No BGS reader needs a rundown of Tony Rice’s biography or accomplishments. Earlier this month I chatted with Todd Phillips, Tony’s close friend and bassist across multiple groups (David Grisman Quintet, Bluegrass Album Band, Tony Rice Unit) from 1975 to 1985. During these years Tony used inspiration from mid-century jazz and musical peers, along with his innate willpower, as levers to crack open a stunning new guitar vocabulary. In doing so he rose from a bluegrass badass to a global force, operating well above tribes and vogues.

When Todd emerged in the 1970s, bass guitar was a cross-genre norm. A young upright player who melded Scott LaFaro’s gracefulness with J.D. Crowe’s timefeel was a fairly wonderful anomaly in bluegrass. I started working with Todd in 2014, and grew close with him fast. He brought something rare — a relaxed whiphand — to the feel onstage. In the van, he indulged my ceaseless fanboy questions about the old days. An equable ex-stoner with a mildly grumpy edge, he’s as adept at building an instrument or a chicken coop as analyzing acoustic riddles, and his long experience working with people as unalike as Joan Baez, David Grier, and Elvis Costello gives him a high perch from which to reflect. He reminisced fluidly about Tony over the phone with me for two hours, stopping only twice, once overwhelmed by emotion and once to get a bottle of tequila. (Read more from our conversation at my blog.)

Robbie Fulks: I listened back today to California Autumn and other records I hadn’t heard for ages, and heard little passages that sounded uncharacteristic of Tony. Did gestures come into his vocabulary, stay there for a while, and then fade off as he went to concentrate on another idea?

Todd Phillips: That’s true, yeah. He would go through cycles, get on a kick. He’d get on riffs, like hearing Billy Crystal: “You look marvelous.” He’d say that 40 times a day, and a year later, drop it for some other riff. The vocabulary would change, according to the era.

That’s fascinating, to compare it to a non-musical example. So let’s dive in, go back to the start. Tell me about meeting Tony — when, where, and how you guys got underway with the Grisman project.

I was a beginning mandolin player, and I was certainly in over my head, playing mandolin with David, but he’d never heard me play bass, which I’d played since I was a little kid. This was 1974, and Clarence White had died the year before. And we just thought, this is a good band, we don’t need a guitar — no one else could fill Clarence’s shoes, and he’d be the only guy that would work in this thing. Then David came home from a Bill Keith recording session and said, “I just met the guy that could do it.”

Shortly after that, J.D. Crowe and the New South were on their way to Japan, and they stopped in San Francisco to play one gig. They hung with us for a couple days and… I had never hung with, um, that many guys from Kentucky all at once. [Laughs]

I’ve told you about that Mexican restaurant in Berkeley. The Californians — me, Darol, and David — and the Kentucky guys — J.D., Tony, Ricky, Jerry, and Bobby — were seated at one giant round table. First, Crowe ordered: “Six tacos and a Coke!” Then each New South guy ordered exactly the same. I guess they were used to the little three-inch tacos you can eat in two bites. So this big table ended up covered with plates full of giant tacos, surrounded by a pretty interesting mix of characters. I wish we had a photo. Polyester and tie-dye T-shirts all around.

After they came back from Japan, Tony gave J.D. his notice. He hooked up a little U-Haul trailer — clothes, suitcase, guitar, and stereo system — and got an apartment in Marin County. And we started rehearsing. At that point, we had what we had, but then Tony’s chemistry came into it. And it just catalyzed the whole thing. It was huge. Tony had to learn his harmony and a bunch of chords he hadn’t really played before — but we had to learn to play rhythm like J.D. Crowe. So we probably rehearsed for another six months before we went out and played our first shows.

Tell me about the first gig.

Our first show was in Bolinas [in Marin County], in the community center. We made our own posters and put them up all over Bolinas, so it was sold out. And no sound system. We wanted people to hear us just like we rehearsed. There were probably 200 people there.

So small room, gather round, and somehow the guitar projected through.

We played with dynamics — if Tony was soloing, we shut ourselves up. We got down light and tight under him. Since we hadn’t played through a sound system, we just did what we did every day anyway.

The first on-the-road thing, not long after, was in Japan. Our show was a bluegrass quintet with Bill Keith and Richard Greene, followed by a set of DGQ. Then, as soon as we got back from Japan, we recorded the first quintet record. So it still had that energy. We were still excited to hear it, too, every time — it would raise the hair on our arms! It was kind of a… strong existence. Life felt — pumped up, you know?

Close companions in an intense situation. A lot of people have been in a band or in the army. But on top of that, you guys were altering the course of music.

Yeah. Maybe it is a little like an army buddy. I was a cross between his bass player and his little brother. Also his babysitter, sometimes! He had left his old friends, and when he came to California, I seemed to be the guy he gravitated to. On off days, all of a sudden there’s a knock on the door at 10 a.m., and it’s Tony — “Hey man, let’s go the boardwalk, ride the roller coaster. Let’s go to the record store.” We went to the record store a million times. Came home with bags of records and stayed up all night listening — I mean, he taught me to listen close, whether playing music or just listening to records.

Any memories of the 1975 Grisman Rounder album sessions?

Tony was hilarious! We’d go out to eat, and he’d come back with a couple of cloth napkins. He’d fold one up and put it on his head, and put on sunglasses. Looking like a weird Quaker. And then drape another napkin over his left hand and go, “I don’t want anybody to steal any of my licks.” [Laughs] He’d leave that thing on his head, with the sunglasses, for like, three hours.

Have you heard guitarists who managed not to sound like Tony, in the years since?

Well, because Tony opened the door, after Clarence, you can’t help but sound like him as a bluegrass soloist. He found those avenues on a fingerboard that you can play with a strong attack and accurate, strong expression. A lot of it is mechanics. A D-28 with semi-high action, there are certain phrases that fall naturally under your fingers, and Tony found those. So I think a lot of guitarists use those avenues because — they’re there. You might hear different phrases but they’re not as strong. They might be more interesting, or more academically pleasing, but the effect — I haven’t heard it as strong as in those passages that Tony found.

Tell me about Manzanita.

There was no preparation that I remember. The guys came to Berkeley and we went to work. We ran a tune for 20 minutes, then recorded it maybe three to six times.

Béla Fleck said Tony didn’t like to rehearse much.

Yeah. Sink or swim.

Any road memories involving Tony?

He didn’t go out a lot. We went to Japan once, the three Rice brothers — Larry, Wyatt, Tony — and me. And Tony — maybe that’s when he started — he just never left his hotel room.

What was he doing in there?

Ordering room service. Later, traveling with the Unit, he’d stick to the room. I mean…he pretty much lived in front of his stereo, smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee. That’s what he thrived on.

How did you listen to music away from the home stereo back then?

In the early days, he drove a noisy Dodge Challenger. A muscle car, with a cassette player in the dashboard. We’d listen loud. And driving from Grisman’s house back to mine every night, it was pretty much all John Coltrane, the classic quartet.

Interesting!

Yeah, and later, a lot of Oscar Peterson. He’s like Tony: you recognize the phrases, and they’re strong as hell. Meticulous mechanics. Tony never studied music academically — but the sound of it. He took that in and it’d come out later somehow, the power and the attitude, more than specific notes or theory.

Did he have any relationship to the written page?

No. Not at all.

Tony cited Miles Davis and Eric Dolphy as favorites, but I don’t hear a strong kinship.

I think those were unique voices. Like Django, or Vassar.

Individualists.

I think that’s it. The attitude. He liked those kind of characters, like David Janssen — he really had an obsession with David Janssen. Or Lee Marvin.

Ha!

I’m not kidding! The Marlboro Man.

People that laid it down.

Exactly.

I’m curious about the chemistry between Tony and other strong personalities. You’ve told me your take on the Skaggs-Rice dichotomy, the good and bad guys from everyone’s high school…

Yeah, Ricky would be class president and Tony would be Eddie Haskell. [Laughs] There’s a little of that, but musical respect bridges all gaps.

With David, did Tony slip easily into a sideman role?

The chemistry was — not volatile, but exciting. The New Jersey hippie and Mister Perfection. You know, when Tony was new to California, David’s living room was a real event. You never knew who you’d run into — Jethro Burns, Taj Mahal, Jerry Garcia. I think that excited Tony. He’d dig in his heels, just be who he is, and people respected that. He was…I guess I want to use the word “stubborn.” Clear-headed, with his vision.

Were cigarettes it for Tony, or were there harder things he liked to do?

No! He actually went light on the marijuana, compared to everyone else in Marin. He kinda puffed a little bit, just to participate.

Any whiskey?

No, he drank a few beers at home. I don’t remember any hard liquor at all.

I read in The Guardian obit: “apprentice pipe fitter”…?!

Yeah! His dad was a welder, pipe fitter, and Tony and his brothers did that too.

What did he do to keep his fingers strong besides play?

Nothing. He bit his nails. He had no fingernails, and his fingertips looked like blocks of wood. Like the rounded end of a wooden dowel. The guy played a lot. He had hands that physically, mechanically, work in a different way. He could push down with his thumb, on his right hand, but also push up, with his first finger. You can look at YouTube and see it — a really strong muscular mechanism between thumb and index.

His down and upstrokes weren’t ascribed to the usual beats, weren’t automatized in the normal way — and were equally forceful.

Yeah. And rhythmically, a lot of triplet syncopation on the upstrokes. People just say “syncopation,” but technically it’s playing 3/4 against 4/4, like Elvin Jones’s drumming. You can’t tell if it’s in 3 or 6 or 4 or 2. It’s all of it. It’s all of it! And those subdivisions, I learned that from Tony — you slice that up in all kinds of ways, so those polyrhythms are all churning in your hands or head at the same time. That’s what generates good time, not tapping your foot. Tony had all those superimposed polyrhythms in him.

Bluegrassers work hard and live long, on the whole. And with so many players of your generation now in their 70s and performing as energetically as ever, Tony’s story looks more profoundly sad to me.

You know, I don’t know why Tony went the way he went. Why he couldn’t be as youthful as Sam Bush. Who knows, if there was some kind of a depression, or if that desire for perfection wore him out. You know? Because he did play with joy, but it was also that crazy obsession, to be perfect and accurate — maybe he was just too hard on himself.

He was hard on everybody around him. I know that I developed way more than I ever would have developed if I’d never known him. It was not that he was ever mean or harsh to me, but being around him, you put pressure on yourself to live up. I think everybody that played with him was like that. He jacked up the music to this level — and then it was your challenge to get up there with him. Being around him changed me forever.

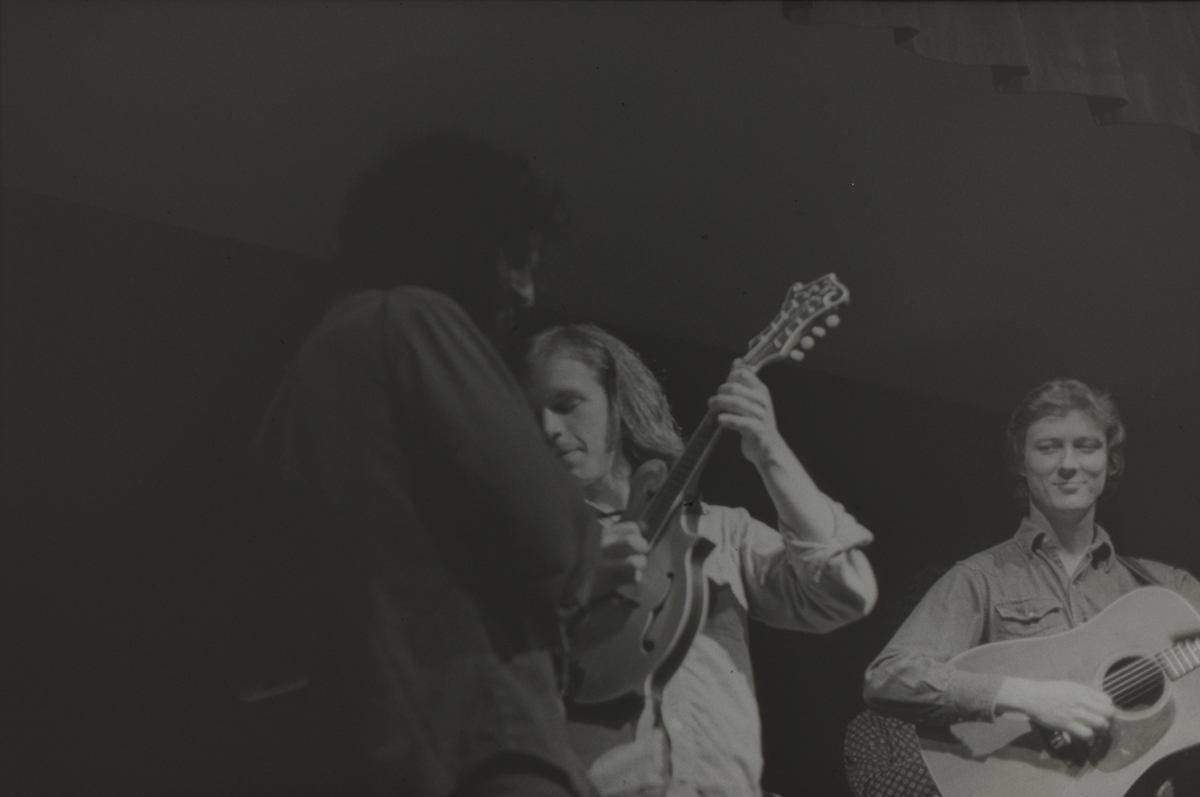

Lede image by Heather Hafleigh. All photos provided by Todd Phillips and used by permission.