Following more than 30 years since first meeting and countless times sharing the stage during festivals, the two most accomplished fiddlers in International Bluegrass Music Association history have finally teamed up for their debut album together.

Released March 14 via Fiddle Man Records, the aptly titled Carter & Cleveland sees the combined 18-time IBMA Fiddle Players of the Year Jason Carter and Michael Cleveland flexing their bluegrass muscles on compositions from some of the most prolific songwriters around – like Darrell Scott, John Hartford, Tim O’Brien, and Del McCoury.

Coincidentally, it was with McCoury and his sons’ band, the Travelin’ McCourys, with whom Carter spent the last 33 years playing until the February announcement that he’d be stepping away from the groups to focus on his solo material and collaborative projects, like this one with Cleveland.

“I just thought it was time to start pursuing other things, like my own career,” explains Carter about his decision to leave the bands. “That being said, I never thought I’d be leaving the [Del McCoury] Band. I recently gave a fiddle lesson and the person I was teaching told me he was surprised I left the band and I remember telling him, ‘I’m kind of surprised too.’ [Laughs] But it’s so rewarding to be doing something new with my own band along with getting to play with Mike.

“I’m also really excited to see the McCourys play with their new mandolin player, Christian Ward,” he continues. “There’s no bigger fan of Del or the Travelin’ McCourys than me. This will be the first time since I was 18 years old that I’ll be able to sit out in the audience and watch his show. I can’t wait!”

It was also with McCoury where Cleveland, then 13, first met Carter back in the early ’90s during one of Carter’s (then 19) first gigs with him.

“[The Del McCoury Band] has always had the players that I aspire to be like,” says Cleveland. “I remember going to and recording the band’s shows from the soundboard when Jason was just starting out with them. Then I’d go home and try to play guitar over the recordings to best imitate each part. They quickly became some of my biggest influences in this music, and still are.”

Ahead of the album’s release, BGS spoke with Carter & Cleveland over the phone to discuss the duo’s years-long partnership, the process of bringing this record to life, and their thoughts on the history of duo records in bluegrass music.

You have tunes from Del McCoury, Darrell Scott, John Hartford, Bill Monroe, Buck Owens and other roots music legends on this project, but no originals. What was behind that decision?

Jason Carter: Well, for me, I didn’t have any original tunes at the time we started doing this, so I just started throwing out songs I liked. Then I called some songwriters – Tim O’Brien, Terry Herd, Darrell Scott, and others – and the songs I liked most of what they sent I then played for Mike. I’ve only written one fiddle tune so far, but actually have four or five writing sessions lined up this week, so maybe if there’s a Carter & Cleveland Volume II, I could have a cut on there.

Michael Cleveland: We’ve talked about needing to sit down and write together, it just hasn’t come to fruition yet. When I’ve sat in with Del or Jason in the past we never had time to rehearse, which is similar to how these songs came together. We were able to talk about material and send things back and forth, but we didn’t have much time to sit down and rehearse before recording because we’re both so busy. I hope we get to do that someday, but at the same time songwriting isn’t the main focus for me. I know folks that’ll write a tune every day, but for me that only happens once in a while; when it does I make sure to run with it.

What are some standout songs for y’all on this project?

JC: That’s tough, because I like all the songs on the record. At any given time I could have a different favorite. There’s also some that didn’t make the record we still have in the can and might put out later that could actually be my favorite songs. That being said, I really like the part of “With a Vamp in the Middle” where [Mike] finger picks the fiddle while I’m strumming…

MC: That was your idea!

JC: I heard you play something that sparked that. [Laughs] When you’re in the room as a fiddle player and you hear Michael Cleveland play, it’s all special. He [is] leagues above everyone else.

MC: It’s hardly ever a problem that you have too many good songs, but that was definitely the case when we went in to record. As soon as we put the word out about it we had a bunch of our musical heroes sending us songs to record and they were all great! When I first heard the demo of “Give It Away” from Tim O’Brien I liked the song immediately. Tim was playing old-time banjo on it in the key of D while singing, but once I heard Jason sing it in the key of B I knew it was meant to be a hard-driving bluegrass song.

I also really enjoy “Kern County Breakdown.” The only time I’d ever heard that – which made me want to record it – was from Alison Krauss. She used to play it as a fiddle instrumental and I always wish she recorded it. I don’t know if it’ll happen, but I’m still holding out hope that she’ll put out a fiddle album one day.

She does have her first album in 10 years dropping later this month, so you never know!

Throughout the history of bluegrass music there have been many timeless duo records from the likes of Ralph Stanley & Jimmy Martin to Ricky Skaggs & Tony Rice to Bill Monroe & Doc Watson. What are your thoughts on being the next chapter in that series of collaborations?

JC: I hadn’t really thought of it like that before…

MC: If this album is mentioned in the same breath as any of those, that would be great! We also talk a lot about our favorite twin fiddle albums, which this seems to be more of, and have tossed around the idea of doing this project for 15 years. There’s albums from Kenny Baker and Bobby Hicks, Buddy Spicher and Benny Martin, Buddy and Vassar Clements, and so many more, but there hasn’t been one for a long time now. That’s what originally inspired us to do this. In the last few years people have also finally figured out what a great singer Jason is, which afforded us a lot more room to experiment than if it were a twin fiddle instrumental album.

JC: Mike just has such a good ear. I remember sending him a couple versions of demos I played and sang on and he’d immediately get back to me with suggestions like adding a fiddle lick at the beginning, like on “Outrun The Rain.” He thought it would be great for a high harmony thing two above the lead. As soon as he heard this stuff he had ideas. It was really cool to see how that all came together.

Mike just mentioned the idea for this album has been floating around for 15 years. When did y’all eventually get to work on it?

JC: We started recording a couple years ago. The first session we recorded we actually did at [guitarist] Cody Kilby’s house during COVID, then it was another year or so after that until we got working on it again. Because we didn’t have any rehearsal time, I remember sending voice memos of myself playing fiddle, guitar, and/or singing to Mike to listen to and send suggestions back. I remember being at a show with Del tucked away in the dressing room by myself trying to record versions of these songs or trying to run through an arrangement before sending it to Mike through text message.

MC: I had a great run with the label I was previously involved with, Compass Records, but they weren’t really interested in collaboration albums. With all of my projects and Jason as busy as he is, we were always just in the middle of other things until Jason put out [2022’s Lowdown Hoedown] and I completed [2023’s Lovin’ Of The Game]. It was around that time we decided to take the leap and finally start working on this.

Speaking of taking a leap, I know y’all co-produced this record too. What was your motivation behind that?

MC: We had talked about bringing somebody in. I’ve worked with Jeff White for years on my albums. In a way he helped to produce this one too, which is fitting because I always felt like we co-produced my albums together. For this record there were people we’d send stuff to listen to, even down to the final mixes, just because we respect their opinions, but the final calls were all us.

JC: Even when you’ve got someone like Bryan Sutton in the studio for tracking, he may have an idea he throws out that becomes a big help as well. That could come from anyone involved in the session, even engineer Sean Sullivan, who we leaned on heavily as well because they do this every day. These people are here for a good reason, because they’re super talented and play some of our favorite music. And when it comes to Cleve, I’m all ears. He always has good advice.

MC: When you first start recording, you don’t always know what sounds good. It’s like with playing, singing, or anything else, the more you put yourself in those situations the more you understand what you want to hear and how to achieve it. Working with Jeff in the past, we’d be together during the day when all of the sudden he’d say, “Hey Mike, I gotta take off for a few hours, produce for a while.” It freaked me out the first time he did that, but it forced me to get comfortable in the situation and forced me to trust my ear more. Jeff having that faith in me also gave me a little more confidence in myself that I was making the correct decisions and to continue trusting my instincts.

JC: With the Travelin’ McCourys, all of those records were produced by the band along with most of the stuff we did with Del, too. I did produce my solo record, Lowdown Hoedown, though. But even on that, when we were recording Sam [Bush] and Jerry Douglas were there. I remember Jerry – who produced a lot of the McCourys’ stuff early on – always had great ideas on arrangements and different things to put in when he spoke up, which was a huge help. Getting to be in the studio with him is an education you can’t get anywhere else.

Jason, you briefly spoke of a few of the album’s players there. But they’re far from the only top-notch pickers you have on this record, with the likes of Vince Gill, Charlie Worsham, and Sierra Hull, among others. How’d y’all go about deciding who to bring into the fold?

JC: We just tried to think of who would best fit with the songs as we listened to demos for each.

MC: It also came down to who was available at certain times. Guys like Bryan Sutton, Cory Walker, and Alan Bartram played on most of it. I remember days where Sam Bush was available on mandolin and others where Harry Clark filled in. Some of the first sessions we did after the pandemic were with Cody Kilby and Casey Campbell followed by David Grier and Dominick [Leslie].

And going back to something Jason said earlier, I also leaned on Bryan a lot, specifically about what songs he thought it would be good to have Sam on, which led to his inclusion on “Middle of Middle Tennessee” and a few others.

What has music, specifically the process of bringing this record to life, taught you about yourselves?

MC: This was one of the first things I’ve done without a producer being there. Most of the time we would agree on decisions, but other times you don’t know what the right thing is and somebody has to make the call, because that’s typically something a producer would do. When it’s just you there’s no question, but when you’re working with somebody you want to make sure it’s a collaboration and not one person running the ship. Recording this album has taught me to be more aware of that.

JC: The singing part of this too, that’s still pretty new to me. I’ve sung on other people’s records, my solo album and with the Travelin’ McCourys, but being the lead singer throughout is a new venture for me and something I really enjoyed getting to do with Michael.

What do the two of you appreciate most about one another as both musicians and people?

JC: Everything about Mike’s playing, he’s just on another planet right now, and as a person he’s the same way. I recently got married and Mike was my best man, because no matter what he does he is the best man!

MC: Hearing Jason play with Del, he’s always been the fiddler I’ve wanted to be. We’re both into the same stuff, which is why I think we work together so well. It’s why we’re able to jump on stage and play twin fiddles without rehearsing, which is usually a mess when you do that. Getting to work with him on this album has been a dream come true for me.

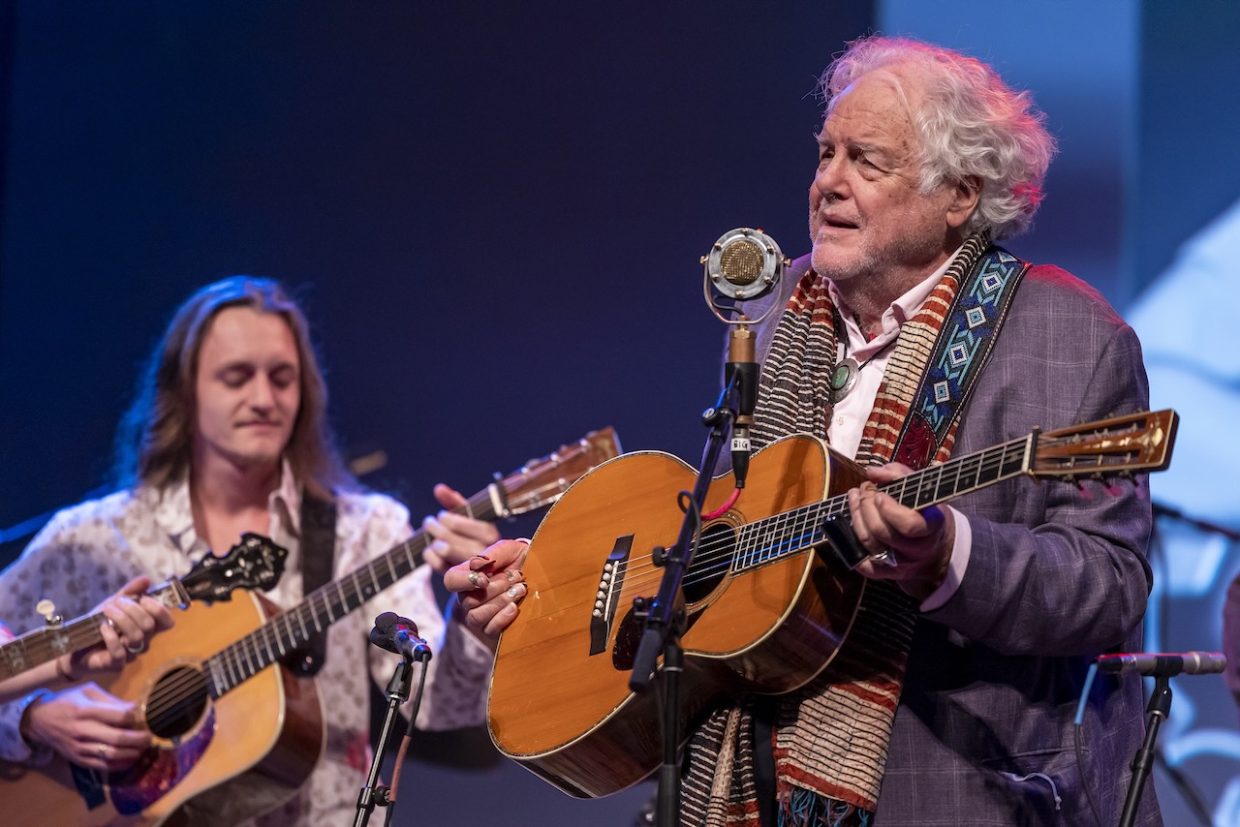

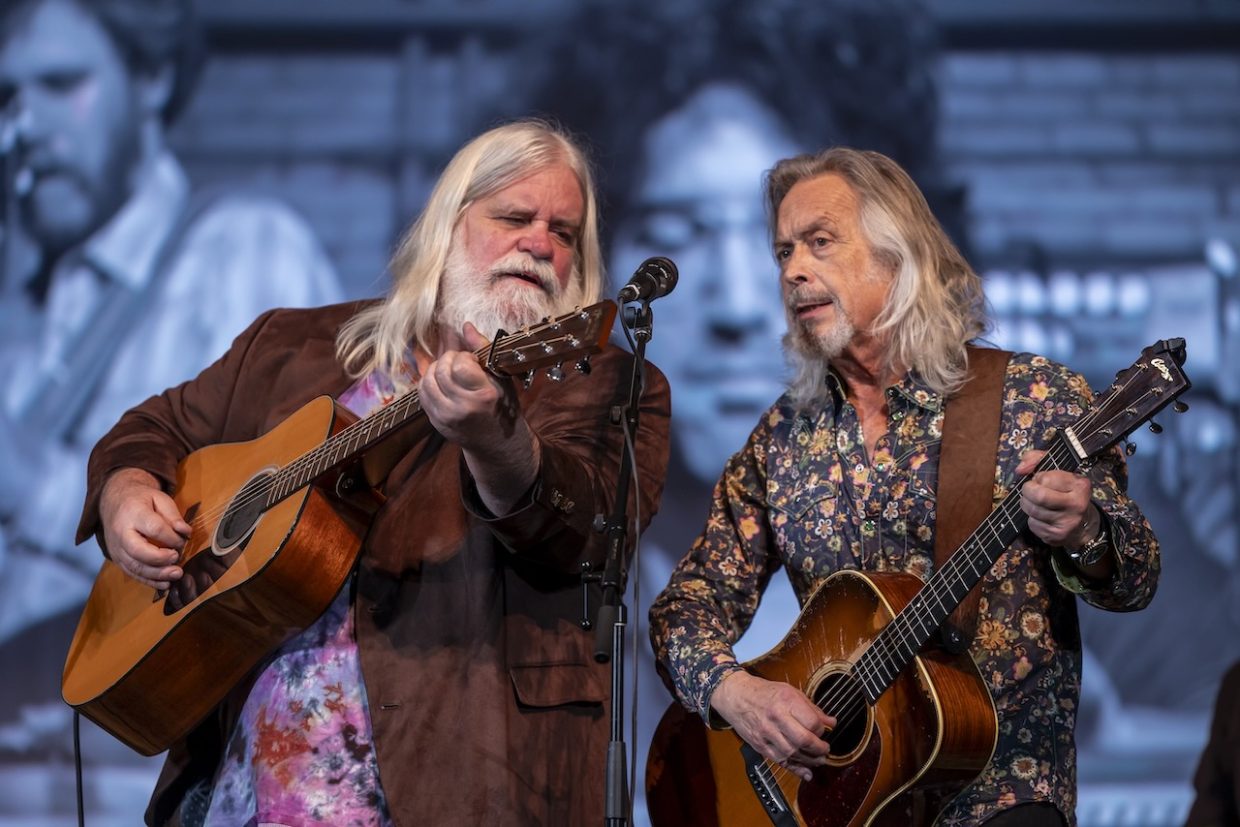

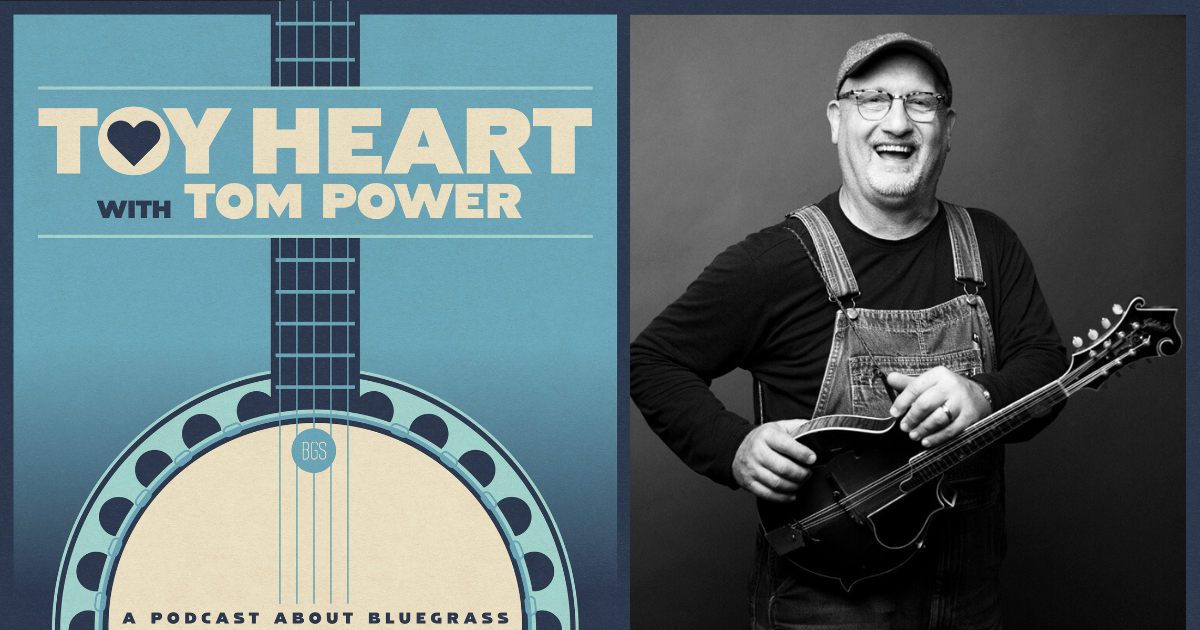

Photo Credit: Lead image by Sam Wiseman. Square image by Emma McCoury.