In our last Bluegrass Memoir, “Beginnings,” I described David Hoffman’s documentary, Earl Scruggs with his Family and Friends. By the time NET aired it, the Revue was already off and rolling with Earl’s new music.

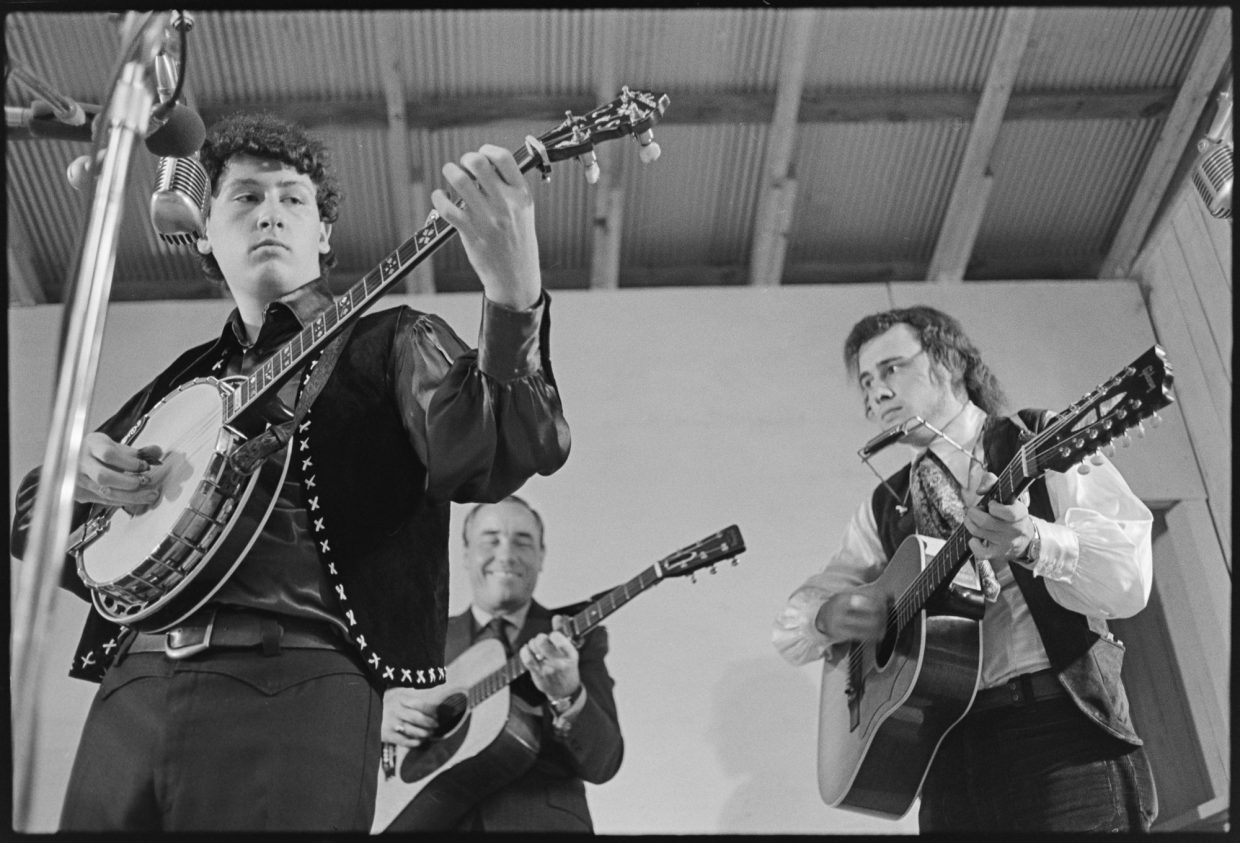

In 1970, bluegrass festivals – the first was in 1965 – were becoming quite popular. The music’s supporters had discovered that such events could present their favorite music to broader, younger, urban audiences. These larger crowds brought their tastes and preferences with them. At these booming festivals, new acts like the Earl Scruggs Revue spoke to musical perspectives shaped by contemporary popular music.

The Revue played to large numbers at Monroe’s Bean Blossom Festival that spring and to Carlton Haney’s Camp Springs Festival on Labor Day weekend. Earl’s solo album, Nashville’s Rock, and Randy and Gary’s solo album, All the Way Home, were released that year.

In 1971, Columbia released Earl Scruggs: His Family and Friends (C 30584), a soundtrack album that included much of the content of Hoffman’s documentary along with two additional fine vocals by Doc Watson. In its liner notes, Don DeVito characterized the show’s topic:

Earl Scruggs is a man who has paid his dues. You can forget the generation gap … Earl has always been an innovator and an adventurer…

Also in 1971, newgrass music emerged. Its key figure at that time was singer-songwriter and banjoist John Hartford, whose “Gentle on My Mind” had been a 1967 Glen Campbell hit. John had flourished in the LA television business as a writer for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and a performer on The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour.

Hartford and Scruggs – they’d met in 1953 – had developed what Bob Carlin, in My Memories of John Hartford (University Press of Mississippi) calls “a deep friendship.” When Hartford returned to Nashville in 1971, he recorded what is now considered the first newgrass album, Aereo-Plain. The Revue’s Randy Scruggs played bass on this ground-breaking disc alongside Tut Taylor, Vassar Clements, and Norman Blake.

The Revue and Hartford were at the center of Nashville’s jam-based music, which embraced musicians from new scenes blending rock and older genres – folk, bluegrass, and country. Both bands appeared at a number of bluegrass festivals in 1971 and the Revue was busy recording in Nashville.

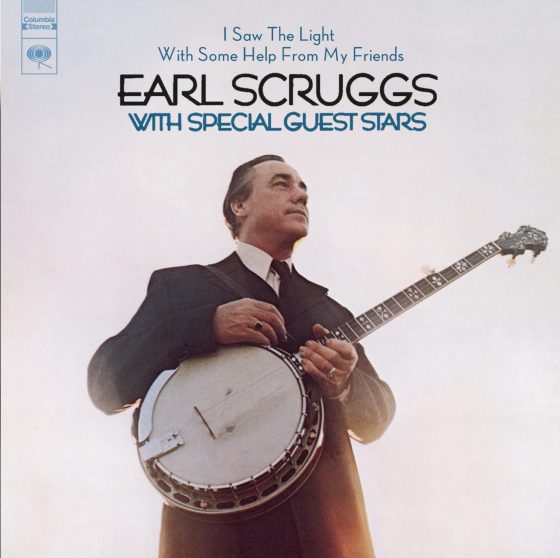

I Saw The Light With Some Help From My Friends (1972)

Earl was working on his next album, I Saw The Light With Some Help From My Friends: Earl Scruggs with Special Guest Stars. The back liners of the album (Columbia KC31354) described it as “Earl Scruggs and The Earl Scruggs Revue in performances with Linda Ronstadt/The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band/Stacey Belson and Arloff Boguslavaki.”

Stacey Belson was a pseudonym for blues singer Tracy Nelson, then with the band Mother Earth. Arloff Boguslavaki was Bob Dylan’s pseudonym.

Bill Williams’ liner notes describe the fabulous jam sessions that were happening at the Scruggs family house – hence the album’s concept:

Picture, if you will, the group sitting around together at the Scruggs home (although the actual locale was shifted to Columbia Studios) …

For this album, the studio became the living room and the producer was Don Law, the Nashville vet who’d worked in the ’30s with blues legend Robert Johnson and western swing pioneer Bob Wills and in the ’50s with Flatt & Scruggs.

At this Scruggs family jam session were Earl and sons along with their Madison High School contemporary, drummer Jody Maphis. Also in the room were fiddler Vassar Clements, in the process of moving from Hartford’s band to join the Revue, and several others who’d later join the Revue, including pianist Bob Wilson, a Detroit R&B musician who’d moved to Nashville and subsequently recorded with Bob Dylan.

Each of the featured star guests are heard in solo, sometimes singing in harmony with each other. Earl plays on every cut. Great to hear his backup work with all its nuances! Randy’s lead guitar and Vassar’s fiddling appear throughout.

It was as if these people had showed up at the Scruggs home one evening to play for and with each other – an old-fashioned domestic music session, with the host going around the room inviting each to perform and providing musical backups for all. The evening’s repertoire was the kind of stuff you might expect at such an event: mostly recent country, folk, blues and rock – things you might have heard on the radio lately in 1971.

The sound was that of contemporary popular music, suggesting that this was what you’d hear if the Earl Scruggs Revue came to your living room, festival, or auditorium.

The album’s first side opens with an LA country soul rock tune, Bonnie and Delaney’s “Lonesome and a Long Way From Home.” Gary is singing lead and playing bass; Nelson adds harmony. This is rocking R&B – Wilson’s piano opens the break and, with fiddle and drums, keeps it rocking to the end. Earl’s banjo is out front throughout.

Next comes Merle Haggard’s “Silver Wings,” sung by Linda Ronstadt with harmony by Nelson. The backup piano and Dobro are joined by a fiddle break. Straight-ahead Nashville country.

Track three features “Boguslavaki” (Dylan) singing Charles E. Baer’s 1896 hit, “It’s a Picture From Life’s Other Side,” a song that had gone into the folk tradition and been frequently recorded by hillbilly and gospel singers in the ’20s and ’30s. The laid-back fiddle, bass, and drums, along with Nelson’s harmony on the chorus, mark this as a parlor folksong.

It’s followed by Nelson’s performance of “Motherless Child Blues,” where accompanying musicians Earl, Norman Blake, Randy, and Vassar stretch out with some nice blues breaks.

This side closes with Mike Nesmith’s “Some of Shelley’s Blues,” performed with members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, with Gary Scruggs and Jeff Hanna doing the singing and Earl and Randy both taking instrumental breaks.

The second side of the album opens with a vocal by Gary on another Bonnie and Delaney cover, “Never Ending Song of Love.” Ronstadt sings a county cover, Cash’s “Ring of Fire.”

Dylan brings out another pre-war country folk oldie, a great “Banks of the Ohio.” While Nelson is featured singing folksinger Bruce “Utah” Phillips’ “Rock Salt and Nails,” a song first recorded by Flatt & Scruggs in 1965, with Ronstadt adding harmony on the chorus.

The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band contributes another Nesmith song, “Propinquity.” The side closes with the album’s title track, a sing-along for everyone, “I Saw the Light.” The album was released in 1972.

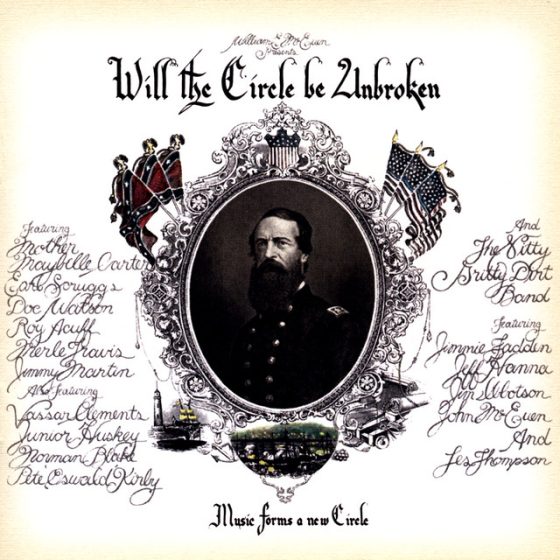

Will the Circle Be Unbroken (1972)

Around the same time as I Saw The Light was made, banjoist John McEuen of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band asked Earl to be on their new three-LP concept album, Will The Circle Be Unbroken. Scruggs was playing in Denver with the Revue when he and McEuen met. The Dirt Band’s sound, with McEuen’s skilled Scruggs-style banjo, appealed to him, as did their project to honor and make music with the earlier generation’s pioneers. That had been his own goal in bringing Maybelle Carter into the studio to record with Flatt & Scruggs back in 1961.

Earl, well-connected in Nashville as an Opry star with record, television, and movie hits, helped bring a number of his country music friends into the project. Both Gary and Randy were also involved, as were several of Hartford’s Aereo-Plain band members, notably fiddler Vassar Clements and Dobro player Norman Blake.

Unlike Earl’s Nashville’s Rock album, which covered recent rock and pop hits on the banjo with Nashville studio backing including electric instruments and, on several cuts, a soulful female vocal trio and a string section, this album had completely acoustic backup by the Dirt Band as they covered legacy hits by country, bluegrass and folk pioneers like Roy Acuff, Maybelle Carter, Doc Watson, and Jimmy Martin.

Earl played a pivotal role in the making of these recordings, playing guitar or banjo on sixteen tracks. The whole Scruggs family can be heard: Randy contributed guitar, autoharp, or voice on eleven tracks, Gary sang on eight, and Louise and Steve sang on one track.

Of the many interesting performances on this award-winning album, Randy Scruggs’ acoustic guitar version of “Both Sides Now” was perhaps the most remarkable; the final selection in the set, it followed a group sing-along of the title track, similar to the closing on the Earl’s I Saw The Light, in which all of the Scruggses sang. These recordings, released in 1972, were made in August 1971.

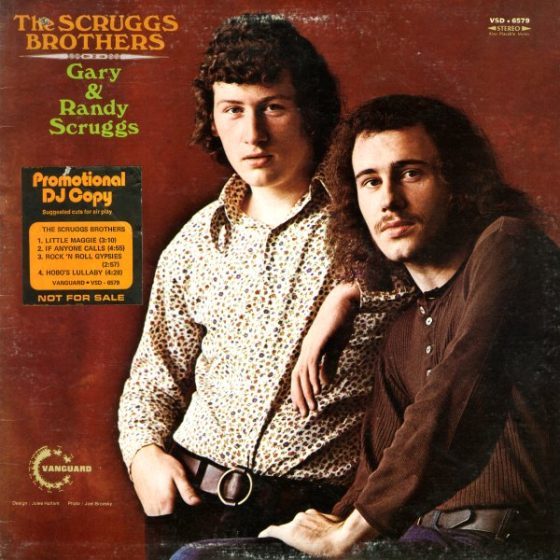

The Scruggs Brothers (1972)

Also recorded in 1971 was Gary and Randy’s second Vanguard album, The Scruggs Brothers (Vanguard VSD 6579). Some of the same musicians who played on I Saw The Light performed here, like Tracy Nelson, the Dirt Band’s Jeff Hanna and John McEuen, pianist Bob Wilson, and drummer Karl Himmel; but the album had more of a country rock sound. It opened with “Little Maggie,” a song Flatt & Scruggs had recorded at Carnegie Hall in 1962. With Gary’s bass and Jody Maphis’ drums leading the way, it sounded something like the Nashville studio A-listers Area Code 615’s 1969 version.

Throughout the album, Randy played a majority of the solo breaks, some on acoustic guitar but most on electric, in a heavy metal style similar to what I heard him playing in Maine in 1975. Four tracks were their own compositions, two by Gary and two collaborations.

On one, the instrumental “Trousdale Ferry Rag,” Earl played banjo. This up-tempo, bluegrass-style piece has an unusual ending, shifting to a slow blues beat. Most notable is Gary’s “Lowlands,” a great ballad set to the tune of Earl’s “Sally Ann,” which both brothers had been hearing at home all of their lives (Flatt & Scruggs recorded it in 1960). Gary plays guitar, Randy picks banjo.

Covers of older (dare we say traditional?) material includes a rocking version of Jimmie Rodgers’ “T for Texas,” and the other cut on which Earl played banjo, “Hobo’s Lullaby,” which features a sing-along chorus similar to that on the closing of the I Saw The Light and Will The Circle Be Unbroken albums. Another older piece was “The Johnson Boys” (Flatt & Scruggs did it 1962) on which John McEuen’s frailed banjo created the album’s most old-timey sound.

The boys’ continuing involvement with country rock is reflected in two songs that originated in 1967 with the LA band Hearts and Flowers. “Rock and Roll Gypsies,” which closes the first side of the album, seems to have been an attempt to garner radio play – it’s the only track on the record to include string section backup. The other Hearts and Flowers-connected track, “Bugler,” a sad song about the death of a dog, had recently been covered by Clarence White with the Byrds.

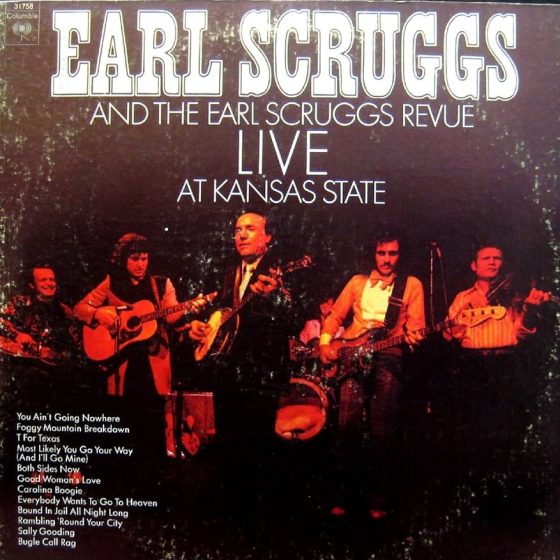

Live at Kansas State (1972)

During this year of extensive studio recording, the Revue was also out playing on the road. Although Earl Scruggs: His Family and Friends included a few examples of the group in action outside the studio, Live at Kansas State (Columbia KC 31758) was their first full show album.

Many of the songs the Revue did at this 1972 concert remained in the band’s regular repertoire and showed up, for example, at the 1975 Maine concert, including “T for Texas,” “Paul and Silas” (they titled it “Bound in Jail All Night Long”), “Sally Goodin[g],” “Carolina Boogie,” “Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven,” and “Foggy Mountain Breakdown.”

Several were on their recent albums, like “You Ain’t Going Nowhere” and “Both Sides Now.” Bluegrass classics included “Good Woman’s Love” and “Bugle Call Rag.”

In 1998, a reviewer for No Depression wrote that Live at Kansas State was “probably their album most deserving of a full reissue … a surprisingly cohesive ‘bluegrass-rock’ blend, the likes of which has seldom been heard since.”

In 1972, the band included fiddler Vassar Clements and Dobroist Josh Graves, a bluegrass icon who’d just left Lester Flatt’s band. The album package has several photos of the band; these are notable in that they include everyone but pianist Bob Wilson, who is very much present in the album’s audio.

Wilson had moved to Nashville from Detroit’s R&B scene. His first years in Nashville were slow going, but that changed when Bob Dylan came to town to record Nashville Skyline and wanted “a funkier piano sound than the usual Nashville cat could produce.” The success of his work on Dylan’s album gave him plenty of studio work and he also found time to go on the road with Scruggs.

“When I was with the Earl Scruggs Revue,” he recalled, “Earl always introduced the band, and when he came to me, he always told the crowd, ‘And this is the man who played piano on Nashville Skyline, Bob Wilson.’ I must admit the applause felt really good.”

In his memoir, Bluegrass Bluesman, Graves spoke of the challenges he enjoyed while rocking with the Revue: “Earl and that bunch forced you to work up new licks. You had to come in there on the stuff they were playing. It was so loud I couldn’t hardly stand it, but I really enjoyed it. It opened a lot of doors for me. They were into a lot of things. …”

“Earl was doing the same old tunes with a little modern touch. Earl got bored with bluegrass – I’ll tell you that. He just didn’t want to play it anymore. They had that big beat, that sound behind it, and that’s what he liked.”

“He’d play ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’ with that band and people would go wild.”

I saw this, too, in Orono in 1975.

The Revue carried on into the early ‘80s, with albums that drew from contemporary pop music and brought younger country, folk, and rock stars in as guest artists. We’ll touch on a few of these next time.

(Editor’s Note: Read our prior Bluegrass Memoir on the Earl Scruggs Revue here.)

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg.

Inset black and white photos by Carl Fleischhauer, courtesy of Carl Fleischhauer.

Edited by Justin Hiltner.