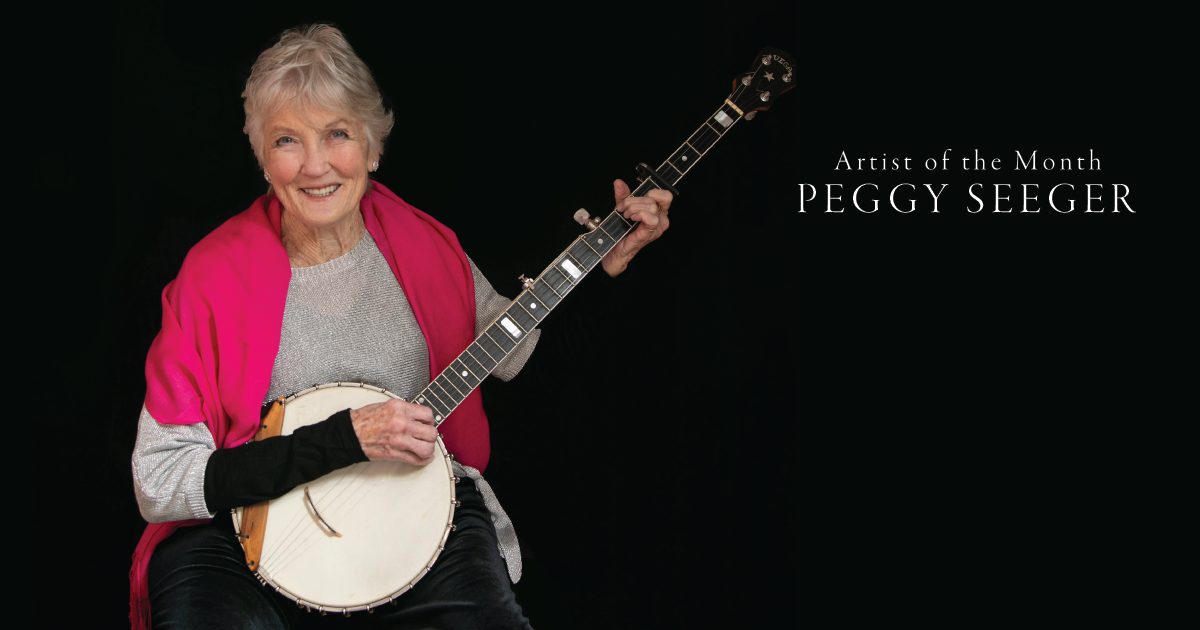

Peggy Seeger began her life surrounded by brilliant and groundbreaking musicians: a mother who was an internationally known composer; an ethnomusicologist father; half-brother Pete, legendary for both his songs and his political courage; brother Mike, musician and song-catcher. In the latter years of her career, she is making music with what she calls her “created” family — her three children who share her delight in songwriting and performing.

Like Pete, Peggy was an outspoken leftist who was blacklisted in the 1950s, and she has never stopped speaking her mind through lectures, interviews, and her music. On the occasion of her newest release, First Farewell, we were honored to speak with her from her present home near Oxford, England. Here is the first of our two-part interview with BGS Artist of the Month, Peggy Seeger. You can read part two here.

BGS: Listening to your new recording, I was struck by how beautiful your voice is. Do you have to work at keeping it that way?

Seeger: I don’t feel it’s beautiful. It’s so reduced from what it used to be. What’s happened is I’ve moved down into the lower ranges where it’s more vibrant. And there I can, for some reason, feel more emotionally connected. I practice every day. I actually sit down and sing as if I’m giving a concert every day. It’s like any muscle: if you keep it to keep it working, you won’t lose it. And I walk every day. And I walk quite fast, so sometimes I get out of breath. You need to build your lung capacity. I’m pleased that you think it’s beautiful. I never thought it was.

What prompted you to create this new album?

My children have realized that there’s nothing else that I enjoy as much as singing. I don’t have any other way of expressing myself. I don’t cook well. I do make sourdough bread. … Five years ago, they asked me what I wanted for my 80th birthday, and I said I want to tour with my two sons. They said they would do a week of touring – and it worked out to be 16 days. But they said we needed an album to tour with. So that was when we recorded my previous album called Everything Changes, and I realized how strong it is, working with an entire family network.

Everyone in my created family one generation down is involved: my two sons, my daughter and two daughters-in-law perform all that I need: a manager, a minder, accompaniment, co-writing, graphics. It’s all there, including doing the recording. If you’re a singer for a living you need to put out a new recording periodically. And so that’s what we did [with this new project]. We took a couple of songs that were quite old. “The Tree of Love” I made up about 10 years ago; “How I Long for Peace” I made up 20 years ago and never recorded. “Gotta Get Home by Midnight,” that was created strictly to be an encore. Now, that’s about the most egotistical reason! We had about 20 songs, and we just chose what was best for this album.

Can you talk about the song “The Invisible Woman”?

That was written with my son Neill. When he came to work with me on a song, we just looked at each other and said, “What should we write about?” And neither of us jumped at anything. So, then we started talking about our joint lives. He’s 61. And he said, “You know, Mum, I’m beginning to feel invisible.” It worked out that young women weren’t interested in him anymore. You know, in actual fact, they are. It’s just that he doesn’t necessarily sense it. So, I said, “Try being an 85-year-old woman, if you want to be invisible.” Because, you know, as older women, the baby factory is shut. We’re redundant as far as productive units are concerned. So, what have we got to offer? We’re not looked on as wise. We’re shunted off, and we have been ever since we’ve been living under a patriarchal system.

Do you visualize any specific incidents from your life when you think about that song?

Well, of course, I am both visible and invisible. I’m visible in in my career, although folk music is a fringe music. It’s not way up there like classical music, and it’s not so broad or in-your-face as pop music. So, I am visible in that field. But the minute I walk out in the city, or when I’m just a member of the public, I’m invisible. Occasionally a nice man will ask if I want help crossing the street. I became aware of this once when I was walking with my daughter. She was absolutely dressed to the nines. She would have been 20 or 25, so I would have been in my 60s. And we kept passing men who would do this: They’d look at me and they’d see my hair and then they’d look immediately to her and go like that [rolls her head up and down and up]. Their eyes were on her. They were not on me. Yeah, I’m very grateful for that. I’m tired of being under male scrutiny. From age 15 to about the age of 45, I put up with the groping and being pushed up against a wall. And I’ve had it! They don’t do that anymore. I’m an old woman and I don’t mind at all.

I imagined folk music as being, in a way, above gender discrimination.

Folk music is no way free of gender discrimination. It is packed with it. Full of it, hugely full of it. In the music, women are dismissed. We are victims. In some of the folk songs we were sent off for nagging our husbands. We were battered and beaten in some of the songs. Women were left with children in their arms. We were endless victims. I have a three-hour lecture on the position of women in folk songs. And it is despairing. And some of it is so outright misogynistic.

There was a song Pete used to sing, and he thought it was funny. At one point, before I became a feminist, I thought it was funny.

Oh, I had a wife and got no good of her,

Here is how I easy got rid of her,

Took her out and chopped the head off her

Early in the morning.

Seeing as how there was no evidence

For the sheriff or his reverence

They had to call it an act of Providence

Early in the morning.

So, if you have a wife and get no good of her

Here is how you easy get rid of her

Take her out and chop the head off her

Early in the morning.

It was so vicious that it was funny. You couldn’t believe that anybody would sing about this. So, if we really look at a lot of the content of the songs, women are just handed from man to man and were killed by a lot of the men. And a lot of the folk songs actually document real murders, like “Ellen Smith” and “Omie Wise” and “Pretty Polly,” and the other ones like Laura Foster in “Tom Dooley.” Endless murders — especially after we get pregnant. I still love the songs unfortunately. To me, they’re historic pieces. And they talk about what we’re battling now.

Your album sounds like you’re acknowledging loss, and at the same time, acknowledging contentment. Is that a fair characterization?

Well, people in my family who lived to the age of 85 generally live into our 90s. So, I’m looking at maybe another, hopefully, 10 or 15 years of life. And the recognition and acceptance of that makes a whole new frame of life. You live differently with that. I have mental snapshots of my past. I have oceans of them. So, the pictures in my head and what I’ve learned and experienced just flow back and forth with the tides.

That’s where songs like “Dandelion and Clover” come from. I didn’t set out to make a song about memory with “Dandelion and Clover.” All of a sudden, the thought of a little boy coming to our kitchen door just flew into my head. He died when he was 8. He had a seizure on the schoolroom floor. He and I used to sit out in the field — there was a four-leaf clover field. We’d sit out there and talk about marriage and having babies when we were 8. And then the tragedy of him dying … but I didn’t feel it was a tragedy because I knew he was going to come back and marry me because I was told that’s what he would do.

In writing we try to marry up opposites or marry up correlated subjects, as in the song “Lubrication.” Or marry up diverging thoughts as in “How I Long for Peace,” contrasting peace with acts of violence and profit and greed. And to put those into a quiet, peaceful song.

What has it meant for you to be, as you say, in lockdown?

Nothing, because I’m a hermit anyway. I miss going into town, I miss going to the hairdresser. I miss going shopping, because other people shop for me, although now I’ve had two vaccine shots. So, I think I’m going to start shopping for myself again. But I’ve always been a hermit, I’m happy with my own company. My partner lives in New Zealand and I haven’t seen her for two years, because of COVID. And we’re not compatible for living together. So, I live on my own. I take care of myself. I keep busy. My god, I keep busy. There’s so much to do. And I talk to nice people like you.

(Editor’s Note: Read part two of our Artist of the Month interview here.)

Photo credit: Vicki Sharp