We are in a moment of extreme distress. Especially, but not limited to, the formal politics of America’s dying empire. Living in its wake, it’s easy to collapse into hopelessness. Hopelessness seems reasonable, considering the criminalization of trans voices, or ICE raids, or the tariffs that wipe out hard earned income, or climate change, or any of the other myriad disasters we are in the middle of. There has to be some way forward – a full understanding of how bad the situation currently is, but also that there might be a small amount of hope; that it has been worse than this, but it has also been better.

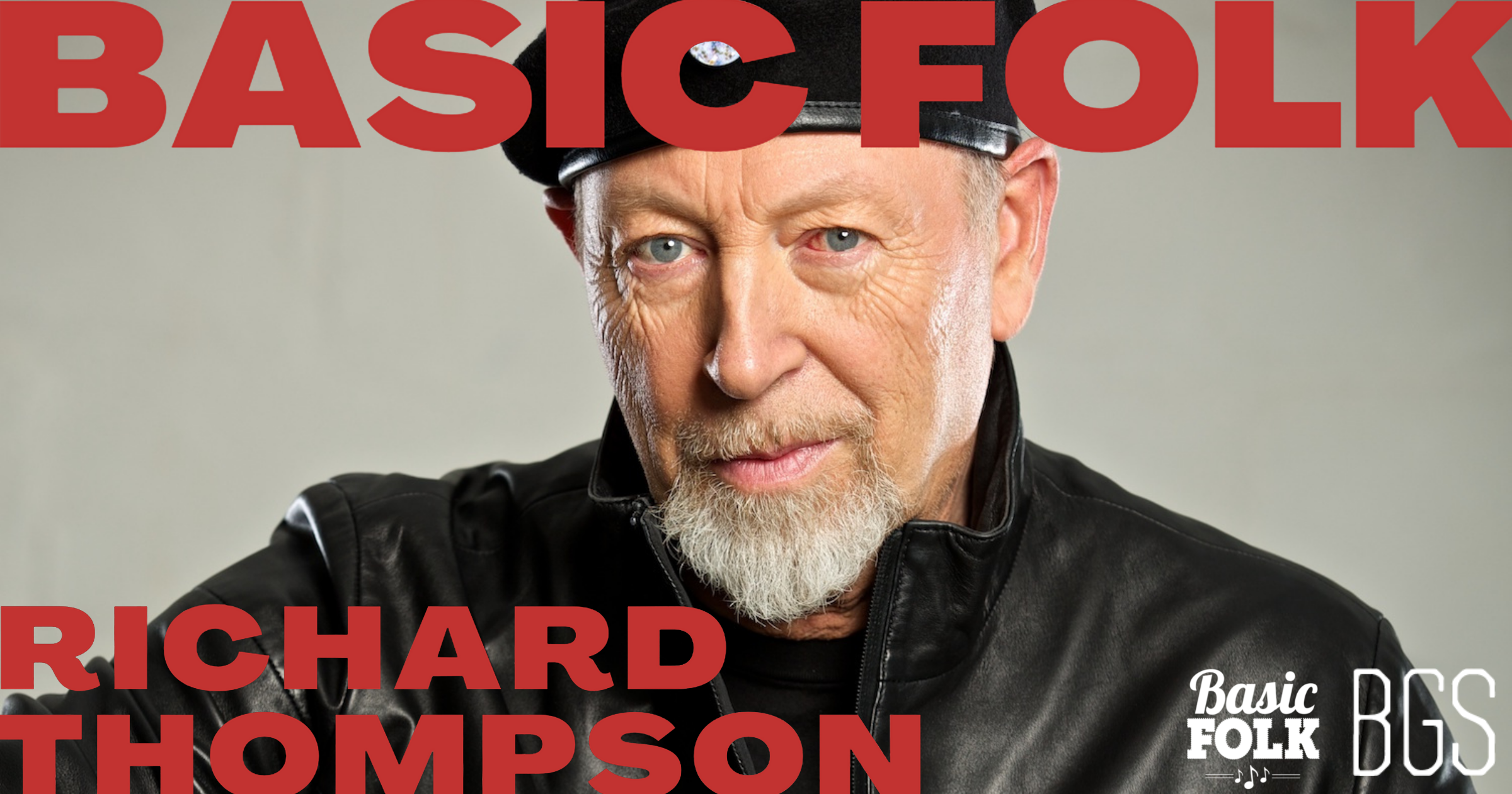

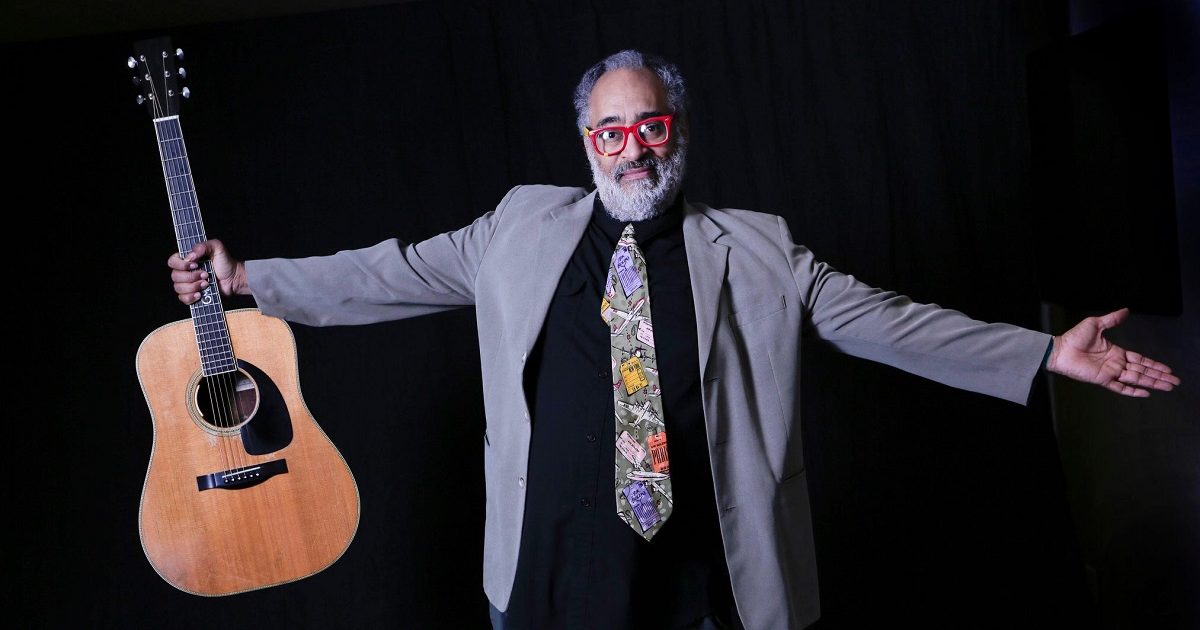

Willi Carlisle released an album of traditional songs, called The Magnolia Sessions, in December 2024 and will release Winged Victory June 27 via Signature Sounds. Winged Victory includes original songs and covers of Utah Phillips, Richard Thompson, and Patrick Haggerty, among others. These songs are about the delicate negotiation between historical understandings, current realities, and the possibility of a progressive future; about carving out small moments of pleasure against melancholy; of building a small paradise against these impending crises.

I reached Willi Carlisle by phone on Good Friday, the saddest day of the Christian calendar. On the first Good Friday, no one thought Christ would return. I have not been a believer for a while, but I remember sermons in college which warned against racing through Friday to get to the hope of Sunday. So when I call this album a hopeful one, it is hopeful with a full acknowledgement that it might not get better. The work needs to be done with the assumption that there is no intervention, divine or otherwise.

When asking Carlisle about optimism, or about hope, he makes his choices sound purposeful, mentioning that he had been wanting to make this kind of album for more than a decade and that these two albums are “more just like musical moments that continue to say the things I want to say, as opposed to saying the things that I want to get off my chest.” This is not a manifesting energy, or an optimism despite all odds, but one which is well earned after decades of performing.

Those decades of performance tile with decades of listening, each working together mutually. Winged Victory has several moments which cross cosmic time – decades or centuries – looking backwards or seeing what is possible in the futures of our children’s children’s generations. The collection begins, for example, with the Utah Phillips standard, “We Have Fed You All for 1000 Years.” Its chorus states baldly:

Go reckon our dead by the forges red

And the factories where we spin.

If blood be the price of your cursed wealth,

Good God! We have paid it in!

This album is one of reckoning, of refusing the standard moments. In the original song, “The Cottonwood Tree,” a slow waltz, Carlisle talks about a “place where nobody lives, and everyone is free.” He is singing in first person while he plays a concertina, mentioning how he is part of nature now and how he will be part of nature in his own rotting. He is happy to die trusting people, but even after dies, even when he is buried under “the cottonwood trees,” he will be heard.

He concludes the song, believing that he will meet his friends six feet under the cottonwood tree. In a subtle moment, his friends are “the tall grasses rustling between his ears,” or the forget-me-nots in a parking lot, and maybe even other humans. Here time collapses, between the immediacy of the moment and the length it takes a body to absorb fully into those cottonwood trees.

Carlisle’s album of traditional songs, The Magnolia Sessions, has moments of this cosmic time as well – a much eerier version of “Leatherwing Bat” than the one made famous on Peter, Paul and Mary’s children’s album, as well as the last song, a version of “Jubilee,” a moment which reminds us again that the joy will come, after working and waiting.

Conversation between original tracks and new work is central to Carlisle’s practice. His reckoning, which occurs over and over again, is also about the complex matrix of listening and performing other people’s songs. When asked about the covers, he talks about working together – that he had a “strong relationship to the material…”

“I see my whole project in folk music is hearing history with all of its interpretations, its historicity, back to the lives of actual human beings. It’s time to take off the cowboy hat and put on the work gloves.”

The strength of the relationships between material, is partly due to how the original songs on this album work in conjunction with the old songs. For example, how the waltz of “The Cottonwood Tree” leads into the harder, faster waltz of the Patrick Haggerty-penned “Cryin’ These Cocksucking Tears.” That Carlisle includes a Patrick Haggerty song at all is remarkable, even more so that he makes it full of joy and he considers it as part of the tradition of folk and country music. It’s a cult song in queer folk circles – the mainstreaming of this work is a foregrounding of queer desire, another tradition and another culture. Carlisle sings it with horns and an accordion which sounds like a circus calliope (between this and Lucy Dacus’ “Calliope Prelude,” the instrument is having a moment).

Collapsing of time can again be seen in his version of Richard Thompson’s “Beeswing.” Also running a little quicker than the original, it’s a song about lovers who cannot be kept and immediacy about “the price you pay for the chains you refuse.” But the next song, “Big Butt Billy” – a comic riff on possibly hooking up with a non-binary server at a diner in the midwest – makes other arguments, models other kinds of hope (for an immediate pleasure).

Other versions of “Beeswing,” meanwhile, take the side of the narrator and have a misogynist tinge against the person who roams. Having these two songs back to back argues in favor of roaming and typifies desire as a kind of roaming – Haggerty wants, the Romany wants, the server wants, and at the risk of thinking he might be a little autobiographical, Willi wants. Throughout these two albums, the hunger is palpable.

Roaming is central to Carlisle’s music, not only on this album, but as a theme. Roaming through time and space, through the cosmos, and on the very real roads of California, Texas, or Wisconsin. The first thing that Carlisle and I talked about was BBQ and about Kansas City, where he is staying on Good Friday when we connect. That could be seen as a kind of metaphor – having strong feelings about a very local meat & three and about the history of a song that is brand new; having thoughts about the place where he is landing and a song that is centuries old.

Roaming is a way through this mess, through catastrophe and disaster as a way of finding community, against despair while not naively thinking things will get better without labor. This pattern of Carlisle’s interpretive skill is top notch throughout both of these albums, because of that curious hunger, that roaming, and that possibility of a way forward, even in the darkest era.

The last question I asked Carlisle was about theater – he had worked at Fringe shows in his 20s. He said that he wanted to direct or act again, especially Brecht. I keep returning to Brecht’s “Motto,” which reads in its entirety:

In the dark times, will there also be singing?

Yes, there will also be singing.

About the dark times.

This poem was the epigraph to a book written when Brecht had moved to Denmark, escaping German fascism.

Winged Victory reveals there is great beauty in darkness, that singing itself is an act of optimism, and that exile creates its own narratives. Therein, Carlisle has found a way of singing through dark times.

All photos: Whit Stone