At your average live music event on the folk and bluegrass circuit, the stage isn’t the only place where great performances are happening. There’s the campfire and parking lot picking scene at the big outdoor festivals, of course. But a lot of it goes on out of sight backstage, too, when musicians who don’t often see each other come together to play with and for each other. A close approximation to listening in on that is Mighty Poplar (Free Dirt Records), the self-titled first album by the group of the same name.

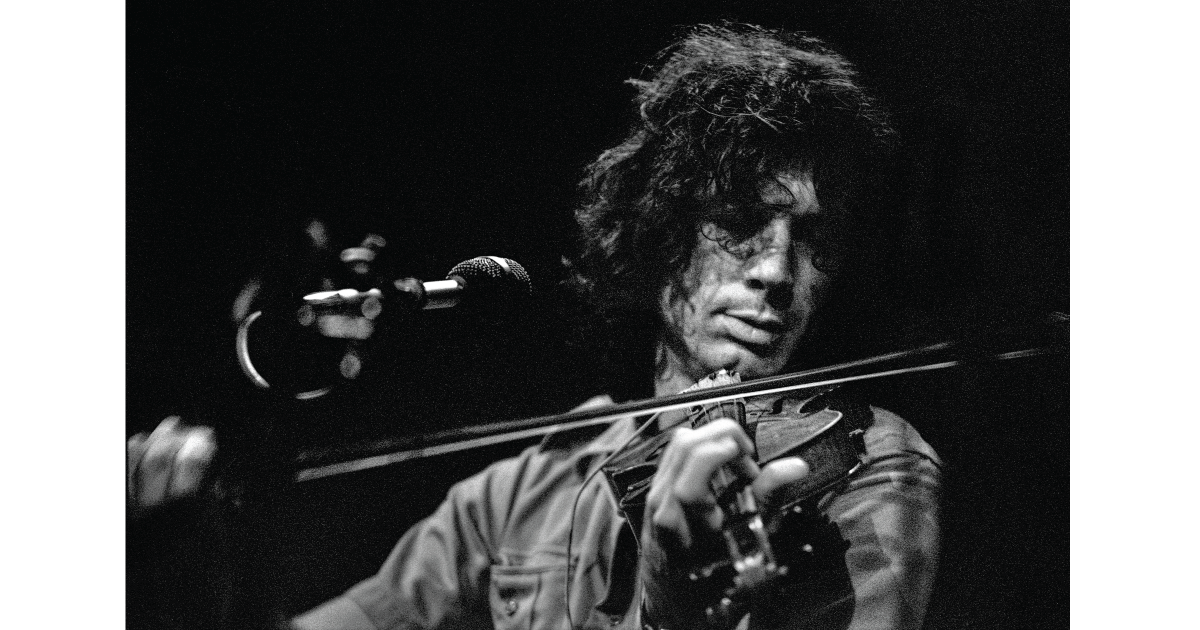

The bluegrass world’s newest supergroup, Mighty Poplar is a five-piece band centered around three virtuoso players from the Punch Brothers orbit — banjo player Noam Pikelny, guitarist Chris “Critter” Eldridge and original Punch Brothers bassist Greg Garrison, currently in the band Leftover Salmon. Out front as primary vocalist is Watchhouse mandolinist Andrew Marlin, with well-traveled fiddler Alex Hargreaves (currently knocking ’em dead in Billy Strings’ touring band) filling out the lineup. Over the years, various subsets of this quintet would cross paths out on the road and jam, generally falling back on the old numbers everyone knew as a common language. That’s how Mighty Poplar began to coalesce.

“There’s a pretty complex web of relationships between all five of us that began with a lot of hanging out,” says Pikelny. “There’s this beautiful thing about bluegrass, the amazing music and all the shared songs. There’s a great social component that can exist with the music if you let it, and it became a reason to get together and have fun.”

While none of Mighty Poplar’s members come from acts you’d really call “bluegrass,” you could say they’re all at least bluegrass-adjacent. And none of them have ever come down as top-dead-center old-school bluegrass as on Mighty Poplar. The album’s 10-song tracklist draws material from A.P. Carter, Bob Dylan, John Hartford and Leonard Cohen, with songs made famous by the likes of Hazel & Alice, Uncle Dave Macon and Bill Monroe fiddler Kenny Baker.

Monroe, the Father of Bluegrass, also figures into the proceedings in terms of inspiration for the ensemble’s name. Proposing Mighty Poplar as a moniker was Marlin, someone who definitely knows his way around names involving wordplay (witness the original name of Watchhouse: Mandolin Orange).

“I was listening to a Bill Monroe and Doc Watson live recording where they were about to kick off ‘What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul?’” Marlin recalls. “Bill said he and Charlie recorded it in ’19-and-36’ in Charlotte and it had been ‘mighty poplar down through the Carolinas.’ We had a huge text thread already going about band names, where my phone was always going BING at 2:30 a.m. So many names we considered, but everybody thought Mighty Poplar was a good awning to stand under.”

While Mighty Poplar is only now coming out in the spring of 2023, the album has actually been in the can for a couple of years. It might never have happened without the Coronavirus pandemic shutdown of 2020-21, which took everyone’s regular bands off the road for an extended period of time.

In isolation, everyone felt drawn toward bluegrass as the musical equivalent of comfort food. So they took this on as a pandemic project, convening with engineer Sean Sullivan at Nashville’s Tractor Shed for a brisk three-day session in October of 2020.

“There was a sense that we were getting away with murder, traveling across the country and podding up while everything was closed up,” says Pikelny. “There were logistical hurdles and we had three days, so we had one shot to get it all at once. So we worked out as much as we could ahead of time, even the sequence. The concept, if there was one, was that this was the closest thing to a real-deal, traditional, classic bluegrass project any of us have done in a long time, maybe ever.”

As lead vocalist on six of the album’s 10 songs, Marlin is the primary out-front voice of Mighty Poplar. But he felt like he had to step up his game on the instrumental side, to keep up with his bandmates.

“It was intimidating, but not because those guys are intimidating,” Marlin says. “As a musician, I’ve had to figure out how to feel like I can express myself in front of people I look up to. But that’s on me for projecting my own shit onto them, because they don’t wear that. So ‘Grey Eagle,’ an instrumental fiddle tune Alex brought forth, I was kind of sweating that one in the studio. That kicked off at 150 beats per minute and everybody else is just looking around, casually exploring the nooks and crannies of the tempo while I’m popping a vein and kind of being drug behind the horse. But I managed to keep it together. Ultimately all those guys still love a great song as much as anyone. There’s something about simple songs that leave it up to the player to bring whatever they want. I love it when the song’s not telling you how to play it, and I feel lucky that they were down to explore that approach.”

Song choice was pretty casual, mostly in favor of material from a bit off the beaten path. Even with a Hall of Fame list of songwriters, they focused on less-well-known songs from the repertoire of each — Dylan’s take on the A.P. Carter tune “Blackjack Davy” rather than “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” or Hartford’s Mark Twang riverboat song “Let Him Go On Mama” rather than “Gentle On My Mind.”

“It all happened pretty organically,” says Eldridge. “In the initial text volley about what to do, there were a lot of songs we would’ve been happy to cut. It’s hard to say why we landed on these particular songs other than that they felt right. I would not say there was an overarching concept beyond good songs that felt right.”

While they considered including some originals, ultimately they decided to stick with covers, mostly of older vintage (the most recent song on it is Montana singer/songwriter Martha Scanlan’s “Up on the Divide,” from 2012). In that way, Pikelny looks at Mighty Poplar as a classic folk record.

“In other genres, people might call this a ‘covers album,’” says Pikelny. “But if you record solo Bach compositions, that’s not ‘Bach covers.’ It’s repertoire, reinterpretations of classics to pass down. It was born of a desire, almost a need for all of us, to gather around a bluegrass project. And it was such a joyous process. It felt like coming home for Thanksgiving or Christmas and being around family you’ve not seen in a while, in the home you grew up in with a turkey in the oven. It was that kind of comfort, the warm fuzzy feelings of gatherings like that.”

It went so well, in fact, that they were in no hurry to get around to the detail work of mixing and mastering the record after they finished tracking. Pikelny says they felt almost paranoid about not wanting to touch it, for fear of messing up a good thing.

“We’ve been sitting on this for so long because it felt like such a special session,” Eldridge says. “So effortless and deeply joyful. Magical, even. We didn’t want to let it go because it felt like all we could do was ruin it. But I kept coming back to it, listening now and then and thinking, ‘I really like this. We have to share it, plus it’s a good excuse for us to get together again.’ It’s ironic that we’ve not actually played it live yet, and we’re already kind of getting the next batch together.”

Indeed, Mighty Poplar’s first real touring commences in May. With Hargreaves busy playing arena-sized venues with Strings for the foreseeable future, John Mailander will stand in for him on the first leg of touring. And all the principles are cautiously optimistic that Mighty Poplar’s first album won’t be its last. Pikelny likens their hoped-for trajectory to Tony Rice and J.D. Crowe’s Bluegrass Album Band, which periodically convened to make albums and tours through the 1980s and into the ’90s.

“Bluegrass Album Band was never a full-time group for any of those guys, it was a very sustainable side project whose records served as homecomings,” says Pikelny. “They’d go off to do whatever else and then come back for another edition. It’s a celebration of our love for bluegrass. As long as it stays as effortless as this felt, I think we’ll keep doing it when we can.”

Photo Credit: Brian Carroll