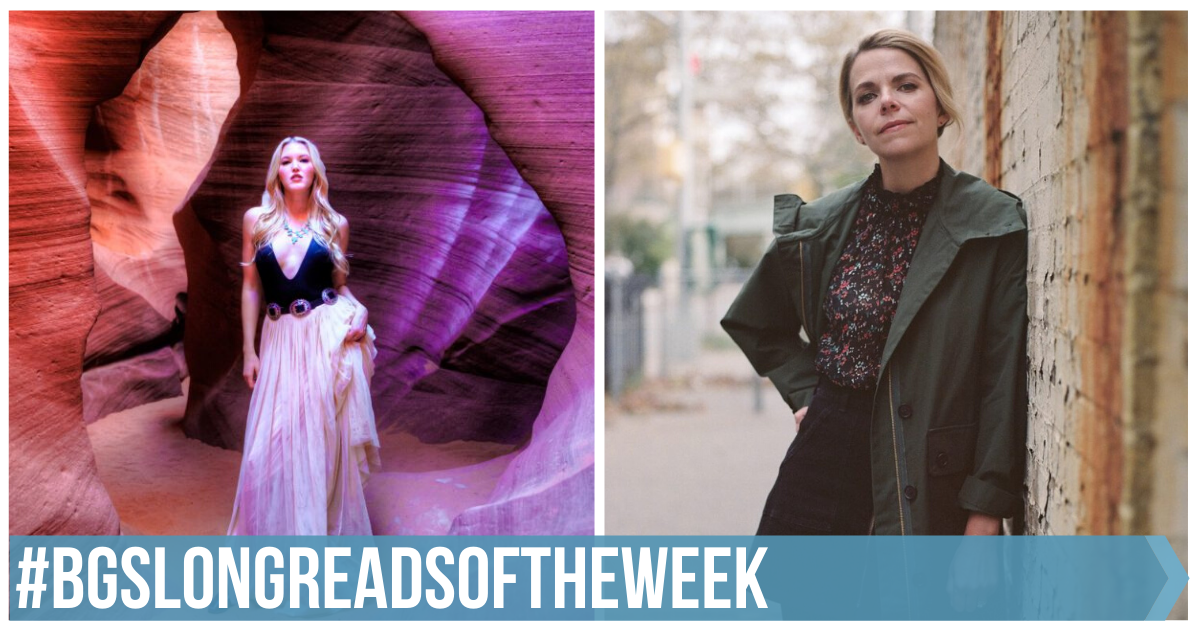

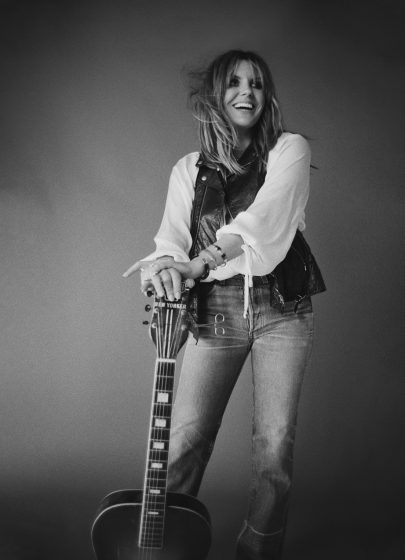

As she releases an emotional and illuminating new album, Old Flowers, Courtney Marie Andrews finds herself facing the exact scenario in which she began the creative process: solitude.

Over the course of months writing the material that would become the 10-song LP, the only alone time she enjoyed was while crafting songs, tinkering with melodies, or teasing out narratives from her own subconscious, interrogating herself as a writer, as a narrator, and as a human. But instead of personally carrying her crop of new material out into the world, she’s tasked (like so many of us right now) with sharing these tender buds while she remains in place.

Listening to Old Flowers in this light is like receiving an artful and tenderly dried bouquet. Even as she reflects on the life-changing experiences of the last few years, this album feels made for this moment, bolstered by the sharp, intelligent compassion evidenced on every track and in every lyric. For our Cover Story, we connected with Andrews by phone and began our conversation, as we all do these days, commiserating over shared though separate isolation.

Courtney Marie Andrews: It’s funny, when I was writing this record I felt like I was in my own personal “quarantine.” It was my first time being alone in over nine years, it was my first time living alone, I moved to Nashville, I was making new friends. I felt, in my own way, that I had found this island. There’s definitely an in-place feeling to the record more than my other records.

It’s really insightful that you said my songs are like mantras, because sometimes, as the narrator [of these songs], I am sort of giving myself therapy. Especially on this record. It does feel like a mantra, particularly on songs like “Carnival Dream,” where I just say over and over again: “Will I ever let love in again? / I may never let love in again.” It’s sort of me accepting that that may be the case.

Another line that may stem from the same idea: “I’m sending you my love and nothing more.” It’s as if you’re reminding yourself of that boundary, rather than the person you’re singing to. Do you agree? That’s the light bulb that went off in my head.

I’ve never thought about it that way, but yeah, it is a boundary. It’s absolutely a boundary. It’s the closing line for the record for a reason. It’s the closing chapter of this saga.

When I first wrote them, it was like these epiphany moments. More than May Your Kindness Remain I see this record as songs born out of necessity, to get these feelings out. I felt grumpy! The first year was just getting them out, overcoming that first obstacle — especially when you’re in a relationship with someone that long. There’s so much to process you can’t even see what’s in front of you. Now, when I’m listening to the songs in isolation I’m learning more about me as a narrator. More about, “Where do I stand in all of this?” and “Where do I stand now?”

Last year, the only time I allowed myself to be alone was when I was writing songs. Otherwise I was mostly just trying to distract myself constantly with work, or music, or friends, or drinking. You know, everything you do to distract yourself. This learning about the narrator in these songs — that narrator being myself — has been my current isolation process.

Normally what we’d be talking about right now is how these songs change as they bounce off of audiences, as you’re feeling people besides yourself take ownership of them. Obviously that is still happening, it’s an inherent part of how humans consume music, but the way we relate to that phenomenon is so different now. It’s happening through live streams, through screens, across so much distance. What’s tangible to you about that difference?

As any human probably feels right now, I feel this is very nuanced, has many sides, and I have many days where I feel one way and many days where I feel another. Especially in regards to quarantine and being so uncertain of everything that’s to come. I will say, if I’m being 100 percent frank, so much of knowing people’s true feelings about my songs and how they’re connected to them, for me, is in performing. And talking to someone at the merch table or in the audience. It just feels so much more real. It feels like an AI [artificial intelligence] right now! [Laughs] I know that people are connecting to it, I’ve gotten so many lovely messages about the songs, but it just doesn’t feel as real.

I will say, in the very beginning, when everybody was live streaming — musicians immediately took to those platforms — I was super inspired by that and by how quickly we can all adapt to “new norms.” I think it’s beautiful that our community feels so passionate about it that we found that outlet. And I’m so grateful that we have that outlet during this, but there’s nothing quite like being in a room with people and singing the songs. As far as my hope about it, I do have hope that this isn’t going to be the remainder of our lives, you know? I really do. If there’s anything I’ve learned by going through really dark, dark depressing moments is that right on the other side is usually the most beautiful moment. It really is.

How, if at all, has your mission in music changed or adapted in the past few months? Or has it been re-centered?

I feel like, if anything, it’s made my conviction for what I’ve always intended for my music truer. Since the very beginning I had many opportunities where I could’ve done this for different reasons, but I didn’t do them, because they weren’t what I felt my internal mission was. That internal mission has always been guided by connection — real, human connection. The very first shows I played where I was busking, if we got money that was a bonus. It was shocking, because to me it was more about, did somebody in the audience cry? Did I make somebody feel something? If anything, I’ve always been trying to get back to that. Especially in quarantine and COVID times. With everything that’s going on I feel even stronger about that conviction. And I feel silly for the moments where I’ve been afraid and done otherwise, in small ways.

I wanted to ask you about “If I Told.” One word can be so pivotal, that “if” changes the entire tenor of the song. And it’s almost a swallowed lyric, too. The song — which is about the telling not the if — is so expressive and does a great job of detailing the phenomenon of having something you simply HAVE to tell someone. it’s just festering, but you still don’t feel that you can. But, literally speaking, there shouldn’t be an “if!” Why is there an if? [Laughs]

When I was writing a lot of these songs, especially the ones where I had left the relationship and started dating again and was meeting people — “How You Get Hurt” and “If I Told” are both rooted in that — I kept saying, “Oh my god these are millennial love songs.” I think the reason that they are is the “if.” I would say this is a big difference between Boomers in the ‘60s and us, culturally. We are all afraid to say it. To just say it. We feel so much, so much, if not more than [these other generations]… but we are all so afraid! Afraid to connect with each other. We’re afraid of rejection. Or afraid of what might reflect in it, because we are so self-aware. Maybe it would hurt us too much? More than anything!

If I’m being completely honest, for me, personally, the problem was the lack of time. The lack of self-reflection. It was being catapulted from this nearly decade-long relationship with this person I essentially grew up with into these new, highly romantic situations. [It was] not having any time for me to rediscover who I was again. I’ve never been more ready to date in my life and to tell someone I love them than when I spent three months at home! [Laughs] With myself! Not drinking, not going out every night–

[Laughs] Every single one of us like, “Aw, shit I wish I didn’t want a boyfriend SO bad right now.”

I know! I know! [Laughs] Honestly, it’s because I’ve finally accepted myself! I think we all have problems, because we’re all so self-aware and have so much shame; there needs to be more conversation around imperfection because we’re all deeply flawed. We’re all human. It’s okay to forgive yourself and it’s okay to be wrong. Accepting those imperfections is something we all need to come to terms with. I think our culture, especially with social media, has a perfection problem.

Old Flowers, for all intents and purposes, was meant to be an intimate conversation. When I sang it, I wanted it to be that conversation you have where you aren’t blowing up at each other, threatening to jump out of the car. It’s the quiet conversation you have months later, when you’re catching up, and it’s delicate. You feel strange and disconnected, but still so close to this person you know so well. I think, in regards to my voice, on this record I was very intent on making it a quiet conversation, vocally.

I’ve always been such a big fan of performative singers, singers who perform as the character, as the person they’re singing about. Aretha did it, Joni does it, Billie Holiday did it, Linda Ronstadt does it, all of these great singers. I’ve always really been drawn to that. You don’t sing every word this straight, same way, you put care into every word. You sing with the story in you. If you don’t sing with the story inside you, then how can anyone relate to it?

All photos: Alexa Vicius