time when children must be made to realize limitations and authority.’

“Sandra immediately started scribbling in her notebook and turned it around to show me.

‘The rebellion was over

She sent him to wash his hands

She tried to reason with him

But he could not understand

There comes a time when you find the limit’

“I started singing the words along to the chords and it felt like we had caught lightning in a bottle. I was also very excited to have my friend Brittney Spencer lend her incredible vocals on this song! When she heard it, she immediately had an idea that would lift the chorus. She really brought the song to another level.” – Leslie Jordan

Track Credits:

Leslie Jordan – Acoustic guitar, vocals

Brittney Spencer – BGVs

Kenneth Pattengale – Guitar

Harrison Whitford – Resonator guitar

Daniel Rhine – Upright bass

Joachim Cooder – Drums, percussion

Evan Vidar – Pump organ

Video Credit: By Jake Dahm. Edited by Leslie Jordan.

Bre Kennedy, “Before I Have A Daughter” (featuring Lori McKenna)

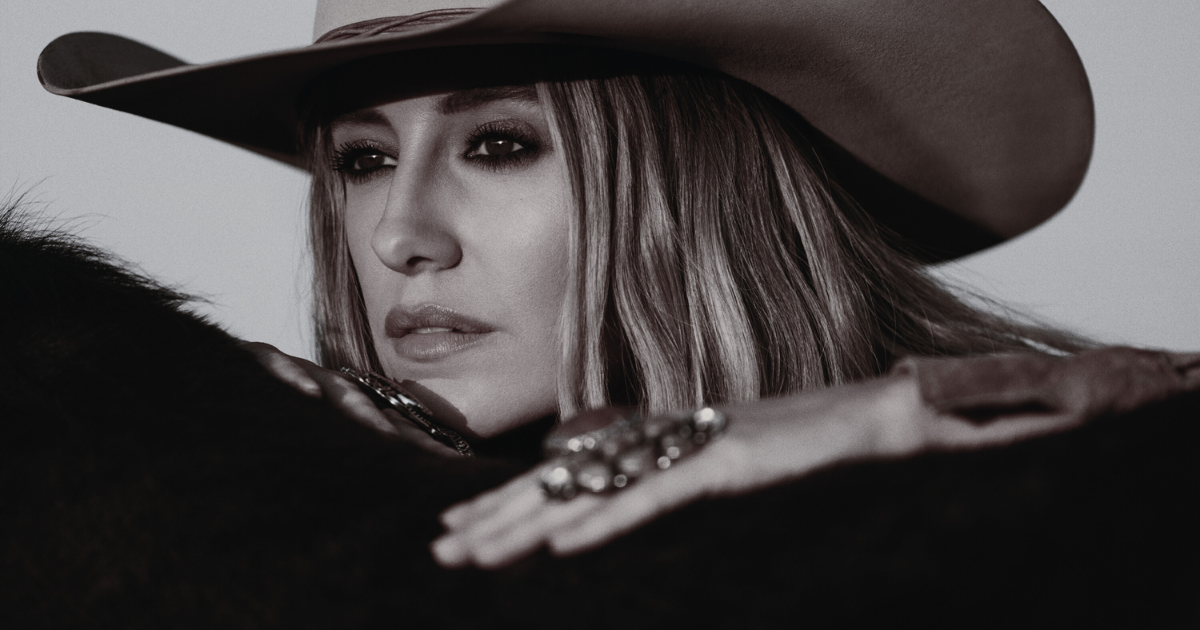

Artist: Bre Kennedy

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Before I Have a Daughter” featuring Lori McKenna

Release Date: January 24, 2025

Label: Nettwerk Music Group

In Their Words: “I am so excited to share this version of my song ‘Before I Have a Daughter’ with the one and only Lori McKenna. I wrote this song with Lori a few years back after small talk that led to a conversation about me not knowing my mother, who struggled with addiction as I grew up, and wanting to get to know her and heal with her before I have a daughter. Writing this song was the beginning of a healing journey with not only my mother, but with myself. [It’s] how I have learned to have grace and appreciation for my journey, as well as hers. This song continues to grow with me in real time and I am so honored I get to share this version with Lori with you all from where I am on my journey now.” – Bre Kennedy

Max McNown, “Night Diving”

Artist: Max McNown

Hometown: Bend, Oregon

Song: “Night Diving”

Album: Night Diving

Release Date: January 24, 2025

Label: Fugitive Recordings x The Orchard

In Their Words: “We stepped into the writing room and Erin [McCarley] asked, ‘What’s something in your life that you keep fighting and can’t seem to overcome?’ ‘Night Diving’ became the answer to that question – it’s a song that addresses addiction and I think it’ll resonate with people on a lot of different levels. The ‘Night Diving’ song and video contain the deepest waters of symbolism I’ve created to date.” – Max McNown

Track Credits:

Jedd Hughes – Electric guitar

Todd Lombardo – Acoustic guitar, mandolin, additional electric guitar

Jamie Kenney – Bass, acoustic guitars, additional electric guitars, drum programming

Aaron Sterling –Drums

Max McNown – Lead vocals, background vocals

Miss Tess, “Louisiana”

Artist: Miss Tess

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Song: “Louisiana”

Album: Cher Rêve

Release Date: January 24, 2025 (single); February 7, 2025 (album)

In Their Words: “‘Louisiana’ was the first song inspiration for my new album Cher Rêve, coming out February 7. It was deep in the pandemic and I had reached a point where I was really missing traveling, friends, live music, and dancing. I became fixated on my memories of basking in the Cajun culture of South Louisiana (Lafayette & Eunice, mainly during the Blackpot Festival and music camp), and started to write a song about it.

“My excellent co-writer friend and fellow Blackpot visitor, Maya de Vitry, helped me work on it for about six hours one day while she was house-sitting. Since it was a challenging time to hang out with people in person, we finished it over the next month via email. It is one of my favorite songs on the album and really sums up my feelings and nostalgia for being down there, playing and enjoying music beneath the tall Louisiana pines. I am thankful this recording includes the talents of so many amazing Lafayette-area musicians, including Joel Savoy (fiddle + studio engineer), Trey Boudreaux (bass), and our dear friend Chris Stafford (Wurlitzer), who passed away tragically this past May.” – Miss Tess

Track Credits:

Thomas Bryan Eaton – Electric guitar, vocals

Joel Savoy – Fiddle

Miss Tess – Vocals, guitar

Kelli Jones – Vocals

Chris Stafford – Wurlitzer

Trey Boudreaux – Bass

Matt Meyer – Drums

Sarah Quintana, “baby, don’t”

Artist: Sarah Quintana

Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana

Song: “baby, don’t”

Album: BABY DON’T

Release Date: January 24, 2025 (single); March 28, 2025 (album)

In Their Words: “Kat Sotelo is the amazing performance artist and videographer behind this video. She designed and executed the concept, built the set, and asked the band to wear blue jeans. We wanted the first single to feel like something off The Ed Sullivan Show in the ’60s with a live performance lip-sync and vintage transitions. Silly moments of stop-motion animation flaunt Adrienne Battistella’s stunning band photos.

“I love Kat Sotelo’s work. She is a longtime friend and collaborator and my muse. She is a lovely human, creative powerhouse and inspiration to us all! She and I have been working together since my first project, Mama Mississippi, in 2012. Thanks for this adorable video, Kat!” – Sarah Quintana

Track Credits:

Cello: Chris Beroes-Haigis – Cello

Drums: Rose Cangelosi – Drums

Saxophone: Rex Gregory – Saxophone

Sousaphone: Jason Jurzak – Sousaphone

Recorded by Justin Tockett at Dockside Studios

Video Credit: Video and set design by Kat Sotelo, photography by Adrienne Battistella.

Tobacco & Rose, “Tara”

Artist: Tobacco & Rose

Hometown: Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

Song: “Tara”

Release Date: January 31, 2025 (single)

In Their Words: “‘Tara’ is a repurposed love song. The initial melody and lyrics were inspired by a crush that subsided as quickly as it appeared, but I was inspired to revive the song after following along to some guided Tara meditations. The Buddhist deity, Tara, is known for her compassion, but also for her encouragement to action. So I dedicate it to her, and, in fact, the writing of this song spurred into action the completion of my record, as it was the last song I wrote for it, and a standout track at that. I love this song, in part for the unusual wide guitar voicings that I got from my viola studies as a teenager, and for the melody that soars into head voice at the end of the chorus. And lyrically, I treat this song as a Buddhist-themed reminder for myself to stay awake and aware, and to treat all challenges, afflictions, and aversions as opportunities to get better at human being.” – Richard Moody

Track Credits:

Richard Moody – Guitar, vocals, strings, keyboards

Joey Smith – Bass

Photo Credit: Max McNown by Nate Griffin; Miss Tess by Jo Vidrine.