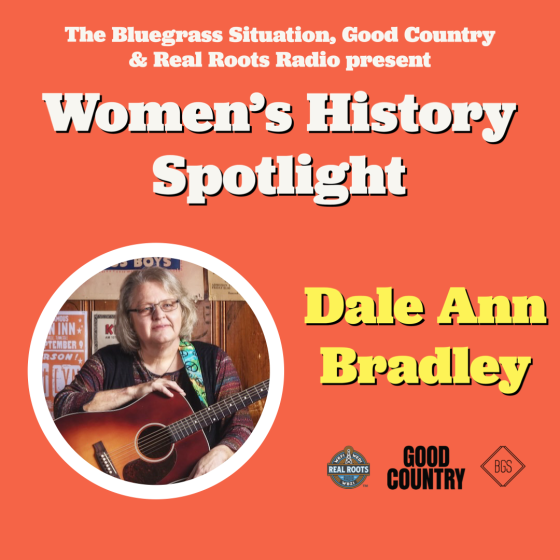

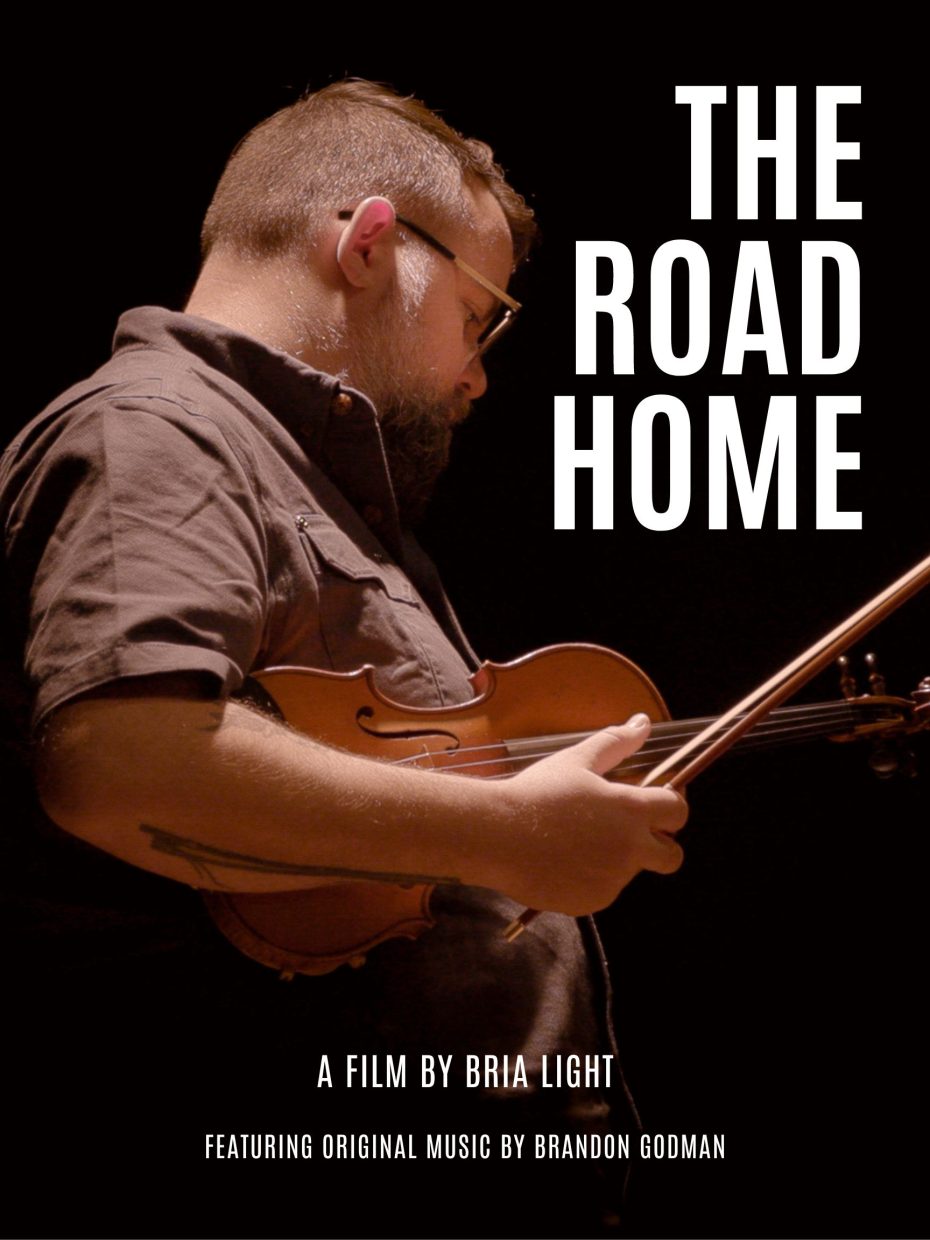

Bluegrass and country fans may recognize Kentucky-born, San Francisco-based fiddler Brandon Godman from touring, recording, and performing with folks like Dale Ann Bradley, Laurie Lewis, Jon Pardi, the Band Perry, the Music City Doughboys, and many more. He’s also an accomplished business owner and luthier, helming two fiddle repair and retail shops based in Nashville (The Violin Shop) and the Bay Area (The Fiddle Mercantile.) In addition, Godman helped found Bluegrass Pride and was instrumental in organizing the non-profit association’s float and marching contingent that won the coveted “Best Overall” ribbon from the 2017 SF Pride Parade.

Godman has played fiddle his entire life, beginning on the instrument as a young child in Northern Kentucky. His skills span old-time, bluegrass, western swing, country, contest fiddle, and beyond, and his career, by necessity often, has been remarkably varied, boasting stories of success, trials, tribulations, and highs and lows beyond his years. Now, filmmaker Bria Light has crafted a remarkable, heartfelt, and stunning documentary short all about Godman and his journey on and with the fiddle.

Shot and crafted in 2022 and 2023 as Light’s thesis film at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, The Road Home is an intimate and gorgeous look at Godman and his relationship with his instrument, his career path, and his rural home in Kentucky. The film includes lovely original music – much drawn from Godman’s acclaimed 2024 solo album, I Heard the Morgan Bell – that offers many varied samples of his expansive skillset on fiddle throughout, a perfect score and soundtrack for the 20 minute-plus documentary. Together, Light and Godman travel from California to Kentucky, visit with Godman’s family, share old memories and stories, and examine the complications and intricacies of family and community, the transient, intangible nature of “home,” and the pains and reliefs of leaving and returning.

Now, for the first time, The Road Home is available to screen online, right here on BGS and on YouTube. (Watch below.)

Light has a deft and artful touch as a filmmaker and director, utilizing the fiddle and Godman’s original compositions as an enormous character in these narratives, propelling the story forward and entrancing viewers with the sights, sounds, textures, and mythos of Northern Kentucky – as could only be delivered by a musician and creative like Godman. The end result is moving and illuminating, subverting expectations of the region, the instrument, the genres we associate with the fiddle, and the communities we expect – or don’t expect – to love these traditions and the people who keep them alive.

We spoke to Light via email about the film, its conception and making, and the twists and turns along the way that led Light and Godman to this stellar piece of visual, aural, and narrative storytelling.

Let’s begin by going back to the beginning. Can you tell us a bit of the story of how this film project came to be? What inspired you and how did you get connected with Brandon?

Bria Light: I made this film for my thesis film in the documentary film program at UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism and when it came time to look for a story that I would be spending all year working on, I knew I wanted a story that was music-related. But I also wanted to find a story that revealed something deeper about how music can help us find our way through the sometimes fraught path of being human. I eventually got connected with Brandon, who agreed to let me into his life and tell me this slice of his story.

This film tells such an expansive story in a relatively short amount of time. What was it like trying to condense such an interesting and often complicated narrative into this short film “package”?

I’ve sometimes used the metaphor that making a film feels like having the vast expanse and depth of the ocean stretching out before you and your job is to chart the best course from continent to continent. It can feel overwhelming! At every turn there are not only creative decisions to be made (What part of this person’s complex life do I focus on? Do I shoot this scene? Do I interview that person?), but also ethical ones (Who is affected by telling this story and how? Should I or should I not reveal someone’s identity? What impact am I hoping for this film to have and how is that best served?).

While you’re finding and crafting the story, it’s not always self-evident what the best, most meaningful storyline is and you want to explore a million different possible paths. You end up with hours and hours of footage (the ocean) that you have to fully explore to find the best course. And the thing is, you have to try things out to see if they work in a movie and until that golden moment where something works, it, well, doesn’t work. So it is a process of months – or years for feature docs – of trial and error, during much of which you suspect you might be terribly lost at sea and had no business becoming a sailor in the first place, to follow the metaphor… until one fine day you’re like, “Land ho!” and things start coming together and you can sleep again at night. [Laughs]

I feel like you let the music itself, and the tradition of fiddle music and roots music, do a lot of the storytelling here. What is it like translating music to a visual media like film in this way and leveraging it to help advance your narrative?

Absolutely. One of the key elements of my vision of the film from the beginning was to leverage the richness of this musical tradition and Brandon’s music within that to assist in telling his personal story. In fact, I pictured the music almost as a character itself. Music, of course, is a storyteller, even when it doesn’t have lyrics. So thinking of the music almost like the narrator of the story felt very natural.

Of course, Brandon creating his album of original tunes, I Heard The Morgan Bell, is part of the film’s narrative as well, so it all tied together organically. Additionally, since part of the film delves into the past and the creation of the album was the part of the story that was unfolding in the present, it helped provide a narrative thread to follow and to tie Brandon’s musical and personal evolution together from his past to his present.

Can you tell us a bit about what it was like traveling to Kentucky with Brandon?

It was very, very cold! Our trip to Kentucky took place over Christmas week and it just so happened to be during a cold snap that swept the entire country. It was in the single digits temperature-wise, in the negatives with wind chill, and the roads were covered in thick ice. I had envisioned going there and shooting scenes on the family farm with golden winter light sparkling in the crisp air, etc., and instead there was roaring wind so bitterly cold that you could barely be outside for two minutes before your fingers were completely numb. At one point, my camera was having some issues because it was so cold! But of course we filmed mostly inside and Brandon’s family was so warm and welcoming. I ate a copious amount of Mamaw’s famous chocolate peanut butter squares!

The music of the film is so stunning, and some of the selections went on to be included on Brandon’s 2024 album, which you mentioned already, I Heard the Morgan Bell – it was one of our favorite bluegrass albums of last year. Was there a “music supervision” process for the film? Did you leave it up to Brandon? What was it like collaborating on what would become the soundtrack and soundbed for your visuals?

Brandon was so generous in granting me permission to select music from his album, which was still in process, to use for the film. Through the course of our many hours of conversation over the year, he told me many of the stories behind the songs, of the inspiration and ideas that led to their creation. So I used that, along with the general feel and mood of the tune, to inform my choices as to which pieces to include where. Normally, you’re right, there would be a music supervision process, but in this case I had the privilege of working directly with Brandon, who was essentially also the film’s composer!

Do you have a favorite moment in the film? Or from the process of crafting it?

Hmm, there are so many memories attached to the creation of this film! I loved filming and editing the “Morgan Bell” scene in the church. The music is so gorgeous and I knew I would love filming in low light with stained glass church windows as the container for that wordless song that expresses so much emotion.

I also loved the moment in the editing process where I found the old footage of Brandon as a young teen on a local TV show. In Kentucky, his parents had given me a paper bag full of photo albums and old VHS tapes of Brandon at fiddling contests and other things to go through and see what I could use. Late one night, after a full day on campus, I headed back to the edit rooms in the journalism school to continue digitizing and going through the old VHS tapes. I got to one tape, began watching it, and it seemed to be all recorded re-runs of Days of Our Lives. After fast-fowarding through so many episodes of Days of Our Lives, I was wondering if that tape had been mistakenly included. I was about to stop when suddenly it cut to the footage of Brandon on the local TV station. It ended up becoming of my favorite scenes in the film, thanks to the very enthusiastic TV show host and a young, guileless Brandon.

Another favorite part of making the film was simply working with Brandon and getting to know him throughout our many conversations together. He’s such an old soul was a joy to work with, which is of course not always the case when making a film about someone’s real life. He was always open and willing to go along for the ride, despite the vulnerability required.

I had several goals: I hoped some people might see a bit of themselves in the story and feel that they, too – despite having been made to feel othered in the past – belong in bluegrass and country music, that this music can be a home for everyone.

I also hoped that people would see Brandon’s story and say, “Wow, I didn’t realize there were still folks facing this type of persecution in the music industry.” This wasn’t so long ago. And unfortunately, as we all know, we are seeing today the continuation and resurgence of anti-LGBTQ laws and bigotry all over the country and the world. Another hope I have for the film is that by sharing stories that elevate the depth and humanness of the characters onscreen, folks from all sides of the political spectrum might, over time, begin to think about these issues in a new light.

What’s next? Recently the film screened to lovely and engaged audiences at the Sebastopol Documentary Film Festival and next it will play a bit farther from home at the Sound on Screen Film Festival in South Africa. I’m also hoping to show the film at music events or conferences, to continue to share Brandon’s story with audiences around the country.

What did you learn during the making of The Road Home that was unexpected? What will you take with you into future projects – whether in a similar vein or in another space entirely?

I learned so much! I learned the importance of finding that balance of pre-planning and knowing what the story is about while at the same time going with the flow of real-life, nonfiction storytelling – that is to say, you can’t actually predict how life is going to unfold, so you have to hold your preconceived ideas in one hand, while leaving room for the story to reveal itself to you as it unfolds in real time in the other. One thing I “learned” (in quotation marks because I’m still learning it…!) is to trust the creative process, with its highs and lows, self-doubts, rewarding moments, and ultimately, you find that you have gotten to the end of your creative process and survived! There are really too many things I’ve learned that I’ll be taking with me into future projects, so I’ll just leave it there for now.

Film, poster, and images courtesy of Bria Light.