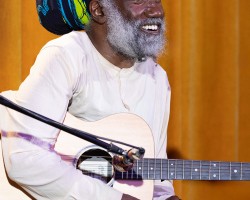

The music, sparse and spooky, sounds at the same time strangely universal and possibly from the last century, but as Jerron Paxton notes in his album title, Things Done Changed. The major difference on Paxton’s fifth album (including his 2021 duet set with Dennis Lichtman) is a big one. He wrote the songs.

“It wasn’t a very difficult decision,” Paxton said. “I had always had a list of tunes to record of my own compositions. I had to get enough cogent tunes to be an album, because you can’t have something that’s all over the place.

“You can’t have overtures with your hoedowns.”

The material on Things Done Changed is evidence that Paxton is no novice songwriter. These are words infused with hard living, what he calls “a good album full of blues tunes.”

In the standout track, “So Much Weed,” Paxton weaves amusement and a little resentment that there are Black people still serving time for minor drug offenses in an era when legal marijuana stores are in many states.

“Things done changed from the ’90s until now/ Lend me your ear and I’ll sure tell you how/ We got so much weed/ And the law don’t care/ My poor uncles used to have to run and hide/ Now they sit on their front porch with pride.”

A telephone call with Paxton is an adventure. He doesn’t back down and enjoys putting you on the spot if you’re susceptible to that.

A lot of your work is in vintage music styles. Why not a more contemporary sound?

Jerron Paxton: I play a diverse array of styles. I started off playing the banjo and the fiddle. As a matter of fact, I’m one of the few professional Black five-string banjo players in the world.

You have roots in Los Angeles and your family is from Louisiana. How did each of those places affect your music?

Well, I play the music of that culture, so it affected it in totality. It’s like being Irish and playing Irish music.

Could you give me a sense of how you evolved as a musician?

I started off with the fiddle and moved to the banjo and the guitar and piano and things like that. It was just a natural evolution, getting interested in one and that leading to another and to another, growing up in the house that was full of the blues. That’s mostly what my family listened to. [My aunt] almost listened to strictly the blues, while my grandma was kind of eclectic like me, and listened to everything. She liked Hank Williams and all sorts of country music and jazz and everything like that.

… I grew up in, first of all, a family full of Black people. So I got exposed to all sorts of Black folk music and Black popular music of every generation. You were just as liable to hear [Mississippi] John Hurt and Son House and Bukka White in my house as to hear Marvin Gaye, Michael Jackson, and Sam Cooke. If you heard bluegrass, that was mostly me. I was the one blasting Flatt & Scruggs and people like that.

You didn’t grow up in Louisiana, yet your music seems to be tied to music from the South.

My grandparents grew up there. My family migrated to Los Angeles with the death of Emmett Till and they brought their culture with them. But that doesn’t say much, because the majority of the culture in South Central [Los Angeles] is from Louisiana, so it’s not like we went someplace completely foreign. We went someplace where we were surrounded by people who were from where we were from.

I love the song “So Much Weed.” It’s a funny song about a serious thing, that there are many Black people in prison for marijuana convictions on charges that are now legal. Do people laugh when you play it?

I don’t play it live. Well, I don’t play it on stage. I usually play it in small gatherings for close friends.

Would you tell me more about your grandmother and how she influenced your music?

She was a fun, loving lady from northwestern Louisiana. My mother had to work, so I spent most of my time with [my grandmother] and grew up gardening and fishing, and getting the culture that you get when you’re raised in the house with your grandmother. Her mother was across the street. So I had four generations of family on one street.

So some of the songs on Things Done Changed were written some time ago. Why sit on them?

Some of the tunes were kind of personal and I just sort of kept them for myself and my friends. Other ones I had been singing on stage for a little while and said, “Maybe I should record this song first chance I get.” And other ones I had been singing since I was little, since my grandma helped find some words to them. So it’s all kinds of processes. Some of them take a lot of labor.

Do you mostly like to work alone live, or do you like to mix it up with other musicians sometimes?

It depends on the context. If I’m being hired as a soloist, that’s what you do, and that seems to be the most in demand. There’s not too many people who can go on the stage by themselves and hold the audience for 45 or 90 minutes or two hours with just the instrument. So people tend to hire me for that and there’s a lot of solo material unexplored because of that. But I play jazz music, so that’s a collective art. I play country music, which is also a collective art. I play blues music, which is a collective art. So you know, they’re all collective, but the solo is what people ask for. It travels easy.

So how would you like your career to develop? Do you have a plan?

I’d like to be filthy rich, just grotesquely rich and have a mansion with a lake. [Laughs] … But to be honest, I’m kind of enjoying building what I have, and I haven’t really seen any end to it. That might be a good thing. It just seems to be getting better. So I don’t see a need to worry about the end as much as how to make the best parts of what’s happening now last longer.

What kind of rooms are you working? Are you doing clubs for the most part?

I play festivals and basically any place that’ll have it, theaters and places like that. Any place that wants good music, I try to be there to supply.

Photo Credit: Janette Beckman