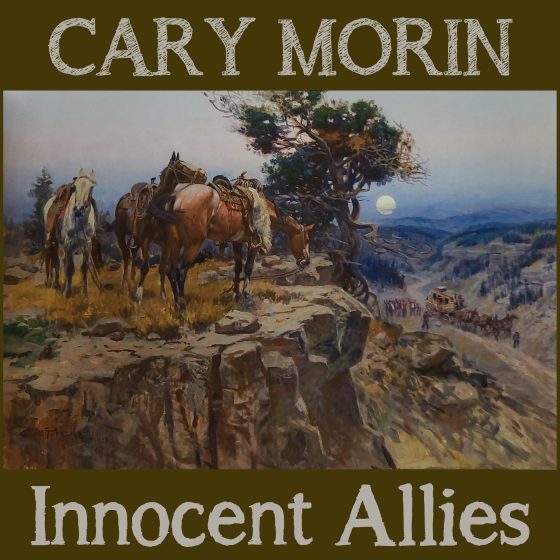

Guitarist Cary Morin’s (Crow/Assiniboine) new album, Innocent Allies, includes a striking painting on its cover created by renowned Western painter/sculptor Charles M. Russell (1864-1926), who spent his formative years as an artist in Morin’s home state, Montana. Innocent Allies, Russell’s work, depicts horses, cowboys, and settlers, routine subjects for the visual artist. The piece references how the iconic beasts of burden, who helped build the American West, were often innocent partakers in the violence, imperialism, and White Supremacy of American empire advancing across the rural, montane, wide expanses of the West.

For the new record, Morin leverages his expansive musical vocabulary – flatpicking, fingerstyle guitar, blues, folk, singer-songwriter, rock and roll and pop textures, and instrumental lyricism – to synthesize more than a dozen of Russell’s paintings and works into songs and tunes. The result is pastoral, evocative, and certainly cinematic. But these songs, as Russell’s body of work, are not sanitizations of the past or representations of American mythmaking and revisionism.

Morin views these paintings with a hefty dose of nostalgia, mentioning throughout our telephone conversation how this art was ubiquitous throughout his youth, his life in Montana, and its influence reaches well into his present, while he tours the country playing guitar from his new home base in Colorado. But that nostalgia isn’t predicated upon turning blind eyes to the atrocities endemic to Americana imaginations of “cowboys and indians,” Manifest Destiny, and the genocide and displacement of Native peoples.

Like Russell before him, Morin offers a grounded, realistic, and eyes-wide-open perspective not only on Russell’s body of work and those iconic images, but on the entire American societal construction of the West, as well. He does so with a formless and gorgeous genre fluidity and with playing styles entirely his own. Each track is stunning and expansive, even in their moments of intimacy and coziness.

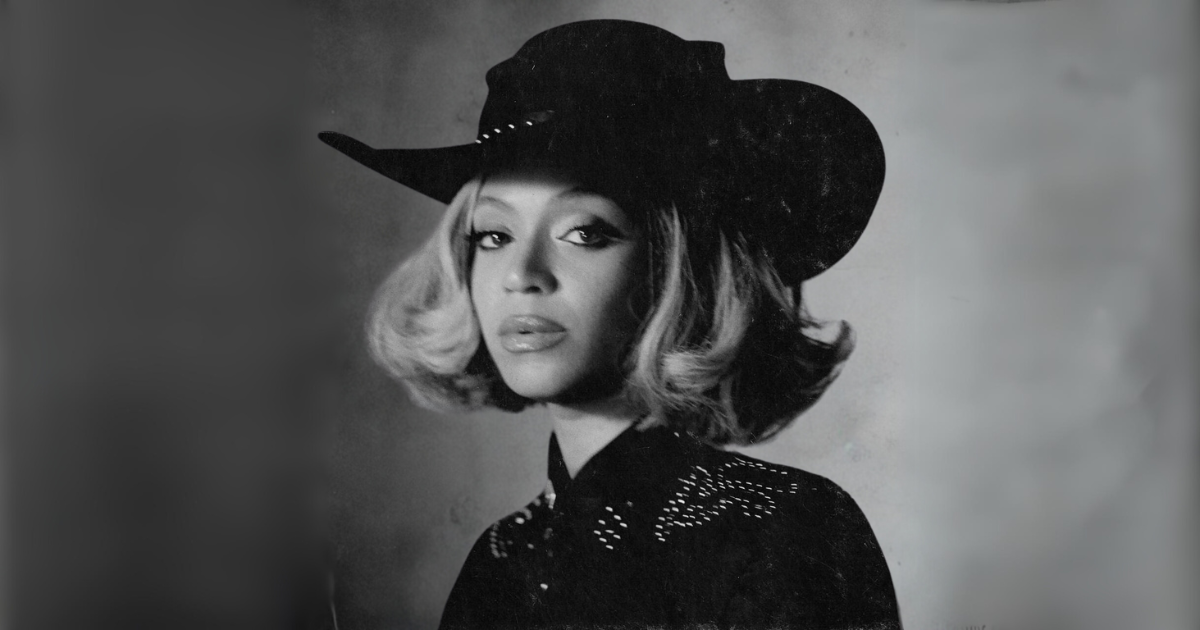

Innocent Allies is a delicious record, made ever more fascinating by its unique concept, its nuanced inspirations and influences, and Morin’s one-of-a-kind voice on guitar. We began our interview chatting about the album’s conception before discussing Montana bluegrass, the constructive uses of genre, Beyoncé’s impeccable choice in Rhiannon Giddens’ banjo playing, and so much more.

I wanted to begin by asking you about the art of Charles M. Russell and how it inspired the new album, Innocent Allies – not only is his work on the cover, but it’s also very clear that these are cinematic and very artful songs. They’re very evocative. How did you take a different medium than your own and translate it into your own art?

Cary Morin: The album and the artwork all comes from my upbringing in Montana in the ‘70s. People from Montana all know that Charlie Russell is our most famous artist that ever came out of Montana. There have been a bunch of [artists] actually, but he’s kind of the top of the pile. When I was a kid – probably even today, too – anywhere in the state, you’re gonna be surrounded by his paintings or his sculptures.

He moved from St. Louis, Missouri when he was, I think 16? His parents gave him a train ticket to go out [West] and they wanted him to work on a sheep ranch owned by a friend of theirs for a while to get this fascination that he had with Montana out of his system. But it kind of backfired. He ended up living out his days there, for the most part. He gradually became a really advanced sculptor and painter, eventually getting to the point where he could really [demonstrate] action in the things that he created. He could [depict] minute muscles and forces and accurate movement – same in his paintings.

He ended up doing thousands of paintings and sculptures. They’re in collections all over the world now. Not only in Montana, but there are some museums around the U.S. that have huge bodies of work from him. When I was a kid, the coffee table books that were soon to follow his work, my dad and my mom ended up having all of them. My dad was a huge fan of his books, his writing, his stories, the letters that he wrote to everybody, the paintings, the sculptures.

With that stuff just always laying around when I was a kid, I became pretty familiar with it. I’m by no means an expert at that, but I just grew up around it all and know it pretty well. With this album, originally I was going to do a tribute album. It was going to be as country as I could make it. I’m not really a country player, I grew up in Montana. I can understand how it’s put together, and I could play some pedal steel. I’m pretty much a novice, but I know enough to get by, at least in the studio. So, [originally], it was all going to be all written by another artist.

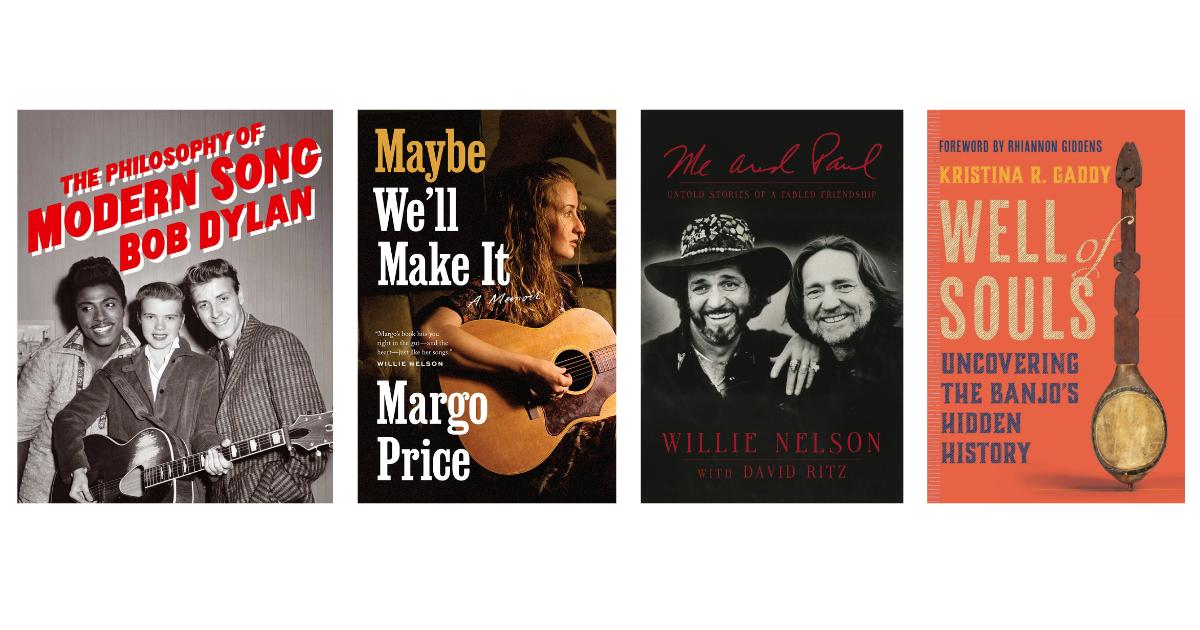

After a while, I just couldn’t get my head around putting out an album where I didn’t write a single song on it. I think we were at home listening to Red Headed Stranger and I thought, “Man, I really love the production on this.” That was another favorite of my dad’s. He loved Willie Nelson.

I thought the production feel of [that record] would go along with the paintings in the coffee table book that was sitting right in front of us. It was kind of like a moment and a suggestion. The more I thought about it, the more I was like, “This takes care of everything.” I know a fair bit about Charlie Russell and his paintings are so accurate, they all tell stories. So I just started writing stories about the paintings. Looking at them and trying to imagine that scene and that moment of time that he captured. I wondered what happened before that moment and maybe what happened after that moment. Pretty soon we had a good pile of songs. It was a really fun process. At the time, we didn’t know what we were going to do with it. I mean, maybe I felt like it was a good idea, but after if it ever got done, then what?

Well, it definitely sounds like your own kind of sculptural process to get to this album. Carving something and then seeing where it leads you; starting with an idea, but then following the art wherever it goes.

I want to ask you about genre, because we’re having this conversation in “the zeitgeist” right now with Beyoncé and with Lana Del Rey and other people “going country.” On one hand, genre feels so important in this moment and on the other hand, it feels like we are accelerating ever faster toward being in a post-genre world. When I listen to this album, like you’re saying, it does remind me of Red Headed Stranger. It is straight up and down country to me.

But I wonder how you view genre, yourself? Is identifying with genre useful to you? Do you think it’s kind of a vestige of the past? How do you identify with genre at this point and with this record?

Well, with me in particular, that’s a pretty interesting question, because in the early ‘70s, when I was starting to play music and get interested in music, I lived in Montana. With my dad being a military guy, I didn’t really have access to a lot of albums of a wide, eclectic variety of genres and of sounds. But I did end up listening to classical music and my folks were big country fans. My oldest brother was a rock fan. I would stumble across things. I became a bluegrass fan from the influence of my best friends.

I didn’t really understand genres. I just heard music and I liked it. I didn’t really know how to put labels on it. I wasn’t aware of publications that would outline where the boundaries are on music. I didn’t think of things as a specific genre – although, you know, I sure liked the way that Doug Kershaw played fiddle, however I came across that! Or, I really appreciated the way Chubby Checkers played piano. That was all from Louisiana, but I had no idea what Louisiana was, or what Canadian music was, or any of that. It was all just music that I liked.

Having grown up without all that knowledge, I think it did have an effect on how I play music, because I would kind of bounce from genre to genre. I played with a band for 20 years, and we would play like the way Stevie Ray Vaughan played blues guitar. I didn’t really understand that much about blues music, but I thought what he did on David Bowie’s album was amazing. And so that had an influence on the way I play guitar. I really love Pat Metheny, and that had an influence on how I play guitar. I really love Mark Knopfler. It’s like all these genres couldn’t be any farther apart, but they all had a place in my mind. I maybe didn’t realize it at the time, but all those little influences would end up having an effect on how I make albums.

Genres now, that I hear on the radio – which is really only when I drive around – that’s [usually] like a public station, a community radio station, so I don’t really hear pop music. But, everything’s kind of starting to sound the same. I don’t know why that is. I think that maybe money has something to do with it. You know, “What sells?” What the buying public listens to, in order for advertising to be sold. I guess I don’t really pay attention to it too much. But I think that a lot of it’s driven by money.

You know, I can’t understand why Beyoncé would shout out to the world, “I’m gonna face country music!” and have that feel [like a] benefit. I think that she would only do that if she was motivated by something other than her love of Hank Williams. [Laughs] You know what I mean?

[Laughs] it’s hard to imagine! And then, at the same time, in the 100-ish years country music has been around, this seems to be a routine move. There’s always this moment where the people on the inside aren’t making that much money, or feel like they aren’t making much money, and you see someone like Lana or Beyoncé coming and you think, “Wait… There’s money to be made here? What? Tell me more about this!!”

Exactly!

From listening to your music, I think I would describe you as “genre agnostic.”

But I was curious what your feeling was on the Beyoncé announcement and the press coming out on that.

I found it really interesting, because I’ve known Rhiannon [Giddens] for years. She played with Pura Fé an artist/group that I played with in Europe for like five years. To hear her pick up a fretless banjo and just beat it into submission, I was like, “Holy God!” I had never heard anybody play a fretless banjo before, let alone like that. What a perfect choice for Beyoncé. She picked one of the best banjo players that I’ve ever met. I was surprised and impressed.

Yeah, me too. And also to have Robert Randolph playing steel on the tracks. Beyoncé and her team very clearly knew that she couldn’t appear like a “carpetbagger.” It’s not the most perfect term in this context, you know what I mean. She didn’t want to be viewed as somebody who was interloping – she did a good job at that “authenticity signaling” for sure.

It’s a wild thing to watch happen and to watch the discourse, in the wake of the two tracks, half of the people being like, “That’s not country” and half of the people being like, “Black folks invented country music, Indigenous folks invented country music, this is nothing new.” To watch those factions bump up against each other again, it’s kind of endlessly fascinating to me.

Like John Travolta having a hand in the revival of Texas music! Some idea that somebody somewhere along the line has and it catches on and takes off. I like it, too. I think culturally, I love it when things evolve. I do remember when I was a kid that I would hear on the radio what people call “country music” and go, “Boy, isn’t this happening in what is called Southern rock already?” There’s always players borrowing from other players.

And then it’s the studio musicians that played in that stuff. They may have showed up on a Bob Marley album somewhere along the line, too, because they played in a studio. Hell, man, when I was a kid I didn’t even know who Bob Marley was. I think it’s great that people learn from each other.

I wanted to ask you about bluegrass. You talked a little bit about what bluegrass means to you earlier in our conversation, but also when we premiered your track, “Whiskey Before Breakfast,” but I wanted to give you a chance to talk about your bluegrass influence again – we are the Bluegrass Situation, after all. What does bluegrass mean to you as a genre, as a picker?

That also goes back to the ‘70s. When I was talking about all the music that I either got from my family or from older brothers and my best buddies – bluegrass was a pretty big deal in Montana back in those days. I remember early on listening to these albums that didn’t exist in my friends’ houses. Hearing about Flatt & Scruggs and maybe I heard it on TV. I’d see things on Hee Haw

And it definitely piqued my interest.

But the stuff that was going on in Montana, there was a band called Live Wire String Choir, which was a Montana bluegrass band. There was another one called Lost Highway Band that was a little bit electrified, but still bluegrass. And then there was the Mission Mountain Wood Band, which was kind of the king of all of them. They were straight ahead bluegrass, but from around Missoula. They actually appeared on Hee Haw one time, although I never saw that episode. They had an album called In Without Knocking back in the day and I was maybe around 12 years old, something like that. Everybody was buying that album. We had a copy of it, so I was learning those songs.

I think there was a plane accident and a lot of the band didn’t survive, but there’s one guy, his name is Rob Quist, who was one of the founders of the band. He still plays shows in Montana. His music and that band’s music turned me on to bluegrass. Through investigation and through the help of friends, I learned more and more about it. I got way into flatpicking. I never had an American-made guitar when I was a kid. I didn’t really realize the importance of that.

I was still fascinated with Tony Rice, and still fascinated with the crazy melodies that David Bromberg pumped out. I love John Hartford – so it was, I guess, a personal quest of mine. I have some friends that are pretty good bluegrass players. But I left Montana when I was 18 and I kind of pursued bluegrass for a while, but then I kind of got back into fingerpicking and fingerstyle guitar and eventually electric guitar.

And all that Clarence White stuff that I had heard and the Will the Circle Be Unbroken album, a lot of those artists that were kind of starting to press the boundaries of bluegrass music caught my attention. Eventually, I just abandoned that piece of guitar [playing] altogether and got really into playing electric guitar for many years. It wasn’t until maybe 20 years ago that I started really getting back into playing acoustic guitar. I never really abandoned electric, but I started playing fingerstyle guitar and pursuing it. I’d play for five, ten hours a day, daily. I just couldn’t get it out of my mind, largely thanks to Kelly Joe Phelps.

The early acoustic experiences that I had never really went away and I was really interested in creating music based on all of those influences throughout my life.That’s where the fingerstyle thing came back in.

I think the tune that I like the best on the album is “Bullhead Lodge.” And I love the Charles Russell painting that inspired it. I wondered if you could take us into your composition process for “Bowhead Lodge” and specifically, how you were synthesizing those related paintings while you were improvising, composing the tune – because I think that’s really fascinating.

Well, thank you. I’m glad that that song resonates with you. First of all, Charlie’s painting of his cabin on Lake McDonald – Charlie painted from memory, he’s not a guy that you would see sitting out in the middle of the fields with an easel, as romantic as that looks, he wasn’t that guy. He ended up painting a lot of depictions of his view of the lake from Bullhead Lodge. There are so many of them and they’re all just serene.

I was playing a show with Phil Cook in North Carolina and at sound check, he said, “Cary, we could just play this thing…” and he played this short, open-tuning melody. “We could play this thing for 10 minutes and people would love it,” he said.

We just kind of sat there and tweaked it for a little while. I don’t remember the melody he played. We didn’t do that during the show. But, I always remember him saying, “Play the simple thing and people will love it.” When I was looking at those paintings of Lake McDonald, I just started playing this melody. It wasn’t really written on the spot, I suppose. I goofed around with it for a couple of hours, but then I came up with sort of four variations of a similar melody. I started with a simple one and then changed it and changed it and changed it until the chords finally changed into what tags the song.

Because of that process, I like that song too, because it’s a great memory. I was glad that it made it onto the album. People have been talking about that recording, it seems like it’s resonated with folks.

Photo Credit: Grayson Reed